IT-company management: separating theory from practice

Practice is when everything works, but no one understands how. Theory is when nothing works, but everyone knows exactly why. We came to a combination of theory and practice: nothing works - and no one understands why.

In the operation of any growing business - not only in IT, but also in other areas - there comes a time when it becomes impossible to ignore the problems thrown into the far corner and having already covered the noble patina of the problem. Their consequences make themselves felt in unexpected situations. There are more than a dozen methods to deal with the problems and get the business to work, but you always have to start from the same thing: analyzing the root causes of these very problems. And today, the Robots would like to talk about it - not only by translating an article about the search for the root causes of IT business coach and Agile, Scrum and Kanban specialist Henrik Kniberg - but also talking about how Robots fixed some of their own breakdowns.

')

Henrik Kniberg. Purpose of the article

Cause-effect diagrams (cause-effect diagrams) are a simple and convenient way to perform root cause analysis. I have been using these diagrams for many years, helping a business recognize and solve a wide range of problems, both technical and organizational. The purpose of the article is to show how cause-effect diagrams work and to teach the reader to build them for their own needs.

Troubleshoot problems, not symptoms

The key to effective problem solving is first and foremost to make sure that you understand the problem you are trying to solve. Why it requires a solution, how to determine when it will be solved, and what is the root cause of this problem.

Often the “symptoms” appear in one place, although the true cause of the problem is quite different. If you just deal with the elimination of symptoms, not trying to assess the situation more deeply, it is likely that the problem will let you know again later - but in a different form.

Problem: Smoke in the bedroom.

Bad decision: Open the window and go to bed again.

Good solution: Find the source of the smoke and deal with it. Oops! And in the basement of a fire! Further actions - put out the fire; understand why it came about; set a fire alarm to learn about the problem the next time before.

Problem: Hot forehead, fatigue.

Bad decision: Apply ice to the forehead to cool it. Eat sugar for energy. Continue work.

A good solution: To measure the temperature. Yes, I have a fever! Further actions - go home to rest.

Problem: Server memory leak.

Bad decision: Buy more memory.

A good solution: Find and fix a source of memory leak. Conduct testing to avoid future leaks.

... and further in the same vein.

Most of the problems in organizations is systemic. The system (business) fails, and the failure must be eliminated. While the root cause of this failure is not clear, most attempts to deal with the problem will be ineffective or even counterproductive.

A3 thinking and a lean approach to problem solving

One of the fundamental principles of lean thinking is Kaizen - continuous improvement of processes. In one of the most successful companies in the world, Toyota, they associate a significant share of success with their high discipline in terms of approach to solving problems. Sometimes this approach is called “thinking in A3 format” (knowledge gained during each “problem solving session” is recorded on sheets A3).

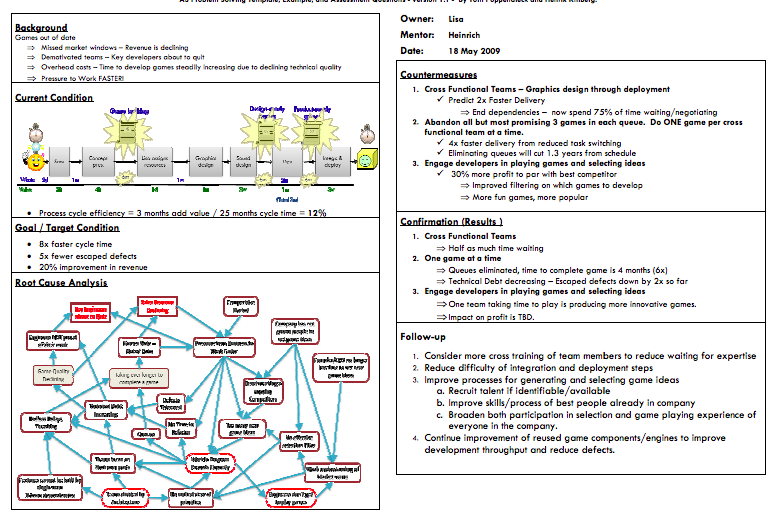

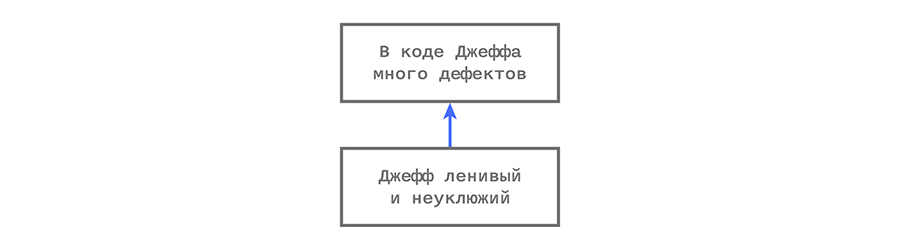

Here is an example and template:

www.crisp.se/gratis-material-och-guider/a3-template

With the “A3-approach”, a significant part of the time (left side of the sheet) is devoted to the analysis and visualization of the analysis of the root cause of the problem and precedes the development of any solutions . Causal charts are not the only method for analyzing root causes. There are also others: for example, the systematization of the value stream (value stream mapping) and the construction of the Ishikawa diagram, or, as it is also called, the “fishbone” diagram. Sample A3 above contains a value stream map (top left) and a causal diagram (bottom left).

Causal diagrams are good for their intuitiveness and no need for additional explanations (especially in comparison with the charts of “fish bone”). Another advantage is the ability to illustrate repetitive vicious cycles , which is extremely useful from the point of view of system thinking. Next, we will discuss how to effectively create and use such diagrams.

How to use cause-effect diagrams

The basic process is as follows:

The next stage is follow up. If the countermeasures worked, congratulations! If not - do not despair. Analyze why they did not work, update the diagram, taking into account the knowledge gained, and try other countermeasures.

In fact, countermeasures are not a solution, but an experiment . Your hypothesis is that countermeasures will solve (or minimize) the problem, but you can never be completely sure. In fact, you “poke a sharp stick” into your system, checking how it reacts. Therefore, follow up is important.

The error, in fact, means that your system sends you signals that you should listen to. The only real mistake is the inability to learn from mistakes!

