A simple explanation of the movement of money in the banking system

From the translator: In recent months, the news of the financial sphere has firmly entered the lives of many people. One of the recent themes is the possible disconnection of Russia from the SWIFT system . The threat looks very serious, but what really threatens the country if events develop according to this scenario? Our today's material is designed to help deal with how things work in the global world of finance.

Last week [the article was published in November 2013] Twitter went insane due to the fact that someone had transferred almost $ 150 million per transaction in cryptocurrency. The appearance of such a tweet was in the order of things:

')

A transaction of 194,993 bitcoins worth $ 147 million gives rise to many secrets and speculations.

There were a lot of comments about how expensive and difficult it would be to implement in the ordinary banking system, and it is quite possible that this is the case. But at the same time I paid attention to the following: I know from my own experience that almost no one understands how payment systems actually work. That is: when you “transfer” money to a supplier or “make a payment” to someone's account, how does money transfer from your account to the accounts of others ?

With the help of this article, I will try to change the situation and carry out a simple, but, I hope, not too simplistic, analysis in this area.

I think, first of all, you need to understand that bank deposits are liabilities of [the bank before you] . When you put money in the bank, in fact you do not have a deposit. This is not a money bag on which your name is written. Instead, you loan this money to a bank. He owes them to you. This money becomes one of the obligations of the bank. That is why we say that our money is in a credit account: we have provided a loan to the bank. Similarly, if you exceed the loan and you owe it to the bank, this becomes your obligation and their asset. To understand how money moves, it is important to understand that each record in the accounting report can be viewed from these two points of view.

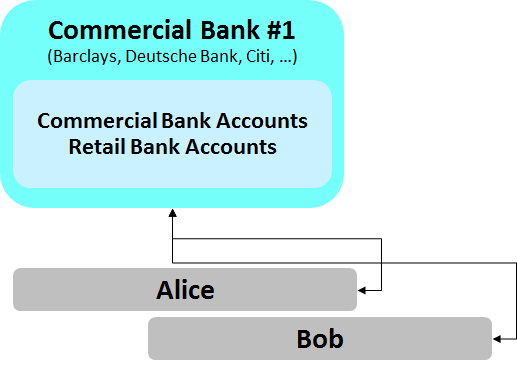

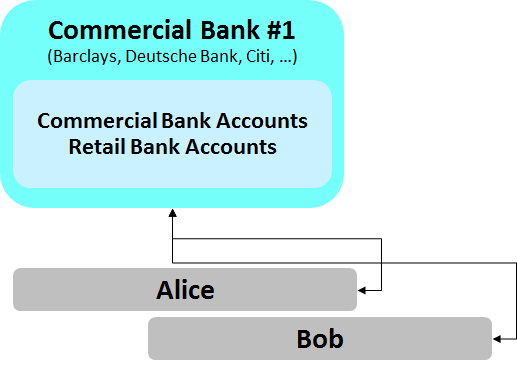

Let's start with a simple example. Imagine that your name is Alice , and you are a customer of, say, Barclays Bank. You owe 10 pounds to your friend named Bob , who also uses Barclays. Bob is easy to pay: you tell the bank about your intentions, he withdraws money from your account and pays 10 pounds to your friend's account. The procedure is carried out electronically through Barclays automated banking system, everything is extremely simple: the money neither goes to the bank, nor is it withdrawn from it; there is only an update of the system of accounts. The bank owes you 10 pounds less and Bob 10 pounds more. Everything is balanced, and everything happens inside the bank: they say that the transaction is “fixed” in the bank’s books of account. This is presented in the diagram below: only three parties take part - you, Bob and Barclays. (Naturally, the same analysis can be carried out if you carry out a transaction in euros through Deutsche Bank or in dollars through Citi, etc.)

