Why SMS is limited to 160 characters, and Twitter messages - 140 characters?

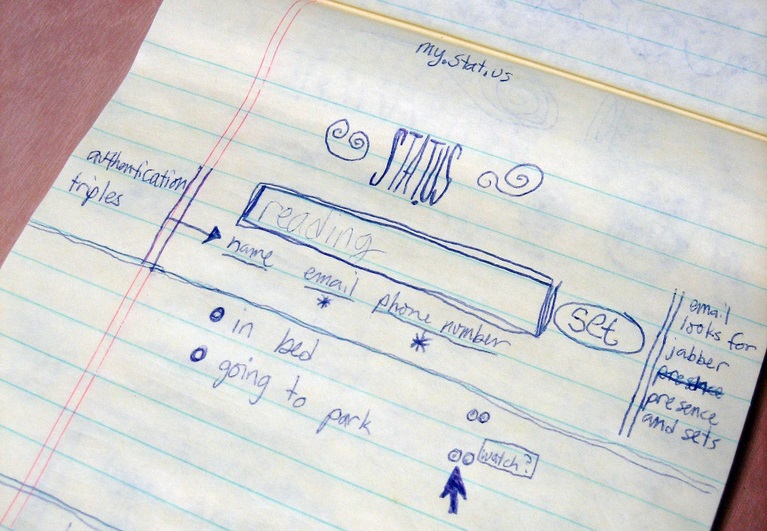

A document from the Twitter archive, circa 2000, the working title of Twitter is “Stat.us”. Credit: Jack Dorsey

It was 1985 year. Friedhelm Hillebrand worked hard at a table in the empty room of his house in Bonn (Germany), and continuously typed random phrases: news, requests, questions ... all mixed up. Having finished printing the next page, Hillebrand counted the number of letters, numbers, punctuation marks and spaces in each sentence printed on the page, and was immediately taken to the next page.

It was 1985 year. Friedhelm Hillebrand worked hard at a table in the empty room of his house in Bonn (Germany), and continuously typed random phrases: news, requests, questions ... all mixed up. Having finished printing the next page, Hillebrand counted the number of letters, numbers, punctuation marks and spaces in each sentence printed on the page, and was immediately taken to the next page.At that time, communications companies were faced with the acute problem of developing a technological standard that would allow mobile phones to transmit and display text messages on the screen.

Since at that time the capabilities of wireless networks were rather limited, and the majority of consumers accounted for car phones, and not at all wearable electronics, it was necessary to offer a reasonable, but strict restriction for the maximum message length as part of the standard being developed.

')

"A hundred and fifty characters" ... Before experimenting with a typewriter, Hillebrand had a dispute with friends about the sufficiency of such a restriction for most mobile phone users.

“My friends assured me in one voice that such a restriction was too small for the mass market,” Hillebrand recalls, and adds: “but I was more optimistic.”

And his optimism was really important for the future of mobile technology. In those days, SMS was just about to become the predominant form of mobile communications. The first SMS with the text “Merry Christmas” will be sent by a twenty-two-year-old QA engineer Neil Papworth only on December 3, 1992. It is now text communications are used everywhere, and in 1985 everything was just beginning.

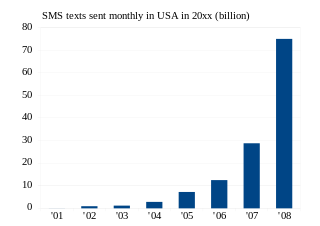

According to a study by Nielsen Mobile (for the US market), a significant event occurred in the fourth quarter of 2007 — then, for the first time in history, SMS bypassed voice calls in terms of frequency of use (in that quarter, the average mobile user in the USA sent 218 SMS and made 213 calls per month) In the future, this gap only increased.

According to a study by Nielsen Mobile (for the US market), a significant event occurred in the fourth quarter of 2007 — then, for the first time in history, SMS bypassed voice calls in terms of frequency of use (in that quarter, the average mobile user in the USA sent 218 SMS and made 213 calls per month) In the future, this gap only increased.SMS services have become an economic boon for telecom operators. Giants such as Verizon Wireless and AT & T initially took 20-25 cents per message or $ 20 for unlimited SMS. Over time, prices decreased, but the number of subscribers and the messages they sent grew exponentially.

But back in 1985 to Hillebrand typing with a typewriter phrase. When he decided that there was enough data, and calculated the statistics of the lengths of all the phrases printed by him, it turned out that in a typical case, each individual informational message took one or two lines and consisted of no more than 160 characters. That's how it appeared - this is Hillebrand's magic number , which has become the standard for one of the most popular methods of digital communication at the present time - the technology of short text messages (SMS).

“I decided that 160 characters would be enough,” he now recalls his reflections in 1985, when he was 45. “Quite enough.”

Later, years later, in order to avoid the need to divide messages into parts when sending them from a mobile phone, the creators of Twitter chose the “tweet” length of exactly 160 characters, of which 140 characters were available to the user to write the message, and 20 characters were reserved for preserving the unique user addresses.