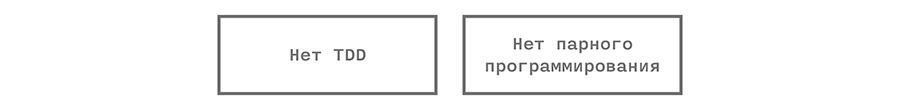

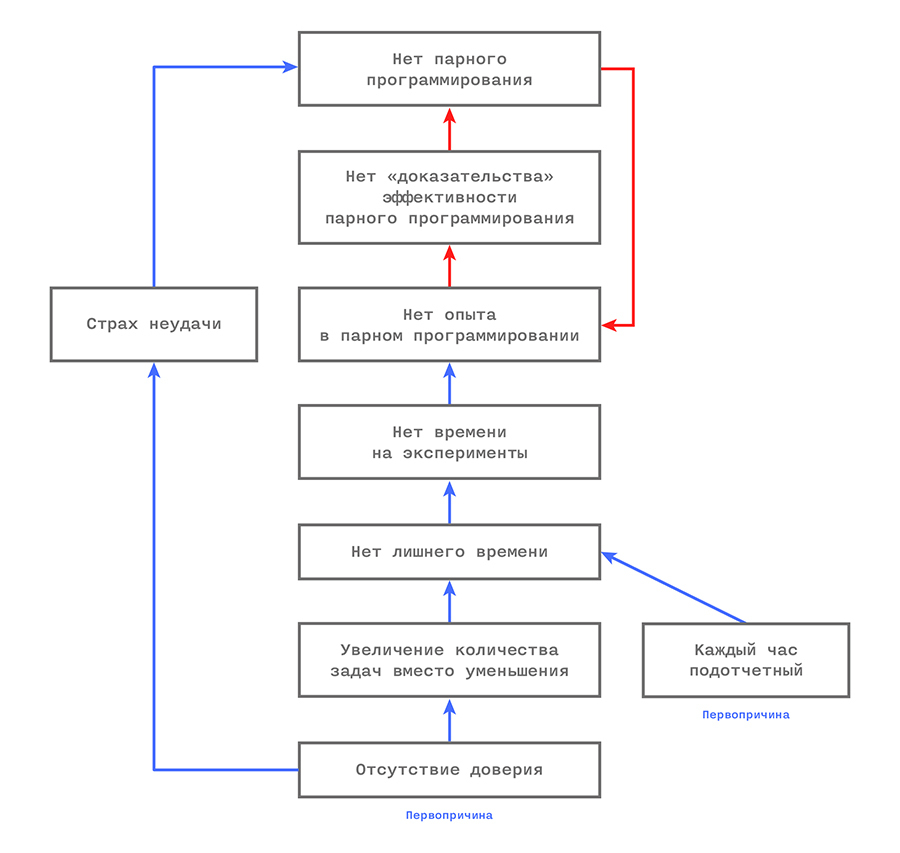

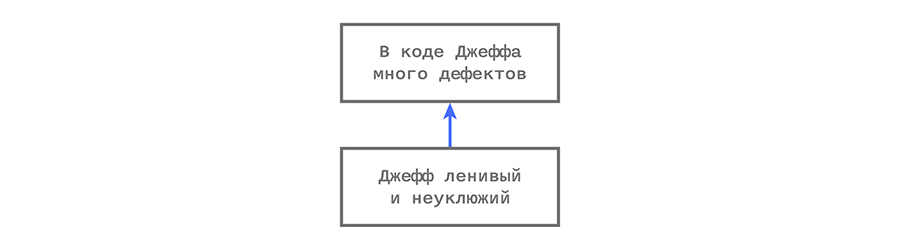

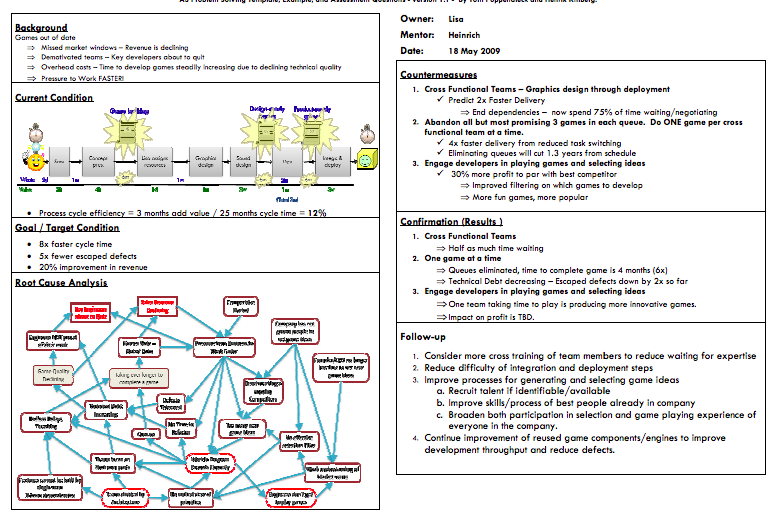

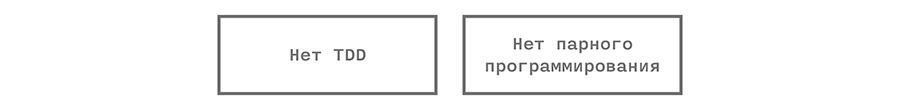

Example 1: Lack of pair programming

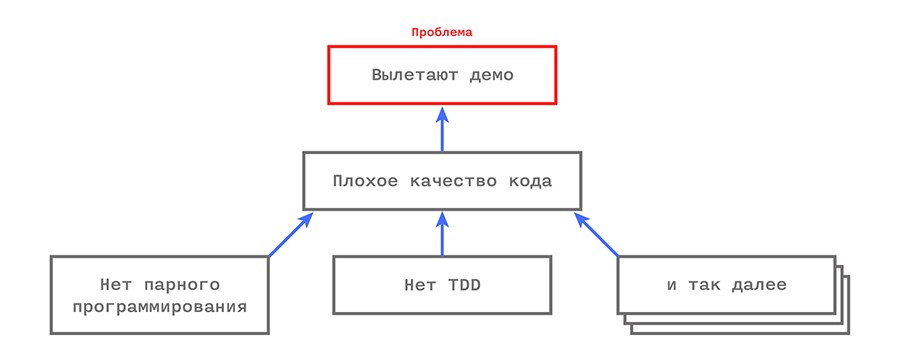

One client asked to help him figure out why his business does not use XP techniques like pair programming and test-driven development (TDD). “We know we should do it, but we don’t,” said the client.