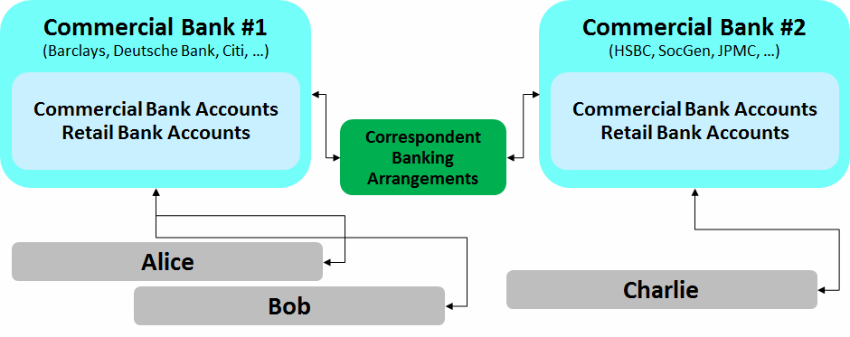

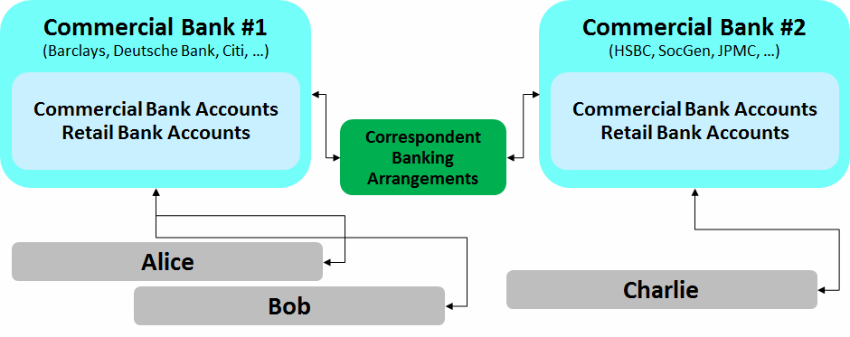

Here the situation is more interesting. Imagine that you need to pay a certain Charlie , an HSBC client. There is a problem: it is easy for Barclays to take 10 pounds from your account, but how can they convince HSBC to increase Charlie 's account by 10 pounds? Why should the HSBC bank agree to owe Charlie more than before? They are not a charitable organization! Clearly, the answer is that if we want HSBC to owe Charlie a little more, they need to be owed to someone else a little less .

What should this “other” be? This is definitely not Alice: if you remember, she has nothing to do with HSBC. By the method of exclusion, it turns out that the only possible option is Barclays. And the first thing that comes to mind is this: what if HSBC opens an account with Barclays and Barclays opens an account with HSBC ? Each of the banks could open an account in another bank and regulate these accounts to solve such problems ...

Here's how to proceed:

Everything is balanced for Barclays and HSBC. Before that, Barclays owed 10 pounds to Alice, now they owe 10 pounds to HSBC. HSBC had been nil before, now they owe 10 pounds to Charlie, and Barclays owe 10 pounds to them.

Such a payment processing model (and its more complex varieties) is known as the activity of banks on the basis of correspondent relations. Graphically, it can be represented like the diagram below. The previous scheme is taken as the basis and the second commercial bank is added; It is important to note that the presence of correspondent relations allows banks to facilitate the payment of payments to relevant customers.

The scheme works quite well, but there are some difficulties:

In the future we will talk about some of these difficulties.

[Note: this is not what is happening today * actually *, because the systems described below are used instead, but I thought it was logical to start the story in such a way that you could clearly imagine what is happening]

As a rule, during the discussion of payment systems there will necessarily be a person who will wave his hands, shout “SWIFT” and assume that the issue has been resolved. In my opinion, this only confirms that such people probably don’t understand what they are talking about.

The SWIFT network allows banks to freely exchange e-mails with each other. One type of message that is supported by the SWIFT network is MT103. MT103 allows one bank to give instructions to another bank so that the latter transfers the amount to one of its customers' accounts, while the same amount is debited from the account of the organization sending the message at the bank accepting it so that everything is balanced. You can imagine how the message MT103 would apply in the case described in the previous part.

Thus, as a result of sending the message MT103 in the SWIFT network, the money is “forwarded” between two banks, but it is especially important to understand what is actually happening: the message over the SWIFT network is just an indication; cash flows are made when they are transferred to certain accounts and depend on banks that have accounts with other banks (directly or through intermediary banks). Just waving your arms and shouting: “SWIFT!” Means hiding these difficulties, and therefore hinder understanding of the system.

Stop ... Let's first briefly repeat.

We have shown that transferring money between two account holders in the same bank is not difficult.

We also showed how to transfer money between two account holders in different banks in a rather clever way: to make each bank open an account in another bank.

In addition, we discussed how electronic messaging systems like SWIFT can control the flow of information between two banks and ensure that transfers are fast, reliable and cheap.

