Sociology of Algorithms: How Financial Markets and High Frequency Trading are Connected (Part 2)

Earlier in our blog we published the first part of the study of the sociology of financial algorithms, performed by the professor of the Edinburgh School of Social Sciences Donald McKenzie. Today we bring to your attention the continuation of this interesting work - the second part deals with different types of HFT applications, dark pools and related ecologies of financial markets.

Reg NMS and ISO applications

The decision to create the Intermarket Trading System (ITS), made in the late 1970s, and the emergence of a “bundle” between HFT trading, trading platforms and government regulation still affect the trading of stocks in the United States. But the contradictions that have arisen during this time, in recent years, have become increasingly apparent. In 2005, after 30 years of controversy over how to organize trade in the US stock market, the SEC commission introduced several rules on the basis of which this trade is built today. All rules are fixed in the Regulations of the national market system [eng. Regulation National Market System]. Reg NMS, as they are called these regulations, emphasizes the importance of the processes, once launched in a "bundle". In accordance with the Regulations, the person making the order on the exchange could no longer “protect” it, since the algorithms could simply “circumvent” this application. "Secure" now were only applications that were almost instantly submitted or executed by algorithms. As a result, the SEC commission achieved its goal: according to estimates of Angel, Harris and Spatt (2013), in just four years the share of the NYSE in trading shares placed on this exchange fell from 80% to 20%.

')

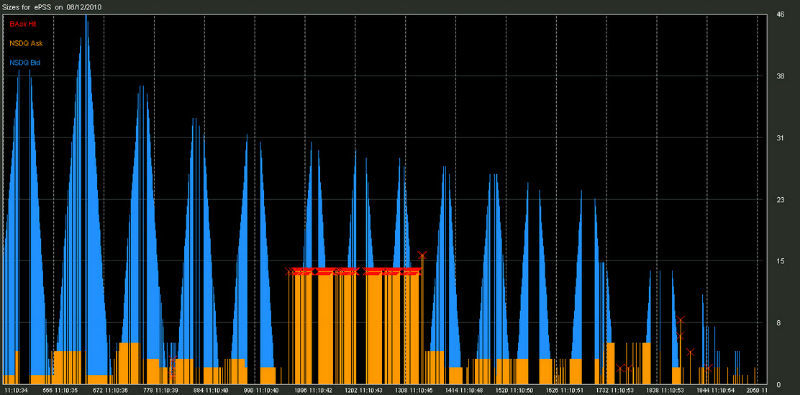

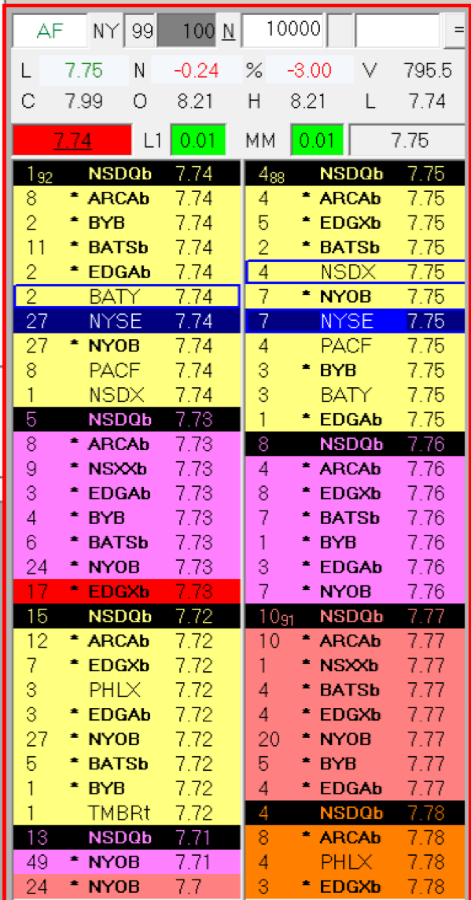

At the same time, Reg NMS resembles the ITS system in its structure and organization of economic interaction. The activities of each of the trading platforms, as in the ITS system, are subject to the rules on the "protection" of quotations and the prohibition of trading at less favorable prices. For example, consider the order books presented in Figure 1. Here, “the best national sale application” [eng. national best bid] Astoria Financial shares may be priced at $ 7.75. This means that all sales orders for this price are “protected”. Reg NMS prohibits selling Astroria shares at a price above $ 7.75: this violates the rule to ban trading at lower prices. Similarly, Reg NMS prohibits “blocking” [eng. lock] other sites. Suppose NASDAQ received a bid to purchase 1,000 shares of Astoria at $ 7.75. Out of 1000 shares, the stock exchange may acquire only 488, since it cannot bid for the remaining 512 shares at $ 7.75. The fact is that “protected” applications for the purchase of shares for $ 7.75 are available at other sites, so this bid should go to them. If the NASDAQ could put this bid, then all other sites would be "blocked."

