War, peace and ABBYY Compreno: the continuation of our affair with Tolstoy

Recently we talked here about how the project “All Tolstoy was done in one click” . With the help of 3249 (three thousand two hundred forty nine) volunteers and 1 (one) good OCR technology, we digitized 46,820 pages of the writer's 90-volume collected works, carefully subtracted them and put them in public access .

Recently we talked here about how the project “All Tolstoy was done in one click” . With the help of 3249 (three thousand two hundred forty nine) volunteers and 1 (one) good OCR technology, we digitized 46,820 pages of the writer's 90-volume collected works, carefully subtracted them and put them in public access .But if you thought that our “affair with Tolstoy” was over, then you were wrong - digitizing the writer's texts, we began to investigate them with the help of ABBYY Compreno information retrieval technology - do not perish such rich material. That has given us "text mining of Tolstoy" and where the obtained results are now used, read on.

Introduction

The main goal of the project “All Tolstoy in one click” was to make Tolstoy’s work truly universal property, so that all texts that came out of his pen were available in one click anywhere in the world. As, by the way, the author himself bequeathed, even during his lifetime, he refused all rights to his texts (yes, anonymus, Leo Tolstoy knew about copyleft and opendat long before these of your Internet and Richard Stallman).

')

However, the ability to download a book in a convenient format into a reader or tablet is not the only plus of digitization. Now the texts of Tolstoy can not only be read, but also “measured”, that is, explored using different quantitative methods, using the entire arsenal of automatic text processing tools (AOT, also known as NLP). After all, if you have all the texts of a writer in electronic form, even with the help of one or two competent search queries, you can get curious data that some literary critic could have spent weeks and months of hard work at other times. And if you also have an advanced technology of natural language analysis , then there are chances to make a serious philological discovery (even without being a philologist). Below, I will tell you what we managed to intend and learn to us, but before that - a few words about who, how and why, is engaged in the automatic processing of literary texts and what interesting things can happen.

Lyrical digression: Distant Reading and Computational Philology

In 2010, Google counted 130 million books in the world, and this statistic was attributed “at least until Sunday”. Today there are probably several million more. In itself, this is not a problem - and so it is clear that reading “everything about everything” is a bad idea

A possible (albeit controversial) solution to this problem was one of the first proposed by the shocking critic and former neo-Marxist Franco Moretti, who now heads the Stanford Literary Lab. He said that literary scholars today should "stop reading books and start counting, mapping and visualizing them." Moretti contrasts reading to “distant reading”, that is, automatic analysis of text boxes, counting statistics, graphing, and so on. In his opinion, only in this way can we make literary criticism “objective” and avoid conclusions drawn from the “ridiculously small” sample. The research results of the Stanford Literary Lab, performed in the spirit of “distant reading”, can be found here .

“Remote Reading” with Compreno

Researchers from Stanford mainly use the simplest statistics - for example, the frequency of words and N-grams and their distribution in the text. From the very beginning, we decided to explore such aspects of a literary text that cannot be pulled out with a simple Ctrl + F. For example, the speech activity of the characters: try to immediately calculate how many times Natasha Rostova (or any other character) says something. Pretty quickly, you will realize that for this, first of all, it would be nice to be able to automatically resolve the pronominal anaphor (for examples like “ Natasha began to wear a dress. - Now, now, don't go, dad,” she called out to her father ” ). second, to somehow limit the set of verbs that can express the fact of “speaking” (and they are quite diverse), and thirdly, to have at least an automatic morphology, and even better syntax (since word order is free, and not so easy to find a speaker in examples like " He never blessed his of their children and only, having substituted her with a bristly, still unshaven cheek, he said strictly and at the same time attentively and tenderly looking at her: “Healthy? .. well, then sit down! ”).

