John Horton Conway: Life is like a game

John Horton Conway claims that he did not work a day in his life. This excerpt from the biography of “Genius behind the Game” shows what serious mathematical theories, like surreal numbers, can appear from entertainment and games.

Gnawing the index finger of his left hand with his old broken British teeth, with swollen senile veins, with the eyebrow frowning thoughtfully under his long uncut hair, the mathematician John Horton Conway wastes his time without thinking about theoretical research. Although he will argue that he is not engaged in anything, he is lazy and plays toys.

')

He works at Princeton, although he gained fame at Cambridge (being first a student and then a professor from 1957 to 1987). Conway, 77, claims to have not worked a single day in his life. He means he spends almost all his time playing games. And at the same time, he is a professor at Princeton in Applied and Computational Mathematics (now honorary). Member of the Royal Community. And a recognized genius. “The title of genius is often misused,” says Percy Diaconis, a Stanford mathematician. - John Conway is a genius. At the same time it can work in any area. And he has a scent on all sorts of unusual things. It cannot be put in any mathematical framework. "

Princeton's haughty atmosphere is not quite suitable as a base for such a playful person. The buildings are built in the Gothic style and covered with ivy. In this environment, well-groomed aesthetics do not look old-fashioned. And in contrast, Conway is a hard-nosed, always with a mysterious face mine, a cross between Bilbo Baggins and Gandalf. Usually it can be found hanging around the department of mathematics on the third floor in a common room. The department is located in the 13-storey building of the Fine Hall, the tallest building of Princeton, on the roof of which are the towers of the operators Sprint and AT & T. And inside the number of professors is approximately equal to the number of students. Usually in a student’s company, Conway sits either on one of the couches in the common room, or in an alcove by the window in the hallway in one of two chairs looking at the board. From there, Conway turns to his familiar guest, quoting Shakespeare with Liverpool's usual liveliness:

(paraphrase from the comedy “How you will like it”: “Here is a poor virgin, a duke, a nondescript thing, a duke, but actually owned by me”).

Conway's contribution to mathematics includes countless games. Most of all, he is known as the inventor of the game "Life" in the late 1960s. Martin Gardner, who led a column in Scientific American, called her "Conway's most famous brainchild of the mind." This is a game about a cellular automaton - a machine with groups of cells that evolves in steps in discrete time. Cells transform, change shape and evolve into something else. “Life” is played on a lattice, where the cells resemble microorganisms viewed under a microscope.

Rules of the game

Strictly speaking, this is not really a game. Conway calls it "an endless game without a player." Musician and composer Brian Eno recalls that when he once saw a demonstration of this game on the monitor of the Exploratorium Museum in San Francisco, he experienced an "intuitive shock." “The whole system is so transparent that it shouldn’t bring surprises,” says Eno. “But there are enough surprises there - the complexity and organic nature of the evolution of point forms completely surpasses predictions.” And, as said by the announcer in one of the episodes of the Stephen Hawking television show Grand Design: “It is quite possible to imagine that something like the game“ Life ”with a few simple laws can reproduce quite complex things, and maybe even intelligence. This may require a grid of millions of squares, but this will not be surprising. There are hundreds of billions of cells in our brains. ”

"Life" became the first cellular automaton, and remains the most famous. The game led to the fact that cellular automata and similar simulations began to be used in complex sciences, where they simulate the behavior of anything, from ants to traffic jams, from clouds to galaxies. And it has become a classic for those who love to spend time aimlessly. The spectacle of groups of cells of the game, modified on the computer screen, turned out to be dangerous addictive students in mathematics, physics and computer science, like all people who had access to computers. In one of the military reports of the US Army, it was claimed that the hours spent watching the game “Life” cost the government millions of dollars. Well, at least, so says the legend. They also say that when in the mid-70s the game quickly began to gain popularity, it worked on a quarter of all computers in the world.