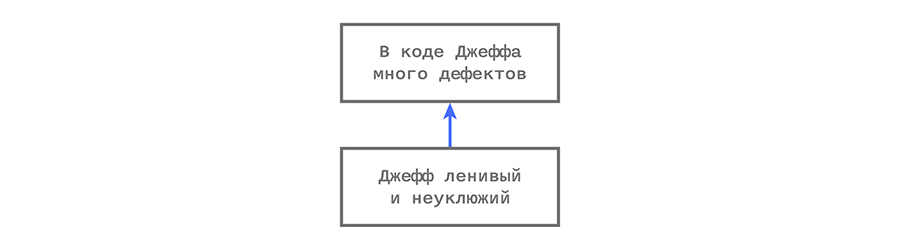

Is the lack of TDD and pair programming a real problem? As usual, often the things we call problems are not, but are just symptoms.

Q: What are the consequences of ignoring pair programming and TDD?

A: We believe that using these practices would improve the quality of the code.

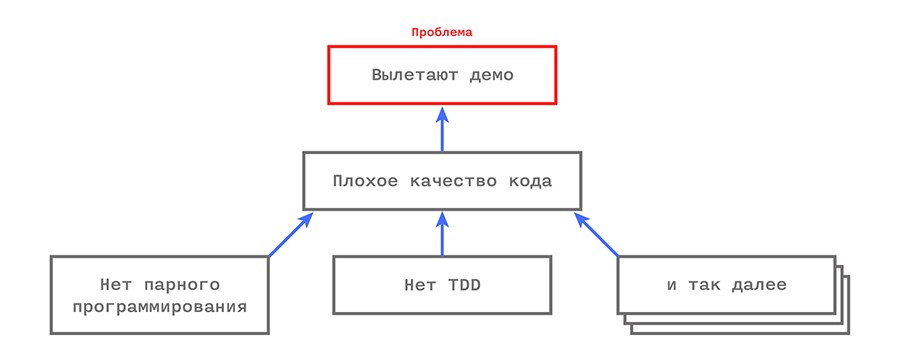

Q: What are the consequences of poor code quality? Have you encountered real problems caused by poor code quality?

A: Yes, we got demos. Demo is a key element of our business, so this is a real problem.

OK, let's look at one of the elements and see if we can build a link to the very "basics".

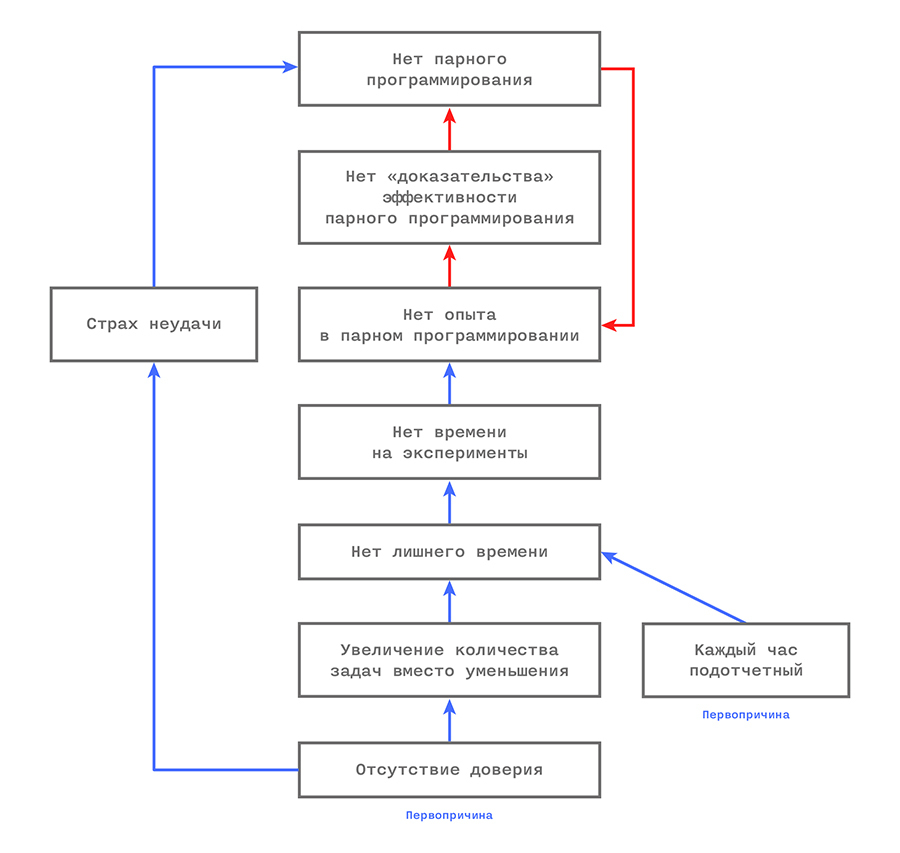

Q: Why don't you practice pair programming?

A: Because many fear that it will not work and we will waste time. We have no proof that it works.

Q: What evidence do you need?

A: Well, we have seen studies that show that it is effective. But in our company, no one in fact tried to introduce such practices, so we are not sure of success.

Here is the first loop:

They do not want to introduce new practices, because they are not sure whether they will work. And they do not know if they are working, because they have not tried to implement them ...

Q: Why did you at least make no attempt to use pair programming as an experiment?

A: We have no time to experiment.

Q: Why?

A: Because we do not have a temporary reserve. Every hour accountable. And customers continue to overwhelm us with work.

Q: Why customers do not give you the opportunity to manage their time and consider it possible to pile on you work at any convenient time?

A: They do not trust us to independently allocate time.

The lack of trust also leads to the fear of failure in general, which, of course, reduces the likelihood of experimenting with new techniques like pair programming without guarantees that they will work.

It turns out that there are two global root causes: the lack of trust and the management setup for accounting each hour. Now back to the big picture.

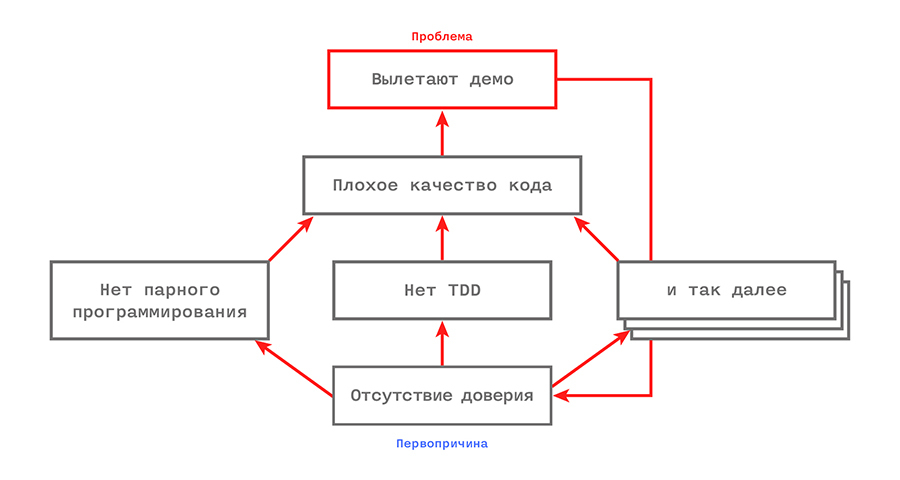

The lack of trust between the client and the customer turned out to be the root cause of the fact that XP practices, such as TDD and pair programming, are not being introduced. This entails a bad quality, due to which the demos are crashed. And you would never guess: departing demo will reduce mutual trust even more. This is a vicious circle!

