John Horton Conway: Life is like a game - ending

First part

Arriving home, Gardner immediately showed Conway more than 20 articles devoted to calculating the day of the week for any date. Lewis Carroll's rule looked better than the rest. Gardner turned to Conway and said, "John, you need to develop a simpler rule that I can share with readers." And, as Conway says, on the long winter nights, when Mr. and Mrs. Gardner went to bed at home (although he came to visit them only in the summer), Conway thought about how to make this calculation simple enough so that it could be explained to the average man from the street.

He thought about it all the way home, and in the common room of the university, and finally thought of the “Doomsday rule”. The algorithm required only addition, subtraction and memorization. Conway also came up with a mnemonic rule that helped store intermediate calculations on the fingers. And for the best memorization of date information, Conway bites his thumb.

')

Over the years, Conway taught this algorithm to thousands of people. Sometimes in a conference room, a person of 600 is recruited, calculating each other's birthdays and biting their thumbs. And Conway, as always, tries to be unreasonable - he is already dissatisfied with his simple algorithm. From the very moment of development, he has been trying to improve it.

In addition to his periodic trips to Gardner, Conway wrote long letters to him in which he summarized his research. He used to insert a roll of paper (similar to the one into which the meat was wrapped) into a typewriter and printed letters, measuring them in length. Usually enough letters a little more than a meter long, although the record, according to Gardner's calculations, was equivalent to 11 regular pages.

He usually began letters with a preamble:

He then delved into the news of his research, starting, say, with his decision on the separation of the pie, moving to a new riddle with wire and thread, and then devoting most of the letter:

The Shoots were invented together with student Mike Paterson and were highlighted in the Scientific American column in July 1967. In response to a letter, Gardner sent a list of questions, starting with the question “What does H mean in the name of John H. Conway?”. After each question, Gardner left a lot of space on the sheet to enter the answer.

Conway's answer:

Gardner was also interested in the details of the origin of the game. “I predict that this game will become so generally accepted and well-known that the details of its creation will be interesting for the story,” Gardner wrote. - Could you tell us more about them? Did you draw scribbles at a lecture (if so, which one?) Or over a beer? ”

And Conway did not stop. The following letter was entitled:

IMPORTANT! BREAKTHROUGH IN EARTHLANDS!

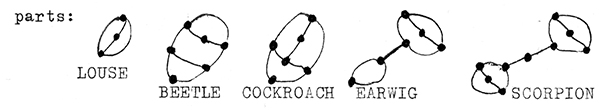

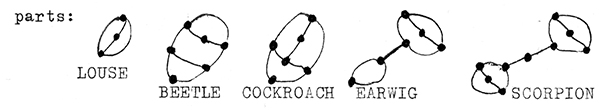

Named Positions: Woodlouse, Bug, Cockroach, Earring, Scorpion

Today, the “The World Game of Sprouts Association” exists, which is “devoted to the study of the reality of shoots” and “serious research of the game”. She holds annual online championships. Only people can participate in them, because computer analysis of the game over the years has inspired some to write bots for the game. Conway recently learned about this association, but he had long been aware of the existence of computer programs playing the game.

In the early 90s, three scientists from Bell Lab and Carnegie Mellon University wrote a paper, Computer Analysis of the Shoot Game, which analyzed winning strategies up to n = 11. “After 11 points, their program could not cope with the complexity of the game,” Gardner wrote for his readers. After a couple of decades, two French students who decided to break the record wrote the GLOP program (in honor of the French comic character Pif le chien, who spoke glop whenever he was satisfied). They defended a doctoral thesis on this topic, and claim that they found winning strategies up to n = 44. Conway was very interested and surprised by this:

