Count the invisible: reliably determine vocabulary

At Skyeng, we rarely teach English from scratch. Usually people come to us who already have some kind of knowledge, and this set is very different. In order for the training to be useful, we need to somehow define the boundary of this knowledge. If in the case of grammar it is relatively simple (it turns out at the first lessons with a methodologist), then clarifying the boundaries of vocabulary is not a trivial task. To solve it, we developed and launched the WordMash tool.

Word ordering

Memorizing words is one of the main components of learning a foreign language, which spends most of the time and effort of a student. However, the words of any language, including English, are not equivalent: some are more useful, because more common (walk vs perambulate); some easier to memorize (process vs outgrowth), with some student constantly deals with work or by virtue of interests. To build the most effective curriculum (giving a tangible result in the shortest possible time) it is necessary to consider these factors.

To effectively learn new words and keep old ones in memory, it is important to be able to identify a student’s vocabulary (lexicon). The traditional approach is to intuitively determine the volume of a lexicon by a teacher on the basis of communication and tests. Such an approach, however, is fully based on the experience and qualifications of the teacher and cannot be objectively controlled.

The ideal method for determining all words known to a student would be a questionnaire for the entire dictionary of a language with two possible answers - “I know” and “I don't know.” It is clear that it is practically impossible to implement such a method: few students are willing to spend several weeks continuously answering questions.

Therefore, a well-established method, based on the assumption that of all the words of a language, you can make an ordered list of complexity. At its beginning there are “simple words”, for example, those that children learn at the very beginning of life: “mom”, “dad”, “good”, “bad”, etc. At the end are “difficult” words - professional vocabulary, archaisms, local adverbs, etc. In the simplified case, it is assumed that if a person knows a word in this ordered list, then he knows all the previous words in this list; if a person does not know a word, then he does not know the following words either. Thus, in the ideal case, a person’s vocabulary needs to determine the position of his knowledge boundary: the number of the last word he knows.

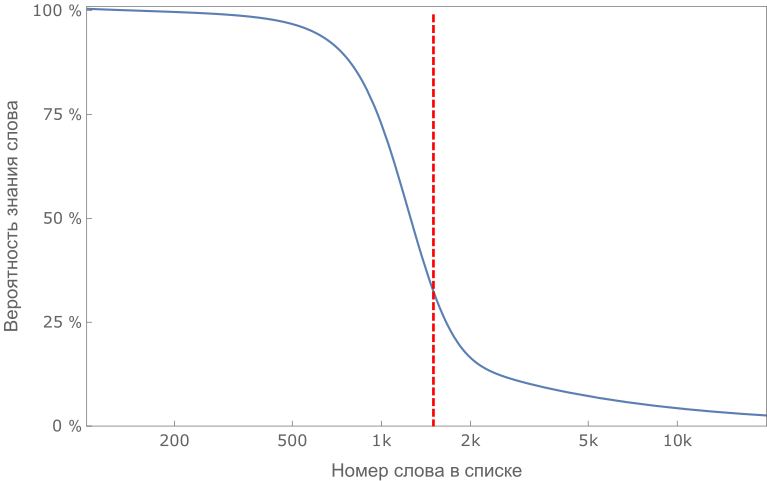

An approximate graph of knowledge of words in an ordered list in the ideal case. The border of "knowledge" accurately determines the size of the student's lexicon.

Such a perfect ordering of words, unfortunately, is impossible, because the real lexicon of different people is different (unless, of course, it is not zero). The study of words does not occur consistently according to the list approved by someone from above, it is influenced by the chosen program, teacher, personal and professional interests of the student. So, the mathematician and the doctor know the terminology of their fields, but they are not aware of terms not from their own field; they will perceive the complexity of the words "differential" and "carcinoma" in different ways.

Therefore, it makes sense to talk about the average word ordering. In this case, the concept of a clear boundary is missing: a student may know the word No. 1000, not know the word No. 1001, and again know the word No. 1002. To describe real situations it makes sense to consider the following approach.