Overview of life forms that can be found in the game / from a letter to Martin Gardner [clickable]

When vanity rolls in on Conway (and this happens often), he opens up some new book on mathematics, finds an alphabetical index, and is annoyed that his name is most often quoted only in connection with the game "Life." And besides her a huge number of his ideas, which expanded mathematics, is very diverse. For example, his first love is geometry, and as a result, symmetry. He stood out by discovering something called the “Conway Constellation” - three sporadic groups in the family of such groups in the ocean of mathematical symmetry. The largest group is based on the Lich lattice, which is the most dense packing of spheres in a 24-dimensional space, where each sphere is in contact with 196560 other spheres. He also shed light on the largest sporadic group, the Fisher-Gris monster, in the Monstrous Moonshine hypothesis. And his biggest achievement, at least in his own opinion, is the discovery of a new type of numbers, called "surreal numbers." This is a continuum of numbers, including all real numbers (integers, fractional, irrational), and in addition to them all infinity, infinitely small values, etc. Surreal numbers, by his definition, are “endless classes of strange numbers never seen before by man”. Perhaps they will be able to describe everything, from infinite cosmos to infinitely small quantum quantities.

But the most amazing thing is how Conway stumbled upon them: playing and analyzing games. As in the Escher mosaic, where the birds turn into fish. Concentrate on white and you will see birds. Concentrate on red and you will see fish. Conway was watching a go-type game, and saw something else in it — numbers. And when he saw these numbers, he was impressed for several weeks.

In his best days in Cambridge in the 1970s, Conway, always in sandals, at any time of the year, entering the common room of the department of mathematics, usually announced his arrival with a loud bang on one of the beams in the center of the room. And this action was given to the bell. Ringing meant the beginning of a new day of games. Particularly interesting was one of the games, fatball (Phutball, AKA philosophical football).

Conway invented this game, but he doesn’t play it very well.

In fact, the futbol rules allow a player who has made a very bad move to ask “can I cry?”, And if he is allowed, he takes a turn back and replays. But even in this case, Conway fails to play this game well, and in general he doesn’t play particularly well in any games — at least he doesn’t win very often. Nevertheless, he participated in an endless number of games in the common room, raising them to a level worthy of serious scientific research. But at the same time, he sometimes allowed himself to suddenly jump up, grabbed a pipe under the ceiling and swayed back and forth on it.

These performances did not make him the main acrobat of the department. Then Frank Adams bypassed him, a topologist who was keen on mountaineering, who loved to crawl under the table, without touching the floor. Conway found him frightening, impossibly serious mathematician. A professor of astronomy and geometry, Adams had a reputation as a person who is hard to please, whose lectures are difficult to listen to - and a person who was strictly personal. Colleagues believed that his ambition was based on his periodic nervous breakdowns. Adams worked like he was obsessed, and that was worrying Conway. He was sure that Adams did not approve of his passive relaxed manner. And this made Conway feel guilty and think that he should be fired - and he was thinking about his wife and the ever-increasing group of his daughters who needed to be kept.

He married Eileen Howie, a teacher of French and Italian, in 1961. “He was an unusual young man, which attracted me,” she says. “John and I soon went to the restaurant after our acquaintance, and I stood, waited for him to open the door for me.” And he told me - well, come on, that you are standing! Most of the young people opened the doors, pushed the chairs, and so on. But it did not occur to him. He thought differently. Here is the door, you are standing in front of her, why not open it? Perhaps there is logic in this. ”

After marriage, they had four daughters, with periods of one, two, and three years. Conway remembered their birth years as the 1960th plus Fibonacci numbers: 1960 + 2, 3, 5, 8 = 1962, 1963, 1965, 1968.

And Conway knowingly worried about the possibility of losing his job. By 1968, he had achieved little. All he did was play games in the common room, invent and re-invent the rules of games that he found boring.