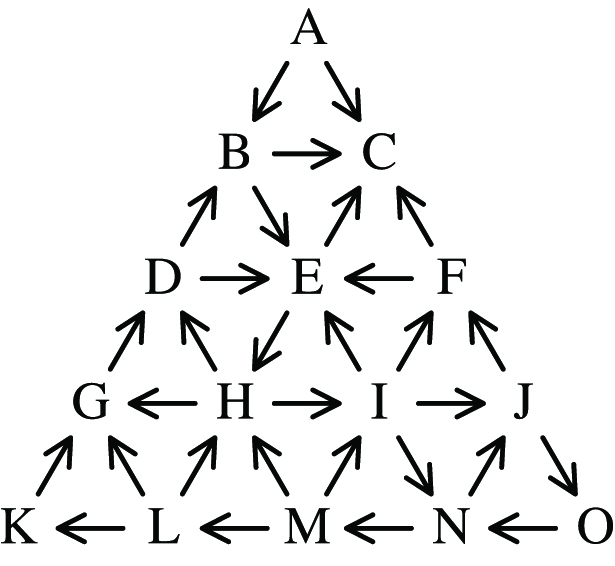

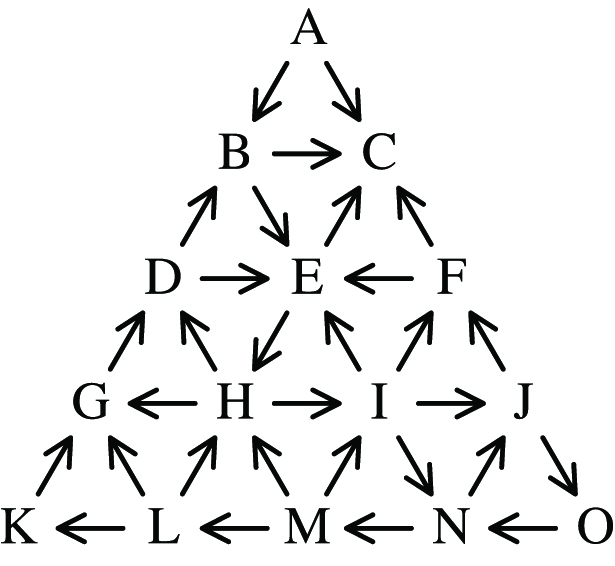

Another example of Conway’s genius is the “Traffic Jams” game, in which an imaginary country has a triangular map and cities are represented by letters. All letters are the first letters of the names of real cities - Aberystwyth, Oswestry and Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantantyiliogogogoch .

I suspect that Conway invented the game just to once again be able to pronounce the name of the city Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch. He saw him on a sign on the railway station and on the town square. Interestingly, these signs differed by one letter. As for the game, her question was - what is the first step the player should take?

In Cork, four players start with Aberystwyth (A), Dolgellau (D), Ffestiniog (F) and Merioneth (M). They take turns moving along one-way streets between cities. The game ends when all players get stuck in Conwy, from which there is no way out. Loses one whose turn was to be next.

All these games supplied data for Conway's theory of surreal numbers. The best experimental players were his own daughters, Susie and Rosie, 7 and 8 years old.

By happy coincidence, during this period (about 1970), the British champion of Guo, John Diamond, studied at Cambridge. He founded the Go Society and constantly played the game in the common room. Diamond, now the president of the British Go Association, does not remember having played with Conway at least once. Conway usually stood nearby, looked at the board and pondered over the moves of the players.

Conway recalls:

And this, in turn, prompted him to an even greater predilection for games. He always had all the necessary accessories with him so that he could suddenly fall on his opponent. In his leather case there were always cubes, drafts, a board, paper, pencils, a rope, and several packs of cards. Card games and tricks he succeeded. His analysis of games evolved from simple games to compound games, to cases where a player simultaneously played several games at once (sometimes, for example, chess, go and Domineering), and the player chose which game to go to. And he filled the paper rolls with the analysis of these games. As he told the reporter for Discover magazine:

And all this has evolved in order to become surreal numbers as the result - the largest expansion of the set of real numbers. The name they gave the computer specialist from Stanford Donald Knut. And since then, Conway has not worried about the workaholic Professor Frank Adams and about pleasing him and his colleagues. He realized that this discovery, which came from "stupid games", was already related to serious mathematics. After a period of 12 months, he came up with surreal numbers, invented the game “Life” and discovered Conway’s groups, he took an “oath”: “And you will end up worrying and feeling guilty, and you will do what you want ". He surrendered to his natural curiosity, went where it led him - at least to entertainment, at least to research, at least to some non-mathematical place.

Gardner summarized the theory of surreal numbers as “Vintage Conway: deep, innovative, exciting, original, brilliant, witty, and different Carroll puns. And on a trivial foundation, Conway builds a huge and fantastic building. But what is it dedicated to?

Conway in his work entitled “All numbers, big and small,” puts the question easier: does this structure have any benefits?

"It’s on the edge of entertainment and serious math," says Paul Halmos, an American mathematician of Hungarian descent. “Conway understands that she will not be called great, but she can try to convince you that she’s just like that.” On the contrary, Conway believes that surreal numbers are a great thing, without any “can.” He’s just disappointed that they haven’t yet led to even greater things.