We divide the words in our list, ranked by complexity, into intervals (for example, 100 words) and for each interval we determine the percentage of words from this interval that the student knows. The result is a relatively smooth curve; if we know the number of a word, then with the help of the graph we can see with what probability the student knows it. For this function, you can determine the median: such a number of words that the number of unknown words before it is equal to the number of known after. This median will play the role of an analogue of the boundary and characterize the student's vocabulary numerically.

It looks great if it were not for one problem: how, in fact, to prepare the list of words in order of complexity?

The characteristic dependence of the probability of knowledge of a word by a student on the number of a word. The red vertical line shows the median of the distribution.

Frequency Analysis for the British Corps

There is a theory that the average complexity of a word directly depends on its prevalence (frequency). Indeed, the more often we get a word in the learning process, the faster we will learn it. Thus, an ordered list of words can be constructed by analyzing the frequency of all words in the body of texts - a specially selected and processed set of various texts of the language.

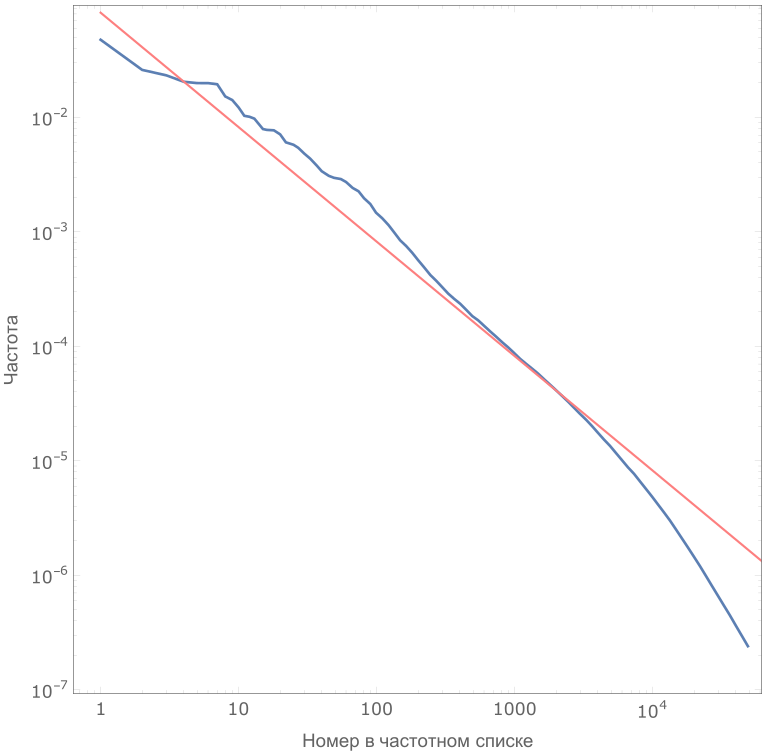

Therefore, we began by conducting a frequency analysis of the British National Corpus (British National Corpus). The corpus contains written texts (books, articles, documents), conversational (transcriptions of conversations, notes, films) and quotations from reports, addresses and speeches. These three subcorpuses differ in volume, but have the same importance for the analysis of a living language, so when calculating the frequency of their "weight" in the total result was equalized. Further, the frequencies were calculated and normalized by subcorpus (three results were averaged). Here is an excerpt from the resulting list and a plot of frequency versus word number:

| Word number | Word | Frequency (billion words) |

|---|---|---|

| one | the | 61 674 367 |

| 2 | be | 35,206,532 |

| 470 | leader | 2,420,806 |

| 5175 | millennium | 11,433 |

| 49818 | negligibly | 67 |

The dependence of the frequency of a word on its number in the list. It can be seen that the beginning of the list is well described by Zipf's law (red line).