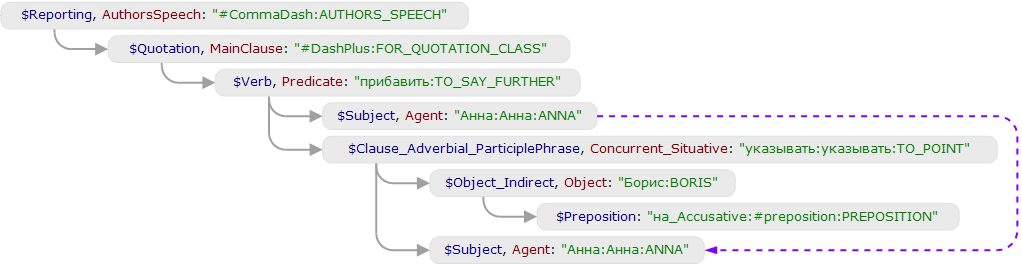

Fortunately, all this is already “wired” in Compreno. The syntactic-semantic trees that the parser issues contain all the necessary information about who said what and how, they have already removed syntactic and lexical homonymy and allowed the pronoun anaphora. For example, in such a fragment “ Really? - exclaimed Anna Mikhailovna. - Oh, it's terrible! It is terrible to think ... This is my son, - she added, pointing to Boris. “He himself wanted to thank you. ” You need to understand who she is, and correctly add the semantic class of a multi-valued verb to add. Compreno copes with both tasks - this is how the subtree looks like for “ she added, pointing to Boris ”:

To get from these trees mentions of characters and the necessary information about them allows our mechanism for extracting information, which we have more than once described here from different sides ( one , two ). By relying on the deep syntax and semantic hierarchy, we can cover a large class of cases with 1-2 tree patterns. For example, the rule that looks for this structure:

will work on such different examples as:

- Do you want to kiss me? She whispered, barely audibly, looking at him from under her brows, smiling and almost crying with emotion.

Denisov, don't you joke with this, - shouted Rostov , - this is such a high, such a wonderful feeling, such ...

Hush, hush, can't you hush? - apparently more suffering than the dying soldier, said the sovereign and drove off.

The aunt cleared her throat, swallowed drooling and said in French that she was very glad to see Helene;

In addition to speech activity, we explored several other aspects of the behavior of Tolstoy’s heroes. Below I will talk about what we managed to find out.

Impulsive Natasha Rostova and the imperturbable Andrei Bolkonsky: what did you manage to understand with the help of Compreno

To begin with, we simply calculated how many times each character of “War and Peace” makes a statement, and made up the top of the most “talkative” characters in absolute numbers. Those who are familiar with the content of the novel, he is unlikely to be surprised:

Here, the frequency, apparently, is nothing more than an indicator of the "centrality" of the character.

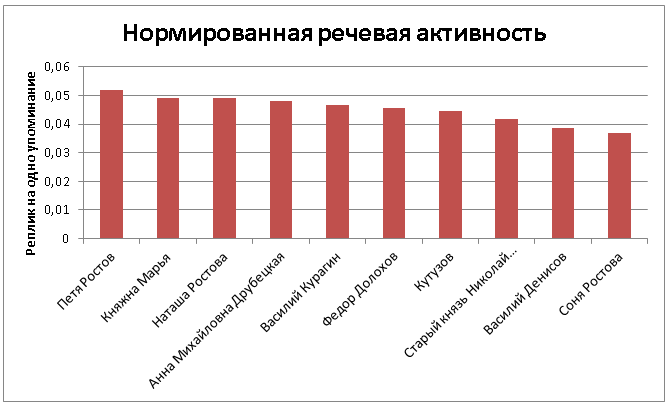

If we normalize the figures obtained to the total number of mentions in the text (after removing too low-frequency heroes), our top changes noticeably:

Now Petya Rostov is upstairs - an emotional and talkative child in the first volume, a young enthusiastic romantic teenager - in the fourth (up to his own death). Following are three female characters - Princess Marya, quiet, modest and exhausted by a strict father, which we learn mainly from conversations with other characters and an internal monologue, Natasha Rostova, an immediate and lively heroine, whose remarks the reader hears throughout the novel (in the first Tome is 13 years old, in the epilogue - 29), and Anna Drubetskaya, an active schemer who can sabotage any person she needs into submission.

It must be said here that Tolstoy considered it important to supply each character with his own style of speech - this was part of his creative method. Even his well-known dislike for Shakespeare (“the world recognized for brilliant works of art by Shakespeare's <...> were disgusting to me”) was explained by the fact that supposedly “Shakespeare lacks the main, if not the only means of portraying characters,“ language ”, then there is that each face speaks in its own way, its language. ” Therefore, in the next stage, we tried to identify some significant parameters, according to which the characters' speech can stably differ.