Interestingly, we performed this analysis during a two-day workshop with approximately 25 people. At the beginning, we mainly talked about technical things - how to get started with TDD and pair programming. This approach was not particularly effective; instead, we divided into groups and decided that each group chooses its own problem and begins to build a cause-effect diagram and formulate a solution to the problem on sheets A3. Interestingly, several groups, which analyzed at first glance different problems, eventually came to the same root cause: lack of trust. The diagram above is just one of the examples that illustrate this.

Thus, by the end of the master class, the conversation was about how to increase the degree of trust between the client and the developer. It was an unexpected turn of the workshop. For a start, we agreed that next time we will invite “them” (clients) to the workshop, which should reduce the frequency of the opposition “we” and “they”.

Example 2: long release cycle

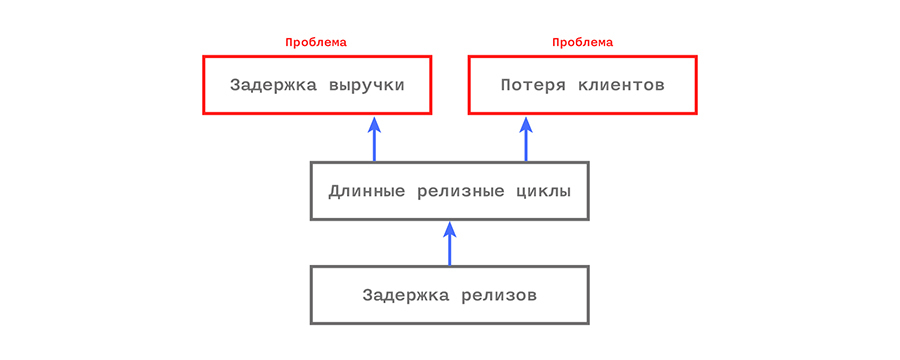

Suppose we have a problem: we always break deadlines. More precisely, our releases always come out later than the scheduled time.

The problem is only a problem if it prevents you from achieving the goal. Therefore, the first step is to determine the goal and think about the consequences of the problem directly in the context of your goal. This will help the question “So what?”, Which must be asked until you can identify the obvious damage.

Suppose that the goal is to make customers happy and get maximum revenue. The dialogue may look something like this:

Q: “What is the negative effect of postponing releases? What could be the consequences? ”

A: “Delays make our release cycles long”

Q: “So what?”

A: “This postpones the receipt of revenue and negatively affects the speed of money in the company. We also lose customers because of their impatience. ”

In the process of dialogue, we add cells and cause-and-effect arrows to the diagram. Usually I try to move “ascending” from the originally stated problem, “mapping” its consequences. But this is not a strict rule.

That is, it turns out that the delay in releases is actually not a problem. True problems are revenue lag and loss of customers. At this stage it is necessary to consider three points:

Are there any other factors leading to loss of customers and revenue lag? If so, can we assume that all the delay in releases is to blame, or should we turn our attention to something else? Is it possible to quantify the problem? How much money have we lost? How many customers left? These data will help us estimate the amount of effort that justifies itself in solving the identified problem.

How do we understand what solved the problem? Suppose a happy consultant bursts into the office and proudly declares: “I solved the problem!”. How to determine that this is not a bluff?

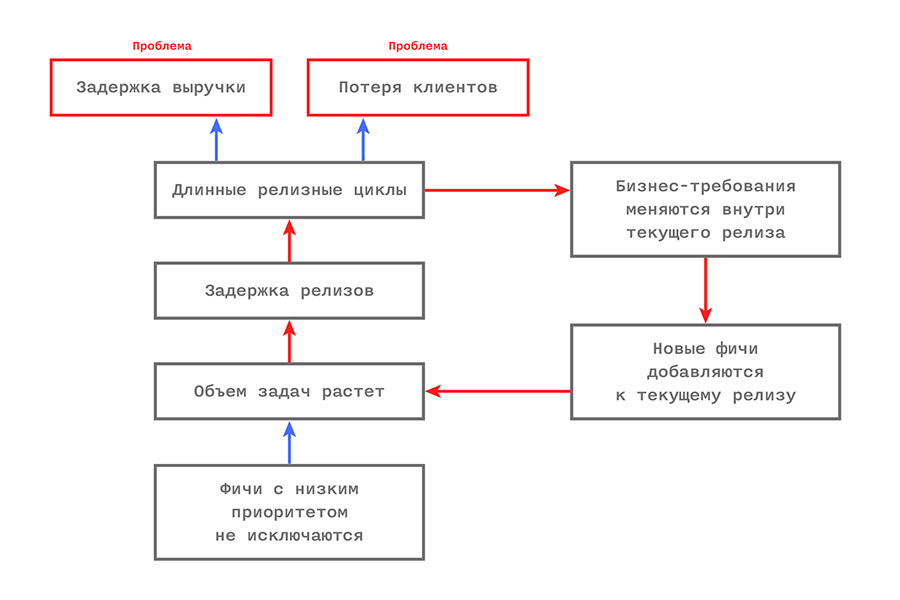

After analyzing the consequences of the problem, it is time to dig deep into the root cause.

And here come the questions “Why”. Yes, there is a “five why” technique that you could hear about if you studied lean thinking.

Q: “Why are releases delayed?”

A: “Because the amount of work is growing.”

Q: “Why?”

A: “Because customers invent more and more new features and insist that they need to be added to the current release, refusing to exclude low priority features from it.”

Q: “Why? Why not postpone adding new features to new releases? ”

A: “Because the release cycle is so long that new requirements arise before the next release”

There are only three "Why." But you understood the principle. The dialogue allows you to form the following picture:

The vicious cycle is marked by red arrows. Repetitive problems almost always involve such “loops”, but it takes some time to identify them. If you have found such a loop, then the chances for a successful and irreversible solution to problems are many times greater!