The subjectivity of the concept of complexity

The statement about the good correspondence of the frequency of words in the corpus of texts and the relative orderliness of the lexicon of a group of people is true only if this group is an active reader and producer of these texts. In other words, the British corpus reflects the orderliness of the lexicon, above all, of the British, to a lesser extent of other English-speaking societies, and, last of all, of Russian-speaking learners of English.

As an important example of such a discrepancy, one can cite words of Greek, Latin, or other origin, which have a similar form in English and Russian. For example:

| English word | Russian word |

|---|---|

| analysis | analysis |

| moment | moment |

| information | information |

| philosophy | philosophy |

| bronchitis | bronchitis |

| doctor | doctor |

In total, we have allocated more than 5 thousand such words. What makes such a similarity of forms in two languages? If a student is more or less able to read English, it will be easy for him to guess the meaning of the word, although he never taught him (unless, of course, this is not a “false friend of a translator” like a magazine).

It should be noted that this effect has a positive effect on the size of the passive dictionary; however, it has practically nothing to do with the active one. On the one hand, the student is guaranteed not to know in advance whether the Russian word has a similar translation in English, and on the other hand, phonetics and spelling often differ significantly. Nevertheless, the study of these words cannot be put on a par with English-speaking English-language lemmas of Anglo-Saxon origin, for which the student has to memorize all lexical units (spelling, phonetics, translation) without any prompts from the native language.

Even an analysis of the frequency list of words of speakers of the English language shows its strong dependence on time and place. For example, a comparison of the famous Salisbury Word List, which shows the most frequent words of Australian schoolchildren in 1978–79, and Oxford Wordlist, vocabulary studies, again for Australian schoolchildren, but 30 years later, shows that in the vocabulary of modern children, words related to consumerism: bought, new, shop, want and technology, whereas before that most of the frequency words were devoted to the topic of family and leisure.

All this convinced us that the list, sorted only by frequency, was not good enough for our purposes - teaching English to Russian-speaking students - which led to the launch of the WordMash project.

Custom Wordmash project page, in which the user chooses two words that are simpler in his opinion.

Smart ranking

WordMash is an additional dictionary sorting tool based on the subjective perception of the complexity of individual lexical units by real people, our students. Of the two words proposed by the system, the user chooses the most, in his opinion, simple. At the same time, the Elo rating system is used to organize the list. This system, which originally appeared in chess, is now used in many games and sports, from Go to Magic the Gathering.

Its essence is that the amount by which the ratings of players change after each meeting (match) is not constant; it depends on the initial rating of each of the rivals (probability of victory). If the obviously stronger player (grandmaster) beats the obviously weaker (novice) player, the winner will receive, and the loser will lose the minimum number of rating points, which tends to zero in extreme cases. On the contrary, if the grandmaster loses in the same situation, he will lose a significant part of his rating. Thus, the higher the rating - the harder it is to raise and easier to lose, but a talented beginner can achieve an adequate assessment of his skill quickly enough.

At the beginning, the initial rating was calculated for all words as the logarithm of the frequency:

Then, if the i-th word was compared with the j-th, the number of points was written out, which scored the i-th word equal to 1 if the i-th word was simpler than the j-th (win), 0 - if the i-th word turned out to be more difficult (loss), and 0.5 - if the user found it difficult to answer (draw). The score remained:

. On the basis of current ratings, the expectation of the number of points scored by the i-th word was calculated:

Finally, a new word rating is calculated:

Thus, the most simple words rise in the ranking, and complex, on the contrary, fall.

Note that such a technique with a certain size of the user base is resistant to the noise of the results. In other words, the word rating obtained on the basis of the answers of one user cannot be considered reliable, however, as the number of participants in the program grows, its accuracy constantly increases.