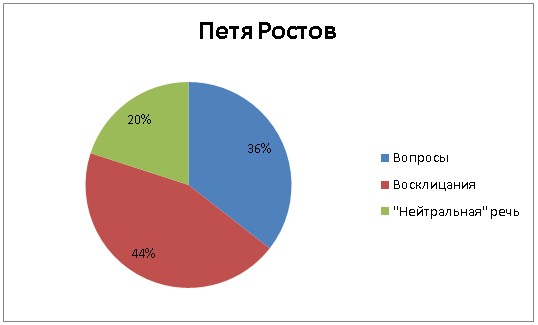

The first parameter that comes to mind is the number of exclamation and interrogative sentences. By the correlation of questions, exclamations and all other (conditionally neutral) speech, one can already understand quite a lot about the character. Let's compare three young Rostovs, Andrey Bolkonsky and Pierre Bezukhov. Predictable exclamation champion - the youngest of the Rostovs, Peter:

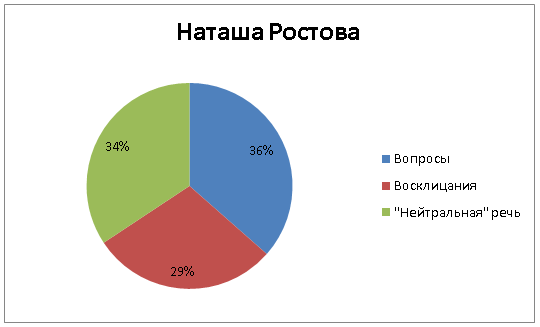

Natasha is older than Petit and shows a bit more restraint, but she still remains very emotional, only a third of her speech is conditionally “neutral”:

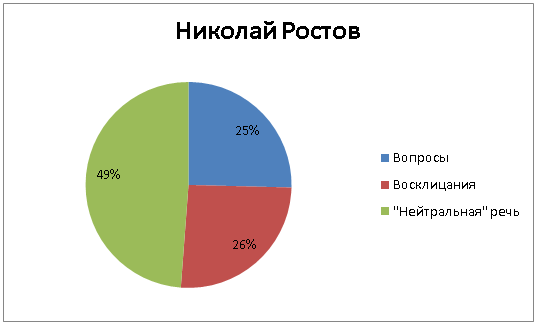

The elder brother of Petit and Natasha Nikolai exclaims and asks even less, but half of the share of neutral speech does not reach - like all the Rostovs, he is also very emotional:

Another thing is Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, immaculately seasoned, proud, belonging to a secular society with cold contempt and showing emotions only in a circle of close people (it was not for nothing that the strong-willed handsome Vyacheslav Stierlitz Tikhonov played in the Oscar-winning Soviet screen version). Bolkonsky exclaims very little, and he asks relatively little:

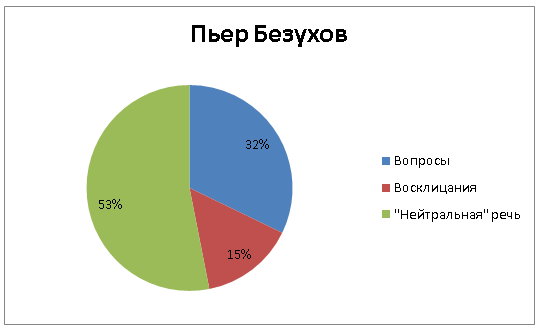

Pierre Bezukhov - perhaps the most reflective character of the novel. He is clearly more emotional than Andrei Bolkonsky, but not in the direction of "exclamations", like the whole Rostov family. Pierre exclaims rarely, but asks almost as often as Peter as a child with Natasha as a very childish person:

Also, with the help of Compreno, you can easily get the characteristic that Tolstoy gives to the act of speaking, and this too can act as a kind of parameter. Most often, such a characteristic is expressed in the form of deprivate turn attached to the verb of speaking ( Pierre shouted, with a decisive and drunken gesture striking the table ) or additions in the instrumental case with a preposition with ( asked Prince Vasili with more twitching of the cheeks than before ). For example, the speech of the rich, important and mercenary Prince Vasiliy Kuragin more often than in other characters is accompanied by impartial turnovers, in which either his appearance is characterized ( rubbing his bald head, straightening the jabot ), or hidden intentions, character traits, soul movements ( saying he didn’t want to be believed, angrily moving the table back to him ); Anna Mikhailovna Drubetskaya, always dabbling in front of the heroes, from whom she needs something, often says “smiling” or “with a smile”; in phlegmatic, constantly sleepy Kutuzov, speaking is often accompanied by a movement of the head: he now nods to her, then lowers her.

