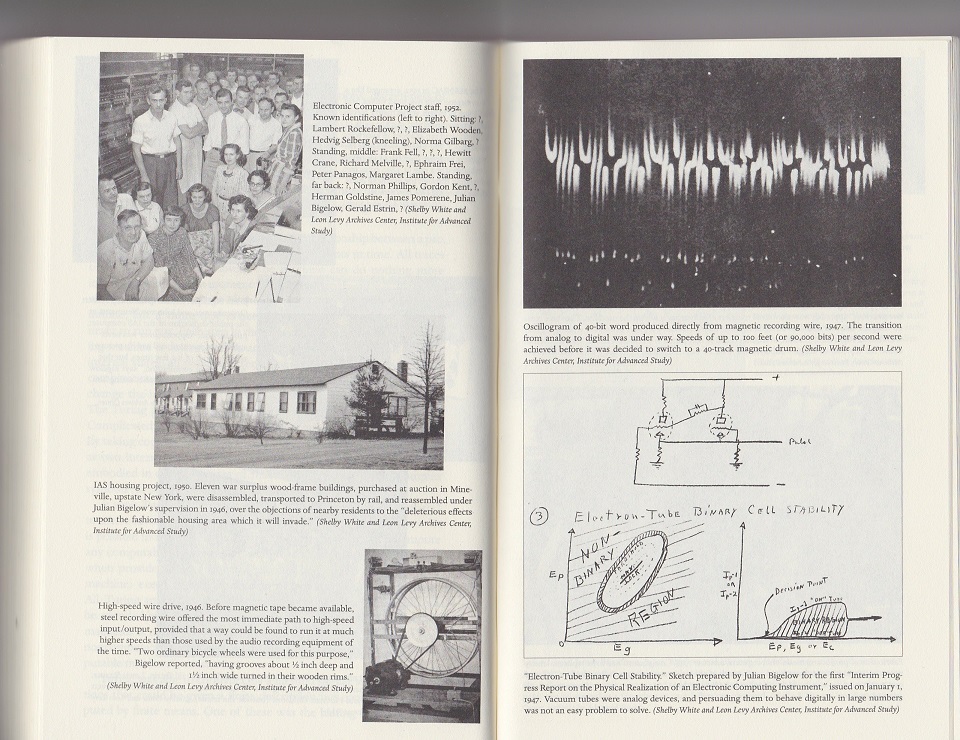

Turing's Cathedral: the origin of the digital universe

Hi, Habr!

I want to tell you about a great one, but in the Russian-language segment there is still a little-known book - Turing's Cathedral.

')

It describes the events of the forties and fifties of the twentieth century, which accompanied the development and construction of the world's first electronic digital general-purpose computers. But the history and design of these machines (ENIAC, EDVAC, and so on) have not surprised anyone for a long time, but the peculiarity of this book is that the author tried to recreate the events that took place at that time - all the small details, opinions, ideas and decisions of people involved in this project. To do this, he collected everything he could reach - books, articles, memoirs, letters, technical reports, debug listings, logbooks, personal notes, diaries and much more. Personally, at the turn of the century, he conducted dozens of interviews with eyewitnesses of those events and relatives of those who were no longer alive at that time.

It turned out to be a unique situation - Dyson was probably able to realize the last opportunity to get reliable and previously unpublished information at first hand. The result was a kind of epoch-making work, giving modern man the opportunity to plunge into an era when the concept of a “programmer” didn’t exist as such, and the principles of constructing computer technology that underlie almost all the devices currently in use have just begun to form.