Our goal is to identify the root cause of this problem so that we can achieve the maximum effect with minimal effort. At the first stage, you can easily overlook important reasons, so let's go back and ask some more questions.

Q: “Why is the release cycle long? Delayed releases - the only reason? ”

A: “Well, in fact, even without delay, our planned release cycles are quite long.”

Q: “How long is your planned release cycle?”

A: “Once a quarter.”

Q. “But why is it so long?”

A: “Because releases are expensive and complicated.”

Q: “Why?”

A: “Because in every release there are a lot of details and also because it’s manual work.”

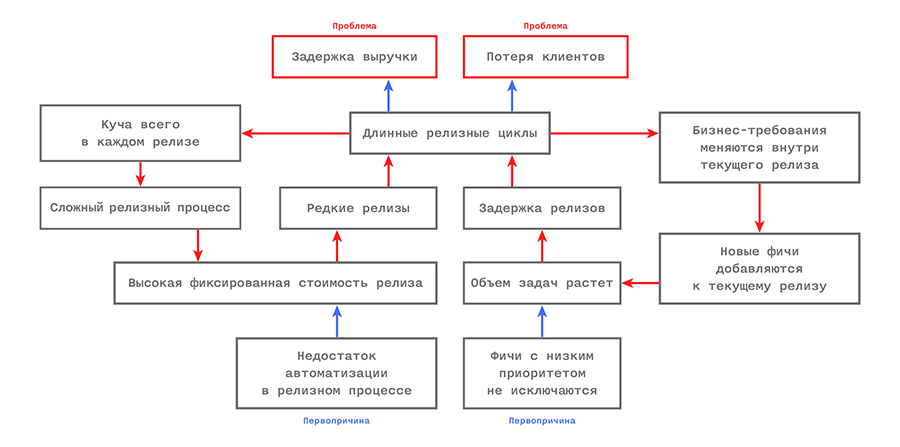

On the left we see another vicious cycle (red arrows)! The long interval between releases means that each new version includes a large number of updates, which makes product release a complex and expensive process. Because of this, we don’t want to make releases often.

As you noticed, here I decided to note two primary causes. And now - countermeasures:

Root cause

Lack of automation in the release preparation process

Countermeasure

Automate the release process

Root cause

Low-priority features are not excluded from releases.

Countermeasure

Agree with the client that new features can be added to the release only if the same number of low-priority features is excluded from it.

There is no strict rule telling which reason is the root cause, but there are some signs:

The “five why” technique is called so because usually there are about five questions that separate us from the original cause. There is a tendency to stop prematurely. Do not do this: keep digging!

It is necessary to take into account that the problem that was initially posed - delayed releases - in fact turned out to be neither a problem nor the root cause. It was just a symptom. We used it as a pretext to build a causal relationship upward to identify the true problem, and then downward to determine the root cause. This allows you to develop effective countermeasures with all your knowledge.

Without analysis of this type there is a risk to come to hasty conclusions and to make ineffective and counterproductive changes. For example, hiring additional employees, although the essence of the problem lies not in the amount of labor. Or by changing the reward system (encouraging people to do deadlines and penalizing late submission), although the existing reward system had nothing to do with the problem.

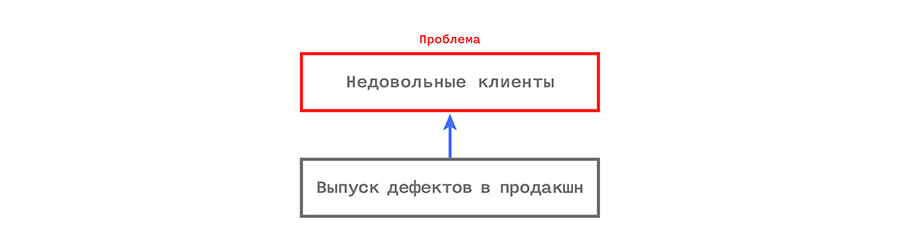

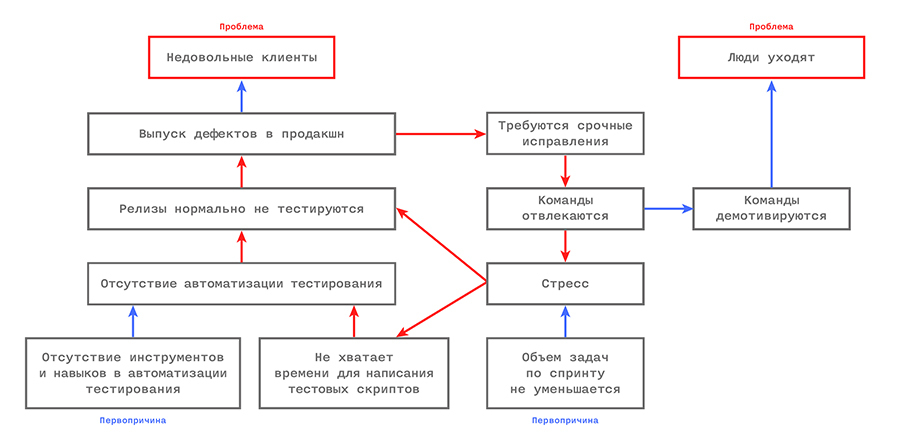

Example 3: defects in the production cycle

Imagine that we have problems with a defective code that runs in production.

Q: So what?

A: Defects anger our customers

Q: Why are defects run in production?

A: Because they did not pass the required testing prior to release.

Q: Why was there no testing?

Etc.

And that's what we get:

Two vicious cycles! Look at the red arrows.

Loop 1 (inner loop): Defects in the product force to make urgent changes, which distracts the team from work. Since employees are not exempt from the bulk of the tasks, they are under stress and do not have the time to properly test new releases. Which, of course, leads to an even greater number of defects at the level of the entire production.

Loop 2 (outer loop): Since employees are under stress, they also do not have time to write automatic test scripts. The consequence is a general lack of automation in testing, which increasingly complicates the regression testing of new releases. This, of course, leads to defects in production and the need to make urgent changes. And as a result - to even more stress.

But that's not all!

Teams hate it when they get distracted. The work process disrupts and ultimately kills motivation. This can be an explanation for the high turnover rates! Thus, by solving the underlying problem (defects in production), we get an additional bonus in the form of reducing staff turnover.

This is another advantage of causal analysis. Usually the root cause is the cause of more than one problem (which is why it is called “root” - primary or root).