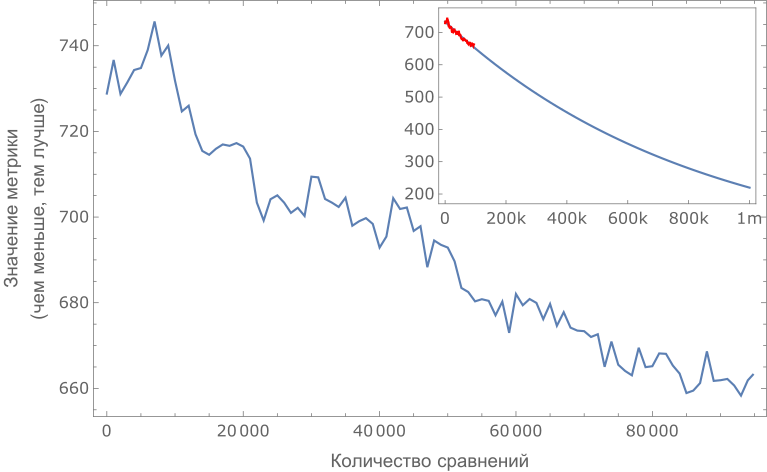

To test the validity of the method, we conducted an experiment with sixteen volunteers with different levels of language knowledge. They were given a list of the first 8 thousand words of the original frequency list, in which they noted the words they knew. For each word, the percentage of people familiar with it was calculated, and using the interval method described above, a cumulative distribution of the knowledge of the words “average person” was constructed. This distribution turned out to be non-monotonous: some of the words in the list below turned out to be simpler than the words in the list above. After 85 thousand comparisons, this curve turns out to be a little smoother.

A sorting quality metric was constructed: the number of permutations that must be made in the word list in order for the curve to become monotonous (the fewer the permutations, the better). The graph below shows how this metric depends on the number of comparisons made.

Improved word sorting (falling metrics) in the process of accumulating data on paired comparison of words by users. Improved sorting suggests that the WordMash method works and leads to the desired result.

Unfortunately, like many other methods, WordMash is most effective at initial sorting, but more and more comparisons are required to achieve more accurate results. We received an estimate of the required number of comparisons (of the order of a million) as a result of extrapolation.

We cannot do so many comparisons on our own, so we opened the tool for volunteers at http://tools.skyeng.ru/wordmash . To do this, we had to consider additional algorithms for screening out random results, which may arise as a result of self-indulgence, as well as the “favorite button effect” or simply the user's fatigue. Any number of such random results will still leak into the database, but at the scale of the research that we have conceived, they will be within the limits of statistical error.

Definition of student vocabulary

With the results of the WordMash tool in our hands, we will be able to accurately determine the volume of the student’s vocabulary, which will allow us to more accurately select training materials for him. The growth schedule of this volume, in turn, serves as a good motivating factor and an indicator of learning effectiveness. To define vocabulary, we use a tool similar to Test Your Vocabulary , but with a modified WordMash base of word complexity.

At the first iteration, asking a few words that logarithmically evenly cover the entire range of the ranked list, we find an approximate border by the median method. At the second iteration, we clarify this boundary by asking words in the neighborhood of an approximate boundary.

It should be noted that in the case of logarithmically distributed values, the median method of determining the boundary should be slightly modified (corrected for word density). If word numbers distributed logarithmically evenly:

where k = 1, 2, 3, etc. but

- constant, and we got student answers

which are equal to 1, if he knows the word and 0, if he does not, then the bound estimate will be:

Thanks to the word ranking and vocabulary definition tools for the student, we can increase learning efficiency by creating services that complement our ecosystem well — for example, “Heat Map of Text” (meaning the student knows how to know words in color) or WordSet Generator (word list creation tool for learning on based on specific texts and student level). Possessing a rather truthful, ordered by complexity list of words, we can finely tune the lessons to the needs of a particular student — so that they are interesting (contain new useful information) and not overly complex (when there are more than twenty unknown words in the text).