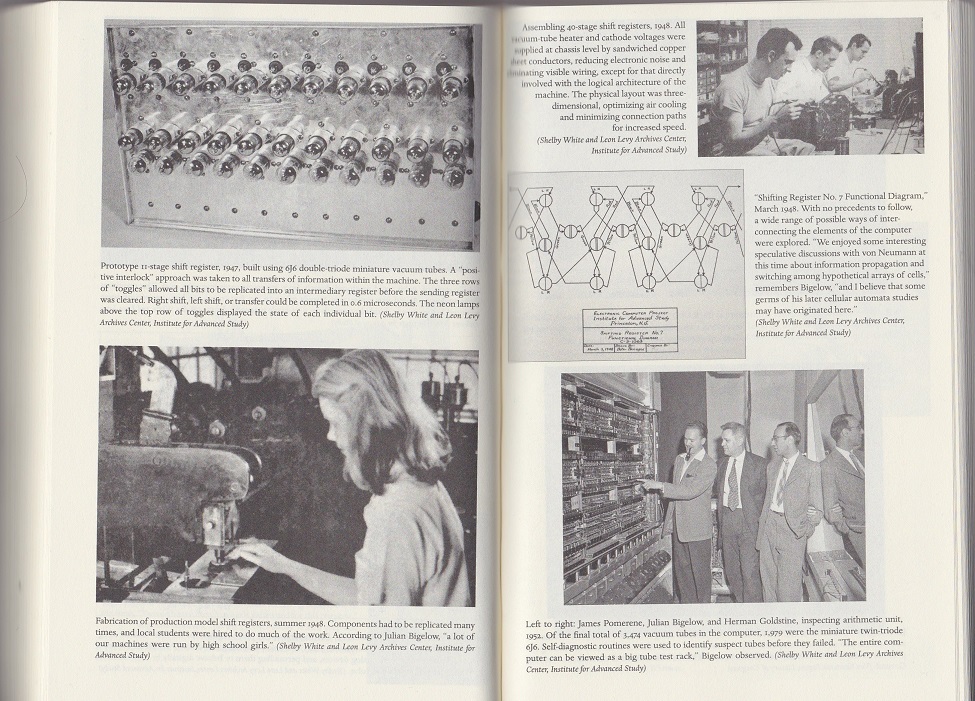

The book itself is not a reference to programming or circuit design. It contains 18 chapters, each of them is devoted to a separate story, and only four of them are devoted to purely engineering issues. There is the history of the emergence of Princeton University from the time of the first settlers who appeared in these lands, the foundations of mathematics and technology, which served as the foundation for building electronic computers, the social and political situation of that time, and the living conditions of people who participated in the creation of these machines in the middle of the 20th century . The second half of the book is devoted to tasks for which the first computers were used: from hydrogen bombs and the equations of propagation of a blast wave, to the movement of atmospheric fronts, the evolution of stars, and the self-reproduction of cells of organisms. To understand everything that is written in them, one must have a broad outlook or (and better and better) good knowledge of computer science and circuit design, automata theory, algorithms, and other branches of mathematics, physics, and even biology (plus knowledge of terminology in these areas in English - the book was published in 2012 and was not translated into Russian, as far as I know). The problem of solvability (the cornerstone Entscheidungsproblem), the principle of the shift register and the device of vacuum tubes, numerical solutions of differential equations and the Monte Carlo method, programming in machine codes and debugging of unstable iron - all of this is in excess.

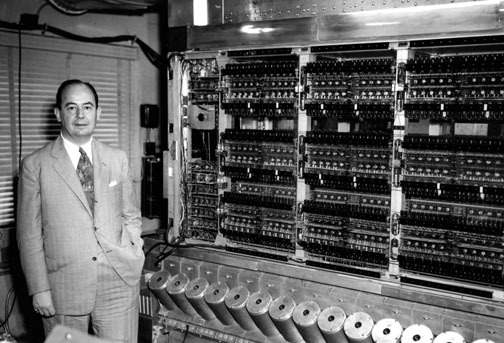

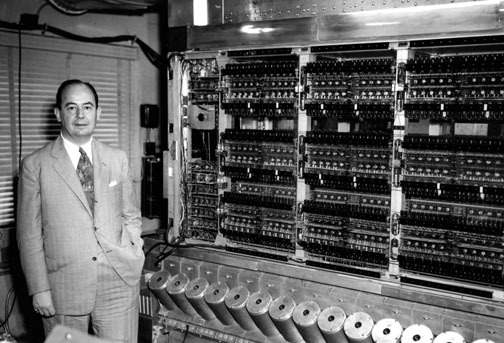

The red thread through almost all chapters is the personality of John von Neumann - an American mathematician of Hungarian origin. Pictured below is von Neumann with his MANIAC car in 1952 (photo by Alan Richards).

He literally broke into the field of computer technology - an area that at that time was left to the engineers and was considered by mathematicians and physicists to be inferior. Von Neumann saw this as an amazing potential for solving applied problems, and for several decades he became almost a central figure, a super star who had a great influence among engineers, military and government officials. A sort of Stephen Hawking or Herbert von Karajan in his field.

In this man, he, apparently, was ambiguous. For example, shortly after joining the team of engineers, von Neumann, on his own behalf, publishes in a large 101-page report the principles of building the EDVAC machine, developed long before his appearance in the project.