Sensitive Marya Bolkonskaya and intrigues around the legacy of Pierre: the deep syntax of "War and Peace"

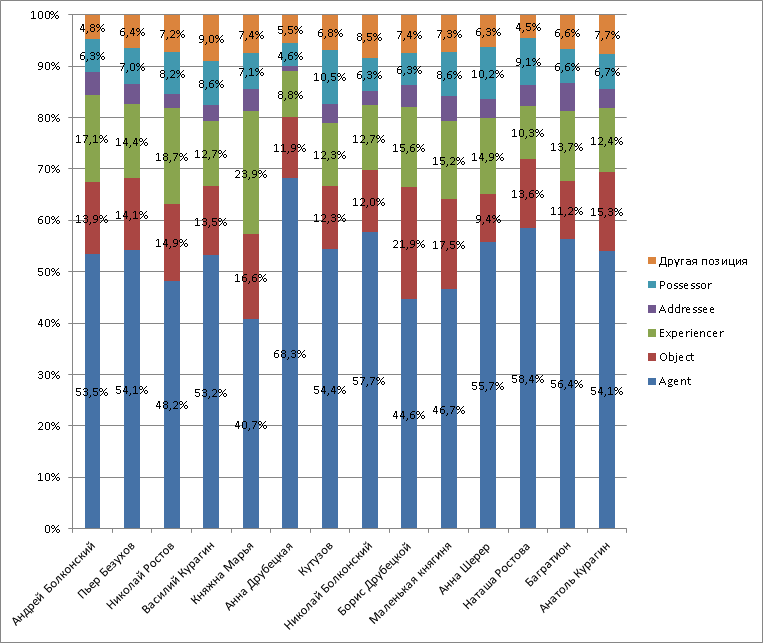

In our next micro-study, we decided not to limit ourselves to speech activity and consider all situations of the hero's “activity” in the text. To do this, we collected statistics on the deep positions in which the characters fall under various predicates. Depth positions in Compreno trees are similar to semantic roles : for example, if the hero performs an active action (says, goes, shoots, hits), he gets into the position of an agent (Agent); if he finds himself in the role of a passive object of external influence (he is scolded, driven, beaten, praised, loved), gets into the position of an object (Object), if he perceives, sees, hears, feels or, for example, likes something, he becomes an experimenter (Experiencer); if she acts as the addressee of the message ( she told Pierre ), she gets into the addressee position (Addressee). There are other positions (there are about 500 of them in our model), but here we use only a few of the most common ones that can appear under the predicate.

It is important that the deep positions reflect the semantic roles of the participant in the speech situation and do not directly depend on the specific implementation in the sentence. So, in the sentences Pierre loved Natasha and Natasha was loved by Pierre Pierre to be an experimenter, and Natasha was an object regardless of pledge.

It turned out that the statistics on the depth positions allows to get some information about the differences in the characters of the characters and gives an "objective" confirmation of the images that are formed in the reader during his acquaintance with the novel. Let's look at the diagram, where the shares of the chosen depth positions for the main characters in the first volume of “War and Peace” are presented:

In general, the frequency distributions look similar, and quite predictably, the most frequent position for all the characters turned out to be agent-based. However, the variation here is quite large - from 40.7% for Princess Mary and 44.6% for Boris Drubetskoy to 68.3% for Anna Drubetskoy. These three "extreme" characters are of interest.

Princess Marya is remarkable, first of all, by the anomalously high frequency of hitting the position of an experimenter. In combination with the low frequency of agent use, this gives us a portrait of a character that feels a lot, but has little effect, which is completely true for the first volume. Andrei Bolkonsky’s sister, along with his father, an old, pedantic and strict to tyranny Catherine’s general, “without a break” lives on an estate in Lysy Hills, spending time in correspondence with her brother and girlfriend Julie, communicating with the pilgrims and practicing the algebra and geometry that the old one arranges for her the prince. In the field of view of the reader, she appears solely in connection with the visits to the Bald Hills of other heroes. Literary scholars believe that the image of Princess Mary was created by Tolstoy under the strong influence of sentimentalism of the XVIII century.

