Developing a simple game in Code :: blocks using Direct3D 9

I want to talk about my first experience in game dev. Immediately it is worth making a reservation that the article will be purely technical, since my goal was just to gain skills in developing graphic applications using Direct3D, without involving high-level development tools for games like Unity. Accordingly, there will be no talk about the introduction, monetization and promotion of the game. The article focuses on newcomers to programming Direct3D applications, as well as simply on people interested in the key mechanisms for the operation of such applications. Also at the end I cite a list of references on game development, carefully selected by me from more than a hundred books on game programming and computer graphics.

So, in my free time I decided to explore the popular graphic API. After reading a few books and examining a bunch of examples and tutorials (including from the DirectX SDK), I realized that the very moment had come when it was worth trying your own efforts. The main problem was that most of the existing examples simply demonstrate this or that API capability and are implemented procedurally in almost one cpp-file, and even using the DXUT wrapper, and do not give an idea of what structure the final application should have what classes need to be designed and how it should all interact with each other, so that everything is beautiful, readable and efficiently work. This disadvantage also applies to books on Direct3D: for example, for many newbies, it is not obvious that render states do not always need to be updated when every frame is drawn, and also that most heavy operations (such as filling the vertex buffer) should be performed just once when the application is initialized (or when the game level is loaded).

The first thing I needed was to decide on the very idea of the game. The old game from 1992 under MS-DOS came to mind, which I think is familiar to many. This is a logical game Lines of the company Gamos.

Well, the challenge is accepted. Here is what we have:

Now let's look from the point of view of the Direct3D application:

In fact, the points listed above are a pathetic likeness of a document called a design project. I strongly recommend, before starting development, to paint it in every detail, print it out and keep it in front of your eyes! Looking ahead, I immediately show a demo video for clarity of the implementation of the points (by the way, the video was recorded using the ezvid program, so do not be intimidated by their splash screen in the beginning):

')

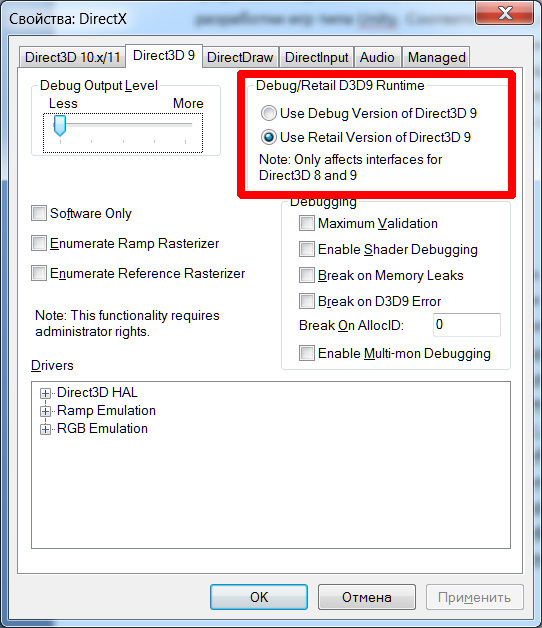

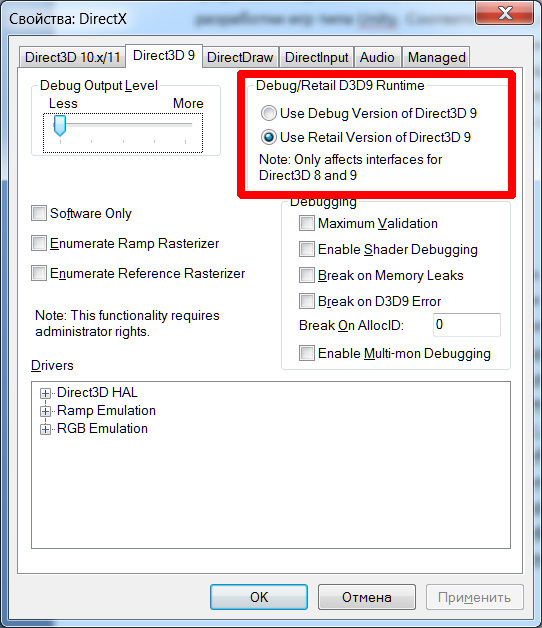

So far I have not mentioned which tools were used. First, you need the DirectX software development kit (SDK), always available for free download on the Microsoft website: DirectX SDK . If you are going to use the version of Direct3D 9, like me, then after installation you need to open the DirectX Control Panel through the main menu and on the Direct3D 9 tab choose which version of libraries will be used during assembly - retail or debug (this affects whether Direct3D will report debugger on the results of its activities):