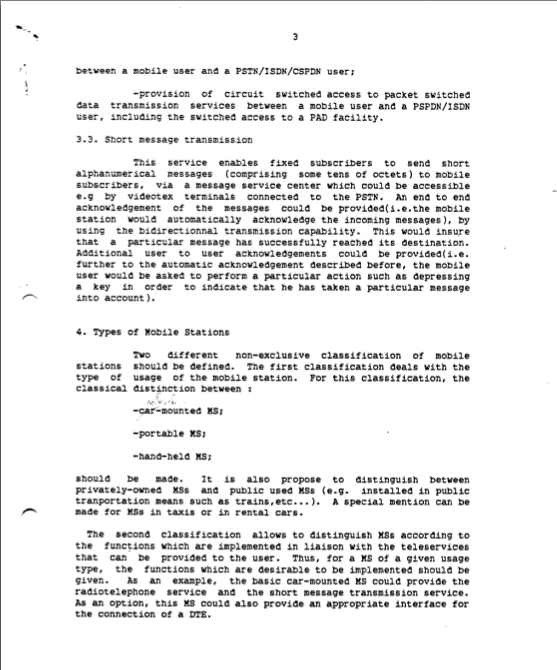

Later, years later, in order to avoid the need to divide messages into parts when sending them from a mobile phone, the creators of Twitter chose the “tweet” length of exactly 160 characters, of which 140 characters were available to the user to write the message, and 20 characters were reserved for preserving the unique user addresses.And in 1985, after completing his, let's say frankly, not too scientific research, Hillebrand moved on. As chairman of the non-voice services committee in the GSM analytic group, which, in fact, developed the standard of the same name, he “pushed through” a new group work plan on the standard in 1986, resulting in a new item in the standard that binds all mobile communication devices to support the service short text messages (SMS).

Hillebrand needed to find a suitable data transfer channel for micro-text messages, and one that would not require a major change to the existing GSM standard. In mobile networks there was a narrow auxiliary radio channel, which was used only for exchanging small informational messages: for example, about the strength of the tower signal or with meta information about an incoming call. The voice communication itself went along a separate, main channel.

“We were looking for a way to make it cheap,” Hillebrand recalls. “Most of the time nothing happened on this auxiliary line. So, in essence, it was an unused resource of the communication system. ”

Initially, the Hillebrand team intended to transmit messages with information blocks of 1024 bits in size. This required limiting messages to 128 characters, but this was not enough for many cases. Therefore, a compromise was made: to expand the information block to 1120 bits and at the same time reduce the allowable alphabet of messages, leaving only Latin letters and numbers in it (that is, using a seven-bit encoding). As a result, 160 characters began to fit into one information block.

Still, doubts remained about the sufficiency of the chosen limit. The committee did not have exactly any marketing research data, and they decided to rely on two “convincing arguments”:

- The first argument: it was argued that postcards most often contain messages less than 150 characters long - simply due to geometric constraints.

- The second argument: they analyzed a set of messages sent via Telex (telegraph network for business). Despite the absence of any technical limitations, Telex messages also never exceeded 150 characters.

Yes, and if you now look at the typical e-mail sent in our days, you will notice that the length of the subject line usually does not exceed the same 150 characters.

However, the limitation on the length of SMS was not the only problem of text messages as a way of communicating to mobile users. In those days, the process of typing text on a mobile phone was quite time consuming. The keys were physical and were intended to dial the numbers, so it was necessary to attach an additional 3-4 letters to each number key, which needed to be cycled through repeatedly pressing the same button. So a set of long sentences was a very painful task.

However, the limitation on the length of SMS was not the only problem of text messages as a way of communicating to mobile users. In those days, the process of typing text on a mobile phone was quite time consuming. The keys were physical and were intended to dial the numbers, so it was necessary to attach an additional 3-4 letters to each number key, which needed to be cycled through repeatedly pressing the same button. So a set of long sentences was a very painful task.But, despite all these difficulties, the text messaging service began to spread. And, remarkablely, the distribution went very quickly. Initially it was assumed that the SMS messaging service would occupy a small niche, evoking interest, say, among business users in the field of mobile office services. However, it turned out differently - Hillebrand could not imagine how quickly the SMS technology would truly receive universal recognition.

“No one could have imagined at what speed young people would master and begin to actively use SMS messages,” Hillebrand says. He is simply “fascinated” with stories about how young couples break off relationships through SMS.

Despite the booming technology of text messaging, Hillebrand did not become “rich” because there are no royalties to pay for sending text messages. He does not receive a penny when someone in the world sends another text message, while, say, the author of a song receives payments from the radio station for each broadcast of his song on the air.

Hillebrand now lives in Bonn and heads Hillebrand & Partners, a company that advises clients on technology patents. He is the author of a book about the history of the creation of GSM.

PS Links:

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/266733/

All Articles