The title of Anna Drubetskaya in terms of share of active use is also easily explained by the plot of the first volume. This elderly lady of a noble family, but of a very modest state at the beginning of the novel, develops a stormy activity, the ultimate goal of which is the well-being and promotion of her only son Boris. She is described as “one of those women, especially mothers, who, once having taken something in their heads, will not be left behind until they fulfill their desires, but are otherwise ready for daily, minutely molestation, and even scenes” . First, Anna Mikhailovna besieged the rich and influential Prince Vasily, seeking the transfer of his son to the guard, then successfully intrigues against him for the inheritance of Count Bezukhov, while at the same time earning money from the Rostovs to “dress Boris”.

Boris himself has not yet become as cynical, dexterous and greedy as his mother - this will happen in the following volumes. He does not want to step over his own pride, and therefore opposes the requests of Anna Mikhailovna to be "nice", "affectionate" and "attentive" during visits to important people and extremely reluctant to participate in her efforts, acting as a passive object. Boris's passivity is reflected in our graph by a large proportion of the object depth position.

Natasha's “fat neck” in your smartphone: liven up “War and Peace”

Attempts to "count" the literature often provoke criticism in the spirit that, they say, the authors try to measure the immeasurable and thereby vilify and emasculate the imperishable work of the classic. Interestingly, such accusations sounded 100 years ago, when there was no distant reading. “It was believed that to study the work itself is to anatomize it, and for this it is necessary, as is well known, to first kill a living being. We were constantly reproached for this crime, ”wrote Boris Eikhenbaum, one of the largest representatives of the formal method in literary criticism in 1921 (and the formalists of those times were something like people who invented distant reading in theory long before the invention of the computer and were unable to practice it).

In order not to accuse us of “murder” of the novel, we decided to do the exact opposite, that is, its revival. To this end, we, together with colleagues from the Higher School of Economics, have joined the development of the Samsung Living Pages mobile application, which now uses the results of the information extraction system based on ABBYY Compreno.