The report has become very popular, the principles are now known as von Neumann architecture, and the names of the real authors of these ideas (John Presper Eckert and John Mauchly) are known only to those who are interested in history. At the same time, the report was released as a scientific publication, which did not allow Eckert and Mauchly to patent their ideas any further, and they could not openly write about their developments due to security restrictions in wartime. But this did not prevent von Neumann from having to provide advisory services for IBM and other major organizations around the world for good fees. But he was, of course, a bright person, and who knows how the computing industry would have been without him. However, it is no less interesting how it would have happened if he had not suddenly died of cancer at the age of 52, at the peak of his fame, only 12 years after the successful start of the ENIAC computer. One of his last interests was a unified theory that describes self-replicating biological systems, technological systems, and any combinations thereof. Unfortunately, the theory remained unfinished.

The book is very interesting, even from a purely historical point of view. The story is replete with the names of great scientists: Gödel, Feynmann, Schwarzschild, Metropolis, Oppenheimer, Shannon, Baricelli and many others. All of them at one time or another were spinning around computers, so powerful it was a tool for conducting applied research. The Second World War made a huge contribution to the development of computing technology: as the Nazis captured Europe, most of the scientists were forced to flee, and the United States in this sense were as far from the scene of hostilities as possible. No matter how strange it may sound, von Neumann, Kurt Godel, Niels Bohr, Stanislav Ulam and many others - all of them were in the right place and at the right time mostly due to the war. Von Neumann personally played a significant role in this. He spent a lot of energy to provide him with work (that is, financing) the most interesting personalities to him. Yes, they would have shown their talents in their own countries, but hardly von Neumann achieved the same results in such a short time without his team of engineers led by Biglow, Ulam would not have brought his theory of thermonuclear weapons to the end without Teller, and that’s all together they would have done little without the US military, who are ready to generously sponsor all this. Such a concentration of brilliant people in the right place simply could not go unnoticed.

It is worth noting that at times the book was quite hard to read, especially at first. In an effort to create as complete a picture as possible, the author accompanies his stories with a rather detailed biography of all the people who have made any significant contribution to the development of the described area. Also, part of the chapters essentially describes the same time, but from different points of view and sides, which is not at first obvious behind a huge list of names, places, events and dates. The chronology in the head begins to line up only in essence by the middle of the book. So the book, apparently, must be read a second time - the first time it’s more interesting to read the story itself, and not the names and professions of the grandparents of the heroes, but the second time, already knowing all the actors and their contribution, it would surely be everything was perceived to another.

The book concludes with reflections on what awaits humanity and computing technology in the future. Social networks and Internet search engines that integrate information about people around the world, and are already operating according to their own rules, are not always completely understandable by the people who created them - these are supra-computer organisms that implement a kind of analog, continuous, “computation”, digital which von Neumann wrote a lot at the end of his life. Who knows what it will become in 60 years.

Total, the book will appeal to those who are interested in the history of IT development, as well as the device and application of the first electronic computers. Good knowledge of English is required both in general and in the technical field (upper intermidiate / advanced or a good dictionary at hand and a lot of patience). Well, if someone goes to the feat and translates it into Russian with high quality, there will be no price for it at all.

I want to tell you about a great one, but in the Russian-language segment there is still a little-known book - Turing's Cathedral.

')

It describes the events of the forties and fifties of the twentieth century, which accompanied the development and construction of the world's first electronic digital general-purpose computers. But the history and design of these machines (ENIAC, EDVAC, and so on) have not surprised anyone for a long time, but the peculiarity of this book is that the author tried to recreate the events that took place at that time - all the small details, opinions, ideas and decisions of people involved in this project. To do this, he collected everything he could reach - books, articles, memoirs, letters, technical reports, debug listings, logbooks, personal notes, diaries and much more. Personally, at the turn of the century, he conducted dozens of interviews with eyewitnesses of those events and relatives of those who were no longer alive at that time.

It turned out to be a unique situation - Dyson was probably able to realize the last opportunity to get reliable and previously unpublished information at first hand. The result was a kind of epoch-making work, giving modern man the opportunity to plunge into an era when the concept of a “programmer” didn’t exist as such, and the principles of constructing computer technology that underlie almost all the devices currently in use have just begun to form.