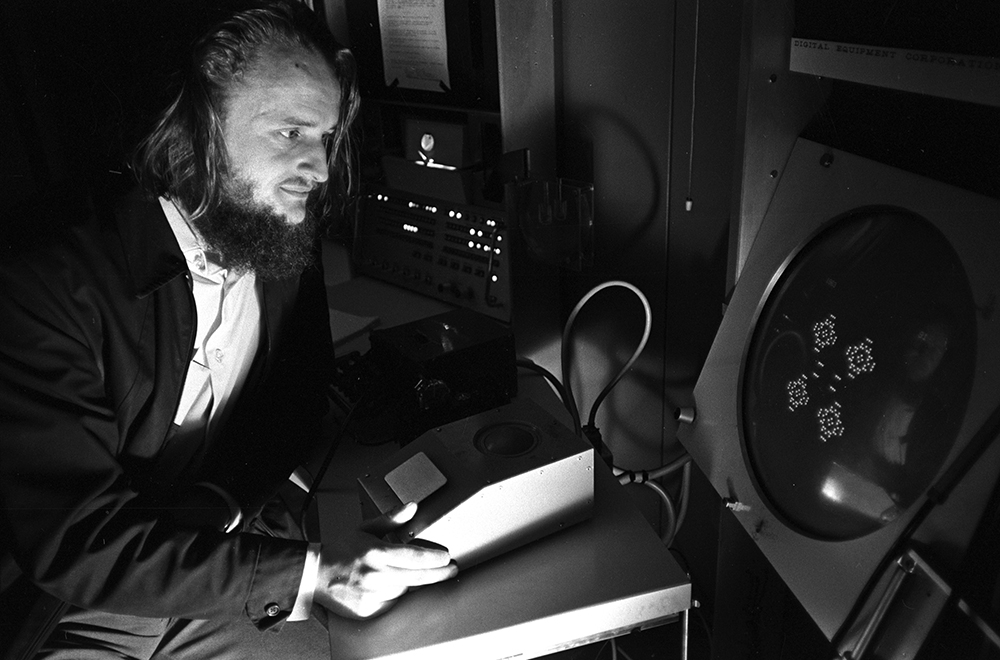

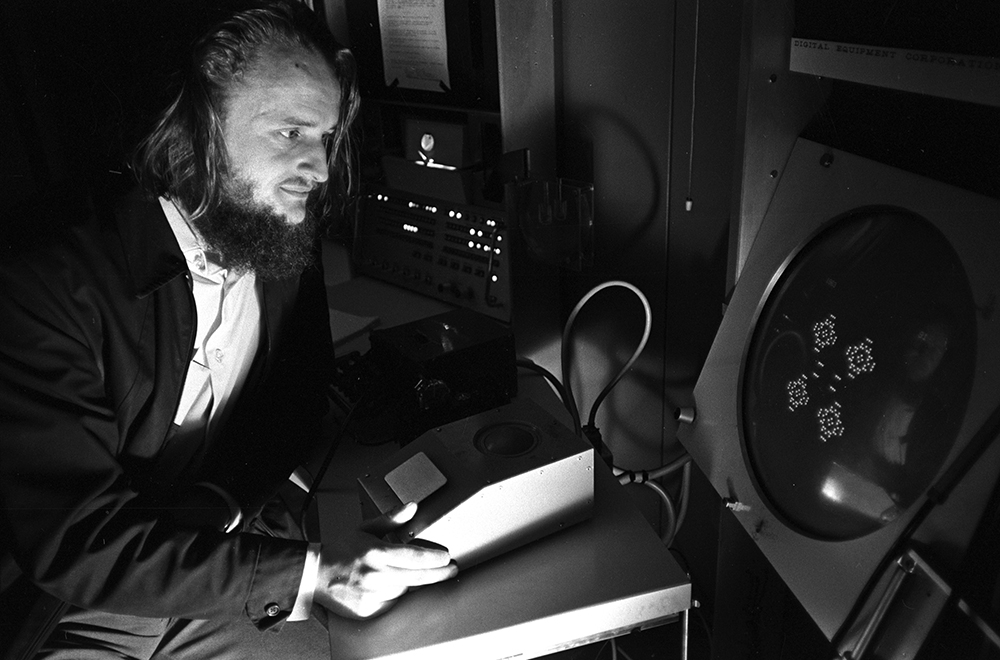

Conway plays Life in 1974

Conway liked the game, in which there are physical moves. He constantly played backgammon for small stakes (money, chalk, just for interest). At the same time, he did not reach the heights in this game. He often took risks, took doubles when this should not have been done, and raised the stakes up to 64 times the original, just to see what happens. And he constantly talked about mathematics. For example, “Conway’s piano problem”, which asks: what is the largest object that can be moved beyond a rectangular corner in a corridor of fixed width?

He was not so interested in winning backgammon, as it is interesting to explore the possibilities in the game. He liked to play specially, staying in the tail with the worst players. His rivals often lost their vigilance and began to lose. And then he made his move. Usually this strategy did not work. But sometimes he was lucky (randomness is an element of the game of backgammon, and therefore it does not lend itself to rigorous scientific analysis), and then he would make a dizzying victory.

While Conway was addicted to backgammon, his other colleagues were afraid to play them for a long time, while others refused altogether, fearing that they would get involved in the game and their research would be abandoned. Others have argued that Conway is a bad example for students. But this was his plan.

One of the students was Simon Norton, a wunderkind who attended Eton College and received a degree from the University of London while he was in the last grade of high school. Arriving in Cambridge, and already an experienced backgammon player, Norton fit into the company easily. He was able to perform calculations very quickly in his mind, and became Conway’s protege, solving problems for him that he could not solve. He watched all the tasks that were solved by everyone and everybody, spied, listened, interrupted anyone with shouts of “not true!” When he noticed a mistake in him. He also had an impressive vocabulary that Conway liked. He was known for his ability to solve anagrams. For example, one day someone shouted an anagram of "phoneboxes". Even before anyone had time to raise his head and understand what was happening, Norton proclaimed: "Xenophobes!".

