Plot-oriented games

Classic computer games began, actually, before the advent of computers in the form of interactive books. Most likely, in your childhood you had one such or Braslavsky, or in general from the cycle about the Steel Rat of Harrison.

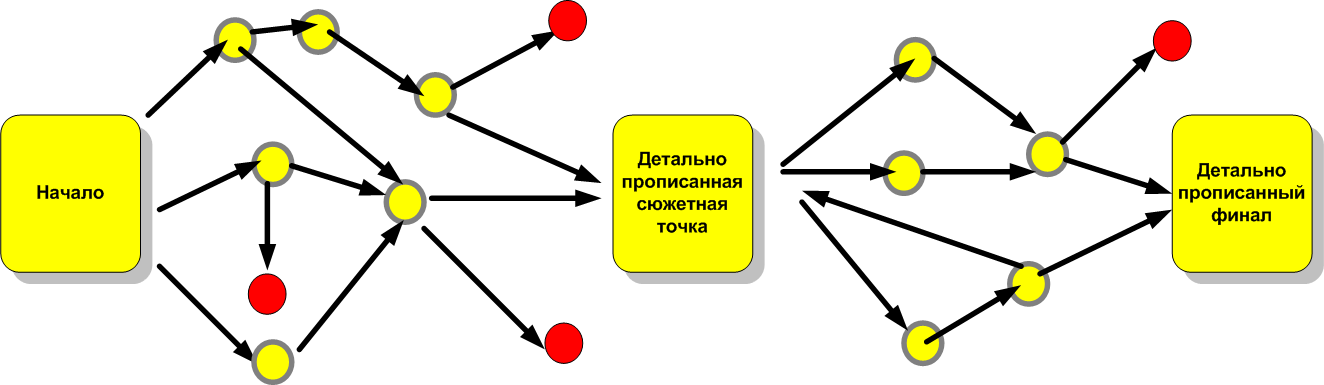

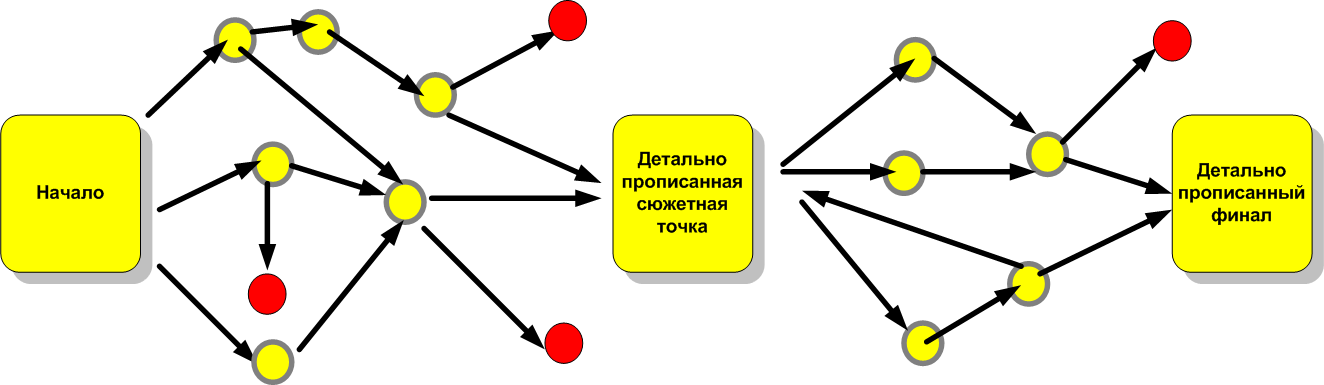

The meaning is very simple: there is a plot inside, which depends on your choice. The simplest branching is this: you have reached a fork. If you want to turn right, open page 11, if left - 182. On the appropriate pages will be a continuation of the story about what will happen after your choice.

')

The basic plot was built in the form of a system of nodes and transitions. In one pass, you used about 25-35% of the pages of the book.

That is, the technical variability was reduced to the fact that you still received 80% of the main plot, but simply not always linearly and not always from the same point of view. And there was almost no automation there, except that you looked through the pages.

For example, in “The Lord of the Boundless Desert” it was necessary to destroy several magicians: you basically determined the order of movement between them, and everything else was what in GameDev is called flavor - not related to mechanics, but very pleasant for the player .