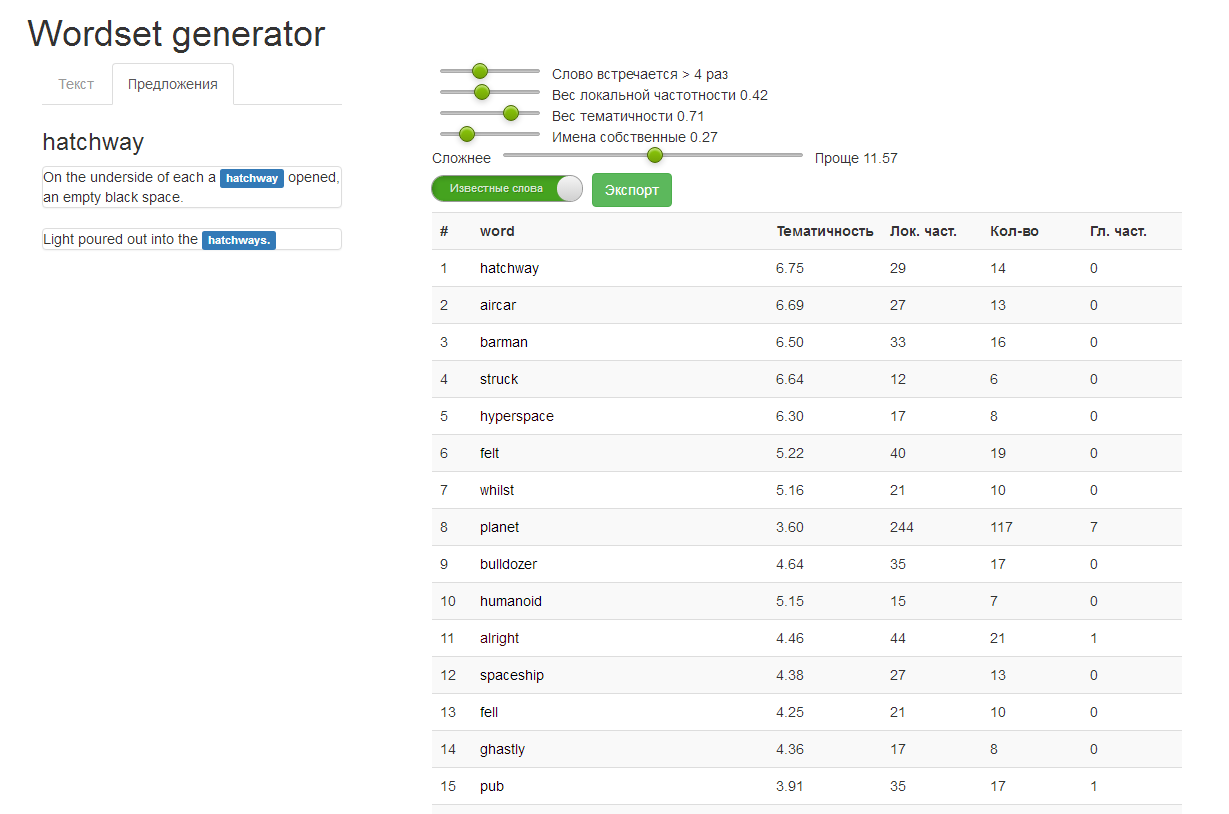

A prototype of the Wordset Generator tool with Douglas Adams' Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

Now the WordMash tool has been launched, we are recruiting the necessary base of a million comparisons and asking readers to take part in the experiment. If you have a free minute, please go to the site and rate a few pairs of words with the arrow keys. In total, you will be offered ten thousand pairs, but it is not necessary to go through all of them - we save the data after each comparison.

Having listened to the commentators here on “Habré”, we made WordMash open: in order to compare words, it is not necessary to register, the progress will be saved using cookies. However, if you are willing to spend a considerable amount of time on comparisons, we recommend registering so that, firstly, you can save individual statistics, and secondly, you know who to give a free lesson as a thank you. In addition, with the registration, we can guarantee that the history of your comparisons will not disappear anywhere. We store the results for future analyzes, identification of patterns and even more fine-tuning of individual training programs.

')

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/301214/

All Articles