Using handle and intrusive reference counter-s in multi-threaded environments in the C language

Access to the same data in several streams is considered bad practice, but in many cases it is inevitable, and this is not the issue discussed here. The question that is being discussed here is how to organize such access in the most secure way. Also, atomic operations are not discussed here, which are mentioned here: different compilers offer various means for such operations.

In a multithreaded environment when using an object or data structure, one of the main issues, among other things, is a guarantee that the object to which access is being made is still alive and the memory allocated for the structure is not freed.

This can be done in several ways, but we will only speak about two of them: handles and intrusive reference counters.

Handles are small structures that contain a pointer to a data object and ancillary data to ensure that the object is still alive. As a rule, two functions are written to work with handles: lock_handle and unlock_handle (the names are chosen arbitrarily to show functionality). Lock_handle checks the “vividness” of the object, increases the atomic reference counter and returns a pointer to the data object, if it is still available. If not, the function returns NULL, or by using another method, lets know that the object is no longer available. According to its name, unlock_handle atomically decreases the reference count and, as soon as it reaches the value 0, deletes the object.

')

Embedded reference counters are atomic numeric variables within the data object that count the number of references in the program to the specified data object. As soon as the reference count reaches 0, the object is deleted.

Now let's take a look at the advantages and common mistakes of both strategies and determine which one is better to use in specific cases. First, let's deal with the built-in reference counters.

Built-in reference counters, as the name implies, must be embedded in the data structure: this is an atomic integer. In a simple structure, let's call it data_packet_s, a similar modification might look like this:

=>

This is the main disadvantage of this approach: it needs modification of the data structure, so it can be used only for such structures that we can change. We cannot use it with an arbitrary data type or structures, for example, library ones.

Curiously, this is also an advantage. The advantage is that we do not need any additional structures and additional memory allocation for such structures.

