Gothic Recognition: how we helped digitize the National Library of Latvia

Today we want to tell you how the publications of the National Library of Latvia were digitized. If you follow our blog, you probably read how our technologies help digitize the literary heritage of various libraries , as well as articles on individual projects - digitization in the Sakhalin Library , the Royal Botanical Garden of Edinburgh and the Hartley Library . Today is a story about how it was in Riga. So, the National Library of Latvia - the largest in the country, founded in 1919, has a 4.5 million collection of books and documents, including in the Latvian language in a unique Gothic writing.

Since the XVI century, the recording of all texts was conducted in Gothic type, confirmation of this is the oldest printing monuments in Latvian: the Catholic Catechism P. Canisia (Vilnius, 1585) and the Small Catechism by M. Luther (Koenigsberg, 1586). Gothic font was used to write the Latvian language until the twentieth century. The most interesting thing is that it differed from the many familiar (and already familiar to us) German languages in the Gothic version.

')

It was originally planned to process materials that are physically damaged or popular among readers, or are considered historically important. They had to be “saved”, at least in digital form. The approximate amount of work was 2.5 thousand pages of periodicals, which is equal to about 1000 of the publications themselves and 1.5 million pages of books - about 7,000 pieces.

Dating history

By the time of our acquaintance, the library had already collaborated with a digitization service provider company, which, in turn, used ABBYY OCR technologies. But it was impossible to recognize scans - the problem was that our technologies could not “see” Latvian Gothic correctly, since they were not trained in such symbols. Then the library turned to ABBYY.

Gothic Recognition

By that time, our ABBYY FineReader Engine had already supported the gothic font, but the Latvian gothic was different from the similar and known German one. To teach the product a new font, I had to add a lot of new characters.

A package of images came from the library. This is part of the first package.

We took a small part of the images from this package and divided it into two bases: a training one, according to which graphemes are taught, and a test one, with which we verify the correctness of recognition. Grapheme is a specific way to graphically represent a symbol. The relationship between symbols and graphemes is quite complicated - in European languages, a single grapheme can correspond to several symbols (a small "c" and a large "C" in Latin and Cyrillic are all one grapheme), and a single symbol can correspond to several graphemes (the letter "a" in different fonts may be indicated by different graphemes).

We add graphemes, and then for each grapheme with the help of classifiers (we have several, for example, omnifont, contour and raster - we wrote about the work of classifiers here in detail) feature vectors are selected so that many images of this grapheme are divided into groups (clusters) , inside each of which all the images are most similar to each other and at the same time the images from different groups were not as similar as possible. Thus, it is possible to calculate the basic confidence that a character encountered in text recognition is some kind of grapheme (it will belong to a certain cluster of this grapheme with some certainty).

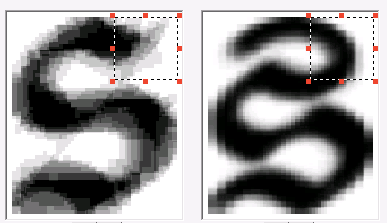

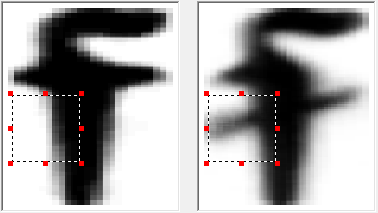

In case there were several possible options for recognition of the same image, differential pairs are compiled. These are pairs of different graphemes, which are similar to each other and, accordingly, can be confused. For such couples, different traits are distinguished by which they can be distinguished.

Some of them are shown below.

After all the signs are described and the program on the test package of images shows less than 5% of errors (95% accuracy is generally sufficient to assume that we support the language as a first approximation), the work on adding a font can be considered complete. In total, we added 39 characters. We made a version of the FineReader Engine with a new font and sent it to the library. A little later we were sent another batch of images - there were characters in it that were not in the first batch. And everything started all over again - of course, the new introductory ones turned out to be smaller in terms of volume, anyway, the technology had to be “retrained”.

Change is inevitable

Finally, the FineReader Engine with Gothic support in Latvian writing was ready. When we sent it to the client, it turned out that the library had ceased to cooperate with the former digitization service provider. For us, this meant that there was no one to embed our SDK into the final product, which was supposed to recognize the books. We had no choice but to convert the Engine into the final product - as a result, in one day we made an application that took all the images from one folder and put the recognition result in a given format into another folder - a very much simplified analogue of ABBYY Recognition Server . In the meantime, the library management was looking for a replacement for a company that provides digitization and maintenance services for library software. The choice fell on the German company CCS, which has already worked with our products and technologies. It was enough for them to simply embed a ready-made Engine with a gothic font in their system and start working.

And, as is customary in such stories, there are some statistics at the end. A little more than a year it took to process 4 million pages of ancient books and modern editions. During the peak periods of the project 60, scanning and verification operators had to work on three eight-hour shifts daily.

Digital versions of the books of the National Library of Latvia can be found at www.periodika.lv .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/300918/

All Articles