And where do they put him on the path of the ancient intellectual journey to beauty and truth? Conway sees himself as a member of an orchestra parade marching through the streets of time. In the top 10 of the Observer newspaper, Conway is mentioned among mathematicians whose discoveries have changed the world. But try discussing this list with him, or another list in which he recently found himself - in the book “The Miracles of Numbers” by Clifford Pikovera, entitled “The Ten Most Influential Mathematicians of Our Time” ... He will immediately object:

Conway considers Archimedes the father of mathematics. It was he who understood the real numbers, and was the first who calculated the number π and limited it to the top 3 1 ⁄ 7, and from the bottom - 3 10 ⁄71. But in the Observer ranking, Pythagoras comes first. If he is not the best, he is known more than others, mainly due to the theorem of his name. And usually in these lists are Euler, Gauss, Cantor, Erds. Conway goes at the end, followed by Perelman and Tao.

Convey's youthful age came in the 70s and unlimited 80s. In the 80s, he divorced his first wife and married a math Larisa Queen, starting a new family. He became a member of the Royal Society and Professor of Cambridge. And then transferred to Princeton in 1987. We are still too close to Perelman, Tao and Conway to properly evaluate their contribution to science - especially how their abstract theories can be useful in practice. This analysis will take a long time.

An interesting exception was John Nash, Conway’s colleague in Princeton, about whom the book was written and the film “Mind Games” was shot. Nash made a contribution to game theory, which was immediately useful in evolutionary biology, accounting, politics, military theory, and a market economy, which led to his receiving the Nobel Prize in economics. From Conway’s point of view, the work that earned Nash Nobel Prize was less interesting than the Nash theorem on regular embeddings (any Riemannian manifold can be isometrically included in Euclidean space). Conway aimed at receiving the Abel Prize ("Nobel for Mathematicians"). He won a bunch of other prizes, but with the Abel Prize, nothing comes out yet.

And the practical application of his work has yet to be opened. Few doubt that at least one of his creations can be used. For example, surreal numbers. “Surreal numbers will be used,” said his colleague, Peter Sarnak. “The only question is what and when.” Sarnak praises Conway at all. “Conway is a seducer,” says Sarnak, referring to Conway’s talent as a teacher and interpreter, whether it's classes with students, a math camp, a lecture at a private party, or his alcove in the Princeton common room.

He can always be found in this alcove, where he is not busy working. And although he hopes to stumble upon other “hot” topics like surreal numbers, more often he plays with his favorite trivialities. He is never shy about catching a stranger and starting to overwhelm him with his own interests. One of the most recent is the " free will theorem " in which, in his opinion, every person is interested. It was developed over ten years in collaboration with a colleague Simon Kochen, and is formulated through geometry, quantum mechanics and philosophy. A simple formulation is: if physicists have free will when conducting experiments, then particles also have it. And this, in their opinion, explains why people generally have free will. This is not a vicious circle, but a more closed spiral that supports itself, but spins up and becomes more and more.

But usually he is most fascinated by numbers. He turns them, turns them over, turns them over and looks at how they behave. And most of all he appreciates knowledge and wants to know everything about the Universe. Conway's charm comes from his desire to share his knowledge of knowledge, to spread this passion and the romance associated with it. He stubbornly, stubbornly seeks to explain the inexplicable, and even when it remains unexplained, he manages to inspire an audience held together by a failed attempt, feeling part of one team, satisfied that they could flirt with a glimpse of insight.

Arriving home, Gardner immediately showed Conway more than 20 articles devoted to calculating the day of the week for any date. Lewis Carroll's rule looked better than the rest. Gardner turned to Conway and said, "John, you need to develop a simpler rule that I can share with readers." And, as Conway says, on the long winter nights, when Mr. and Mrs. Gardner went to bed at home (although he came to visit them only in the summer), Conway thought about how to make this calculation simple enough so that it could be explained to the average man from the street.

He thought about it all the way home, and in the common room of the university, and finally thought of the “Doomsday rule”. The algorithm required only addition, subtraction and memorization. Conway also came up with a mnemonic rule that helped store intermediate calculations on the fingers. And for the best memorization of date information, Conway bites his thumb.

')

Teeth marks must be visible! The only way to remember this. When I tell students about this method, I always ask someone from the first row to confirm the presence of marks from the teeth on the finger. You can’t force serious people to do this - they will decide that this is a kindergarten. But the point is that the whole thing usually does not linger in your brain, and you forget the date of birth, called you a person. But the thumb is able to remember for you how far this date is from the nearest “Doomsday”.