Mostly Conway played silly kids' games - Dots and Boxes, Fox and Geese, and sometimes he played them with children, mostly with his four daughters. And, of course, with his minions - often in the games that they invented in order to please their leader. Colin Vout came up with the game COL, and Simon Norton - SNORT, and both games consisted in coloring areas. Norton also invented the game of Tribulations, and Mike Guy parried, giving out Fibulations - both games similar to them, one based on triangular numbers, and the other on Fibonacci numbers. Conway came up with Sylver Coinage, in which two players took turns to call different positive integers, but they could not name the number, which was the sum of any of the previously mentioned numbers. The first player who called the unit lost.

Many games are included in Winning Ways for Your Mathematical Plays, written by Conway and two co-authors, Elvin Berlekamp, a mathematician from the University of California, and Richard Guy from the University of Calgary.

The trinity of the pioneers of game theory came together at the conference "Computers in Number Theory" in 1969. Conway - in the third row from the top, second from the right (with a beard). Alvin Berlekamp - fourth row from the top, sixth from the right (also with a beard). Richard Guy - fourth row from the top, ninth from the left (with a striped tie). [clickable]

It took 15 years to write a book, partly because Conway and Guy loved working out this nonsense and spent their time on Berlekamp. He called them "a couple of boobies." And, nevertheless, the book has become a bestseller, despite the fact that the need to print in color and in unusual fonts has taken away so much money that they have almost no advertising. The book was a tutorial on how to win games. The authors poured out theories into it, like from a horn of plenty, and added many new games suitable for their theoretical research.

Conway wrote:

So they scored games without titles, and titles without games.

Sometimes Conway went to visit Martin Gardner, and they exchanged materials on mathematical entertainment. It wasn’t necessarily a game — it could be jigsaw puzzles, and other entertainment for the Nirds. Take, for example, the Doomsday Algorithm, which allowed us to determine the day of the week for any date. And although he demonstrated this trick since adolescence, the algorithm came up during a visit to Gardner. Conway flew to New York and waited for his friend to pick him up from the airport. He waited, and waited ... But Gardner still did not appear.

