Images and Docker containers in pictures

Translation of the post Visualizing Docker Containers and Images , from beginner to beginner, the author with simple examples explains the basic entities and processes in the use of docker.

If you do not know what Docker is or do not understand how it relates to virtual machines or configuration management tools, then this post may seem a bit complicated.

')

The post is intended for those who are trying to master docker cli, to understand the difference between the container and the image. In particular, the difference between just the container and the running container will be explained.

In the process of development, you need to imagine some of the underlying details, for example, the layers of the UnionFS file system. Over the last couple of weeks I have been learning technology, I am new to the docker world, and the docker command line seemed rather difficult to master.

In my opinion, understanding how technology works from the inside is the best way to quickly master a new tool and use it correctly. Often a new technology develops new models of abstractions and introduces new terms and metaphors that may seem to be understandable at the beginning, but without a clear understanding make it difficult to use the tool later.

A good example is git. I could not understand Git until I understood its base model, including trees, blobs, commits, tags, tree-ish, and so on. I think that people who do not understand the guts of Git cannot masterfully use this tool.

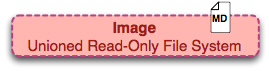

Image Definition (Image)

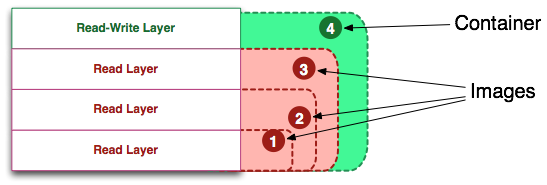

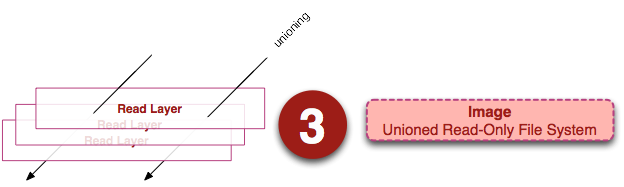

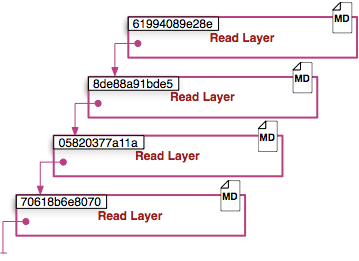

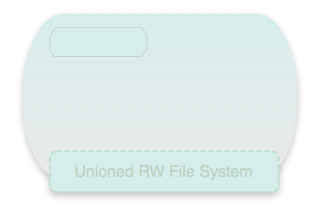

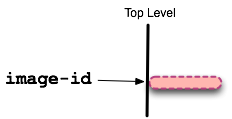

The visualization of the image is presented below in two forms. An image can be defined as an “entity” or a “general view” (union view) of a stack of read-only layers.

On the left we see a stack of layers for reading. They are shown only for understanding the internal device; they are accessible outside the running container on the host system. It is important that they are read-only (immutable), and all changes occur in the top layer of the stack. Each layer can have one parent, the parent also has a parent, etc. The top-level layer can be used as UnionFS (AUFS in my case with docker) and presented as a single read-only file system in which all layers are reflected. We see this “essence” of the image in the figure on the right.

If you want to look at these layers in their original form, you can find them in the file system on the host machine. They are not visible directly from the running container. On my host machine, I can find images in / var / lib / docker / aufs.

# sudo tree -L 1 /var/lib/docker/ /var/lib/docker/ ├── aufs ├── containers ├── graph ├── init ├── linkgraph.db ├── repositories-aufs ├── tmp ├── trust └── volumes 7 directories, 2 files Container Definition

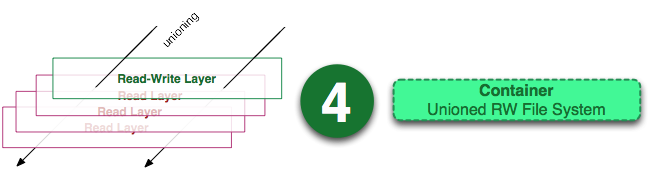

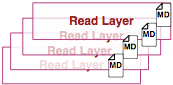

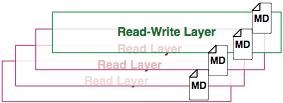

The container can be called the “entity” of a stack of layers with a top layer for writing.

The image above shows roughly the same thing as the image of the image, except that the top layer is available for recording. You may have noticed that this definition says nothing about whether the container is running or not, and this is no accident. The separation of containers into running and not running eliminated confusion in my understanding.

The container defines only a layer for writing at the top of the image (stack of layers for reading). He is not running.

Determining the running container

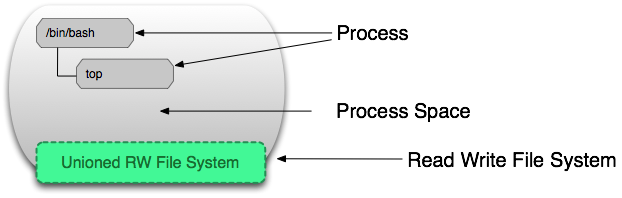

A running container is a “general view” of a read / write container and its isolated process space. Below is a container in its own process space.