Over the years, Conway taught this algorithm to thousands of people. Sometimes in a conference room, a person of 600 is recruited, calculating each other's birthdays and biting their thumbs. And Conway, as always, tries to be unreasonable - he is already dissatisfied with his simple algorithm. From the very moment of development, he has been trying to improve it.

In addition to his periodic trips to Gardner, Conway wrote long letters to him in which he summarized his research. He used to insert a roll of paper (similar to the one into which the meat was wrapped) into a typewriter and printed letters, measuring them in length. Usually enough letters a little more than a meter long, although the record, according to Gardner's calculations, was equivalent to 11 regular pages.

He usually began letters with a preamble:

I received the first package with books right before Christmas, and I was so happy that I read them and re-read them for several days, especially “Alice” with comments (my wife is not happy with you!).

He then delved into the news of his research, starting, say, with his decision on the separation of the pie, moving to a new riddle with wire and thread, and then devoting most of the letter:

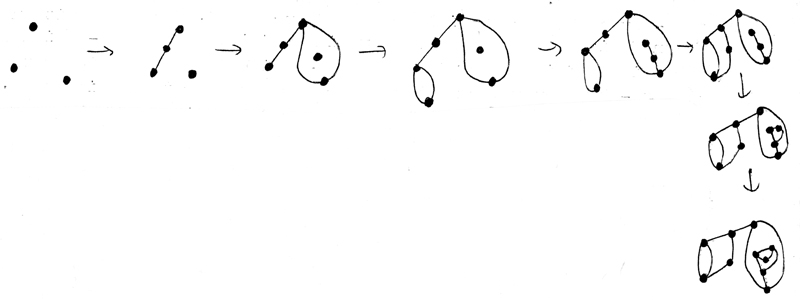

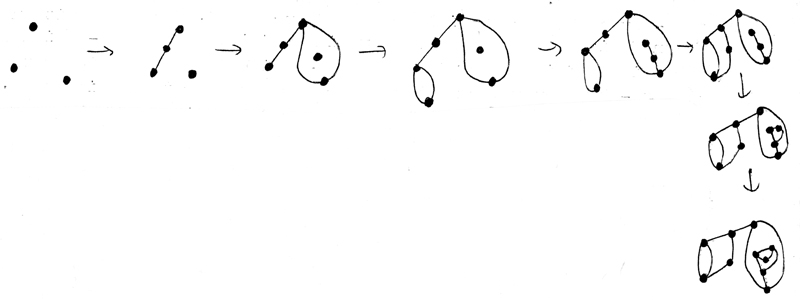

Shoots. We invented this game two weeks ago, during the day on Tuesday. By Wednesday, the entire mathematical department was infected with it, even the secretaries succumbed. We start with n points on a sheet of paper. A move consists in combining two points (you can combine a point with yourself) with a curve, and then in designating a new point on this curve. The curve should not pass through the old points, should not cross the old curves, and no more than three curves should go out from one point. In ordinary shoots the one who cannot make a move loses. In Shoots, Mizer loses the last one to make a move.

The Shoots were invented together with student Mike Paterson and were highlighted in the Scientific American column in July 1967. In response to a letter, Gardner sent a list of questions, starting with the question “What does H mean in the name of John H. Conway?”. After each question, Gardner left a lot of space on the sheet to enter the answer.

Conway's answer:

Horton And why so much space left? Did you think it would be something like Hogginthebottomtofflinghame-Frobisher-Williamss-Jenkinson?

Gardner was also interested in the details of the origin of the game. “I predict that this game will become so generally accepted and well-known that the details of its creation will be interesting for the story,” Gardner wrote. - Could you tell us more about them? Did you draw scribbles at a lecture (if so, which one?) Or over a beer? ”

We drew doodles after tea drinking in the common room of the department, trying to invent a game for pencil and paper. It was already after I conducted a complete analysis of one old game, in which there were points, but there was no addition of new ones - so that it did not have any “shoots”. It originated from one rather complicated stacking game that Mike Paterson turned into a game for pencil and paper, and we tried to modify its rules. And Mike said - why not add a point in the middle? And immediately all the other rules were discarded, the initial position was simplified to n points (initially - 3), and the shoots began to grow ...