Causal Analysis: Robots Experience

Boris Ryabchikov, Project Manager:

Example 4: A whole bunch of problems

And here is a larger example. The organization used the Scrum methodology, but faced some problems. As a result of several interviews and workshops, a causal diagram was born, which showed that Scrum was actually used incorrectly in the team, which caused problems.

It became obvious to everyone that many of the root causes could be eliminated by the correct use of Scrum (for example, reorganization into cross-functional teams, confidence that there is a product owner in every team). This was the impetus for organizational change, which eventually eliminated many of the root causes (green stars). The next step was to improve test automation.

Of course, Scrum is not a panacea. In fact, sometimes Scrum itself is a problem and then other techniques are required for the solution, for example, Kanban .

Practical questions - how to create and maintain charts

Work alone

When I make diagrams one, the most convenient tools are Visio or Powerpoint. They allow you to quickly move elements, resize cells, and quickly make a backup while working on an image.

Work in small groups (2 - 8 people)

Gather near the board or flipchart. Instead of cells, use stickers, connecting them with hand-drawn arrows. The board is preferable, since you can erase and redraw the arrows on it as you move the stickers. Let all members of the group participate, not just one person. It is important not to forget to take a clear photo of what happened, and send it to all participants after the meeting.

Work in larger groups (9 - 30 people)

Let group members break up into small teams, each focusing on a specific problem. Working with several teams on the same problem is useful: you can come to the same or different conclusions, and both results will be interesting. Each team works with a separate flipchart / board and stickers. Periodically, teams should meet for short joint discussions and share experiences.

Work with a diagram in perspective

Let the diagram remain in the program you used: Visio or Powerpoint. If you decide to return to it again in the workshop, determine its purpose: to show the diagram or update it. If this is an update, repeat it on the board / flipchart with stickers and arrows, so that the workshop participants can work together effectively on the diagram. After the meeting, “synchronize” the results with electronic tools.

This type of synchronization takes some time, but often it is worth it. For collaboration, nothing surpasses real tools: a board and stickers.

Danger

Too many arrows and cells

It happens that a diagram becomes so chaotic that it cannot be disassembled. Then it should be simplified. Here are some techniques:

Simplicity

- — . . , . , “ ” . : “” , .

:

, , . , . , : , , , , , . : .

In the operation of any growing business - not only in IT, but also in other areas - there comes a time when it becomes impossible to ignore the problems thrown into the far corner and having already covered the noble patina of the problem. Their consequences make themselves felt in unexpected situations. There are more than a dozen methods to deal with the problems and get the business to work, but you always have to start from the same thing: analyzing the root causes of these very problems. And today, the Robots would like to talk about it - not only by translating an article about the search for the root causes of IT business coach and Agile, Scrum and Kanban specialist Henrik Kniberg - but also talking about how Robots fixed some of their own breakdowns.

')

Henrik Kniberg. Purpose of the article

Cause-effect diagrams (cause-effect diagrams) are a simple and convenient way to perform root cause analysis. I have been using these diagrams for many years, helping a business recognize and solve a wide range of problems, both technical and organizational. The purpose of the article is to show how cause-effect diagrams work and to teach the reader to build them for their own needs.

Troubleshoot problems, not symptoms

The key to effective problem solving is first and foremost to make sure that you understand the problem you are trying to solve. Why it requires a solution, how to determine when it will be solved, and what is the root cause of this problem.

Often the “symptoms” appear in one place, although the true cause of the problem is quite different. If you just deal with the elimination of symptoms, not trying to assess the situation more deeply, it is likely that the problem will let you know again later - but in a different form.

Problem: Smoke in the bedroom.

Bad decision: Open the window and go to bed again.

Good solution: Find the source of the smoke and deal with it. Oops! And in the basement of a fire! Further actions - put out the fire; understand why it came about; set a fire alarm to learn about the problem the next time before.

Problem: Hot forehead, fatigue.

Bad decision: Apply ice to the forehead to cool it. Eat sugar for energy. Continue work.

A good solution: To measure the temperature. Yes, I have a fever! Further actions - go home to rest.

Problem: Server memory leak.

Bad decision: Buy more memory.

A good solution: Find and fix a source of memory leak. Conduct testing to avoid future leaks.

... and further in the same vein.

Most of the problems in organizations is systemic. The system (business) fails, and the failure must be eliminated. While the root cause of this failure is not clear, most attempts to deal with the problem will be ineffective or even counterproductive.

A3 thinking and a lean approach to problem solving

One of the fundamental principles of lean thinking is Kaizen - continuous improvement of processes. In one of the most successful companies in the world, Toyota, they associate a significant share of success with their high discipline in terms of approach to solving problems. Sometimes this approach is called “thinking in A3 format” (knowledge gained during each “problem solving session” is recorded on sheets A3).

Here is an example and template:

www.crisp.se/gratis-material-och-guider/a3-template

With the “A3-approach”, a significant part of the time (left side of the sheet) is devoted to the analysis and visualization of the analysis of the root cause of the problem and precedes the development of any solutions . Causal charts are not the only method for analyzing root causes. There are also others: for example, the systematization of the value stream (value stream mapping) and the construction of the Ishikawa diagram, or, as it is also called, the “fishbone” diagram. Sample A3 above contains a value stream map (top left) and a causal diagram (bottom left).

Causal diagrams are good for their intuitiveness and no need for additional explanations (especially in comparison with the charts of “fish bone”). Another advantage is the ability to illustrate repetitive vicious cycles , which is extremely useful from the point of view of system thinking. Next, we will discuss how to effectively create and use such diagrams.

How to use cause-effect diagrams

The basic process is as follows:

- Choose a problem — anything that bothers you — and write it down.

- Trace its “ascending movement” to assess the implications for the business, the “obvious damage” your problem causes.

- Trace its “downward motion” to identify the root cause (or root causes).

- Identify and underline perverse cycles.

- Repeat the above steps several times to adjust the chart.

- Determine which of the root causes you will tackle, which methods you will do (which countermeasures can be taken).

The next stage is follow up. If the countermeasures worked, congratulations! If not - do not despair. Analyze why they did not work, update the diagram, taking into account the knowledge gained, and try other countermeasures.

In fact, countermeasures are not a solution, but an experiment . Your hypothesis is that countermeasures will solve (or minimize) the problem, but you can never be completely sure. In fact, you “poke a sharp stick” into your system, checking how it reacts. Therefore, follow up is important.

The error, in fact, means that your system sends you signals that you should listen to. The only real mistake is the inability to learn from mistakes!

Example 1: Lack of pair programming

One client asked to help him figure out why his business does not use XP techniques like pair programming and test-driven development (TDD). “We know we should do it, but we don’t,” said the client.