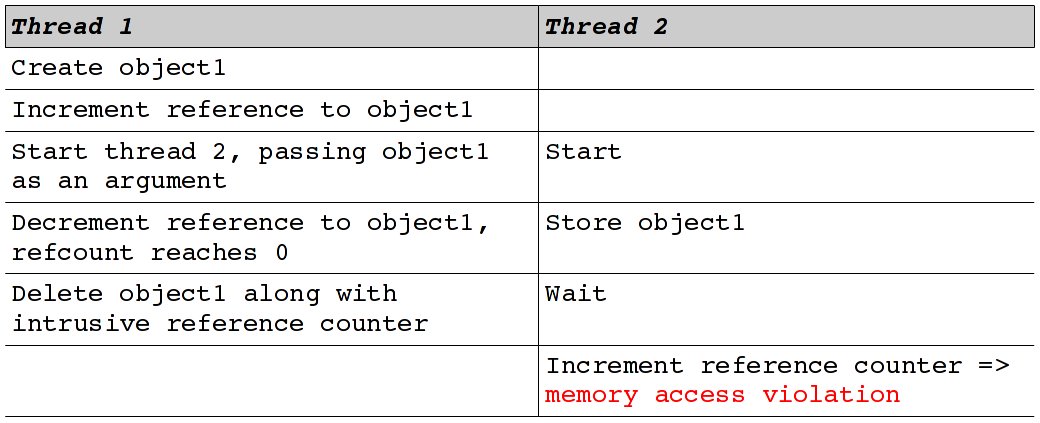

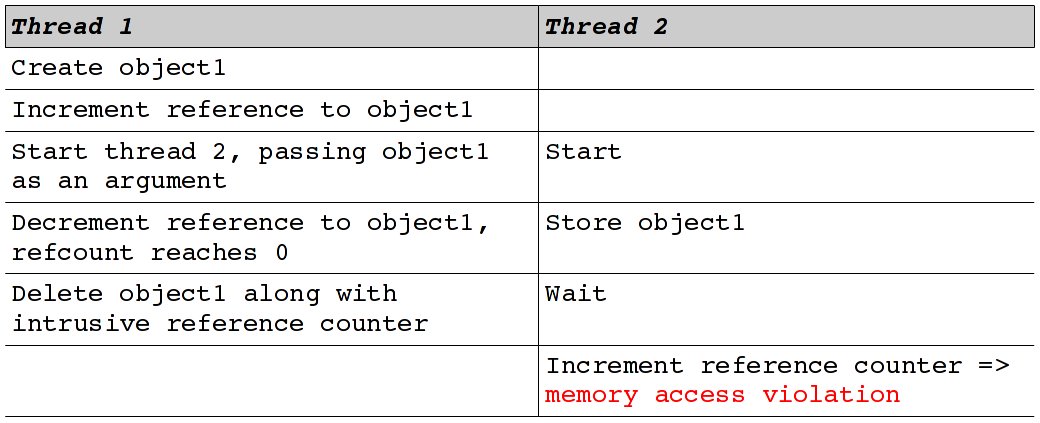

Another drawback, or rather, the specifics of this approach, is the following: the accessibility of the object must be guaranteed when the reference counter is incremented. In other words, we cannot simply store a pointer to an object and wait for the moment when we want to access it, and then simply increase the reference count and continue working with the object, because between the moment when we save the pointer and the moment when we start using the object, can be destroyed, and the reference count is also destroyed. Let's demonstrate the simple case of such an event using a simple conditional language.

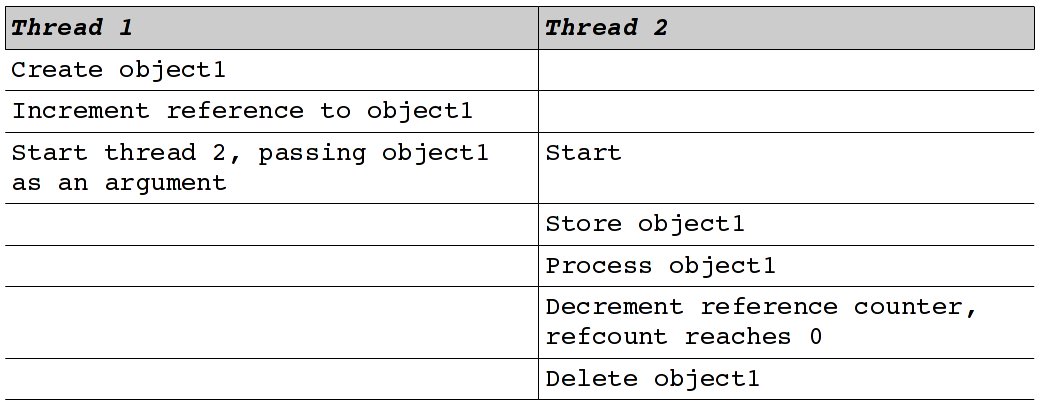

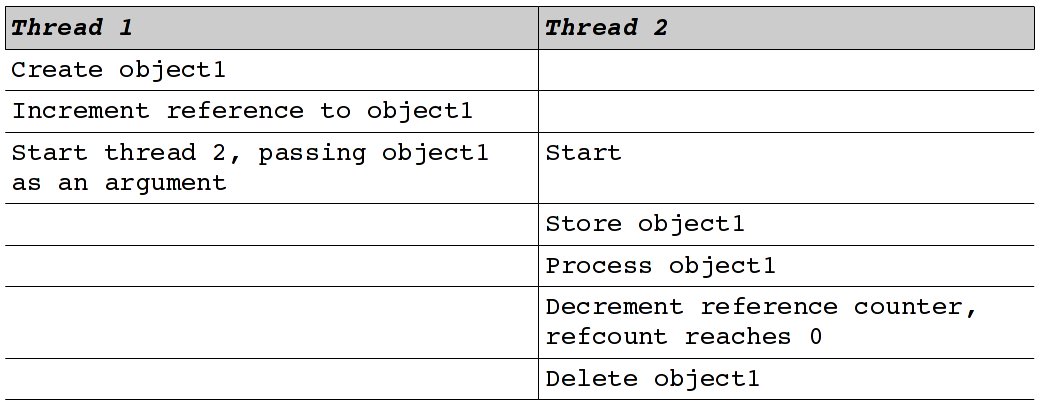

In this case, in order to ensure the integrity of the object, you will have to increase the number of links in stream 1 and transfer the resulting link to the ownership of stream 2 (stream 2 will decrease reference_count after the object is no longer needed). In other words, this scheme can work very well if it is necessary to process an object in another thread and forget about it. This can be demonstrated by the following illustration:

Such a scheme can be used by any number of threads, provided that each stream that increases the reference count already owns at least one link instance (either increased the number of links and did not transfer ownership, or received a copy reference into ownership from another thread) . Thus, in the latter case, stream 1 can increase the reference count several times (one for each stream) and only after that it can start several threads (as much as the reference count has been increased.

Here the second drawback is also visible: we increase and decrease the reference count in different threads, which can often lead to various errors, ranging from memory leaks when the link is not released, ending with the double release of the link and, accordingly, false release of the object, which leads to its removal the time it is still used in another thread or threads.

This scheme implements the so-called “shared ownership”, when the threads jointly own the object, and the thread that reduces the reference count to zero will delete the object.

And if you want to save a pointer to an object in one of the streams, and using it if necessary, you will see that the memory allocated by your program will grow with each stored object, because the stream will never release a reference to the object whose “vividness” it wants to guarantee .

Another possible error in such an approach is to refer to indirectly transmitted objects, that is, objects that are passed by a pointer contained in one of the other, directly or indirectly transmitted objects that refer but do not own the object. All such objects should be known, and safe access to all such objects should be provided if they are used along with the main one.

So let's summarize the advantages and disadvantages of the built-in reference counters:

Disadvantages:

Benefits:

Handles are lightweight structures that are passed by value, they reference the object, manage the links, and ensure the integrity of the object.

Obviously, handles that refer to the same object will have a pointer to one reference count. As a rule, this means that the reference count must be allocated on the heap dynamically. The simplest handle structure that comes to mind first may look like this:

Where reference_count is highlighted when creating the first handle to this object.

The first drawback of this approach is already obvious. We have to manage another additional structure, allocate another area of memory for the reference counter. But it pays off if you want to use reference counting with structures you don’t have access to.

A typical application of such a handle will be as follows:

Let's see what happens when the last object reference is deleted. First of all, we obviously want the managed object to be deleted. If the object is a simple piece of allocated memory, we just want the memory used by the object to be freed. But in most cases it is not. As in the above example, data_packet_s, where we would like to free also the data_buffer memory. If we use the handle for only one type of object, this does not create a big problem. But if we want the handle to handle different types, this introduces another question: how to remove the managed object correctly?

We can add another field to the handle: a pointer to the function that will be used to destroy / release the managed object. Now the handle looks like this:

Now the release_handle does not have to know the specifics of the object, in order to delete it, it will simply use the function that we saved in the handle, so let's go back to what happens when the last link is released.

After that we would like to free the memory that contains the reference_count. But it was not there: make it a terrible mistake. If other handles on the same object are still stored in other threads, after freeing the memory, they will refer to reference_count, which has already been deleted. And on the next attempt to access the object, we will have an attempt to access the freed memory.

Is there a solution that would prevent memory leaks but at the same time avoid calls to the freed memory of reference counters? There is such a way. This is a pool of objects that will be managed by freed counters. And this is where the problem arises, which can be quite difficult to find, and which is known as the “ABA problem”. Imagine a situation where you have a handle to an object. One of the threads deletes the object. Then another object is constructed, and a control handle is created for it. What happens?

When an object is destroyed, the reference_count associated with this object (let's call it object1) is released back to the object pool with a value of 0. So far, everything goes according to plan. But when another handle is allocated for a new object (let's call it object2), the reference_count that will be associated with this object is taken from the object pool, and this reference_count is set to 1. Now imagine that the stream storing the handle on object1 is trying to get a pointer. This will succeed because the reference_count pointed to by this handle is no longer 0, although it now belongs to object2. The lock function will return an incorrect pointer, the program (if lucky) will crash, or (if unlucky) damage the memory contents by referring to the freed section.