Why Direct3D version 9? Because this is the latest version, where there is still a fixed function pipeline, that is, a fixed graphics pipeline, which includes, for example, the functions of lighting calculation, vertex processing, mixing, and so on. Starting from the 10th version, developers are invited to independently implement these functions in shaders, which is an indisputable advantage, but, in my opinion, it is difficult to understand at the first experiments with Direct3D.

Why Code :: blocks? It was probably silly to use a cross-platform IDE to develop an application using a non-cross-platform API. Just Code :: blocks takes up several times less space than Visual Studio, which turned out to be very relevant for my country PC.

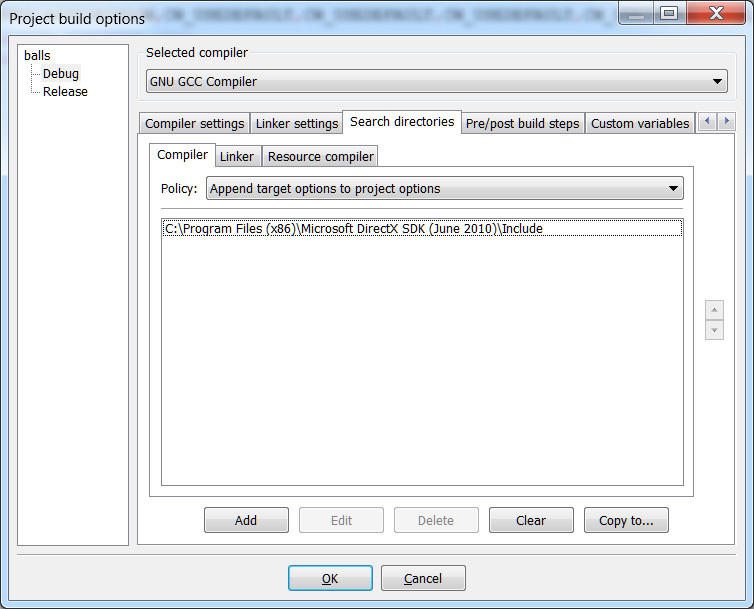

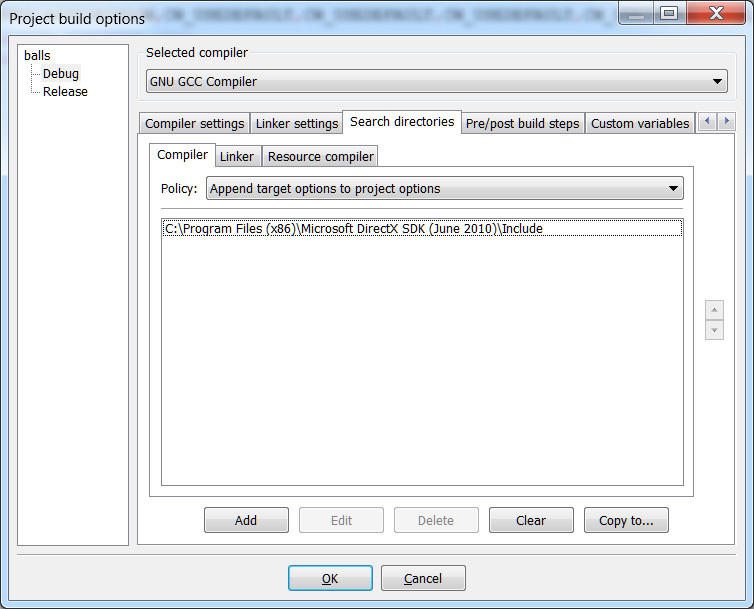

Starting development with Direct3D was very simple. I created an empty project in Code :: blocks, then I had to do two things in the build options:

1) On the search directories tab and the compiler subtab, add the path to the include DirectX SDK directory - for example, like this:

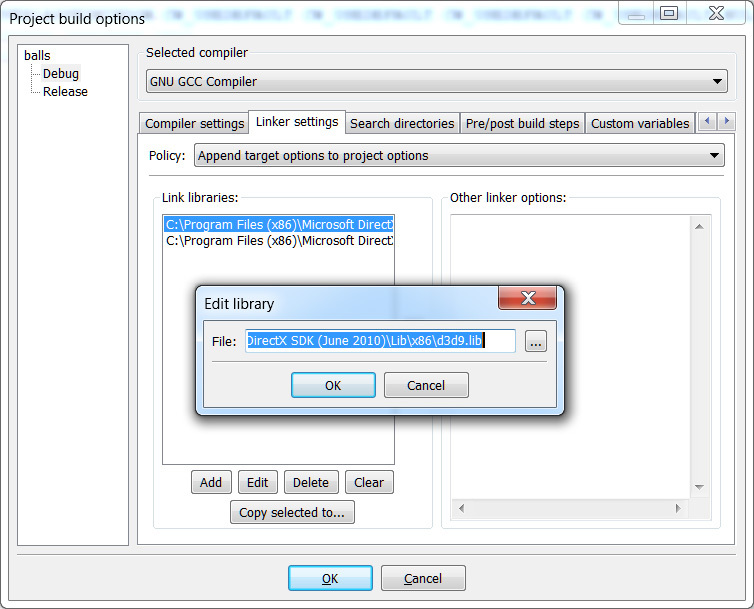

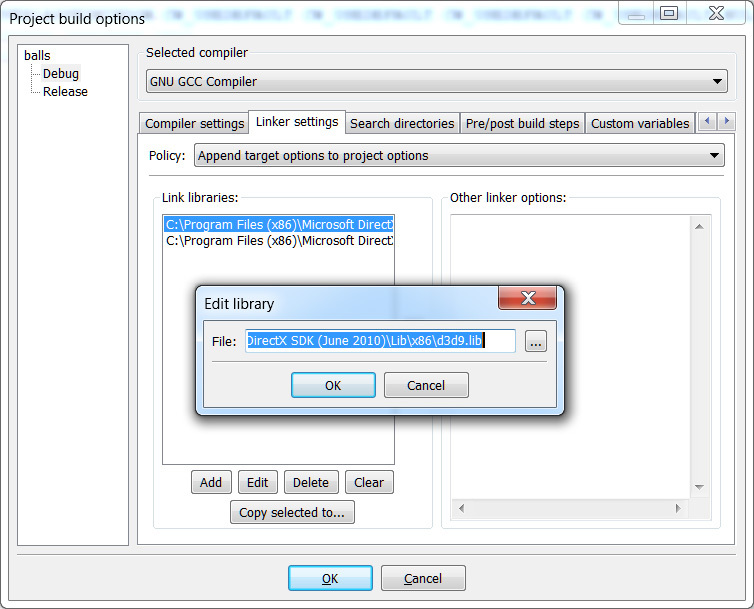

2) On the linker tab add two libraries - d3d9.lib and d3dx9.lib:

After that, in the source code of the application you will need to include Direct3D header files:

Here I made the first mistake: I started thinking about which design pattern to choose. He came to the conclusion that the MVC (model-view-controller) is best suited: the model will be the game class (game), including all the logic - calculating the paths of movement, the appearance of balls, analysis of explosive combinations; the presentation will be the engine class responsible for drawing and interaction with Direct3D; the controller will be the actual wrapper (app) - this includes the message processing cycle, processing user input, and, most importantly, the state manager and ensuring the interaction of game and engine objects. It seems to be simple, and you can start writing header files, but it was not there! At this stage, it turned out to be very difficult to navigate and understand what methods these classes should have. It is clear that this was a complete lack of experience, and I decided to resort to the advice of one of the books: “Do not try to write the perfect code from the very beginning, let it be non-optimal and confused. Understanding comes with time, and you can do refactoring later. ” As a result, after several iterations of the refactoring of an already working layout, the definition of the three main classes took the form:

The TGame class has only 3 methods that the user himself can initiate - New (new game), Select (ball selection) and TryMove (attempt to move the ball). The remaining auxiliary ones are called by the controller in special cases. For example, DetonateTest (test for explosive combinations) is called after the appearance of new balls or after an attempt to move. GetNewBallList, GetLastMovePath, GetDetonateList are called, respectively, after the balls appear, after moving and after the explosion, with one goal: to get a list of specific balls and pass it to the engine object for processing so that it can draw something. I don’t want to dwell on the logic of TGame, since there are source codes with comments . I can only say that the definition of the path of displacement of the ball is implemented using the Dijkstra algorithm using an undirected graph with equal weights of all edges.

Let us consider the classes of the engine and controller.

Consider the main Render method:

At the very beginning, it calculates how many milliseconds have passed since the previous Render () call, then the progress of the animations are updated if they are active. The buffers are cleared by the Clear method and the platform, the balls and the particle system are sequentially drawn if it is active. Finally, a line is displayed with the current value of points earned.

Here is a lightweight controller. A similar message loop can be found in any book on Direct3D:

Only what is inside the else block deserves attention - this is the so-called IdleFunction, which is executed in the absence of messages.

And here is the state manager function:

Well, perhaps that's all!

Here is the place to list the shortcomings. Of course, in the code a lot of places for optimizations. In addition, I did not mention such things as changing video mode parameters (screen resolution, multisampling) and device loss handling (LostDevice). On account of the latter there is a detailed discussion on the gamedev.ru site .

I hope my research will benefit someone. By the way, the source code on github .

Thanks for attention!

1. Frank D. Luna Introduction to programming 3D games with DirectX 9.0 - to understand the basics;

2. Gornakov S. DirectX9 programming lessons in C ++ are also the basics, but there are chapters on DirectInput, DirectSound and DirectMusic. In the examples of programs sometimes errors are found;

3. Flenov ME DirectX and C ++ the art of programming is an amusing style of presentation. Basically, the purpose of the book is to create animated videos using interesting effects, including shaders. Judge for yourself by the name of the sections: heart attack, fire dragon;

4. Barron Todd. Programming strategic games with DirectX 9 - fully devoted to the topics related to strategic games: block graphics, AI, creating maps and landscapes, sprites, special effects with particle systems, as well as developing screen interfaces and working with DirectSound / Music;

5. Bill Fleming 3D Creature WorkShop - a book not on programming, but on the development of three-dimensional character models in LightWave, 3D Studio Max, Animation Master;

6. Thorn Alan DirectX 9 User interfaces Design and implementation - a detailed book on the development of graphical interfaces with DirectX. A hierarchical model of screen form components, similar to that implemented in Delphi, is considered;

7. Adams Jim Advanced Animation with DirectX - discusses the types of animation (skeletal, morphing and varieties) and their implementation, as well as working with geometry and animation from X-files;

8. Lamot Andre Programming games for Windows. Tips from a professional - this book is already more serious: questions of optimization, selection of data structures for various tasks, multithreading, physical modeling, AI are being considered. The last chapter describes the creation of a game about a spacecraft and aliens;

9. David H. Eberly 3D Game Engine Design is a good book for understanding the whole theory of game development: first, graphics API technologies are described (transformation, rasterization, shadowing, blending, multitexturing, fog, etc.), then topics such as the scene graph , object selection, collision detection, character animation, level of detail, landscapes;

10. Daniel Sánchez-Crespo Dalmau - details the algorithms and data structures used in game-building tasks, such as AI, scripting, rendering in closed and in open spaces, clipping algorithms, procedural techniques, ways to implement shadows , the implementation of the camera, etc .;

11. Andre Lamoth Programming Role Playing Games with directX 9 - a thousand-page detailed RPG development guide. Includes both theoretical chapters on programming with Direct3D, DirectInput, DirectSound, DirectPlay, and application chapters that are directly related to the game engine.