At this stage, feedback books were few. There was an urgent need to improve the engine so that the player could feel a greater nonlinearity. Therefore, a certain basic role-playing system with a pair of indicators such as strength, hits or intelligence was placed on top of the plot. Opponents and checks of indicators appeared. The enemy is, in essence, a competition for throwing dice. He won - plus strength, go heal wounds. Immediately added the following:

That is, the book has acquired some more advanced level of automation - external generation of random numbers and external processing of checks were required “if your intellect is higher than 5, then go to page 73”.

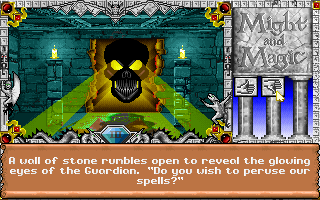

In this place from the book, in fact, turned out a text quest. Which was then repeatedly implemented immediately with the advent of computers. Here is an example without illustrations:

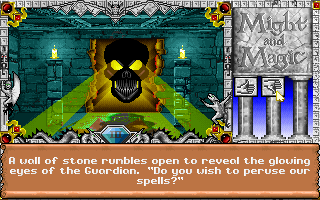

But with illustrations:

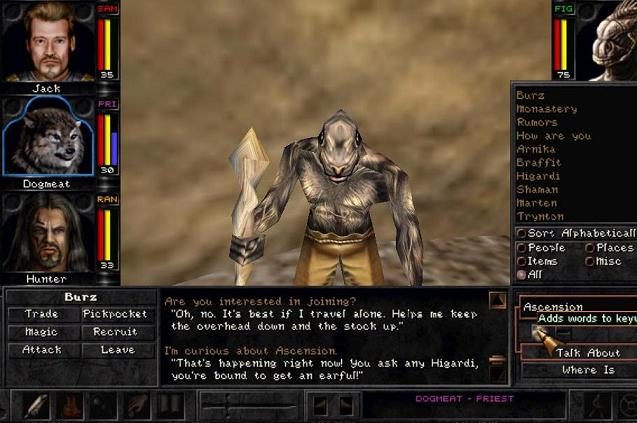

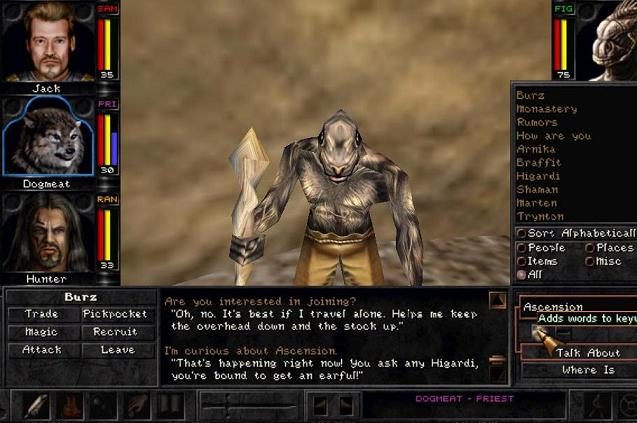

The last thing in this style that was directly rendered by the console is Wizardry VIII:

It was a classic text quest, but instead of illustrations - a normal 3D engine, the combat system is a normal step-by-step without a console mode such as “kick the nearest enemy with a foot”. And in the dialogues, you had to manually enter the words-topics to which the respondent spoke to you. For convenience, the most frequent were carried to the side panel.

As you can see, the level of automation in terms of the plot has grown slightly: we are still moving between the nodal points (most often - NPC with extensive dialogues) and sometimes do the work of bring-feed, getting into dangerous places.

On the other hand, with the development of computer technology, a fundamentally different branch of games appeared, consisting of pure mechanics. For example, Arkanoid . The setting will be slightly different, but still. But this example at one time dealt a powerful blow to the Russian economy, taking a hell of a lot of time in offices:

But one should not think that the game of mechanics (without the plot) is a pure manifestation of the possibility of giving feedback by automating the backend with the same processor. In board games, there has also always been a classic division into atmospheric games (usually an American school) and more abstract (early German) games.

Monopoly is a game of betting and throwing dice. However, if you remove the entire economic plot from it, it will become boring. On the other hand, the same chess was probably perceived in antiquity as a game for a realistic setting of the battle, but later became a pure abstract game of mechanics.