The solution, of course, exists, otherwise I would not have written all this.

We want to make the handle_s structure as easy as possible in order to be able to pass it by value, not by pointer, so let's do the following: create two structures, one of which will be a “weak” handle, that is, do not limit or check the object it manages, and the other will be a “strong” handle, i.e. one that will have a hard link with a particular managed object and will return NULL if the “weak” handle associated with it no longer refers to the same object.

Let's define them like this:

So, as you can see, now both handles have a “version” field, and strong_handle_s no longer has a pointer to an object, since it is now stored in general for the weak_handle_s object.

Let's see how he protects us from the ABA problem shown above.

In strong_handle_s and weak_handle_s that refer to the same object there are “version” fields that are equal to each other.

Whenever the handle is released and the weak_handle_s is placed back into the pool of objects, we will increment the version number in the weak_handle_s.

The next time, if a weak_handle_s released into the pool is reused to process another object, it will have a version number different from the version number of the object that was released. Now in the lock_handle function, comparing the version fields in both the “weak” and “strong” handles, we can tell whether the weak_handle_s still refers to the object whose pointer we are trying to get from strong_handle_s, and return NULL if it is not .

So, as we can see, handles bring some fairly complex problems, but it also has its advantages: the handle can be saved and forgotten until we need the object it controls; the handle is not inline, which means that we can use it with almost any type of data.

In addition, the transfer of a handle does not necessarily mean the transfer of ownership of the object, so that it can be used instead of a pointer as a safe link to objects wherever they are not the property of the referencing object (in data structures, etc.).

Thus handles are more difficult to manage. But their capabilities are much more powerful.

Disadvantages:

Benefits:

The built-in reference counter implements general strong references, which must hold the reference counter until the object is guaranteed to be unclaimed. Until all links are broken, the object will not be deleted. If the link is unlocked in a stream that has owned only one link, this thread will no longer be able to safely get another link guaranteed.

Handle implements a common weak reference. If the object is alive, the lock_handle function will return a pointer to the requested object, and the object is guaranteed not to be deleted until the handle is unlocked. It is safe to lock and unlock as many times as you want, since the handle is a separate object and is guaranteed to be a valid memory location. Appropriate measures must be taken to ensure that the shared memory of the reference counter is not released when the object reaches the reference counter 0, and that the reused reference counter is not used to check the number of references to already released objects.

In a multithreaded environment when using an object or data structure, one of the main issues, among other things, is a guarantee that the object to which access is being made is still alive and the memory allocated for the structure is not freed.

This can be done in several ways, but we will only speak about two of them: handles and intrusive reference counters.

Handles are small structures that contain a pointer to a data object and ancillary data to ensure that the object is still alive. As a rule, two functions are written to work with handles: lock_handle and unlock_handle (the names are chosen arbitrarily to show functionality). Lock_handle checks the “vividness” of the object, increases the atomic reference counter and returns a pointer to the data object, if it is still available. If not, the function returns NULL, or by using another method, lets know that the object is no longer available. According to its name, unlock_handle atomically decreases the reference count and, as soon as it reaches the value 0, deletes the object.

')

Embedded reference counters are atomic numeric variables within the data object that count the number of references in the program to the specified data object. As soon as the reference count reaches 0, the object is deleted.

Now let's take a look at the advantages and common mistakes of both strategies and determine which one is better to use in specific cases. First, let's deal with the built-in reference counters.

Built-in reference counters

Built-in reference counters, as the name implies, must be embedded in the data structure: this is an atomic integer. In a simple structure, let's call it data_packet_s, a similar modification might look like this:

struct data_packet_s { void *data_buffer; size_t data_buffer_size; }; =>

struct data_packet_s { void *data_buffer; size_t data_buffer_size; volatile int reference_count; }; This is the main disadvantage of this approach: it needs modification of the data structure, so it can be used only for such structures that we can change. We cannot use it with an arbitrary data type or structures, for example, library ones.