Introduction

So, in my free time I decided to explore the popular graphic API. After reading a few books and examining a bunch of examples and tutorials (including from the DirectX SDK), I realized that the very moment had come when it was worth trying your own efforts. The main problem was that most of the existing examples simply demonstrate this or that API capability and are implemented procedurally in almost one cpp-file, and even using the DXUT wrapper, and do not give an idea of what structure the final application should have what classes need to be designed and how it should all interact with each other, so that everything is beautiful, readable and efficiently work. This disadvantage also applies to books on Direct3D: for example, for many newbies, it is not obvious that render states do not always need to be updated when every frame is drawn, and also that most heavy operations (such as filling the vertex buffer) should be performed just once when the application is initialized (or when the game level is loaded).

Idea

The first thing I needed was to decide on the very idea of the game. The old game from 1992 under MS-DOS came to mind, which I think is familiar to many. This is a logical game Lines of the company Gamos.

Well, the challenge is accepted. Here is what we have:

- there is a square box of cells;

- in the cells on the field there are multicolored balls;

- after moving the ball, new balls appear;

- the player’s goal is to build one-color balls in a line: the accumulation of a certain number of one-color balls in one line leads to their detonation and scoring;

- The main task is to hold out as long as possible, until the free cells on the field run out.

Now let's look from the point of view of the Direct3D application:

- we will make a field of cells in the form of a three-dimensional platform with protrusions, each cell will be something like a podium;

- Three types of ball animation should be implemented:

- the appearance of the ball: first a small ball appears, which in a short time grows to an adult size;

- movement of the ball: just a sequential movement in the cells;

- bouncing ball: when choosing a ball with the mouse, it should be activated and start jumping on the spot;

- A particle system must be implemented that will be used to animate the explosion;

- Text output must be implemented: to display points earned on the screen;

- Virtual camera control should be implemented: rotation and zoom.

In fact, the points listed above are a pathetic likeness of a document called a design project. I strongly recommend, before starting development, to paint it in every detail, print it out and keep it in front of your eyes! Looking ahead, I immediately show a demo video for clarity of the implementation of the points (by the way, the video was recorded using the ezvid program, so do not be intimidated by their splash screen in the beginning):

')

Start of development

So far I have not mentioned which tools were used. First, you need the DirectX software development kit (SDK), always available for free download on the Microsoft website: DirectX SDK . If you are going to use the version of Direct3D 9, like me, then after installation you need to open the DirectX Control Panel through the main menu and on the Direct3D 9 tab choose which version of libraries will be used during assembly - retail or debug (this affects whether Direct3D will report debugger on the results of its activities):

Debug or retail

Why Direct3D version 9? Because this is the latest version, where there is still a fixed function pipeline, that is, a fixed graphics pipeline, which includes, for example, the functions of lighting calculation, vertex processing, mixing, and so on. Starting from the 10th version, developers are invited to independently implement these functions in shaders, which is an indisputable advantage, but, in my opinion, it is difficult to understand at the first experiments with Direct3D.

Why Code :: blocks? It was probably silly to use a cross-platform IDE to develop an application using a non-cross-platform API. Just Code :: blocks takes up several times less space than Visual Studio, which turned out to be very relevant for my country PC.

Starting development with Direct3D was very simple. I created an empty project in Code :: blocks, then I had to do two things in the build options:

1) On the search directories tab and the compiler subtab, add the path to the include DirectX SDK directory - for example, like this:

Search directories

2) On the linker tab add two libraries - d3d9.lib and d3dx9.lib:

Linker

After that, in the source code of the application you will need to include Direct3D header files:

#include "d3d9.h" #include "d3dx9.h" Application structure

Here I made the first mistake: I started thinking about which design pattern to choose. He came to the conclusion that the MVC (model-view-controller) is best suited: the model will be the game class (game), including all the logic - calculating the paths of movement, the appearance of balls, analysis of explosive combinations; the presentation will be the engine class responsible for drawing and interaction with Direct3D; the controller will be the actual wrapper (app) - this includes the message processing cycle, processing user input, and, most importantly, the state manager and ensuring the interaction of game and engine objects. It seems to be simple, and you can start writing header files, but it was not there! At this stage, it turned out to be very difficult to navigate and understand what methods these classes should have. It is clear that this was a complete lack of experience, and I decided to resort to the advice of one of the books: “Do not try to write the perfect code from the very beginning, let it be non-optimal and confused. Understanding comes with time, and you can do refactoring later. ” As a result, after several iterations of the refactoring of an already working layout, the definition of the three main classes took the form:

Class tgame

class TGame { private: BOOL gameOver; TCell *cells; WORD *path; WORD pathLen; LONG score; void ClearField(); WORD GetSelected(); WORD GetNeighbours(WORD cellId, WORD *pNeighbours); BOOL CheckPipeDetonate(WORD *pPipeCells); public: TGame(); ~TGame(); void New(); BOOL CreateBalls(WORD count); void Select(WORD cellId); BOOL TryMove(WORD targetCellId); BOOL DetonateTest(); WORD GetNewBallList(TBallInfo **ppNewList); WORD GetLastMovePath(WORD **ppMovePath); WORD GetDetonateList(WORD **ppDetonateList); LONG GetScore(); BOOL IsGameOver(); }; TEngine class

class TEngine { private: HWND hWindow; RECT WinRect; D3DXVECTOR3 CameraPos; LPDIRECT3D9 pD3d; LPDIRECT3DDEVICE9 pDevice; LPDIRECT3DTEXTURE9 pTex; LPD3DXFONT pFont; D3DPRESENT_PARAMETERS settings; clock_t currentTime; TGeometry *cellGeometry; TGeometry *ballGeometry; TParticleSystem *psystem; TBall *balls; TAnimate *jumpAnimation; TAnimate *moveAnimation; TAnimate *appearAnimation; LONG score; void InitD3d(); void InitGeometry(); void InitAnimation(); void DrawPlatform(); void DrawBalls(); void UpdateView(); public: TEngine(HWND hWindow); ~TEngine(); void AppearBalls(TBallInfo *ballInfo, WORD count); void MoveBall(WORD *path, WORD pathLen); void DetonateBalls(WORD *detonateList, WORD count); BOOL IsSelected(); BOOL IsMoving(); BOOL IsAppearing(); BOOL IsDetonating(); void OnResetGame(); WORD OnClick(WORD x, WORD y, BOOL *IsCell); void OnRotateY(INT offset); void OnRotateX(INT offset); void OnZoom(INT zoom); void OnResize(); void OnUpdateScore(LONG score); void Render(); }; TApplication class

class TApplication { private: HINSTANCE hInstance; HWND hWindow; POINT mouseCoords; TEngine* engine; TGame* game; BOOL moveStarted; BOOL detonateStarted; BOOL appearStarted; void RegWindow(); static LRESULT CALLBACK MsgProc(HWND hwnd, UINT msg, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam); void ProcessGame(); public: TApplication(HINSTANCE hInstance, INT cmdShow); ~TApplication(); TEngine* GetEngine(); TGame* GetGame(); INT MainLoop(); }; The TGame class has only 3 methods that the user himself can initiate - New (new game), Select (ball selection) and TryMove (attempt to move the ball). The remaining auxiliary ones are called by the controller in special cases. For example, DetonateTest (test for explosive combinations) is called after the appearance of new balls or after an attempt to move. GetNewBallList, GetLastMovePath, GetDetonateList are called, respectively, after the balls appear, after moving and after the explosion, with one goal: to get a list of specific balls and pass it to the engine object for processing so that it can draw something. I don’t want to dwell on the logic of TGame, since there are source codes with comments . I can only say that the definition of the path of displacement of the ball is implemented using the Dijkstra algorithm using an undirected graph with equal weights of all edges.

Let us consider the classes of the engine and controller.

TEngine

- The class defines fields for storing the handle of the window and its rectangle. They are used in the OnResize method, which the controller calls when the window is resized, to calculate the new projection matrix.

- The CameraPos field stores the coordinates of the observer in world space. The vector of the direction of sight is not necessary to store, because according to my idea the camera is always directed to the origin of coordinates, which, by the way, coincides with the center of the platform.

- There are also pointers to Direct3D interfaces: LPDIRECT3D9, which is needed only to create a device; LPDIRECT3DDEVICE9 - in fact, the Direct3D device itself, the main interface with which to work; LPD3DXFONT and LPDIRECT3DTEXTURE9 for working with text and texture.