But back to progress. According to the logic of things, man-played games on mechanics had to be enumerated during the time of Atari, since a person thinks not so much to suck, but slowly enough. The last but one chess was surrendered, now Guo still holds on - there are many non-algorithms, both in complexity and in uncertainty of processes, and there is not enough processor resources for a full brute-force and its variety. That is, the capabilities of the hardware base with enough head, and to come up with something new after it would be difficult. In general, the main genres were born around then: in the book about DOOM, the creative process is described first by first inventing a scroller engine, then by a first-person-view 3D action game.

Nevertheless, although it seemed that it was necessary to dig in this direction, it was during the times of Atari and a little later (sometime before the 286s) huge story games appeared. Here, look, this is generally SEGA. A game with the scale and variety of the first Fallout, but packed in 2-4 megabytes:

Here is the modern remake:

Since then, only graphics have progressed significantly (in particular, 3D appeared, and the animation of the human skeleton was no longer done by artists like Prince of Persia, but thanks to the transfer of real movements of Motion Capture). However, the intensity of the plot and the methods of its presentation, we are not very far from the text quests with illustrations.

The plot can be another measure of progress and purpose of passage. For example, here in this senseless, merciless and (theoretically) infinite like Tetris game about Vikings. It all consists of repetitive fights.

So, there is a global story in the game, and you look through it interactively. The battle has passed - go to page 124.

At the same time, depending on the start, you have 4 main branches, which eventually lead to a global war and the fact that you unite all the tribes (in a positive ending), and then return home and continue endless fights, but without a special plot meaning . Nothing like?

Naturally, each subunit of the plot contains its own choice.

Here you can play the character and read new pieces of this interactive book. Yes, yes, this is an absolute repetition of the mechanics of the game book, only battles are more “computerized.”

So, the plot (and the setting) can be an end in itself. That is, to encourage players to play to the very, very end out of curiosity.

The plot can be a decoration. For example, humor in Galaxy on Fire is an optional thing, to play cool and so. But he is very happy throughout the story and decorates the game. It creates a special atmosphere of space hooliganism. Teaches us the features of our reckless character (and in role-playing games this unity is important to us). And, as a result, it offers strange strings for quests.

In more boring games, you often tolerate a monotonous piece for the sake of the plot. For example, in the last Fallout from the first person, something like this happened to me.

The plot can be learning. In the ingenious This War of Mine you have to constantly face the different horrors of war. Every day it gives you a choice - either to make your team worse or to do wrong. Take a look:

Like a blow to the head, right?

The game, of course, a little cunning. If the character was morally and physically in order (he kept good “karma”, that is, he did the necessary actions for the game to learn), then with him at the end of the plot everything will be in order. If not, it will be bad for him. The novel did a bad deed and will be punished:

And finally, the plot can be a mini-guide. That is, to put it in a gamedev-language, to shorten the action-result chain and give more concise sequences in response to the question “What should I do?”. In this regard, the plot, which is completely synergistic with the mechanics of the game, works well. Again, I will refer to board games as the closest example. In the Jackal you can put a pirate on the same cell, where there is another pirate. The latter in this case is transferred to your ship. We do not call this action "change the coordinates of the chips," but we say that you beat the enemy, and he went to the ship to lick his wounds. Or the goal of the game - to collect gold - directly follows from the fact that we are filibusters. Not noble environmentalists who came to this island to find crocodiles, but real pirates.

It is much easier to remember. In The Wizard of the Emerald City, children do not compare the position of their characters with the estimated function of time and play actions. They run away from Bastinda. It is clear that if an evil witch catches up with you - it is not very good. That gives rise to a children's scream of delight when Ellie steps forward. With an increase in the evaluation function, this would not have happened.

On the other hand, often for the sake of mechanics, you need to perform some kind of completely foolish actions - which destroys both the plot and the integrity of the game. For example, to collect some items at the levels when there is a war around. The main character is going to survive, and you make him climb for achivka every time - the plot immediately fray. For example, when in XCOM: Enemy Within they crammed up the “composition” collection (on ordinary missions, there were points where it was necessary to reach for a limited time), this, of course, remarkably changed the strategic depth. But it killed part of the plot, more precisely, made it somewhat absurd. That's because in the game world there was not enough convincing justification for these actions. Although, of course, a couple of sektoid interrogations and studies could clarify the situation if the game designer wanted.