Is the lack of TDD and pair programming a real problem? As usual, often the things we call problems are not, but are just symptoms.

Q: What are the consequences of ignoring pair programming and TDD?

A: We believe that using these practices would improve the quality of the code.

Q: What are the consequences of poor code quality? Have you encountered real problems caused by poor code quality?

A: Yes, we got demos. Demo is a key element of our business, so this is a real problem.

OK, let's look at one of the elements and see if we can build a link to the very "basics".

Q: Why don't you practice pair programming?

A: Because many fear that it will not work and we will waste time. We have no proof that it works.

Q: What evidence do you need?

A: Well, we have seen studies that show that it is effective. But in our company, no one in fact tried to introduce such practices, so we are not sure of success.

Here is the first loop:

They do not want to introduce new practices, because they are not sure whether they will work. And they do not know if they are working, because they have not tried to implement them ...

Q: Why did you at least make no attempt to use pair programming as an experiment?

A: We have no time to experiment.

Q: Why?

A: Because we do not have a temporary reserve. Every hour accountable. And customers continue to overwhelm us with work.

Q: Why customers do not give you the opportunity to manage their time and consider it possible to pile on you work at any convenient time?

A: They do not trust us to independently allocate time.

The lack of trust also leads to the fear of failure in general, which, of course, reduces the likelihood of experimenting with new techniques like pair programming without guarantees that they will work.

It turns out that there are two global root causes: the lack of trust and the management setup for accounting each hour. Now back to the big picture.

The lack of trust between the client and the customer turned out to be the root cause of the fact that XP practices, such as TDD and pair programming, are not being introduced. This entails a bad quality, due to which the demos are crashed. And you would never guess: departing demo will reduce mutual trust even more. This is a vicious circle!

Interestingly, we performed this analysis during a two-day workshop with approximately 25 people. At the beginning, we mainly talked about technical things - how to get started with TDD and pair programming. This approach was not particularly effective; instead, we divided into groups and decided that each group chooses its own problem and begins to build a cause-effect diagram and formulate a solution to the problem on sheets A3. Interestingly, several groups, which analyzed at first glance different problems, eventually came to the same root cause: lack of trust. The diagram above is just one of the examples that illustrate this.

Thus, by the end of the master class, the conversation was about how to increase the degree of trust between the client and the developer. It was an unexpected turn of the workshop. For a start, we agreed that next time we will invite “them” (clients) to the workshop, which should reduce the frequency of the opposition “we” and “they”.

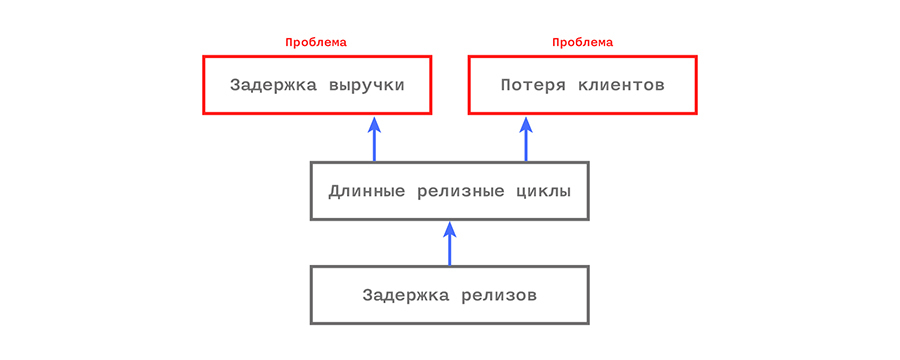

Example 2: long release cycle

Suppose we have a problem: we always break deadlines. More precisely, our releases always come out later than the scheduled time.

The problem is only a problem if it prevents you from achieving the goal. Therefore, the first step is to determine the goal and think about the consequences of the problem directly in the context of your goal. This will help the question “So what?”, Which must be asked until you can identify the obvious damage.

Suppose that the goal is to make customers happy and get maximum revenue. The dialogue may look something like this:

Q: “What is the negative effect of postponing releases? What could be the consequences? ”

A: “Delays make our release cycles long”

Q: “So what?”

A: “This postpones the receipt of revenue and negatively affects the speed of money in the company. We also lose customers because of their impatience. ”

In the process of dialogue, we add cells and cause-and-effect arrows to the diagram. Usually I try to move “ascending” from the originally stated problem, “mapping” its consequences. But this is not a strict rule.

That is, it turns out that the delay in releases is actually not a problem. True problems are revenue lag and loss of customers. At this stage it is necessary to consider three points:

Are there any other factors leading to loss of customers and revenue lag? If so, can we assume that all the delay in releases is to blame, or should we turn our attention to something else? Is it possible to quantify the problem? How much money have we lost? How many customers left? These data will help us estimate the amount of effort that justifies itself in solving the identified problem.

How do we understand what solved the problem? Suppose a happy consultant bursts into the office and proudly declares: “I solved the problem!”. How to determine that this is not a bluff?

After analyzing the consequences of the problem, it is time to dig deep into the root cause.

And here come the questions “Why”. Yes, there is a “five why” technique that you could hear about if you studied lean thinking.

Q: “Why are releases delayed?”

A: “Because the amount of work is growing.”

Q: “Why?”

A: “Because customers invent more and more new features and insist that they need to be added to the current release, refusing to exclude low priority features from it.”

Q: “Why? Why not postpone adding new features to new releases? ”

A: “Because the release cycle is so long that new requirements arise before the next release”

There are only three "Why." But you understood the principle. The dialogue allows you to form the following picture:

The vicious cycle is marked by red arrows. Repetitive problems almost always involve such “loops”, but it takes some time to identify them. If you have found such a loop, then the chances for a successful and irreversible solution to problems are many times greater!

Our goal is to identify the root cause of this problem so that we can achieve the maximum effect with minimal effort. At the first stage, you can easily overlook important reasons, so let's go back and ask some more questions.

Q: “Why is the release cycle long? Delayed releases - the only reason? ”

A: “Well, in fact, even without delay, our planned release cycles are quite long.”

Q: “How long is your planned release cycle?”

A: “Once a quarter.”

Q. “But why is it so long?”

A: “Because releases are expensive and complicated.”

Q: “Why?”

A: “Because in every release there are a lot of details and also because it’s manual work.”

On the left we see another vicious cycle (red arrows)! The long interval between releases means that each new version includes a large number of updates, which makes product release a complex and expensive process. Because of this, we don’t want to make releases often.