- The currentTime field is used to store the current time in milliseconds and is required to draw a smooth animation. The fact is that each frame takes a different number of milliseconds, so you have to measure these milliseconds each time and use it as a parameter when interpolating the animation. This method is known as time synchronization and is used everywhere in modern graphic applications.

- Pointers to objects of the TGeometry class (cellGeometry and ballGeometry) store the geometry of a single cell and one ball. The TGeometry object itself, as the name implies, is designed to work with geometry and contains vertex and index buffers, as well as a description of the material (D3DMATERIAL9). When drawing, we can change the world matrix and call the Render method of the TGeometry object, which will lead to drawing several cells or balls.

- TParticleSystem is a class of a particle system that has methods for initializing a set of particles, updating their positions in space and, of course, rendering.

- TBall * balls - an array of balls with color and status information [bouncing, moving, appearing].

- Three objects of type TAnimate - to provide animation. The class has a method for initializing keyframes, which are world transformation matrixes, and methods for calculating the current animation position and applying the transformation. In the rendering procedure, the engine object sequentially draws the balls and, if necessary, calls the ApplyTransform method of the desired animation in order to create or move the ball.

- InitD3d, InitGeometry, InitAnimation are called only from the TEngine constructor and are separated into separate methods for clarity. In InitD3d, a Direct3D device is created and all necessary render states are installed, including the installation of a point light source with a specular component right above the center of the platform.

- The three methods AppearBalls, MoveBall and DetonateBalls trigger the appearance, move and explosion animations, respectively.

- The methods IsSelected, IsMoving, IsAppearing, IsDetonating are used in the state manager function to track the end of the animation.

- Methods with the prefix On are called by the controller when the corresponding events occur: mouse click, camera rotation, etc.

Consider the main Render method:

TEngine :: Render ()

void TEngine::Render() { //, clock_t elapsed=clock(), deltaTime=elapsed-currentTime; currentTime=elapsed; // , if(jumpAnimation->IsActive()) { jumpAnimation->UpdatePosition(deltaTime); } if(appearAnimation->IsActive()) { appearAnimation->UpdatePosition(deltaTime); } if(moveAnimation->IsActive()) { moveAnimation->UpdatePosition(deltaTime); } pDevice->Clear(0,NULL,D3DCLEAR_STENCIL|D3DCLEAR_TARGET|D3DCLEAR_ZBUFFER,D3DCOLOR_XRGB(0,0,0),1.0f,0); pDevice->BeginScene(); // DrawPlatform(); // DrawBalls(); // , if(psystem->IsActive()) { pDevice->SetTexture(0,pTex); psystem->Update(deltaTime); psystem->Render(); pDevice->SetTexture(0,0); } // char buf[255]="Score: ",tmp[255]; itoa(score,tmp,10); strcat(buf,tmp); RECT fontRect; fontRect.left=0; fontRect.right=GetSystemMetrics(SM_CXSCREEN); fontRect.top=0; fontRect.bottom=40; pFont->DrawText(NULL,_T(buf),-1,&fontRect,DT_CENTER,D3DCOLOR_XRGB(0,255,255)); pDevice->EndScene(); pDevice->Present(NULL,NULL,NULL,NULL); } At the very beginning, it calculates how many milliseconds have passed since the previous Render () call, then the progress of the animations are updated if they are active. The buffers are cleared by the Clear method and the platform, the balls and the particle system are sequentially drawn if it is active. Finally, a line is displayed with the current value of points earned.

TApplication

- The class has a field for storing mouse coordinates, since we will need to calculate the values of relative cursor offsets in order to rotate the camera.

- The Boolean flags appearStarted, moveStarted, and detonateStarted are needed to track the status of the corresponding animations.

- The RegWindow method renders the code for registering the window class.

- The MsgProc static method is the so-called window procedure.

- ProcessGame is a simplified version of the state manager, in which the current state of the game is evaluated and, depending on it, some actions are taken.

- MainLoop - message loop.