The book itself is not a reference to programming or circuit design. It contains 18 chapters, each of them is devoted to a separate story, and only four of them are devoted to purely engineering issues. There is the history of the emergence of Princeton University from the time of the first settlers who appeared in these lands, the foundations of mathematics and technology, which served as the foundation for building electronic computers, the social and political situation of that time, and the living conditions of people who participated in the creation of these machines in the middle of the 20th century . The second half of the book is devoted to tasks for which the first computers were used: from hydrogen bombs and the equations of propagation of a blast wave, to the movement of atmospheric fronts, the evolution of stars, and the self-reproduction of cells of organisms. To understand everything that is written in them, one must have a broad outlook or (and better and better) good knowledge of computer science and circuit design, automata theory, algorithms, and other branches of mathematics, physics, and even biology (plus knowledge of terminology in these areas in English - the book was published in 2012 and was not translated into Russian, as far as I know). The problem of solvability (the cornerstone Entscheidungsproblem), the principle of the shift register and the device of vacuum tubes, numerical solutions of differential equations and the Monte Carlo method, programming in machine codes and debugging of unstable iron - all of this is in excess.

The red thread through almost all chapters is the personality of John von Neumann - an American mathematician of Hungarian origin. Pictured below is von Neumann with his MANIAC car in 1952 (photo by Alan Richards).

He literally broke into the field of computer technology - an area that at that time was left to the engineers and was considered by mathematicians and physicists to be inferior. Von Neumann saw this as an amazing potential for solving applied problems, and for several decades he became almost a central figure, a super star who had a great influence among engineers, military and government officials. A sort of Stephen Hawking or Herbert von Karajan in his field.

In this man, he, apparently, was ambiguous. For example, shortly after joining the team of engineers, von Neumann, on his own behalf, publishes in a large 101-page report the principles of building the EDVAC machine, developed long before his appearance in the project.

The report has become very popular, the principles are now known as von Neumann architecture, and the names of the real authors of these ideas (John Presper Eckert and John Mauchly) are known only to those who are interested in history. At the same time, the report was released as a scientific publication, which did not allow Eckert and Mauchly to patent their ideas any further, and they could not openly write about their developments due to security restrictions in wartime. But this did not prevent von Neumann from having to provide advisory services for IBM and other major organizations around the world for good fees. But he was, of course, a bright person, and who knows how the computing industry would have been without him. However, it is no less interesting how it would have happened if he had not suddenly died of cancer at the age of 52, at the peak of his fame, only 12 years after the successful start of the ENIAC computer. One of his last interests was a unified theory that describes self-replicating biological systems, technological systems, and any combinations thereof. Unfortunately, the theory remained unfinished.

The book is very interesting, even from a purely historical point of view. The story is replete with the names of great scientists: Gödel, Feynmann, Schwarzschild, Metropolis, Oppenheimer, Shannon, Baricelli and many others. All of them at one time or another were spinning around computers, so powerful it was a tool for conducting applied research. The Second World War made a huge contribution to the development of computing technology: as the Nazis captured Europe, most of the scientists were forced to flee, and the United States in this sense were as far from the scene of hostilities as possible. No matter how strange it may sound, von Neumann, Kurt Godel, Niels Bohr, Stanislav Ulam and many others - all of them were in the right place and at the right time mostly due to the war. Von Neumann personally played a significant role in this. He spent a lot of energy to provide him with work (that is, financing) the most interesting personalities to him. Yes, they would have shown their talents in their own countries, but hardly von Neumann achieved the same results in such a short time without his team of engineers led by Biglow, Ulam would not have brought his theory of thermonuclear weapons to the end without Teller, and that’s all together they would have done little without the US military, who are ready to generously sponsor all this. Such a concentration of brilliant people in the right place simply could not go unnoticed.

It is worth noting that at times the book was quite hard to read, especially at first. In an effort to create as complete a picture as possible, the author accompanies his stories with a rather detailed biography of all the people who have made any significant contribution to the development of the described area. Also, part of the chapters essentially describes the same time, but from different points of view and sides, which is not at first obvious behind a huge list of names, places, events and dates. The chronology in the head begins to line up only in essence by the middle of the book. So the book, apparently, must be read a second time - the first time it’s more interesting to read the story itself, and not the names and professions of the grandparents of the heroes, but the second time, already knowing all the actors and their contribution, it would surely be everything was perceived to another.

The book concludes with reflections on what awaits humanity and computing technology in the future. Social networks and Internet search engines that integrate information about people around the world, and are already operating according to their own rules, are not always completely understandable by the people who created them - these are supra-computer organisms that implement a kind of analog, continuous, “computation”, digital which von Neumann wrote a lot at the end of his life. Who knows what it will become in 60 years.

Total, the book will appeal to those who are interested in the history of IT development, as well as the device and application of the first electronic computers. Good knowledge of English is required both in general and in the technical field (upper intermidiate / advanced or a good dictionary at hand and a lot of patience). Well, if someone goes to the feat and translates it into Russian with high quality, there will be no price for it at all.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/261033/

All Articles