As you noticed, here I decided to note two primary causes. And now - countermeasures:

Root cause

Lack of automation in the release preparation process

Countermeasure

Automate the release process

Root cause

Low-priority features are not excluded from releases.

Countermeasure

Agree with the client that new features can be added to the release only if the same number of low-priority features is excluded from it.

There is no strict rule telling which reason is the root cause, but there are some signs:

- The cell has only outgoing arrows, but no incoming

- There is a feeling that from now on, digging deeper (asking additional “Why?”) Makes no sense

- The cell “has a solution” and may have a significant positive effect on the problem.

The “five why” technique is called so because usually there are about five questions that separate us from the original cause. There is a tendency to stop prematurely. Do not do this: keep digging!

It is necessary to take into account that the problem that was initially posed - delayed releases - in fact turned out to be neither a problem nor the root cause. It was just a symptom. We used it as a pretext to build a causal relationship upward to identify the true problem, and then downward to determine the root cause. This allows you to develop effective countermeasures with all your knowledge.

Without analysis of this type there is a risk to come to hasty conclusions and to make ineffective and counterproductive changes. For example, hiring additional employees, although the essence of the problem lies not in the amount of labor. Or by changing the reward system (encouraging people to do deadlines and penalizing late submission), although the existing reward system had nothing to do with the problem.

Example 3: defects in the production cycle

Imagine that we have problems with a defective code that runs in production.

Q: So what?

A: Defects anger our customers

Q: Why are defects run in production?

A: Because they did not pass the required testing prior to release.

Q: Why was there no testing?

Etc.

And that's what we get:

Two vicious cycles! Look at the red arrows.

Loop 1 (inner loop): Defects in the product force to make urgent changes, which distracts the team from work. Since employees are not exempt from the bulk of the tasks, they are under stress and do not have the time to properly test new releases. Which, of course, leads to an even greater number of defects at the level of the entire production.

Loop 2 (outer loop): Since employees are under stress, they also do not have time to write automatic test scripts. The consequence is a general lack of automation in testing, which increasingly complicates the regression testing of new releases. This, of course, leads to defects in production and the need to make urgent changes. And as a result - to even more stress.

But that's not all!

Teams hate it when they get distracted. The work process disrupts and ultimately kills motivation. This can be an explanation for the high turnover rates! Thus, by solving the underlying problem (defects in production), we get an additional bonus in the form of reducing staff turnover.

This is another advantage of causal analysis. Usually the root cause is the cause of more than one problem (which is why it is called “root” - primary or root).

Causal Analysis: Robots Experience

Boris Ryabchikov, Project Manager:

My task was to track down the problems existing in the company. We identified the main problem of production in advance. The hypothesis was as follows: we do not give up projects on time, and, as a result, the company has a low speed of money. A number of reasons were also excluded at the start: we assumed that the planning was carried out correctly, and the problem was somewhere else. The remaining problems were considered through this prism, and everything that was not relevant to the topic was simply discarded. We wanted to deal with the main problem and built a map based on this.

The production process was graphically marked: where we are and where we lose time and money.

First you had to choose the sources of information. In practice, it turned out that the most effective way is to collect problems individually with each employee. In retrospectives and standard reports, there are usually things that employees and so voiced with the entire team - at general meetings, with superiors. If a company has several divisions, they often compete with each other and “throw” problems at each other. When all employees come together, decency, as a rule, prevails and nobody blames each other’s faces. That is, problems can be hushed up. With individual interviews, they come to the surface.

I had to communicate with people in an informal setting - in the smoking room, on the road to the subway. Some problems were formulated in such conversations. As it turned out, the “method of five why” does not always work well in practice. Often, people get nervous about the numerous “why” and some immediately include protection. That is, in each case requires an individual approach.

The data obtained was gradually collected and entered into the diagram, which turned out to be rather large. According to the results of the analysis, I prepared a brief report, which identified four root causes and one main problem. All of them were grouped by competence centers in the company.

Work began with several root causes at the same time. With this approach, there is a risk of not understanding which of the root causes was the main one. But in this case he is justified.

Countermeasures were developed to eliminate the root causes and criteria for their success were identified. The next stage is the analysis of the intermediate result and the preparation of a new adjusted report. Often, the final solution to problems becomes a rather lengthy process.

Example 4: A whole bunch of problems

And here is a larger example. The organization used the Scrum methodology, but faced some problems. As a result of several interviews and workshops, a causal diagram was born, which showed that Scrum was actually used incorrectly in the team, which caused problems.

It became obvious to everyone that many of the root causes could be eliminated by the correct use of Scrum (for example, reorganization into cross-functional teams, confidence that there is a product owner in every team). This was the impetus for organizational change, which eventually eliminated many of the root causes (green stars). The next step was to improve test automation.

Of course, Scrum is not a panacea. In fact, sometimes Scrum itself is a problem and then other techniques are required for the solution, for example, Kanban .

Practical questions - how to create and maintain charts

Work alone

When I make diagrams one, the most convenient tools are Visio or Powerpoint. They allow you to quickly move elements, resize cells, and quickly make a backup while working on an image.

Work in small groups (2 - 8 people)

Gather near the board or flipchart. Instead of cells, use stickers, connecting them with hand-drawn arrows. The board is preferable, since you can erase and redraw the arrows on it as you move the stickers. Let all members of the group participate, not just one person. It is important not to forget to take a clear photo of what happened, and send it to all participants after the meeting.

Work in larger groups (9 - 30 people)

Let group members break up into small teams, each focusing on a specific problem. Working with several teams on the same problem is useful: you can come to the same or different conclusions, and both results will be interesting. Each team works with a separate flipchart / board and stickers. Periodically, teams should meet for short joint discussions and share experiences.

Work with a diagram in perspective

Let the diagram remain in the program you used: Visio or Powerpoint. If you decide to return to it again in the workshop, determine its purpose: to show the diagram or update it. If this is an update, repeat it on the board / flipchart with stickers and arrows, so that the workshop participants can work together effectively on the diagram. After the meeting, “synchronize” the results with electronic tools.

This type of synchronization takes some time, but often it is worth it. For collaboration, nothing surpasses real tools: a board and stickers.

Danger

Too many arrows and cells

It happens that a diagram becomes so chaotic that it cannot be disassembled. Then it should be simplified. Here are some techniques:

- (, ).

- “ ” “ ”. , , .

- . . “ , ”, .

- , : .

- , 3 .

Simplicity

- — . . , . , “ ” . : “” , .

:

, , . , . , : , , , , , . : .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/249907/

All Articles