Automate the deployment of Docker containers on arbitrary infrastructure

Containerization of applications today is not just a fashion trend. Objectively, this approach allows to optimize the server development process in many ways by unifying the supported infrastructures (dev, test, staging, production). As a result, this leads to a significant reduction in costs throughout the life cycle of the server application.

Although most of Docker’s enumerated merits are true, those who in practice will encounter containers may suffer slight disappointment. And since Docker is not a panacea, but is only included in the list of “medicines” from the automatic deployment recipe, developers have to master additional technologies, write additional code, etc.

We have been developing our own recipe for automating the configuration and deployment of containers to various infrastructures in the past few months, in parallel with commercial projects. And the obtained result almost completely satisfied our current needs for auto-warm.

')

Tool selection

When for the first time there is a need for automatic Deploying Docker applications, the first thing that prompts experience (or a search engine) is to try to adapt Docker Compose for this task. Initially conceived as a tool to quickly launch containers on the test infrastructure, Docker Compose, however, can also be used in combat . Another option that we considered as a suitable tool is Ansible , which incorporates modules for working with Docker containers and images .

But neither one nor the other solution did not suit us as developers. And the main reason for this lies in the way the configurations are described - with the help of YAML files. In order to understand this reason, I will ask a simple question: do any of you know how to program in YAML? I am surprised if someone answers in the affirmative. Hence, the main drawback of all the tools that use all sorts of markup to configure (from INI / XML / JSON / YAML to more exotic ones, like HCL ) is the impossibility of extending the logic in standard ways. Among the shortcomings can be mentioned the lack of autocomplete and the ability to read the source code of the function used, the lack of prompts about the type and number of arguments and other pleasures of using the IDE.

Next, we looked towards Fabric and Capistrano . For configuration, they use the usual programming language (Python and Ruby, respectively), that is, they allow to write custom logic inside configuration files with the possibility of using external modules, which we, in fact, wanted. We did not long choose between Fabric and Capistrano and almost immediately stopped at the first. Our choice, first of all, was due to the presence of expertise in Python and its almost complete absence in Ruby. Plus, confused by the rather complicated structure of the project Capistrano .

In general, the choice fell on the Fabric. Due to its simplicity, convenience, compactness and modularity, he settled in each of our projects, allowing you to store the application itself and the logic of its deployment in a single repository.

Our first experience of writing a config for automatic deployment using Fabric made it possible to perform basic actions on updating the application on the combat and test infrastructures and allowed us to save a significant amount of developer time (we don’t have a separate release manager). But at the same time, the settings file was rather cumbersome and difficult to transfer to other projects. We thought about how the task of adapting configs for another project is easier and faster to solve. Ideally, I wanted to get a universal and compact deployment configuration template on a standard set of available infrastructures (test, staging, production). For example, now our configs for auto-heating look like this:

fabfile.py

from fabric import colors, api as fab from fabricio import tasks, docker ############################################################################## # infrastructures ############################################################################## @tasks.infrastructure def STAGING(): fab.env.update( roledefs={ 'nginx': ['devops@staging.example.com'], }, ) @tasks.infrastructure(color=colors.red) def PRODUCTION(): fab.env.update( roledefs={ 'nginx': ['devops@example.com'], }, ) ############################################################################## # containers ############################################################################## class NginxContainer(docker.Container): image = docker.Image('nginx') ports = '80:80' ############################################################################## # tasks ############################################################################## nginx = tasks.DockerTasks( container=NginxContainer('nginx'), roles=['nginx'], ) The given code example contains a description of several standard actions for managing a container in which the well-known web server is launched. Here is what we will see by asking Fabric to list the commands from the directory with this file:

fab --list

Available commands:

PRODUCTION

STAGING

nginx deploy [: force = no, tag = None, migrate = yes, backup = yes] - backup -> pull -> migrate -> update

nginx.deploy deploy [: force = no, tag = None, migrate = yes, backup = yes] - backup -> pull -> migrate -> update

nginx.pull pull [: tag = None] - pull Docker image from registry

nginx.revert revert - revert Docker container to previous version

nginx.rollback rollback [: migrate_back = yes] - migrate_back -> revert

nginx.update update [: force = no, tag = None] - recreate Docker container

Here it is worth explaining a little that, apart from typical deploy, pull, update, etc., the list also contains the PRODUCTION and STAGING tasks, which do not perform any actions at startup, but prepare the environment for working with the selected infrastructure. Without them, most of the other tasks cannot be performed. This is a “standard” workaround of the fact that Fabric does not support an explicit choice of infrastructure for work. Therefore, in order to start the process of deploying / updating a container from Nginx, for example, to STAGING, you need to run the following command:

fab STAGING nginx As it was easy to guess, almost all the “magic” is hidden behind these lines:

nginx = tasks.DockerTasks( container=NginxContainer('nginx'), roles=['nginx'], ) Ciao, Fabricio!

In general, let me introduce Fabricio , a module that extends the standard features of Fabric by adding functionality for working with Docker containers. The development of Fabricio allowed us to stop thinking about the complexity of implementing automatic deployment and to concentrate entirely on solving business problems.