Figure 1 - Applications for the purchase and sale of shares of Astoria Financial Corp. on the US marketplaces, noon October 21, 2011. Source: one of the interview participants

The above “rules for the protection of applications” Reg NMS - partially borrowed from the ITS system - force developers to write additional algorithms. These algorithms should monitor whether applications are being traded at lower prices and that “protected” applications are not “blocked”. To do this, they verify each application with the NBBO. National best bid and offer - the best national bid and offer], which are published in the exchange report. [21]

Such "testing" algorithms have a great influence on the interaction of HFT algorithms as a whole. First, the verification requires additional time, thereby reducing the rate of issuing and execution of the application. Secondly, the algorithm has to compare the already “outdated” data, since the exchange report is transmitted more slowly than the data from the engines for the information of buyers and sellers. Thus, the HFT algorithm can “see” that the “protected” orders from the exchange report are no longer relevant. Thirdly, the verification of compliance with the rules of Reg NMS imposes restrictions on “aggressive” HFT algorithms, which are often executed simultaneously for several applications with different prices. Execution of such orders will be postponed until all of them obey the rule prohibiting less profitable trading. Fourthly, Reg NMS also affects the operation of HFT algorithms that add liquidity: placing their bids will be postponed until they stop “blocking” other sites.

However, Reg NMS makes an exception for a special type of application, which the "reducing" engine can place and execute without unnecessary checks. This type of order is called intermarket sweep orders [Eng. intermarket sweep order, ISO], or ISO applications. [22] Each ISO application is marked with a special flag that is recognized by algorithms. The presence of a flag indicates that, together with an ISO order, the company submitted bids that help remove “protected” quotes from other trading platforms. Otherwise, the ISO application would be executed at a less favorable price or “blocked” other sites (that is, would violate the rules of Reg NMS).

It is through the use of ISO orders that the contradiction between the processes generated by the “bundle” and the consequences of the introduction of the ITS system is resolved. HFT firms with high-speed access to market data using ISO applications can bypass Reg NMS, thereby gaining a significant speed advantage. However, not everyone can use the ISO-flags in their applications. They can be used only by registered broker-dealers who need to submit their orders before the others.

At the same time, the use of ISO applications indicates a contradiction between the “bundle” and the changes made in the field of state regulation. Most companies aiming to add liquidity try to circumvent Reg NMS in different ways and gain speed advantage. In 2012, a lot of controversy arose after Heim Bodek, the founder of Trading Machines, which deals in options trading, was interviewed by the SEC and the Wall Street Journal. He said that trading platforms are developing special types of orders that help liquidity-adding companies get around Reg NMS. [23] The response of HFT trading experts to Bodek’s interview was mixed. Some argue that the description of the principles of these applications has long been in the public domain. Others believe that such applications have always been used, and journalists have only recently found out about them.

Dark pools and alignment using algorithms

Such "technical" solutions, such as ISO orders and special types of applications, only partially resolve the described contradictions. Another way to eliminate them is to build boundaries. HFT companies that specialize in adding liquidity describe their algorithms as “more correct” compared to those that take liquidity. They require that they be considered "electronic market makers", therefore, taking on the role of this role, HFT firms often try to "delineate certain boundaries." This process is discussed in detail in the work of Viviana Zelizer (Viviana A. Zelizer, 2012).

As has been said, some HFT companies point out the difference between their actions and the actions of the "opportunistic" algorithms of other companies. The problem is that the border between them is rather blurred, since the market maker algorithms often also have to take liquidity to reduce risks. None of the HFT companies I know can fully protect their algorithms from liquidity absorption.

Another type of algorithmic activity that can be considered “unfair” is called “algorithmic sniffing” [Algo-sniffing]. Its essence lies in the fact that the HFT algorithm monitors the actions of the execution algorithms in order to “cash in” on them. HFT companies, as a rule, deny the use of algorithmic sniffing. However, interview participants who are experts in this field said that some firms use machine learning methods in their algorithms, on the basis of which the algorithm itself reveals general patterns and allows making fairly accurate predictions.