The next day everyone seemed to be playing it. For coffee or tea, groups of people painted stupid or very complex drawings of shoots. Some have already done this on Klein bottles, etc., and one mathematician reflected on a multidimensional version of the game. Leaflets with batches could be found in completely unexpected places.

As soon as I try to introduce someone to her, it turns out that he had already heard about her somewhere. Even my daughters of 3 and 4 years old play it - although I usually win them.

And Conway did not stop. The following letter was entitled:

IMPORTANT! BREAKTHROUGH IN EARTHLANDS!

Named Positions: Woodlouse, Bug, Cockroach, Earring, Scorpion

Today, the “The World Game of Sprouts Association” exists, which is “devoted to the study of the reality of shoots” and “serious research of the game”. She holds annual online championships. Only people can participate in them, because computer analysis of the game over the years has inspired some to write bots for the game. Conway recently learned about this association, but he had long been aware of the existence of computer programs playing the game.

It was sad news. Computers were used to solve a number of open problems. They could solve problems that existed for 100 years. We wanted to invent a game in which it would be difficult to play a computer.

In the early 90s, three scientists from Bell Lab and Carnegie Mellon University wrote a paper, Computer Analysis of the Shoot Game, which analyzed winning strategies up to n = 11. “After 11 points, their program could not cope with the complexity of the game,” Gardner wrote for his readers. After a couple of decades, two French students who decided to break the record wrote the GLOP program (in honor of the French comic character Pif le chien, who spoke glop whenever he was satisfied). They defended a doctoral thesis on this topic, and claim that they found winning strategies up to n = 44. Conway was very interested and surprised by this:

Strongly doubt. They claim to have done the impossible. If someone claimed that he had invented a machine that would produce plays no worse than Shakespeare, would you believe them? It is very difficult, and that's it. This is how to teach pigs to fly. But I would be interested to look at their work.

Another example of Conway’s genius is the “Traffic Jams” game, in which an imaginary country has a triangular map and cities are represented by letters. All letters are the first letters of the names of real cities - Aberystwyth, Oswestry and Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantantyiliogogogoch .

I suspect that Conway invented the game just to once again be able to pronounce the name of the city Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch. He saw him on a sign on the railway station and on the town square. Interestingly, these signs differed by one letter. As for the game, her question was - what is the first step the player should take?

In Cork, four players start with Aberystwyth (A), Dolgellau (D), Ffestiniog (F) and Merioneth (M). They take turns moving along one-way streets between cities. The game ends when all players get stuck in Conwy, from which there is no way out. Loses one whose turn was to be next.

All these games supplied data for Conway's theory of surreal numbers. The best experimental players were his own daughters, Susie and Rosie, 7 and 8 years old.

By happy coincidence, during this period (about 1970), the British champion of Guo, John Diamond, studied at Cambridge. He founded the Go Society and constantly played the game in the common room. Diamond, now the president of the British Go Association, does not remember having played with Conway at least once. Conway usually stood nearby, looked at the board and pondered over the moves of the players.

Conway recalls:

They discussed their moves for the game, and the uninvited advisers around gurgled: "Why did you go so stupid?". And these bad moves for me looked just like good ones. I never understood go. But I realized that by the end it was divided into several games - inside one big game there were small games in different parts of the board. And this prompted me to develop the theory of sums of partisan games.

And this, in turn, prompted him to an even greater predilection for games. He always had all the necessary accessories with him so that he could suddenly fall on his opponent. In his leather case there were always cubes, drafts, a board, paper, pencils, a rope, and several packs of cards. Card games and tricks he succeeded. His analysis of games evolved from simple games to compound games, to cases where a player simultaneously played several games at once (sometimes, for example, chess, go and Domineering), and the player chose which game to go to. And he filled the paper rolls with the analysis of these games. As he told the reporter for Discover magazine:

An amazing surprise awaited me - I realized that there is an analogy between my records and the theory of real numbers. And then I realized that this is not an analogy - these were really real numbers.

And all this has evolved in order to become surreal numbers as the result - the largest expansion of the set of real numbers. The name they gave the computer specialist from Stanford Donald Knut. And since then, Conway has not worried about the workaholic Professor Frank Adams and about pleasing him and his colleagues. He realized that this discovery, which came from "stupid games", was already related to serious mathematics. After a period of 12 months, he came up with surreal numbers, invented the game “Life” and discovered Conway’s groups, he took an “oath”: “And you will end up worrying and feeling guilty, and you will do what you want ". He surrendered to his natural curiosity, went where it led him - at least to entertainment, at least to research, at least to some non-mathematical place.