Gardner was late for more than two hours, ran into the airport lounge, waving his arms wildly, with apologies and promises: "You will forgive me as soon as you find out what I have found!" He was in the public library of New York, where he found a note published in 1887 in the journal Nature: "How to know the day of the week for any date." Article written by Lewis Carroll. He wrote: “Stumbling on the next method of calculating in the mind of the day of the week for any chosen date, I send it to you, hoping that it will interest any of your readers. I myself do not think very quickly, and it usually takes me to this counting of seconds for 20. But I think that it may take less than 15 seconds for a quickly counting person. ”

Gardner could not deny himself in the manufacture of photocopies of the notes, but there was a long queue to the copy machine. He got into her, but she moved very slowly. By the time it became clear that he was late in taking Conway, he had already stood for 30 minutes, and decided that another 15 minutes would be enough for him. He thought it was worth it, and he knew that Conway would agree with him.

ending

PS: calculating the day of the week in the mind of the habruiser Danov

Gnawing the index finger of his left hand with his old broken British teeth, with swollen senile veins, with the eyebrow frowning thoughtfully under his long uncut hair, the mathematician John Horton Conway wastes his time without thinking about theoretical research. Although he will argue that he is not engaged in anything, he is lazy and plays toys.

')

He works at Princeton, although he gained fame at Cambridge (being first a student and then a professor from 1957 to 1987). Conway, 77, claims to have not worked a single day in his life. He means he spends almost all his time playing games. And at the same time, he is a professor at Princeton in Applied and Computational Mathematics (now honorary). Member of the Royal Community. And a recognized genius. “The title of genius is often misused,” says Percy Diaconis, a Stanford mathematician. - John Conway is a genius. At the same time it can work in any area. And he has a scent on all sorts of unusual things. It cannot be put in any mathematical framework. "

Princeton's haughty atmosphere is not quite suitable as a base for such a playful person. The buildings are built in the Gothic style and covered with ivy. In this environment, well-groomed aesthetics do not look old-fashioned. And in contrast, Conway is a hard-nosed, always with a mysterious face mine, a cross between Bilbo Baggins and Gandalf. Usually it can be found hanging around the department of mathematics on the third floor in a common room. The department is located in the 13-storey building of the Fine Hall, the tallest building of Princeton, on the roof of which are the towers of the operators Sprint and AT & T. And inside the number of professors is approximately equal to the number of students. Usually in a student’s company, Conway sits either on one of the couches in the common room, or in an alcove by the window in the hallway in one of two chairs looking at the board. From there, Conway turns to his familiar guest, quoting Shakespeare with Liverpool's usual liveliness:

Welcome! Mine but mine own!

(paraphrase from the comedy “How you will like it”: “Here is a poor virgin, a duke, a nondescript thing, a duke, but actually owned by me”).

Conway's contribution to mathematics includes countless games. Most of all, he is known as the inventor of the game "Life" in the late 1960s. Martin Gardner, who led a column in Scientific American, called her "Conway's most famous brainchild of the mind." This is a game about a cellular automaton - a machine with groups of cells that evolves in steps in discrete time. Cells transform, change shape and evolve into something else. “Life” is played on a lattice, where the cells resemble microorganisms viewed under a microscope.