The question remains whether the electronic market-making should be “fenced off” from “aggressive” HFT trading and algorithmic sniffing. For example, a BI respondent notes that liquidity absorption does not contradict the activities of market makers. He calls this kind of activity “non-forgetting liquidity.” The interview participants recognized the “legitimacy” of algorithmic sniffing and even spoofing. According to one broker, players who use "execution algorithms to hide the real balance of supply and demand in the market are no better than those who carry out algorithmic sniffing."

Despite the difficulties encountered in building the boundaries between market-making and other types of HFT-trading, the owners of trading platforms are trying to draw a similar distinction. To this end, in 2011, Credit Suisse launched a new “light” platform, Light Pool. All the players could see the order book on this trading platform. However, from the point of view of building the boundaries of particular interest are dark pools [eng. dark pools] - trading floors where players do not see what is happening in the order book. The most well-known dark pools are Crossfinder (owned by Credit Suisse), Sigma X (owned by Goldman Sachs), LX (formerly owned by Lehman Brothers, now Barclays platform) and ATS (owned by UBS).

The goal of almost all dark pools is to organize trade between "natural" players, and in such a way that the requests of these players cannot be seen by HFT traders. (“Natural” players are called large investors who really want to buy or sell a large package of financial instruments). However, there may be “unnatural” players on the market who are not going to sell or buy anything. Therefore, in order for the dark pools to remain liquid, professional traders should take part in trading on them. According to the 2013 data given in the article by Angel, Harris and Spatt (2013), about 15% of trading in the US stock market is conducted in dark pools, and the volume of transactions was far from as large as before. As Massoudi and Mackenzie (2013) write, after the arrival of HFT traders, the average transaction size in most dark pools — about 200 stocks — no longer exceeded the size of transactions in the “light” markets.

The main feature of the dark pools - the presence of an invisible book of applications - does not allow HFT-algorithms to make predictions based on the "dynamics of the book of applications". However, other forecasting methods allow electronic market-making, which is necessary to increase the liquidity of the dark pools. At the same time, the existing contradictions are aggravated by the fact that HFT traders are suspected of leaking information from dark pools. So the AE respondent calls pools “harmful” [eng. toxic]. Many fear that if HFT algorithms can detect large applications in dark pools - for example, using “pinging” [Eng. pinging] the book of applications (by continuously sending out small applications to check if someone else is executing them) - then they will be able to make a profit from trading in "bright" markets.

Large investors are unlikely to want to trade in “bad” pools, so the owners of these sites need to convince investors that pools control the actions of all algorithms. The owners of the dark pools, whose technical solutions create obstacles for HFT trading, said they are able to track all the actions of algorithms and other players in their market. The majority of respondents, one way or another connected with dark-pools, are sure that the measures taken on their trading floors do not allow "opportunistic" HFT-algorithms to take liquidity from dark-pools.

To determine whether the algorithm is "opportunistic", it is necessary to analyze a large amount of data. Therefore, the alignment of borders for the most part carried out with the help of algorithms. One of these methods is to assess the company's short-term profitability. To do this, it is enough to track how much the prices of the shares traded by this company have increased a second after the transaction. Too much profit is considered an indicator of opportunism. It is also possible to take the volume of absorbed liquidity as a variable: if the indicator is too high, then, most likely, trade is conducted using the “opportunistic” algorithm. Interestingly, only two out of seven respondents considered such an activity “legitimate”. The rest said that "this is just a business."

As mentioned earlier, a similar boundary is drawn between the HFT companies themselves. Moreover, the fact of tracking the actions of other players, as one respondent put it, automatically classifies the company as “good guys.” Some HFT companies fundamentally refused to trade on sites where the actions of their algorithms could be tracked. Others were not against it and were even going to set up their algorithms so that they could make money from it.

“Additional verification” and related ecologies of the foreign exchange market

Another place where the actions of HFT-algorithms are limited and monitored by the owners of trading platforms is the foreign exchange market (FX). And here these measures are even more serious than in dark pools. Initially, currency trading was carried out not on exchanges, but directly between players (the so-called “over-the-counter trading”). [24] Prior to the introduction of ECN systems, the FX market on the NASDAQ was and for the most part remains “dealer”. Most of the market players - small banks, hedge funds and large investment companies - did not trade and now practically do not trade among themselves: they conclude all transactions with dealers, agreeing to the prices offered by them (in the foreign exchange market the main dealers are large banks). Dealers, in turn, traded and continue to trade through inter-dealer brokers, messaging systems, or one of two inter-dealer trading platforms - Reuters or EBS. [25]