Gardner summarized the theory of surreal numbers as “Vintage Conway: deep, innovative, exciting, original, brilliant, witty, and different Carroll puns. And on a trivial foundation, Conway builds a huge and fantastic building. But what is it dedicated to?

Conway in his work entitled “All numbers, big and small,” puts the question easier: does this structure have any benefits?

"It’s on the edge of entertainment and serious math," says Paul Halmos, an American mathematician of Hungarian descent. “Conway understands that she will not be called great, but she can try to convince you that she’s just like that.” On the contrary, Conway believes that surreal numbers are a great thing, without any “can.” He’s just disappointed that they haven’t yet led to even greater things.

And where do they put him on the path of the ancient intellectual journey to beauty and truth? Conway sees himself as a member of an orchestra parade marching through the streets of time. In the top 10 of the Observer newspaper, Conway is mentioned among mathematicians whose discoveries have changed the world. But try discussing this list with him, or another list in which he recently found himself - in the book “The Miracles of Numbers” by Clifford Pikovera, entitled “The Ten Most Influential Mathematicians of Our Time” ... He will immediately object:

On the one hand, nice. I may be one of the most famous mathematicians of our time - but this is not the same as being the best. And this is most likely due to "Life." But it confuses me. People might think that I'm lagging behind the best. But it is not. And in general, what else confuses me is that there is no Archimedes or Newton on these lists.

Conway considers Archimedes the father of mathematics. It was he who understood the real numbers, and was the first who calculated the number π and limited it to the top 3 1 ⁄ 7, and from the bottom - 3 10 ⁄71. But in the Observer ranking, Pythagoras comes first. If he is not the best, he is known more than others, mainly due to the theorem of his name. And usually in these lists are Euler, Gauss, Cantor, Erds. Conway goes at the end, followed by Perelman and Tao.

Convey's youthful age came in the 70s and unlimited 80s. In the 80s, he divorced his first wife and married a math Larisa Queen, starting a new family. He became a member of the Royal Society and Professor of Cambridge. And then transferred to Princeton in 1987. We are still too close to Perelman, Tao and Conway to properly evaluate their contribution to science - especially how their abstract theories can be useful in practice. This analysis will take a long time.

An interesting exception was John Nash, Conway’s colleague in Princeton, about whom the book was written and the film “Mind Games” was shot. Nash made a contribution to game theory, which was immediately useful in evolutionary biology, accounting, politics, military theory, and a market economy, which led to his receiving the Nobel Prize in economics. From Conway’s point of view, the work that earned Nash Nobel Prize was less interesting than the Nash theorem on regular embeddings (any Riemannian manifold can be isometrically included in Euclidean space). Conway aimed at receiving the Abel Prize ("Nobel for Mathematicians"). He won a bunch of other prizes, but with the Abel Prize, nothing comes out yet.

And the practical application of his work has yet to be opened. Few doubt that at least one of his creations can be used. For example, surreal numbers. “Surreal numbers will be used,” said his colleague, Peter Sarnak. “The only question is what and when.” Sarnak praises Conway at all. “Conway is a seducer,” says Sarnak, referring to Conway’s talent as a teacher and interpreter, whether it's classes with students, a math camp, a lecture at a private party, or his alcove in the Princeton common room.

He can always be found in this alcove, where he is not busy working. And although he hopes to stumble upon other “hot” topics like surreal numbers, more often he plays with his favorite trivialities. He is never shy about catching a stranger and starting to overwhelm him with his own interests. One of the most recent is the " free will theorem " in which, in his opinion, every person is interested. It was developed over ten years in collaboration with a colleague Simon Kochen, and is formulated through geometry, quantum mechanics and philosophy. A simple formulation is: if physicists have free will when conducting experiments, then particles also have it. And this, in their opinion, explains why people generally have free will. This is not a vicious circle, but a more closed spiral that supports itself, but spins up and becomes more and more.

But usually he is most fascinated by numbers. He turns them, turns them over, turns them over and looks at how they behave. And most of all he appreciates knowledge and wants to know everything about the Universe. Conway's charm comes from his desire to share his knowledge of knowledge, to spread this passion and the romance associated with it. He stubbornly, stubbornly seeks to explain the inexplicable, and even when it remains unexplained, he manages to inspire an audience held together by a failed attempt, feeling part of one team, satisfied that they could flirt with a glimpse of insight.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/274151/

All Articles