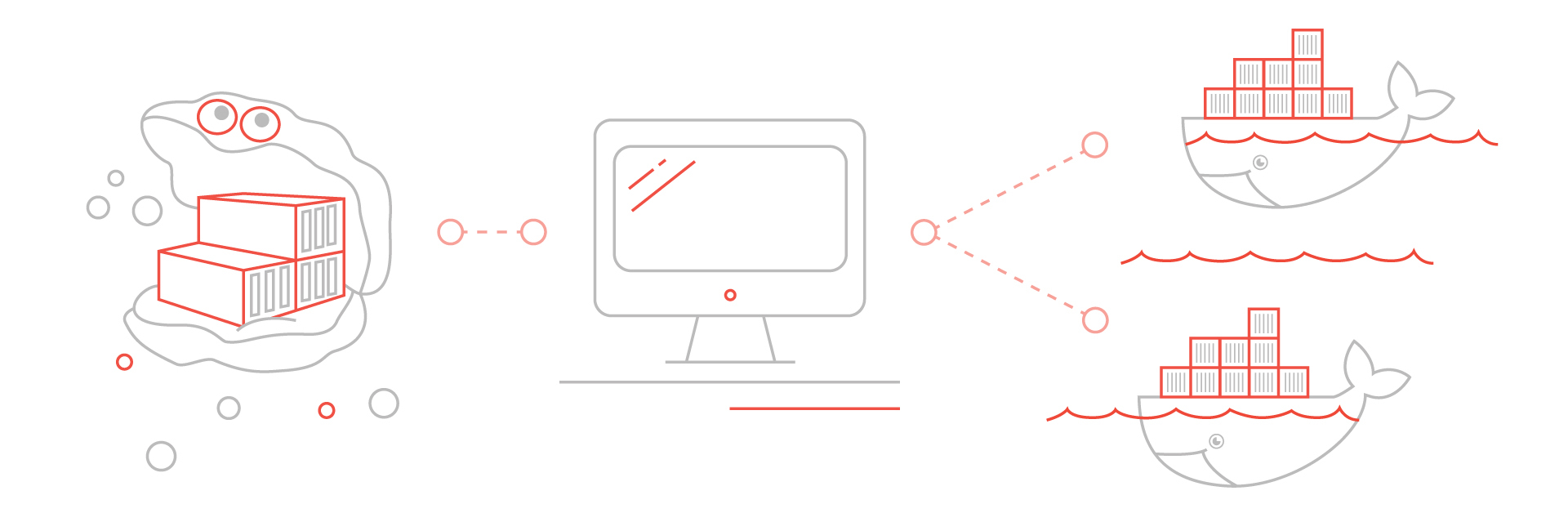

Very often, we are faced with a situation where there are restrictions on access to the Internet on the combat infrastructure of a customer. In this case, we solve the deployment problem with the help of a private Docker Registry running on the administrator’s local network (or just on his work computer). To do this, in the example above, you only need to replace the type of task - DockerTasks with PullDockerTasks . The list of available commands in this case will take the form:

fab --list

Available commands:

PRODUCTION

STAGING

nginx deploy [: force = no, tag = None, migrate = yes, backup = yes] - prepare -> push -> backup -> pull -> migrate -> update

nginx.deploy deploy [: force = no, tag = None, migrate = yes, backup = yes] - prepare -> push -> backup -> pull -> migrate -> update

nginx.prepare prepare [: tag = None] - prepare Docker image

nginx.pull pull [: tag = None] - pull Docker image from registry

nginx.push push [: tag = None] - push Docker image to registry

nginx.revert revert - revert Docker container to previous version

nginx.rollback rollback [: migrate_back = yes] - migrate_back -> revert

nginx.update update [: force = no, tag = None] - recreate Docker container

New prepare and push commands prepare an image from the main Registry and download it to the local one, from where the image gets to the combat infrastructure (through the pull command) through the tunnel . You can start the private Registry locally by running the following line of code in the terminal:

docker run --name registry --publish 5000:5000 --detach --restart always registry:2 The example with the assembly of the image differs from the first two, similarly, only by the type of task - in this case it is BuildDockerTasks . The list of commands for tasks with an assembly is the same as in the previous example, except that the prepare command instead of downloading an image from the main Registry builds it from local sources.

To use PullDockerTasks and BuildDockerTasks, you need a Docker client installed on the administrator's computer. After the announcement of Docker public beta versions for MacOS and Windows platforms, this is not such a headache for users.

Fabricio is a completely open project, any improvements are welcome. At the same time, we ourselves are actively continuing to supplement it with new features, correct bugs and eliminate inaccuracies, constantly improving the tools we need. Currently, the main features of Fabricio are:

- Docker image build

- launch containers from images with arbitrary tags

- compatibility with parallel execution of tasks on different hosts

- the ability to roll back to the previous state (rollback)

- working with public and private Docker Registry

- grouping of typical tasks into separate classes

- automatic application and rollback of Django application migrations

Fabricio can be installed and tried via standard Python package manager:

pip install --upgrade fabricio Support for now is limited to Python 2.5-2.7. This limitation is a direct consequence of the support of the corresponding versions of the Fabric module. We hope that in the near future, Fabric will acquire the ability to run on Python 3. Although there is no need for this special one - in most Linux distributions, as well as MacOS, version 2 is the default version of Python.

I would be happy to answer in the comments on any questions, as well as listen to constructive criticism.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/303118/

All Articles