Since the 80s, the number of holivars "plot against mechanics" has been growing in the game environment. A big open world against a closed one is essentially the same. If only because the infinite world cannot be completely written down by hands, that is, its plot will be automatic. Compare Daggerfall and Morrowind - there this difference is strongly noticeable. Or "Elite" and the same Galaxy on Fire. And so on.

A small example from our desktop market. The game consists of mechanics and setting. It is the combination of these two components that determines the interestingness of the game. For example, I can say for sure that any game about minions worth up to 1,500 rubles will be sold with a circulation of at least 5,000 pieces from September to the end of December. The mechanics are not important there - the children will disassemble these soulless yellow creatures that they clogged the brain with. On the other hand, the mechanics of the “Wizard of the Emerald City” alone would provide well for 1/10 of sales. There was an important plot (as a reference to the book) and art. At the same time, the game itself turned out to be not a storyline, but a purely igromechanical and with high replayability.

On the other hand, the same little dandy or word guessing games have a finite capacity - sooner or later all the stories will be answered, and the words will be remembered. Scenario modules for AD & D can be run once (okay, a maximum of 2-3 in the same batch if you embed them as places on the map and take into account that each time the batches go "tangentially" or die). That is, the plot is almost always one-time or lower replayability. How Bioware solves this problem, you probably know very well - you blame them on what the world is worth, but you buy supplements.

The difference between a plot-oriented game and a mechanical one , in essence, is only in the fact that the first one is an evolving book, and the second one is an evolved desktop. Mass Effect - an interactive film - the evolution of the book. Fallout is a very complex book evolution. Arkanoid - well, you must have seen pinball machines, this is a direct ancestor. Tetris, "Colored lines" - all this is understandable.

And what about Vangers, FTL, Sword and Glory and other games where the plot is fucking important, but, it seems, this is not a book? Very simple - there is a competent alternation of only purely igromekhanicheskikh things like fights or traveling around the world and plot. The slaughter effect and replayability largely depend on the degree of quality of the weave. By the way, yes, the plot provides a long, but a single batch - therefore, even 100% mechanical games have one-time goals. Especially noteworthy is the goal of "pass - show a cartoon".

The meaning is very simple: there is a plot inside, which depends on your choice. The simplest branching is this: you have reached a fork. If you want to turn right, open page 11, if left - 182. On the appropriate pages will be a continuation of the story about what will happen after your choice.

')

The basic plot was built in the form of a system of nodes and transitions. In one pass, you used about 25-35% of the pages of the book.

That is, the technical variability was reduced to the fact that you still received 80% of the main plot, but simply not always linearly and not always from the same point of view. And there was almost no automation there, except that you looked through the pages.

For example, in “The Lord of the Boundless Desert” it was necessary to destroy several magicians: you basically determined the order of movement between them, and everything else was what in GameDev is called flavor - not related to mechanics, but very pleasant for the player .

At this stage, feedback books were few. There was an urgent need to improve the engine so that the player could feel a greater nonlinearity. Therefore, a certain basic role-playing system with a pair of indicators such as strength, hits or intelligence was placed on top of the plot. Opponents and checks of indicators appeared. The enemy is, in essence, a competition for throwing dice. He won - plus strength, go heal wounds. Immediately added the following:

- Greater sense of progress - we defeat enemies, develop.

- Non-linearity according to the nature of development: a character with high intelligence must go one way, a strong one another.

- The need to climb in all the corners of the plot - there lay an expo or an increase in performance. Accordingly, having made a loop through 15 sections, we did not feel that it was superfluous.

- More variety (due to random numbers, as a rule) in the passage.

That is, the book has acquired some more advanced level of automation - external generation of random numbers and external processing of checks were required “if your intellect is higher than 5, then go to page 73”.

In this place from the book, in fact, turned out a text quest. Which was then repeatedly implemented immediately with the advent of computers. Here is an example without illustrations:

But with illustrations:

The last thing in this style that was directly rendered by the console is Wizardry VIII:

It was a classic text quest, but instead of illustrations - a normal 3D engine, the combat system is a normal step-by-step without a console mode such as “kick the nearest enemy with a foot”. And in the dialogues, you had to manually enter the words-topics to which the respondent spoke to you. For convenience, the most frequent were carried to the side panel.