But we have something else to discuss ... since such serious questions arise as counterparty risk, liquidity and expenses.

First consider liquidity and expenses .

First, you need to consider that the SWIFT network costs money. If Barclays needed to send a message over the SWIFT network to the HSBC bank every time you want to transfer 10 pounds to Charlie’s account, you would soon find out significant costs in your statement. But worse, a more serious problem arises - liquidity .

Consider how much money Barclays would need to be in touch with all correspondent banks every day if the system described earlier was put into practice. They would need to have large amounts in their accounts at all other banks in case one of their clients wants to transfer money to an HSBC, Lloyds, Co-op customer account or anywhere else. This cash could be invested, lent or otherwise spent.

But a very interesting thought may arise: in the end, a Barclays client will most likely transfer money to an HSBC client account with the same degree of probability that an HSBC client will transfer money to a Barclays client account at a specific point in time.

So what if we continued to track all the numerous payments during the day and would only record the difference ? With this approach, each of the banks could have much less cash on each of the correspondent accounts, and each could invest their money more efficiently, while reducing costs and (hopefully) sending some of this money to your bank. Such reasoning led to the emergence of deferred net settlement systems (CONP). In the UK, such a system is BACS, and in any country you can find its analogues. In such systems, they do not exchange messages through the SWIFT network. Instead, messages (or files) fall into a central “clearing” system (such as BACS), which tracks all payments and then, within a specified time, calculates the net amount each bank owes to any other bank. After that, they conduct certain transactions among themselves (possibly transferring money to / from accounts that each of the banks has at another bank) or use the RTGS system described below.

This method significantly reduces the cost and liquidity requirements and complements our scheme with one more unit:

It is worth paying attention to the fact that in the same way (as CONR) one can describe the mechanisms of using credit cards and even PayPal: they all are characterized by the process of calculating internal transaction costs, which results in only the net amount determined for large banks.

But even with this approach, a potentially more serious problem arises - the loss of completeness of the calculation . You can send your payment instructions in the morning, but the receiving bank will not be able to receive (net) funds until a certain point.

Therefore, the receiving bank has to wait for the receipt of a (net) settlement of the account in case of possible bankruptcy of the sender during the transfer: it would be rash to transfer funds to the receiving party in advance. As a result, a delay occurs.

On the other hand, it would be possible to take the risk and in case of a problem, cancel the transaction. But then the settlement would never be considered “completed”, and in this case the recipient could not have expected to receive this money before a certain date.

This is where all the pieces of the puzzle come together. None of the approaches discussed earlier can be applied in situations where you need to be absolutely sure that the payment will be made quickly and cannot be canceled even if the sending bank goes bust . You really need this kind of guarantee, for example, if you intend to create a settlement system for securities transactions: no one will give you $ 150 million in bonds or shares, if there is a risk that these $ 150 million will not be paid, or they will not be returned!

A system is needed, like the first one we’ve considered (Alice transfers money to Bob’s account at the same bank) - because everything is really fast in her — but that will work with more than one bank participating. The multilateral interbank system, considered earlier, seems to be working, but it becomes quite confusing when transferring sufficiently large amounts and if there is a likelihood that a particular bank may go bankrupt.

Now, if banks could have accounts in such a bank that cannot go bankrupt ... a kind of bank that would be in the very center of the system. You can think of a name for him. Let's call it the central bank !

Following this logic, the idea of a gross settlement system in real time arises [eng. Real-Time Gross Settlement system, RTGS].

If all the largest banks in a country have accounts in the central bank, they can transfer money from one bank to another, simply giving instructions to the central bank to withdraw funds from one account and transfer them to another. For this purpose, the systems CHAPS, FedWire and Target 2 are intended, which are engaged in the transfer of pounds, dollars and euros, respectively. These systems carry out cash flow in real time between accounts that banks have in the respective central bank. So, this is the system:

This system completes our scheme:

Well, that reminded. Now the question arises: is it possible to put Bitcoin in this model?

It seems to me that Bitcoin is very much like the RTGS system. It does not include debt accounting, (obviously) there are no correspondent relations between banks, and all calculations are gross, completed.