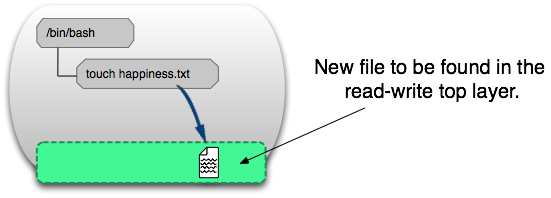

File system isolation provided by kernel-level technologies, cgroups, namespaces, and others, allows the docker to be such a promising technology. Processes in container space can change, delete, or create files that are stored in the top layer for writing. See the image:

To check this, run the command on the host machine:

docker run ubuntu touch happiness.txt You can find a new file in the write layer on the host machine, even if the container is not running.

# find / -name happiness.txt /var/lib/docker/aufs/diff/860a7b...889/happiness.txt Image layer definition

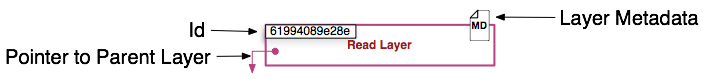

Finally, we define the image layer. The image below represents the image layer and lets us know that the layer is not just a change in the file system.

Metadata — Additional layer information that allows the docker to save information at run time and at build time. Both kinds of layers (for reading and writing) contain metadata.

In addition, as we mentioned earlier, each layer contains a pointer to the parent, using id (in the image, the parent layers are below). If the layer does not point to the parent layer, then it is at the top of the stack.

Metadata Location

At the moment (I understand that the docker developers can later change the implementation), the metadata of the image layers (for reading) are in a file called “json” in the / var / lib / docker / graph / id_ layer:

/var/lib/docker/graph/e809f156dc985.../json where "e809f156dc985 ..." is a stripped down layer id.

Tie it all together

Now, let's look at the commands, illustrated with clear pictures.

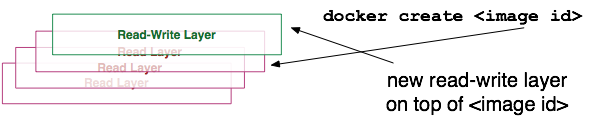

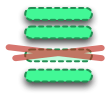

docker create <image-id>

Before:

After:

The 'docker create' command adds a layer to write to the top of the stack of layers found by <image-id>. The command does not start the container.

docker start <container-id>

Before:

After:

The 'docker start' command creates process space around the container layers. There can be only one process space per container.

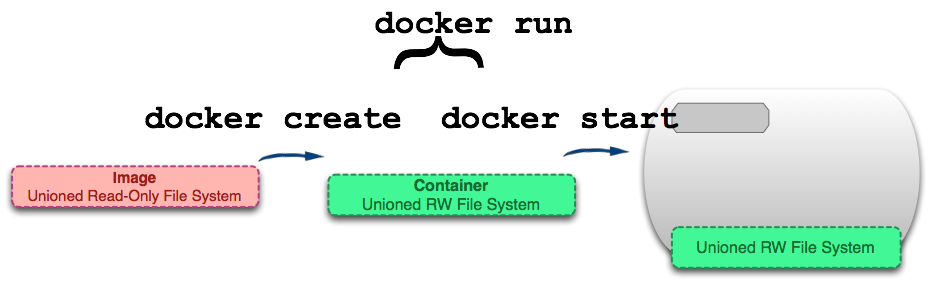

docker run <image-id>

Before:

After:

One of the first questions people ask (I also asked): “What is the difference between 'docker start' and 'docker run'?” One of the initial goals of this post is to explain this subtlety.

As we can see, the 'docker run' command finds the image, creates a container on top of it and starts the container. This is done for convenience and hides the details of the two teams.

Continuing the comparison with mastering Git, I will say that the 'docker run' is very similar to 'git pull'. Just like 'git pull' (which combines 'git fetch' and 'git merge'), the 'docker run' command combines two commands that can be used independently. This is convenient, but at first it can be misleading.

docker ps

The command 'docker ps' lists the running containers on your host machine. It is important to understand that this list includes only running containers, not running containers are hidden. To view a list of all containers, use the following command.

docker ps -a

The command 'docker ps -a', where 'a' - short for 'all' lists all containers, regardless of their state.

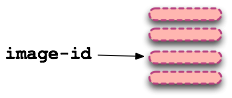

docker images

The 'docker images' command displays a list of top-level images. In fact, nothing special distinguishes the image from the layer to read. Only those images that have attached containers or those that were obtained using pull are considered top-level images. This distinction is necessary for convenience, since behind each image of the upper level there can be multiple layers.

docker images -a

The command 'docker images -a' prints all the images on the host machine. This is actually a list of all layers for reading in the system. If you want to see all the layers of a single image, use the 'docker history' command.