Here is a lightweight controller. A similar message loop can be found in any book on Direct3D:

TApplication :: MainLoop ()

INT TApplication::MainLoop() { MSG msg; ZeroMemory(&msg,sizeof(MSG)); while(msg.message!=WM_QUIT) { if(PeekMessage(&msg,NULL,0,0,PM_REMOVE)) { TranslateMessage(&msg); DispatchMessage(&msg); } else { // , ProcessGame(); engine->Render(); } } return (INT)msg.wParam; } Only what is inside the else block deserves attention - this is the so-called IdleFunction, which is executed in the absence of messages.

And here is the state manager function:

TApplication :: ProcessGame ()

void TApplication::ProcessGame() { if(moveStarted) { // if(!engine->IsMoving()) { // - moveStarted=FALSE; if(game->DetonateTest()) { // WORD *detonateList, count=game->GetDetonateList(&detonateList); detonateStarted=TRUE; engine->DetonateBalls(detonateList,count); engine->OnUpdateScore(game->GetScore()); } else { // if(game->CreateBalls(APPEAR_COUNT)) { TBallInfo *appearList; WORD count=game->GetNewBallList(&appearList); appearStarted=TRUE; engine->AppearBalls(appearList,count); } else { //game over! } } } } if(appearStarted) { // if(!engine->IsAppearing()) { appearStarted=FALSE; // - if(game->DetonateTest()) { // WORD *detonateList, count=game->GetDetonateList(&detonateList); detonateStarted=TRUE; engine->DetonateBalls(detonateList,count); engine->OnUpdateScore(game->GetScore()); } } } if(detonateStarted) { // if(!engine->IsDetonating()) { // detonateStarted=FALSE; } } } Well, perhaps that's all!

Conclusion

Here is the place to list the shortcomings. Of course, in the code a lot of places for optimizations. In addition, I did not mention such things as changing video mode parameters (screen resolution, multisampling) and device loss handling (LostDevice). On account of the latter there is a detailed discussion on the gamedev.ru site .

I hope my research will benefit someone. By the way, the source code on github .

Thanks for attention!

Promised literature

1. Frank D. Luna Introduction to programming 3D games with DirectX 9.0 - to understand the basics;

2. Gornakov S. DirectX9 programming lessons in C ++ are also the basics, but there are chapters on DirectInput, DirectSound and DirectMusic. In the examples of programs sometimes errors are found;

3. Flenov ME DirectX and C ++ the art of programming is an amusing style of presentation. Basically, the purpose of the book is to create animated videos using interesting effects, including shaders. Judge for yourself by the name of the sections: heart attack, fire dragon;

4. Barron Todd. Programming strategic games with DirectX 9 - fully devoted to the topics related to strategic games: block graphics, AI, creating maps and landscapes, sprites, special effects with particle systems, as well as developing screen interfaces and working with DirectSound / Music;

5. Bill Fleming 3D Creature WorkShop - a book not on programming, but on the development of three-dimensional character models in LightWave, 3D Studio Max, Animation Master;

6. Thorn Alan DirectX 9 User interfaces Design and implementation - a detailed book on the development of graphical interfaces with DirectX. A hierarchical model of screen form components, similar to that implemented in Delphi, is considered;

7. Adams Jim Advanced Animation with DirectX - discusses the types of animation (skeletal, morphing and varieties) and their implementation, as well as working with geometry and animation from X-files;

8. Lamot Andre Programming games for Windows. Tips from a professional - this book is already more serious: questions of optimization, selection of data structures for various tasks, multithreading, physical modeling, AI are being considered. The last chapter describes the creation of a game about a spacecraft and aliens;

9. David H. Eberly 3D Game Engine Design is a good book for understanding the whole theory of game development: first, graphics API technologies are described (transformation, rasterization, shadowing, blending, multitexturing, fog, etc.), then topics such as the scene graph , object selection, collision detection, character animation, level of detail, landscapes;

10. Daniel Sánchez-Crespo Dalmau - details the algorithms and data structures used in game-building tasks, such as AI, scripting, rendering in closed and in open spaces, clipping algorithms, procedural techniques, ways to implement shadows , the implementation of the camera, etc .;

11. Andre Lamoth Programming Role Playing Games with directX 9 - a thousand-page detailed RPG development guide. Includes both theoretical chapters on programming with Direct3D, DirectInput, DirectSound, DirectPlay, and application chapters that are directly related to the game engine.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/251081/

All Articles