However, the “traditional” financial landscape is interesting because most retail transactions today are not carried out through the RTGS system. For example, direct electronic payments between residents of the UK are made through the system of accelerated payment FPS [English. Faster Payments system], which performs counter claims several times a day, not instantly. Why is that? I would say, because, first of all, FPS is (almost) free, while the cost of payments in the CHAPS system is 25 pounds. Many customers would probably use the RTGS system if it were just as convenient and cheap.

Therefore, my unanswered question is: will the Bitcoin payment system remain just like the traditional RTGS, which performs only the most significant transfers? Or will changes in the core network (block size restrictions, channels for micropayments, etc.) occur and will occur fairly quickly with an increase in the volume of transactions, allowing the system to remain available for both more significant and less significant payments?

I think the question still remains open: I am sure that Bitcoin will change the world, but at the same time I am not so sure that we will live in a world where every transaction carried out with the help of the Bitcoin network “passes” through the Blockchain database.

Last week [the article was published in November 2013] Twitter went insane due to the fact that someone had transferred almost $ 150 million per transaction in cryptocurrency. The appearance of such a tweet was in the order of things:

')

A transaction of 194,993 bitcoins worth $ 147 million gives rise to many secrets and speculations.

There were a lot of comments about how expensive and difficult it would be to implement in the ordinary banking system, and it is quite possible that this is the case. But at the same time I paid attention to the following: I know from my own experience that almost no one understands how payment systems actually work. That is: when you “transfer” money to a supplier or “make a payment” to someone's account, how does money transfer from your account to the accounts of others ?

With the help of this article, I will try to change the situation and carry out a simple, but, I hope, not too simplistic, analysis in this area.

First we find the points of contact

I think, first of all, you need to understand that bank deposits are liabilities of [the bank before you] . When you put money in the bank, in fact you do not have a deposit. This is not a money bag on which your name is written. Instead, you loan this money to a bank. He owes them to you. This money becomes one of the obligations of the bank. That is why we say that our money is in a credit account: we have provided a loan to the bank. Similarly, if you exceed the loan and you owe it to the bank, this becomes your obligation and their asset. To understand how money moves, it is important to understand that each record in the accounting report can be viewed from these two points of view.

Transfer of funds to the client’s account of the same bank

Let's start with a simple example. Imagine that your name is Alice , and you are a customer of, say, Barclays Bank. You owe 10 pounds to your friend named Bob , who also uses Barclays. Bob is easy to pay: you tell the bank about your intentions, he withdraws money from your account and pays 10 pounds to your friend's account. The procedure is carried out electronically through Barclays automated banking system, everything is extremely simple: the money neither goes to the bank, nor is it withdrawn from it; there is only an update of the system of accounts. The bank owes you 10 pounds less and Bob 10 pounds more. Everything is balanced, and everything happens inside the bank: they say that the transaction is “fixed” in the bank’s books of account. This is presented in the diagram below: only three parties take part - you, Bob and Barclays. (Naturally, the same analysis can be carried out if you carry out a transaction in euros through Deutsche Bank or in dollars through Citi, etc.)

But what happens when you need to transfer money to the account of a client of another bank?

Here the situation is more interesting. Imagine that you need to pay a certain Charlie , an HSBC client. There is a problem: it is easy for Barclays to take 10 pounds from your account, but how can they convince HSBC to increase Charlie 's account by 10 pounds? Why should the HSBC bank agree to owe Charlie more than before? They are not a charitable organization! Clearly, the answer is that if we want HSBC to owe Charlie a little more, they need to be owed to someone else a little less .

What should this “other” be? This is definitely not Alice: if you remember, she has nothing to do with HSBC. By the method of exclusion, it turns out that the only possible option is Barclays. And the first thing that comes to mind is this: what if HSBC opens an account with Barclays and Barclays opens an account with HSBC ? Each of the banks could open an account in another bank and regulate these accounts to solve such problems ...

Here's how to proceed:

- Barclays can take £ 10 off Alice

- Barclays can then add £ 10 to an HSBC account opened with Barclays.

- After that, Barclays can send a message to HSBC that they have increased their bill by 10 pounds and would like those in turn to increase Charlie’s bill by 10 pounds.

- HSBC would receive this message and, knowing that they have an extra 10 pounds on deposit at Barclays, could increase Charlie's bill.

Everything is balanced for Barclays and HSBC. Before that, Barclays owed 10 pounds to Alice, now they owe 10 pounds to HSBC. HSBC had been nil before, now they owe 10 pounds to Charlie, and Barclays owe 10 pounds to them.