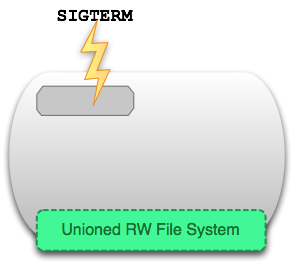

docker stop <container-id>

Before:

After:

The 'docker stop' command sends a SIGTERM signal to the running container, which gently stops all processes in the container's process space. As a result, we get a non-running container.

docker kill <container-id>

Before:

After:

The 'docker kill' command sends a SIGKILL signal, which immediately terminates all processes in the current container. This is almost the same as pressing Ctrl + \ in the terminal.

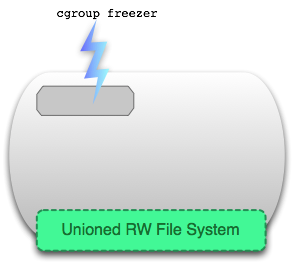

docker pause <container-id>

Before:

After:

Unlike 'docker stop' and 'docker kill', which send real UNIX signals to container processes, the 'docker pause' command uses a special cgroups feature to freeze running process space. Details can be read here , if in brief, sending the Ctrl + Z signal (SIGTSTP) is not enough to freeze all processes in the container space.

docker rm <container-id>

Before:

After:

The 'docker rm' command removes the write layer that defines the container on the host system. Must be run on stopped containers. Removes files.

docker rmi <image-id>

Before:

After:

The 'docker rmi' command removes the layer for reading, which defines the “essence” of the image. It deletes the image from the host system, but the image can still be obtained from the repository via 'docker pull'. You can use 'docker rmi' only for top-level layers (or images), you need to use 'docker rmi -f' to remove intermediate layers.

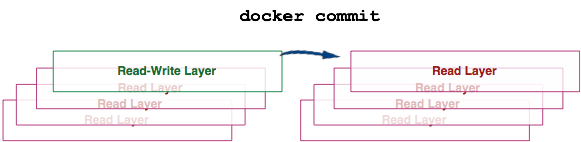

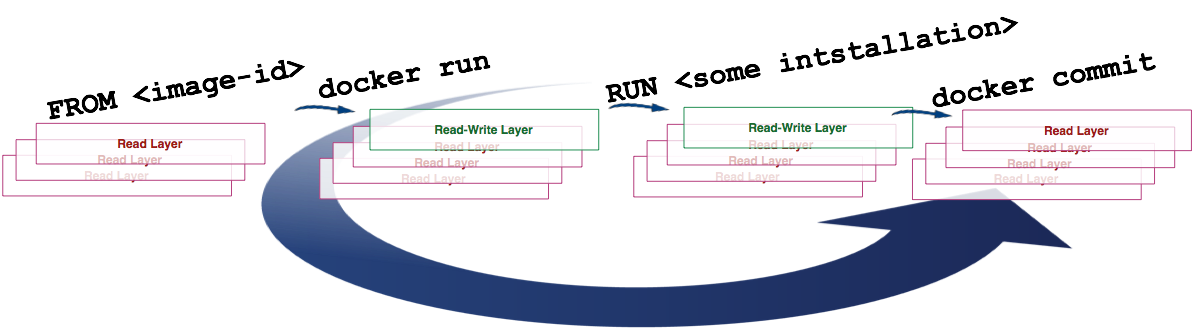

docker commit <container-id>

Before:

or

or

After:

The 'docker commit' command takes the top level of the container, which is for writing and turns it into a layer for reading. This actually turns the container (regardless of whether it is running) into an immutable image.

docker build

Before:

Dockerfile

and

and

After:

With many other layers.

The 'docker build' command is interesting because it launches a number of commands:

In the image above, we see how the build command uses the value of the FROM instruction from the Dockerfile file as the base image, after which:

1) starts the container (create and start)

2) changes the layer to write

3) commit

At each iteration, a new layer is created. When doing docker build, multiple layers can be created.

docker exec <running-container-id>

Before:

After:

The 'docker exec' command applies to the running container, starts a new process inside the container's process space.

docker inspect <container-id> | <image-id>

Before:

or

or

After:

The 'docker inspect' command gets the metadata of the top layer of the container or image.

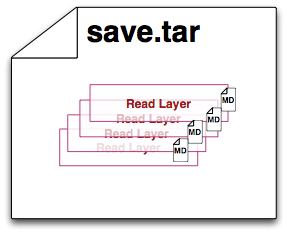

docker save <image-id>

Before:

After:

The 'docker save' command creates one file that can be used to import an image to another host system. Unlike the 'export' command, it saves all the layers and their metadata. Can only be applied to images.

docker export <container-id>

Before:

After:

The 'docker export' command creates a tar archive with the contents of the container files, resulting in a folder suitable for use outside of docker. The team removes the layers and their metadata. Can only be applied to containers.

docker history <image-id>

Before:

After:

The 'docker history' command accepts <image-id> and recursively lists all layers of the image's parents (which can also be images)

Total

I hope you enjoyed this visualization of containers and images. There are many other commands (pull, search, restart, attach, and others) that may or may not be explained by my comparisons.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/272145/

All Articles