As you can see, the level of automation in terms of the plot has grown slightly: we are still moving between the nodal points (most often - NPC with extensive dialogues) and sometimes do the work of bring-feed, getting into dangerous places.

On the other hand, with the development of computer technology, a fundamentally different branch of games appeared, consisting of pure mechanics. For example, Arkanoid . The setting will be slightly different, but still. But this example at one time dealt a powerful blow to the Russian economy, taking a hell of a lot of time in offices:

But one should not think that the game of mechanics (without the plot) is a pure manifestation of the possibility of giving feedback by automating the backend with the same processor. In board games, there has also always been a classic division into atmospheric games (usually an American school) and more abstract (early German) games.

Monopoly is a game of betting and throwing dice. However, if you remove the entire economic plot from it, it will become boring. On the other hand, the same chess was probably perceived in antiquity as a game for a realistic setting of the battle, but later became a pure abstract game of mechanics.

But back to progress. According to the logic of things, man-played games on mechanics had to be enumerated during the time of Atari, since a person thinks not so much to suck, but slowly enough. The last but one chess was surrendered, now Guo still holds on - there are many non-algorithms, both in complexity and in uncertainty of processes, and there is not enough processor resources for a full brute-force and its variety. That is, the capabilities of the hardware base with enough head, and to come up with something new after it would be difficult. In general, the main genres were born around then: in the book about DOOM, the creative process is described first by first inventing a scroller engine, then by a first-person-view 3D action game.

Nevertheless, although it seemed that it was necessary to dig in this direction, it was during the times of Atari and a little later (sometime before the 286s) huge story games appeared. Here, look, this is generally SEGA. A game with the scale and variety of the first Fallout, but packed in 2-4 megabytes:

Here is the modern remake:

Since then, only graphics have progressed significantly (in particular, 3D appeared, and the animation of the human skeleton was no longer done by artists like Prince of Persia, but thanks to the transfer of real movements of Motion Capture). However, the intensity of the plot and the methods of its presentation, we are not very far from the text quests with illustrations.

And, by the way, why in general the plot in games is igromechanically?

The plot can be another measure of progress and purpose of passage. For example, here in this senseless, merciless and (theoretically) infinite like Tetris game about Vikings. It all consists of repetitive fights.

So, there is a global story in the game, and you look through it interactively. The battle has passed - go to page 124.

At the same time, depending on the start, you have 4 main branches, which eventually lead to a global war and the fact that you unite all the tribes (in a positive ending), and then return home and continue endless fights, but without a special plot meaning . Nothing like?

Naturally, each subunit of the plot contains its own choice.

Here you can play the character and read new pieces of this interactive book. Yes, yes, this is an absolute repetition of the mechanics of the game book, only battles are more “computerized.”

So, the plot (and the setting) can be an end in itself. That is, to encourage players to play to the very, very end out of curiosity.

The plot can be a decoration. For example, humor in Galaxy on Fire is an optional thing, to play cool and so. But he is very happy throughout the story and decorates the game. It creates a special atmosphere of space hooliganism. Teaches us the features of our reckless character (and in role-playing games this unity is important to us). And, as a result, it offers strange strings for quests.

In more boring games, you often tolerate a monotonous piece for the sake of the plot. For example, in the last Fallout from the first person, something like this happened to me.

The plot can be learning. In the ingenious This War of Mine you have to constantly face the different horrors of war. Every day it gives you a choice - either to make your team worse or to do wrong. Take a look:

Like a blow to the head, right?

The game, of course, a little cunning. If the character was morally and physically in order (he kept good “karma”, that is, he did the necessary actions for the game to learn), then with him at the end of the plot everything will be in order. If not, it will be bad for him. The novel did a bad deed and will be punished:

And finally, the plot can be a mini-guide. That is, to put it in a gamedev-language, to shorten the action-result chain and give more concise sequences in response to the question “What should I do?”. In this regard, the plot, which is completely synergistic with the mechanics of the game, works well. Again, I will refer to board games as the closest example. In the Jackal you can put a pirate on the same cell, where there is another pirate. The latter in this case is transferred to your ship. We do not call this action "change the coordinates of the chips," but we say that you beat the enemy, and he went to the ship to lick his wounds. Or the goal of the game - to collect gold - directly follows from the fact that we are filibusters. Not noble environmentalists who came to this island to find crocodiles, but real pirates.