Such a payment processing model (and its more complex varieties) is known as the activity of banks on the basis of correspondent relations. Graphically, it can be represented like the diagram below. The previous scheme is taken as the basis and the second commercial bank is added; It is important to note that the presence of correspondent relations allows banks to facilitate the payment of payments to relevant customers.

The scheme works quite well, but there are some difficulties:

- Most obviously, this is possible only if the two banks are in direct communication with each other. Otherwise, either you will not be able to make a payment, or you will need to make a route through the third (or fourth!) Bank until you complete the journey from point A to point B. Of course, this increases the costs and degree of difficulty. (Some experts limit the use of the concept of "correspondent relations" to situations involving different currencies, but it seems to me that this term is useful to use even in simpler situations)

- More disturbing is the fact that it is also risky. Take a look at the situation from the position of HSBC bank. The result of the payment they made was increased vulnerability on the part of Barclays. In our example, only 10 pounds. But imagine that the amount was 150 million pounds, and the correspondent bank was not Barclays, but a smaller and possibly less reliable organization: HSBC would have been in big trouble if the bank had been ruined. One solution is to make a small change in the model itself: instead of transferring funds to the HSBC account, Barclays could ask HSBC to write off money from the account Barclays uses. Then there would be no need for large interbank settlements. However, with this approach, other difficulties arise and, in one way or another, the interdependence inherent in this model is a rather large problem.

In the future we will talk about some of these difficulties.

[Note: this is not what is happening today * actually *, because the systems described below are used instead, but I thought it was logical to start the story in such a way that you could clearly imagine what is happening]

Wait ... why complicate things? Can't you just use the SWIFT system [Eng. Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications - International Interbank Information Transmission and Payment System] and be done with it?

As a rule, during the discussion of payment systems there will necessarily be a person who will wave his hands, shout “SWIFT” and assume that the issue has been resolved. In my opinion, this only confirms that such people probably don’t understand what they are talking about.

The SWIFT network allows banks to freely exchange e-mails with each other. One type of message that is supported by the SWIFT network is MT103. MT103 allows one bank to give instructions to another bank so that the latter transfers the amount to one of its customers' accounts, while the same amount is debited from the account of the organization sending the message at the bank accepting it so that everything is balanced. You can imagine how the message MT103 would apply in the case described in the previous part.

Thus, as a result of sending the message MT103 in the SWIFT network, the money is “forwarded” between two banks, but it is especially important to understand what is actually happening: the message over the SWIFT network is just an indication; cash flows are made when they are transferred to certain accounts and depend on banks that have accounts with other banks (directly or through intermediary banks). Just waving your arms and shouting: “SWIFT!” Means hiding these difficulties, and therefore hinder understanding of the system.

Okay ... I see. And what about ACH, EURO1, Faster Payments, BACS, CHAPS, FedWire, Target2 and so on and so on ????

Stop ... Let's first briefly repeat.

We have shown that transferring money between two account holders in the same bank is not difficult.

We also showed how to transfer money between two account holders in different banks in a rather clever way: to make each bank open an account in another bank.

In addition, we discussed how electronic messaging systems like SWIFT can control the flow of information between two banks and ensure that transfers are fast, reliable and cheap.

But we have something else to discuss ... since such serious questions arise as counterparty risk, liquidity and expenses.

First consider liquidity and expenses .

We need to solve the problem of liquidity and expenses.

First, you need to consider that the SWIFT network costs money. If Barclays needed to send a message over the SWIFT network to the HSBC bank every time you want to transfer 10 pounds to Charlie’s account, you would soon find out significant costs in your statement. But worse, a more serious problem arises - liquidity .

Consider how much money Barclays would need to be in touch with all correspondent banks every day if the system described earlier was put into practice. They would need to have large amounts in their accounts at all other banks in case one of their clients wants to transfer money to an HSBC, Lloyds, Co-op customer account or anywhere else. This cash could be invested, lent or otherwise spent.

But a very interesting thought may arise: in the end, a Barclays client will most likely transfer money to an HSBC client account with the same degree of probability that an HSBC client will transfer money to a Barclays client account at a specific point in time.