Rules of the game

Strictly speaking, this is not really a game. Conway calls it "an endless game without a player." Musician and composer Brian Eno recalls that when he once saw a demonstration of this game on the monitor of the Exploratorium Museum in San Francisco, he experienced an "intuitive shock." “The whole system is so transparent that it shouldn’t bring surprises,” says Eno. “But there are enough surprises there - the complexity and organic nature of the evolution of point forms completely surpasses predictions.” And, as said by the announcer in one of the episodes of the Stephen Hawking television show Grand Design: “It is quite possible to imagine that something like the game“ Life ”with a few simple laws can reproduce quite complex things, and maybe even intelligence. This may require a grid of millions of squares, but this will not be surprising. There are hundreds of billions of cells in our brains. ”

"Life" became the first cellular automaton, and remains the most famous. The game led to the fact that cellular automata and similar simulations began to be used in complex sciences, where they simulate the behavior of anything, from ants to traffic jams, from clouds to galaxies. And it has become a classic for those who love to spend time aimlessly. The spectacle of groups of cells of the game, modified on the computer screen, turned out to be dangerous addictive students in mathematics, physics and computer science, like all people who had access to computers. In one of the military reports of the US Army, it was claimed that the hours spent watching the game “Life” cost the government millions of dollars. Well, at least, so says the legend. They also say that when in the mid-70s the game quickly began to gain popularity, it worked on a quarter of all computers in the world.

Overview of life forms that can be found in the game / from a letter to Martin Gardner [clickable]

When vanity rolls in on Conway (and this happens often), he opens up some new book on mathematics, finds an alphabetical index, and is annoyed that his name is most often quoted only in connection with the game "Life." And besides her a huge number of his ideas, which expanded mathematics, is very diverse. For example, his first love is geometry, and as a result, symmetry. He stood out by discovering something called the “Conway Constellation” - three sporadic groups in the family of such groups in the ocean of mathematical symmetry. The largest group is based on the Lich lattice, which is the most dense packing of spheres in a 24-dimensional space, where each sphere is in contact with 196560 other spheres. He also shed light on the largest sporadic group, the Fisher-Gris monster, in the Monstrous Moonshine hypothesis. And his biggest achievement, at least in his own opinion, is the discovery of a new type of numbers, called "surreal numbers." This is a continuum of numbers, including all real numbers (integers, fractional, irrational), and in addition to them all infinity, infinitely small values, etc. Surreal numbers, by his definition, are “endless classes of strange numbers never seen before by man”. Perhaps they will be able to describe everything, from infinite cosmos to infinitely small quantum quantities.

But the most amazing thing is how Conway stumbled upon them: playing and analyzing games. As in the Escher mosaic, where the birds turn into fish. Concentrate on white and you will see birds. Concentrate on red and you will see fish. Conway was watching a go-type game, and saw something else in it — numbers. And when he saw these numbers, he was impressed for several weeks.

In his best days in Cambridge in the 1970s, Conway, always in sandals, at any time of the year, entering the common room of the department of mathematics, usually announced his arrival with a loud bang on one of the beams in the center of the room. And this action was given to the bell. Ringing meant the beginning of a new day of games. Particularly interesting was one of the games, fatball (Phutball, AKA philosophical football).

Fatball rules

The game begins with a single chip (“ball”), which is located on the central cross of a square grid - for example, for the game of go. Two players sit on opposite sides of the board and take turns. At each turn, the player can either put one white chip (“man”) at any free intersection, or perform a jump sequence.

To jump the ball must be near one or more people. It moves in a straight line (vertical, horizontal or diagonal) at the first free intersection behind the person. The person who jumped is removed from the field. If a jump is made, the same player can jump further, all the time while the ball is near at least one person - or he can stop the move at any time. Jumping is optional - you can instead place a person on the field.

The game ends when the sequence of jumps ends on the edge or behind the edge of the board closest to the opponent (“goal”), in which case the one who made the jumps wins. A series of jumps can take place exactly along the opponent's goal line, without going behind it. One of the interesting properties of a fatball is that every player can be played by any player.

Conway invented this game, but he doesn’t play it very well.

In fact, the futbol rules allow a player who has made a very bad move to ask “can I cry?”, And if he is allowed, he takes a turn back and replays. But even in this case, Conway fails to play this game well, and in general he doesn’t play particularly well in any games — at least he doesn’t win very often. Nevertheless, he participated in an endless number of games in the common room, raising them to a level worthy of serious scientific research. But at the same time, he sometimes allowed himself to suddenly jump up, grabbed a pipe under the ceiling and swayed back and forth on it.