Curiously, this is also an advantage. The advantage is that we do not need any additional structures and additional memory allocation for such structures.

Another drawback, or rather, the specifics of this approach, is the following: the accessibility of the object must be guaranteed when the reference counter is incremented. In other words, we cannot simply store a pointer to an object and wait for the moment when we want to access it, and then simply increase the reference count and continue working with the object, because between the moment when we save the pointer and the moment when we start using the object, can be destroyed, and the reference count is also destroyed. Let's demonstrate the simple case of such an event using a simple conditional language.

In this case, in order to ensure the integrity of the object, you will have to increase the number of links in stream 1 and transfer the resulting link to the ownership of stream 2 (stream 2 will decrease reference_count after the object is no longer needed). In other words, this scheme can work very well if it is necessary to process an object in another thread and forget about it. This can be demonstrated by the following illustration:

Such a scheme can be used by any number of threads, provided that each stream that increases the reference count already owns at least one link instance (either increased the number of links and did not transfer ownership, or received a copy reference into ownership from another thread) . Thus, in the latter case, stream 1 can increase the reference count several times (one for each stream) and only after that it can start several threads (as much as the reference count has been increased.

Here the second drawback is also visible: we increase and decrease the reference count in different threads, which can often lead to various errors, ranging from memory leaks when the link is not released, ending with the double release of the link and, accordingly, false release of the object, which leads to its removal the time it is still used in another thread or threads.

This scheme implements the so-called “shared ownership”, when the threads jointly own the object, and the thread that reduces the reference count to zero will delete the object.

And if you want to save a pointer to an object in one of the streams, and using it if necessary, you will see that the memory allocated by your program will grow with each stored object, because the stream will never release a reference to the object whose “vividness” it wants to guarantee .

Another possible error in such an approach is to refer to indirectly transmitted objects, that is, objects that are passed by a pointer contained in one of the other, directly or indirectly transmitted objects that refer but do not own the object. All such objects should be known, and safe access to all such objects should be provided if they are used along with the main one.

So let's summarize the advantages and disadvantages of the built-in reference counters:

Disadvantages:

- Built-in counters require data structure changes

- The link must remain locked until there is a chance that the object will be used.

- Link ownership is passed between threads.

- Careful attention should be given to indirectly transferred objects.

Benefits:

- No additional structures and memory operations are required.

Handles

Handles are lightweight structures that are passed by value, they reference the object, manage the links, and ensure the integrity of the object.

Obviously, handles that refer to the same object will have a pointer to one reference count. As a rule, this means that the reference count must be allocated on the heap dynamically. The simplest handle structure that comes to mind first may look like this:

struct handle_s { volatile int *reference_count; void *object; }; Where reference_count is highlighted when creating the first handle to this object.

The first drawback of this approach is already obvious. We have to manage another additional structure, allocate another area of memory for the reference counter. But it pays off if you want to use reference counting with structures you don’t have access to.

A typical application of such a handle will be as follows:

struct some_struct_s *object = lock_handle(hdata); if(object) { use(object); release_handle(hdata); }; Let's see what happens when the last object reference is deleted. First of all, we obviously want the managed object to be deleted. If the object is a simple piece of allocated memory, we just want the memory used by the object to be freed. But in most cases it is not. As in the above example, data_packet_s, where we would like to free also the data_buffer memory. If we use the handle for only one type of object, this does not create a big problem. But if we want the handle to handle different types, this introduces another question: how to remove the managed object correctly?

We can add another field to the handle: a pointer to the function that will be used to destroy / release the managed object. Now the handle looks like this:

struct handle_s { volatile int *reference_count; void *object; void (*destroy_object)(void*); }; Now the release_handle does not have to know the specifics of the object, in order to delete it, it will simply use the function that we saved in the handle, so let's go back to what happens when the last link is released.