So what if we continued to track all the numerous payments during the day and would only record the difference ? With this approach, each of the banks could have much less cash on each of the correspondent accounts, and each could invest their money more efficiently, while reducing costs and (hopefully) sending some of this money to your bank. Such reasoning led to the emergence of deferred net settlement systems (CONP). In the UK, such a system is BACS, and in any country you can find its analogues. In such systems, they do not exchange messages through the SWIFT network. Instead, messages (or files) fall into a central “clearing” system (such as BACS), which tracks all payments and then, within a specified time, calculates the net amount each bank owes to any other bank. After that, they conduct certain transactions among themselves (possibly transferring money to / from accounts that each of the banks has at another bank) or use the RTGS system described below.

This method significantly reduces the cost and liquidity requirements and complements our scheme with one more unit:

It is worth paying attention to the fact that in the same way (as CONR) one can describe the mechanisms of using credit cards and even PayPal: they all are characterized by the process of calculating internal transaction costs, which results in only the net amount determined for large banks.

But even with this approach, a potentially more serious problem arises - the loss of completeness of the calculation . You can send your payment instructions in the morning, but the receiving bank will not be able to receive (net) funds until a certain point.

Therefore, the receiving bank has to wait for the receipt of a (net) settlement of the account in case of possible bankruptcy of the sender during the transfer: it would be rash to transfer funds to the receiving party in advance. As a result, a delay occurs.

On the other hand, it would be possible to take the risk and in case of a problem, cancel the transaction. But then the settlement would never be considered “completed”, and in this case the recipient could not have expected to receive this money before a certain date.

Is it possible to achieve both completeness of settlement and zero counterparty risk?

This is where all the pieces of the puzzle come together. None of the approaches discussed earlier can be applied in situations where you need to be absolutely sure that the payment will be made quickly and cannot be canceled even if the sending bank goes bust . You really need this kind of guarantee, for example, if you intend to create a settlement system for securities transactions: no one will give you $ 150 million in bonds or shares, if there is a risk that these $ 150 million will not be paid, or they will not be returned!

A system is needed, like the first one we’ve considered (Alice transfers money to Bob’s account at the same bank) - because everything is really fast in her — but that will work with more than one bank participating. The multilateral interbank system, considered earlier, seems to be working, but it becomes quite confusing when transferring sufficiently large amounts and if there is a likelihood that a particular bank may go bankrupt.

Now, if banks could have accounts in such a bank that cannot go bankrupt ... a kind of bank that would be in the very center of the system. You can think of a name for him. Let's call it the central bank !

Following this logic, the idea of a gross settlement system in real time arises [eng. Real-Time Gross Settlement system, RTGS].

If all the largest banks in a country have accounts in the central bank, they can transfer money from one bank to another, simply giving instructions to the central bank to withdraw funds from one account and transfer them to another. For this purpose, the systems CHAPS, FedWire and Target 2 are intended, which are engaged in the transfer of pounds, dollars and euros, respectively. These systems carry out cash flow in real time between accounts that banks have in the respective central bank. So, this is the system:

- Gross - no accounting of debts (otherwise the system could not be instant)

- Calculations - the presence of completion; no refund

- In real time - calculations are carried out instantly.

This system completes our scheme:

I thought this article was somehow related to bitcoin

Well, that reminded. Now the question arises: is it possible to put Bitcoin in this model?

It seems to me that Bitcoin is very much like the RTGS system. It does not include debt accounting, (obviously) there are no correspondent relations between banks, and all calculations are gross, completed.

However, the “traditional” financial landscape is interesting because most retail transactions today are not carried out through the RTGS system. For example, direct electronic payments between residents of the UK are made through the system of accelerated payment FPS [English. Faster Payments system], which performs counter claims several times a day, not instantly. Why is that? I would say, because, first of all, FPS is (almost) free, while the cost of payments in the CHAPS system is 25 pounds. Many customers would probably use the RTGS system if it were just as convenient and cheap.

Therefore, my unanswered question is: will the Bitcoin payment system remain just like the traditional RTGS, which performs only the most significant transfers? Or will changes in the core network (block size restrictions, channels for micropayments, etc.) occur and will occur fairly quickly with an increase in the volume of transactions, allowing the system to remain available for both more significant and less significant payments?

I think the question still remains open: I am sure that Bitcoin will change the world, but at the same time I am not so sure that we will live in a world where every transaction carried out with the help of the Bitcoin network “passes” through the Blockchain database.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/253675/

All Articles