In the late 1990s - early 2000s, just as the NASDAQ and the NYSE entered into the fight against ECN systems, dealer trading, which was conducted in the foreign exchange market, met with resistance from new electronic platforms created on the basis of the same ECN -systems These new trading platforms were similar to the so-called "avatars" described by Abbott: they were the "embodiment" of institutions from one area (stock trading) to another - in the FX market. However, as Abbott (2005) writes, “competition within the avatar ecology may lead to unintended consequences for it”. Initially, as one of the respondents stated, “everyone believed that the introduction of ECN systems in the foreign exchange market would force banks to adopt a new paradigm” - this happened in the case of equity trading. But banks, playing the role of dealers, "could refuse to participate" in the development of trading platforms that threatened their interests. And without the support of banks and the large volumes of liquidity that they could provide, the new trading floors in the foreign exchange market had little chance of success.

Thus, the interaction of new electronic sites with banks should have led to their cooperation. Automation observed in the FX market, often carried out taking into account the interests and preferences of the largest banks. For example, systems like the ultra-fast ITCH news feed and the OUCH protocol introduced on the Island trading platform were not common on the foreign exchange market. Instead, they began to use a much slower FIX protocol, since it was widely used among banks.

The main ecologies in stock trading were HFT trading, trading platforms and government regulation. As HFT trading emerged, on the currency market — of which players were often trading in stocks or futures — another set of related ecologies began to take shape. The ecology of the trading floors resembled a similar ecology on the stock market: two large trading currency exchanges (EBS and Reuters), several new sites like ECN systems and other sites controlled by banks. But, unlike the stock market, the ecology of trading floors in the foreign exchange market was closely connected not with regulatory authorities, but with large banks playing the role of dealers. If, when trading in shares, HFT companies acted more or less independently, then on the foreign exchange market, the HFT company needed a bank, which facilitated the trading process. [26]

In the foreign exchange market - however, as in all other markets - banks relate in two ways to HFT trading: on the one hand, they receive income (for example, payment for primary brokerage [eng. Prime brokerage] services) from proprietary trading companies, on the other hand, HFT companies are considered to be their competitors. In addition, it is not entirely clear how the organizational structures of banks can contribute to the development of simplified, high-speed technical systems. In HFT companies, trading activities and the development of technological systems are closely intertwined: there is often no distinction between a trader and a developer in the organizational structure of companies. In banks, developers are part of IT departments, each of which, as a rule, has its own methods of work.

Given the dependence of trading floors in the FX market on banks, as well as the twofold attitude of the latter to HFT trading, it can be concluded that the measures to curb HFT trading in the foreign exchange market were more stringent and more widespread than in the stock market. One of the currency traders said that if the HFT-firm "is trading too successfully on the banking site and the bank finds out about it, then on the same day the company is excluded from the site." [27] As the AU respondent notes, the bank may simply say: “I don’t want to trade with them because they are too good. Let's get them off the ground. ”

The FX market also creates various “technical” obstacles for HFT traders. Platforms for trading stocks like Light Pool, dark pools, and IEX, described in the Lewis book (2014), are niche markets rather than mass ones. In the foreign exchange market, in turn, the larger players are trying in every way to prevent HFT-traders. Both EBS and Reuters set the minimum waiting time for the application. In particular, an EBS application must remain in the book for about a quarter of a second before it can be canceled. In 2012, EBS increased the size of one item five times and changed its algorithm to bring buyers and sellers to a slower one. This algorithm collects incoming applications in a heap and then processes them in a random order.

Speed is one of the main differences between trading floors in the stock market and the foreign exchange market. A distinctive feature of algorithmic trading in the foreign exchange market is the presence of the so-called "additional verification", which arose as a result of the main contradiction in the HFT industry. Before you make a deal, the “reducing” engine sends a message to the other player about this deal, giving it time (from 5-10 to several hundred milliseconds, and sometimes up to several seconds) to cancel it. In this situation, electronic platforms are directly dependent on banks, which are a kind of liquidity providers. A bank can dictate its terms to ECN systems and, for example, say: “If we do not carry out additional checks, we will not provide liquidity for your customers.”

Dealer banks believe that “additional verification” is necessary for organizing market activity in the foreign exchange market. Engines for the attention of buyers and sellers, banking systems and the FIX protocol in the FX market are slower than similar systems in the stock market. Thus, market activity in the foreign exchange market is quite slow. The dealer bank faces the risk that its applications will drastically change in price, and it will lose money even before it can cancel these applications. Therefore, an “additional check” allows him to ascertain whether it is necessary to conclude this transaction at all.