After that we would like to free the memory that contains the reference_count. But it was not there: make it a terrible mistake. If other handles on the same object are still stored in other threads, after freeing the memory, they will refer to reference_count, which has already been deleted. And on the next attempt to access the object, we will have an attempt to access the freed memory.

Is there a solution that would prevent memory leaks but at the same time avoid calls to the freed memory of reference counters? There is such a way. This is a pool of objects that will be managed by freed counters. And this is where the problem arises, which can be quite difficult to find, and which is known as the “ABA problem”. Imagine a situation where you have a handle to an object. One of the threads deletes the object. Then another object is constructed, and a control handle is created for it. What happens?

When an object is destroyed, the reference_count associated with this object (let's call it object1) is released back to the object pool with a value of 0. So far, everything goes according to plan. But when another handle is allocated for a new object (let's call it object2), the reference_count that will be associated with this object is taken from the object pool, and this reference_count is set to 1. Now imagine that the stream storing the handle on object1 is trying to get a pointer. This will succeed because the reference_count pointed to by this handle is no longer 0, although it now belongs to object2. The lock function will return an incorrect pointer, the program (if lucky) will crash, or (if unlucky) damage the memory contents by referring to the freed section.

The solution, of course, exists, otherwise I would not have written all this.

We want to make the handle_s structure as easy as possible in order to be able to pass it by value, not by pointer, so let's do the following: create two structures, one of which will be a “weak” handle, that is, do not limit or check the object it manages, and the other will be a “strong” handle, i.e. one that will have a hard link with a particular managed object and will return NULL if the “weak” handle associated with it no longer refers to the same object.

Let's define them like this:

struct weak_handle_s { volatile int version; volatile int reference_count; void object; void (*destroy_object)(void*); }; struct strong_handle_s { struct weak_handle_s *handle; int version; }; So, as you can see, now both handles have a “version” field, and strong_handle_s no longer has a pointer to an object, since it is now stored in general for the weak_handle_s object.

Let's see how he protects us from the ABA problem shown above.

In strong_handle_s and weak_handle_s that refer to the same object there are “version” fields that are equal to each other.

Whenever the handle is released and the weak_handle_s is placed back into the pool of objects, we will increment the version number in the weak_handle_s.

The next time, if a weak_handle_s released into the pool is reused to process another object, it will have a version number different from the version number of the object that was released. Now in the lock_handle function, comparing the version fields in both the “weak” and “strong” handles, we can tell whether the weak_handle_s still refers to the object whose pointer we are trying to get from strong_handle_s, and return NULL if it is not .

So, as we can see, handles bring some fairly complex problems, but it also has its advantages: the handle can be saved and forgotten until we need the object it controls; the handle is not inline, which means that we can use it with almost any type of data.

In addition, the transfer of a handle does not necessarily mean the transfer of ownership of the object, so that it can be used instead of a pointer as a safe link to objects wherever they are not the property of the referencing object (in data structures, etc.).

Thus handles are more difficult to manage. But their capabilities are much more powerful.

Disadvantages:

- Needs additional structure and memory.

- Takes extra processor time

- Adds some non-obvious problems.

Benefits:

- Allows you to save handles and have access to them as needed.

- Does not require that the object is permanently owned.

findings

The built-in reference counter implements general strong references, which must hold the reference counter until the object is guaranteed to be unclaimed. Until all links are broken, the object will not be deleted. If the link is unlocked in a stream that has owned only one link, this thread will no longer be able to safely get another link guaranteed.

Handle implements a common weak reference. If the object is alive, the lock_handle function will return a pointer to the requested object, and the object is guaranteed not to be deleted until the handle is unlocked. It is safe to lock and unlock as many times as you want, since the handle is a separate object and is guaranteed to be a valid memory location. Appropriate measures must be taken to ensure that the shared memory of the reference counter is not released when the object reaches the reference counter 0, and that the reused reference counter is not used to check the number of references to already released objects.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/266901/

All Articles