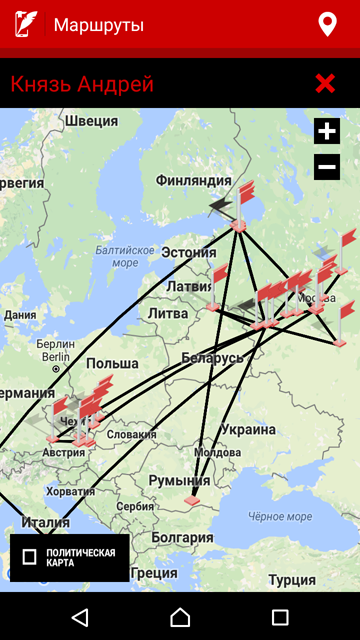

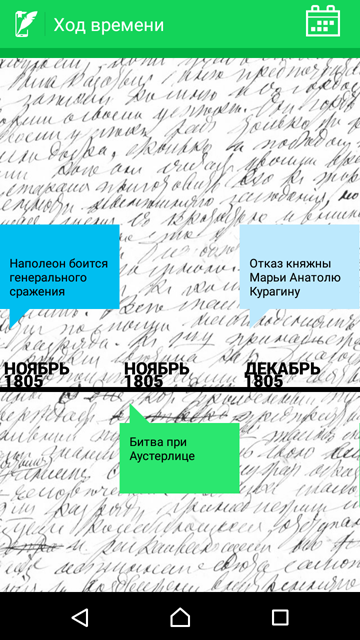

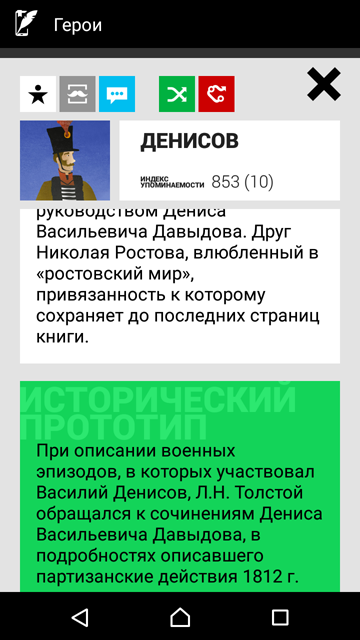

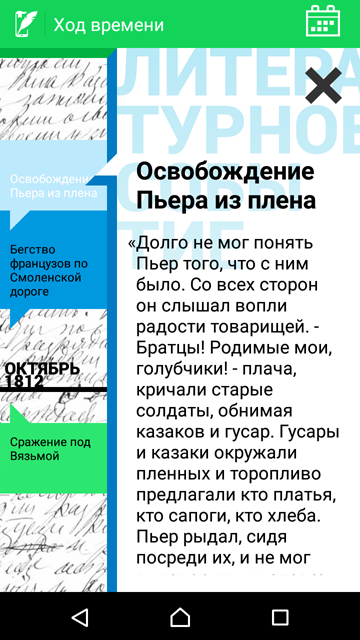

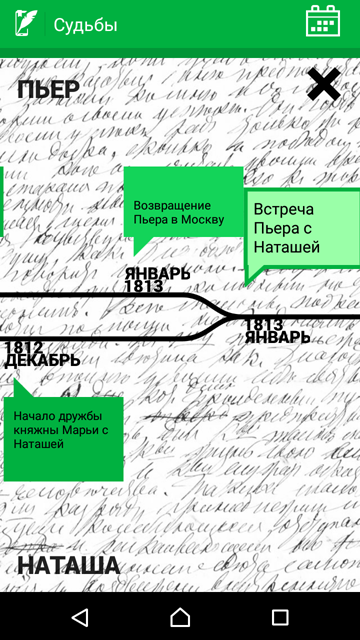

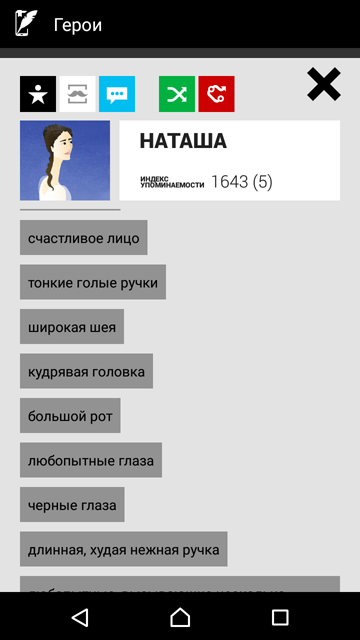

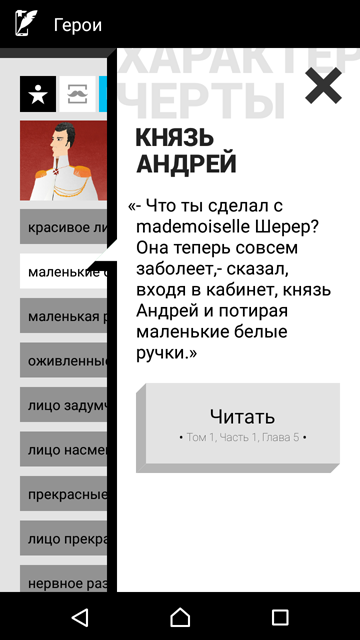

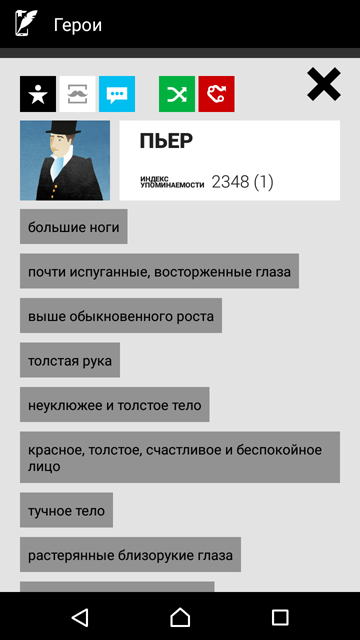

In the Live Pages application, several non-standard scenarios for acquaintance with works of art and their heroes are implemented: timelines with events and destinies, cards and character quotes, interactive maps with reference to places for episodes of the novel.

All this is based on infographics, made in the game style and, it seems to us, has more chances to hook a tenth-grader gadzhetoman with ADD than a thick volume that the school librarian will hand him.

In addition to the speech of characters for quotations, ompreno was used to extract dates for the timelines, locations for maps, as well as epithets - various characteristics that Tolstoy so loved to reward his characters. Everyone remembers the mustache of the little princess, the wife of Bolkonsky, but many thought that the most brilliant handsome Andrei had “small plump handles” (and this in combination with a small height), and the elegant thin Natasha Rostova had a “fat neck” and the big mouth?

Anyone can download the application and make many more discoveries in the same spirit. In the meantime, we will return to our studies and continue to “anatomize” the texts with the help of Compreno, look for new, unexpected things in them and reveal the mysterious “code of Tolstoy”, which made his works immortal.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/273301/

All Articles