It is much easier to remember. In The Wizard of the Emerald City, children do not compare the position of their characters with the estimated function of time and play actions. They run away from Bastinda. It is clear that if an evil witch catches up with you - it is not very good. That gives rise to a children's scream of delight when Ellie steps forward. With an increase in the evaluation function, this would not have happened.

On the other hand, often for the sake of mechanics, you need to perform some kind of completely foolish actions - which destroys both the plot and the integrity of the game. For example, to collect some items at the levels when there is a war around. The main character is going to survive, and you make him climb for achivka every time - the plot immediately fray. For example, when in XCOM: Enemy Within they crammed up the “composition” collection (on ordinary missions, there were points where it was necessary to reach for a limited time), this, of course, remarkably changed the strategic depth. But it killed part of the plot, more precisely, made it somewhat absurd. That's because in the game world there was not enough convincing justification for these actions. Although, of course, a couple of sektoid interrogations and studies could clarify the situation if the game designer wanted.

Since the 80s, the number of holivars "plot against mechanics" has been growing in the game environment. A big open world against a closed one is essentially the same. If only because the infinite world cannot be completely written down by hands, that is, its plot will be automatic. Compare Daggerfall and Morrowind - there this difference is strongly noticeable. Or "Elite" and the same Galaxy on Fire. And so on.

Plot-oriented games as is

A small example from our desktop market. The game consists of mechanics and setting. It is the combination of these two components that determines the interestingness of the game. For example, I can say for sure that any game about minions worth up to 1,500 rubles will be sold with a circulation of at least 5,000 pieces from September to the end of December. The mechanics are not important there - the children will disassemble these soulless yellow creatures that they clogged the brain with. On the other hand, the mechanics of the “Wizard of the Emerald City” alone would provide well for 1/10 of sales. There was an important plot (as a reference to the book) and art. At the same time, the game itself turned out to be not a storyline, but a purely igromechanical and with high replayability.

On the other hand, the same little dandy or word guessing games have a finite capacity - sooner or later all the stories will be answered, and the words will be remembered. Scenario modules for AD & D can be run once (okay, a maximum of 2-3 in the same batch if you embed them as places on the map and take into account that each time the batches go "tangentially" or die). That is, the plot is almost always one-time or lower replayability. How Bioware solves this problem, you probably know very well - you blame them on what the world is worth, but you buy supplements.

The difference between a plot-oriented game and a mechanical one , in essence, is only in the fact that the first one is an evolving book, and the second one is an evolved desktop. Mass Effect - an interactive film - the evolution of the book. Fallout is a very complex book evolution. Arkanoid - well, you must have seen pinball machines, this is a direct ancestor. Tetris, "Colored lines" - all this is understandable.

And what about Vangers, FTL, Sword and Glory and other games where the plot is fucking important, but, it seems, this is not a book? Very simple - there is a competent alternation of only purely igromekhanicheskikh things like fights or traveling around the world and plot. The slaughter effect and replayability largely depend on the degree of quality of the weave. By the way, yes, the plot provides a long, but a single batch - therefore, even 100% mechanical games have one-time goals. Especially noteworthy is the goal of "pass - show a cartoon".

findings

- If you have a very strong atmospheric setting, the choice, of course, is the construction of a complex plot. If the setting is so-so or absent, the first role is mechanics. Although, of course, this division does not exist in reality - there are only priorities.

- Any game, especially on porting from a desktop or from platform to platform, can be made plot. Sometimes it matters. How to make purely mechanical things like chess subject? Simply: this is the Persian war in episodes (etudes). The best example, in my opinion, is the transfer of the Galaxy Trucker from desktop to application.

- It is very interesting to watch the dynamics of projects without a plot part (“Rusty Forest” and “Radiation Island”, “Sword & Glory”), which are gradually trying to acquire with this plot. As soon as it becomes clear and organically woven into the world - popularity is growing dramatically.

- With a good screenwriter, the essence of the game and its interestingness are transferred from the area of interaction with the computer to the area of internal dialogue. That is, the game is played in a person’s head: this is much more emotional. And the graphics here does not solve at all.

- Hence for the storyline, the beauty of the story itself often means more of the game. The practical conclusion is that the plot and elaboration of the details of the setting can partially compensate for some of the flaws.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/264623/

All Articles