The ratio of HFT traders to “additional verification” is ambiguous. Speaking about trading in the foreign exchange market, respondent AK states that “if you are not a bank, then you will be considered a jerk.” His company managed to achieve small success in HFT-trading, after which one of its major transactions was canceled during the "additional check". “When we filed a complaint with the management of the trading platform,” says respondent AK, “we were told that, in accordance with their structure, some players check every incoming bid.”

Other HFT traders were not so strict with the “extra test”. BC respondent said that to succeed in HFT trading on the FX market, it is necessary to “build relationships” with banks. It is better to get a small but regular income than trying to extract the maximum profit at a time. The AU respondent notes that "the essence of trading in the foreign exchange market is that it is over-the-counter, algorithmic, and depends on the ability to build relationships." And often some players of electronic platforms pay too much attention to the first two components, forgetting about the latter.

Conclusion

With the growing share of algorithms trading in the market, there is a need to describe their interaction. In the framework of this article, the historical, environmental and “zelitser” aspects of the sociology of algorithmic trading were considered. Special attention was paid to HFT algorithms: their forecasting methods, interaction with the information engines and execution algorithms, as well as the processes of adding and absorbing liquidity. The article showed how the border is drawn between the “legitimate” and less or not at all acceptable actions of the algorithms, as well as how blurred this border is. In addition, the historical aspect of the sociology of HFT trading was considered and the sociotechnical version of the Andrew Abbott (2005) model of associated ecologies was used. The article explains how dependence on past events (in particular, making decisions about organizing economic activity in the late 1970s) and various connections between ecologies (with state regulation in the stock market and with major banks-dealers in the foreign exchange market) form algorithmic trading in the stock market and foreign exchange market. Significant differences between these markets give rise to contradictions, which, in turn, lead to various consequences - the emergence of intermarket sweep orders on the stock market and the introduction of an “additional check” on the foreign exchange market.

I have an assumption that all these processes (dependence on past events, various patterns within related ecologies, building boundaries) can be found not only in financial markets, but also in other areas where algorithms are the main actors. For example, from this point of view, one can consider an assessment of the borrower's solvency, described in detail by Martha Poon (2007, 2009). In addition, the article considers only one of the possible forms of interaction of algorithms. For example, we can consider the cultural sociology of algorithms on the example of the Island trading platform, which is not so much an economic as a cultural project. Concerns about the activities of HFT traders — the uncontrolled development of technology (examined in detail by Langdon Winner (Winner, 1977)) and finance (relevant in connection with the onset of the financial crisis) —can also be viewed from a cultural point of view.

The interview participants also talked about the need to improve the “relationship” in trading on the foreign exchange market, as well as how the change of personnel affects the variety of methods of HFT trading. These processes, in particular, can lead to the development of network sociology. «» , , , . [28] , , HFT- . , HFT- . , HFT-. « » , , .

, . , – .

, : , , «» , . , HFT- , 1970- . , FX «», HFT-, . «», SEC , .

, , «» «» , «» . , BH, «» «» . [29]

. , . , .

Notes:

21. NBBO [. Securities Information Processor, SIP] ( . , -, – . , -). SIP , NBBO. , , , .

22. ISO- Reg NMS 242.600(b)(30) SEC (2005).

23. Hide Not Slide, Direct Edge. , , Reg NMS.

24. , CME.

25. (Bruegger, 2002). (2007) EBS.

26. HFT- CLS. , .

27. HFT- , . .

28. HFT- : , - , HFT-, HFT-, , . , HFT- , , , , . . HFT- . HFT- . , BATS 2005 HFT- Tradebot -. 2014 Direct Edge – BATS Global Markets. NYSE, InterContinental Exchange.

29. , -, «» . , , , , , . , HFT-, «» , . « » [. adverse selection] : 0,1 HFT-, ( 0,3 ), , .

22. ISO- Reg NMS 242.600(b)(30) SEC (2005).

23. Hide Not Slide, Direct Edge. , , Reg NMS.

24. , CME.

25. (Bruegger, 2002). (2007) EBS.

26. HFT- CLS. , .

27. HFT- , . .

28. HFT- : , - , HFT-, HFT-, , . , HFT- , , , , . . HFT- . HFT- . , BATS 2005 HFT- Tradebot -. 2014 Direct Edge – BATS Global Markets. NYSE, InterContinental Exchange.

29. , -, «» . , , , , , . , HFT-, «» , . « » [. adverse selection] : 0,1 HFT-, ( 0,3 ), , .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/274671/

All Articles