These performances did not make him the main acrobat of the department. Then Frank Adams bypassed him, a topologist who was keen on mountaineering, who loved to crawl under the table, without touching the floor. Conway found him frightening, impossibly serious mathematician. A professor of astronomy and geometry, Adams had a reputation as a person who is hard to please, whose lectures are difficult to listen to - and a person who was strictly personal. Colleagues believed that his ambition was based on his periodic nervous breakdowns. Adams worked like he was obsessed, and that was worrying Conway. He was sure that Adams did not approve of his passive relaxed manner. And this made Conway feel guilty and think that he should be fired - and he was thinking about his wife and the ever-increasing group of his daughters who needed to be kept.

He married Eileen Howie, a teacher of French and Italian, in 1961. “He was an unusual young man, which attracted me,” she says. “John and I soon went to the restaurant after our acquaintance, and I stood, waited for him to open the door for me.” And he told me - well, come on, that you are standing! Most of the young people opened the doors, pushed the chairs, and so on. But it did not occur to him. He thought differently. Here is the door, you are standing in front of her, why not open it? Perhaps there is logic in this. ”

After marriage, they had four daughters, with periods of one, two, and three years. Conway remembered their birth years as the 1960th plus Fibonacci numbers: 1960 + 2, 3, 5, 8 = 1962, 1963, 1965, 1968.

And Conway knowingly worried about the possibility of losing his job. By 1968, he had achieved little. All he did was play games in the common room, invent and re-invent the rules of games that he found boring.

Conway plays Life in 1974

Conway liked the game, in which there are physical moves. He constantly played backgammon for small stakes (money, chalk, just for interest). At the same time, he did not reach the heights in this game. He often took risks, took doubles when this should not have been done, and raised the stakes up to 64 times the original, just to see what happens. And he constantly talked about mathematics. For example, “Conway’s piano problem”, which asks: what is the largest object that can be moved beyond a rectangular corner in a corridor of fixed width?

He was not so interested in winning backgammon, as it is interesting to explore the possibilities in the game. He liked to play specially, staying in the tail with the worst players. His rivals often lost their vigilance and began to lose. And then he made his move. Usually this strategy did not work. But sometimes he was lucky (randomness is an element of the game of backgammon, and therefore it does not lend itself to rigorous scientific analysis), and then he would make a dizzying victory.

While Conway was addicted to backgammon, his other colleagues were afraid to play them for a long time, while others refused altogether, fearing that they would get involved in the game and their research would be abandoned. Others have argued that Conway is a bad example for students. But this was his plan.

One of the students was Simon Norton, a wunderkind who attended Eton College and received a degree from the University of London while he was in the last grade of high school. Arriving in Cambridge, and already an experienced backgammon player, Norton fit into the company easily. He was able to perform calculations very quickly in his mind, and became Conway’s protege, solving problems for him that he could not solve. He watched all the tasks that were solved by everyone and everybody, spied, listened, interrupted anyone with shouts of “not true!” When he noticed a mistake in him. He also had an impressive vocabulary that Conway liked. He was known for his ability to solve anagrams. For example, one day someone shouted an anagram of "phoneboxes". Even before anyone had time to raise his head and understand what was happening, Norton proclaimed: "Xenophobes!".

Mostly Conway played silly kids' games - Dots and Boxes, Fox and Geese, and sometimes he played them with children, mostly with his four daughters. And, of course, with his minions - often in the games that they invented in order to please their leader. Colin Vout came up with the game COL, and Simon Norton - SNORT, and both games consisted in coloring areas. Norton also invented the game of Tribulations, and Mike Guy parried, giving out Fibulations - both games similar to them, one based on triangular numbers, and the other on Fibonacci numbers. Conway came up with Sylver Coinage, in which two players took turns to call different positive integers, but they could not name the number, which was the sum of any of the previously mentioned numbers. The first player who called the unit lost.

Many games are included in Winning Ways for Your Mathematical Plays, written by Conway and two co-authors, Elvin Berlekamp, a mathematician from the University of California, and Richard Guy from the University of Calgary.

The trinity of the pioneers of game theory came together at the conference "Computers in Number Theory" in 1969. Conway - in the third row from the top, second from the right (with a beard). Alvin Berlekamp - fourth row from the top, sixth from the right (also with a beard). Richard Guy - fourth row from the top, ninth from the left (with a striped tie). [clickable]

It took 15 years to write a book, partly because Conway and Guy loved working out this nonsense and spent their time on Berlekamp. He called them "a couple of boobies." And, nevertheless, the book has become a bestseller, despite the fact that the need to print in color and in unusual fonts has taken away so much money that they have almost no advertising. The book was a tutorial on how to win games. The authors poured out theories into it, like from a horn of plenty, and added many new games suitable for their theoretical research.

Conway wrote:

We invented a new game in the morning in order to serve as an application of our theory. And after half an hour of research, it turned out to be nonsense. Therefore, we have invented another. In a working day ten times for half an hour, roughly speaking, and therefore we invented 10 games a day. We examined them, sifted them, and about one out of ten turned out to be good enough to be included in the book.

So they scored games without titles, and titles without games.

We had a “marriage problem.” We invented the game, and if it was good, then there was a problem to somehow call it. If the name was not thought out, we put it in the folder “games without a name.” And then scrupulous and loving accuracy Richad started another folder, “titles without games.” All attempts to invent a name for the game ended with the invention of heaps of different names that did not fit the desired game well, but were not bad in themselves. Therefore, they were sent to the folder "titles without games." Each of the folders grew, and we rarely managed to “marry” between two records of each other.

I remember the best name without the game. It sounds like "do not call us, we will call you" (Don't Ring Us, We'll Ring You; ring - "call", and also - "ring", or "circle around the ring"). We did not reach out to the invention of the game, but the essence of it is completely clear: the players would draw something on paper, and the goal would be to circle the opponent. For such a game, it would be a great name. But the game itself, we have not come up with.

Sometimes Conway went to visit Martin Gardner, and they exchanged materials on mathematical entertainment. It wasn’t necessarily a game — it could be jigsaw puzzles, and other entertainment for the Nirds. Take, for example, the Doomsday Algorithm, which allowed us to determine the day of the week for any date. And although he demonstrated this trick since adolescence, the algorithm came up during a visit to Gardner. Conway flew to New York and waited for his friend to pick him up from the airport. He waited, and waited ... But Gardner still did not appear.

At first I thought, okay, it will appear in five minutes. But I waited there for a very long time - I don’t know, maybe a whole hour. And I began to think: "What if he does not appear?". I didn't even have his phone. And even if I did, I did not know how to make a phone call in America. Therefore, I could only sit there and hope.

Gardner was late for more than two hours, ran into the airport lounge, waving his arms wildly, with apologies and promises: "You will forgive me as soon as you find out what I have found!" He was in the public library of New York, where he found a note published in 1887 in the journal Nature: "How to know the day of the week for any date." Article written by Lewis Carroll. He wrote: “Stumbling on the next method of calculating in the mind of the day of the week for any chosen date, I send it to you, hoping that it will interest any of your readers. I myself do not think very quickly, and it usually takes me to this counting of seconds for 20. But I think that it may take less than 15 seconds for a quickly counting person. ”

Gardner could not deny himself in the manufacture of photocopies of the notes, but there was a long queue to the copy machine. He got into her, but she moved very slowly. By the time it became clear that he was late in taking Conway, he had already stood for 30 minutes, and decided that another 15 minutes would be enough for him. He thought it was worth it, and he knew that Conway would agree with him.

ending

PS: calculating the day of the week in the mind of the habruiser Danov

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/274081/

All Articles