The influence of cables on the parameters of the systems "amplifier-speaker" and "microphone-mixer"

The vast majority of audiophiles are confident in the significant influence of cables on sound. Many articles have been written on this topic, both by supporters and opponents of this theory, however, I have not met a single article containing real technical calculations that would prove this or that point of view. The texts usually provide their own speculation, which are sometimes far from reality. I used technical knowledge and calculations to understand this topic.

Most often, in addition to the active resistance of the conductor, audiophiles mention three factors that supposedly affect the final parameters of the electrical circuit:

Consider the first two factors together, because they have a very close relationship.

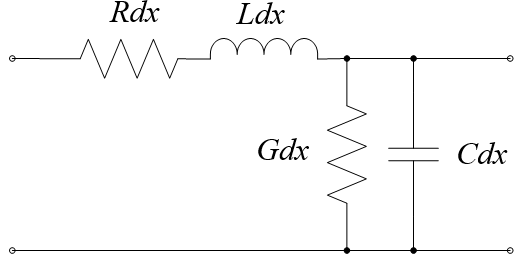

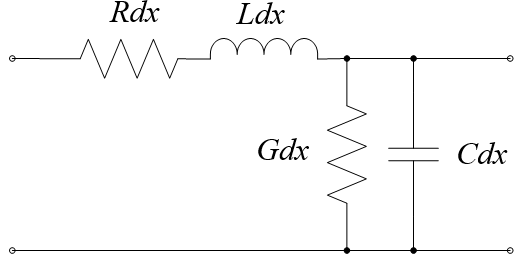

The fact is that there is an equivalent circuit of an infinitely small segment of a long power line, which is a quadrupole containing linear resistance, capacitance, inductance and conductivity (Figure 1). Thus, any long line is a collection of data of four-port networks connected in series.

Figure 1 - Equivalent scheme of an infinitely small segment of a long line

However, here it should be borne in mind that we are talking about a long line. By definition, a long line is a regular power line, the length of which is many times longer than the wavelength of the oscillations propagating in it, and the distance between the conductors and the transverse size of the conductors are many times smaller than the wavelength, i.e. relations are fulfilled

where λ is the wavelength, L is the line length, a is the conductor cross section, b is the distance between the conductors. For the upper boundary frequency ν = 20,000 Hz of the audible range, the wavelength λ = c⁄ν , where c is the speed of light, will be equal to 3,000,000,000 / 20,000 = 15,000 m, or 15 km. For a frequency of 50 Hz, the wavelength will reach six thousand kilometers. Naturally, such lengths of acoustic cables are not used, and therefore the long line model is clearly not suitable for them.

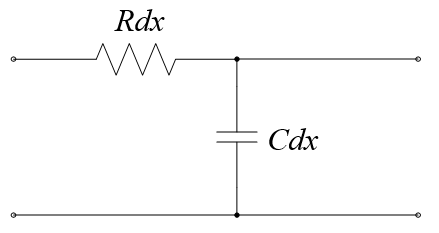

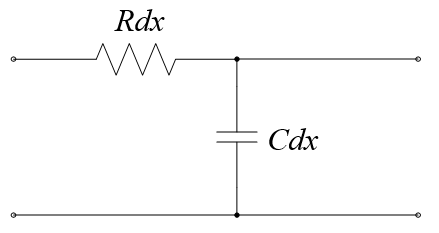

For lines that are much shorter or comparable with the wavelength of the oscillations, there is an equivalent circuit of a short line (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Equivalent scheme of an infinitely small segment of a short line

')

As can be seen from the figure, the conductivity and inductance of the line are no longer taken into account here, since their values are negligible (for a short line). This means that there is no point in considering the second factor. Only capacity remains.

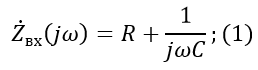

We now calculate the input and output impedances of our passive quadrupole and see its transfer characteristic.

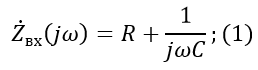

The input impedance for the first circuit will be:

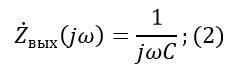

Output resistance for the second circuit:

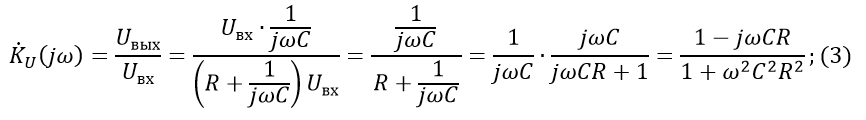

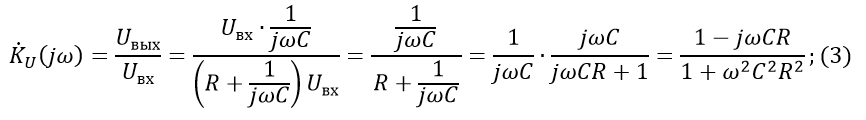

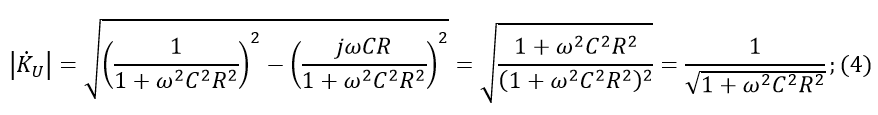

Voltage transfer characteristic:

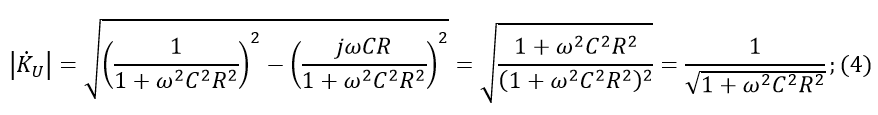

Transfer characteristic module:

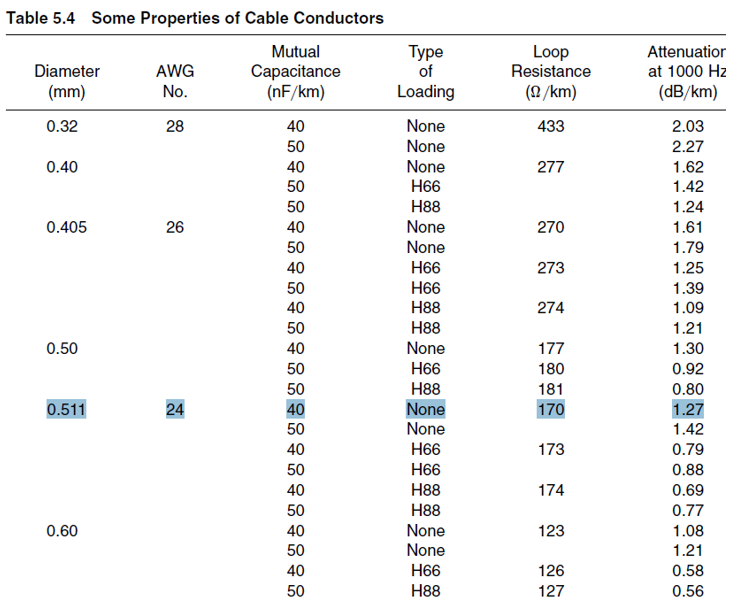

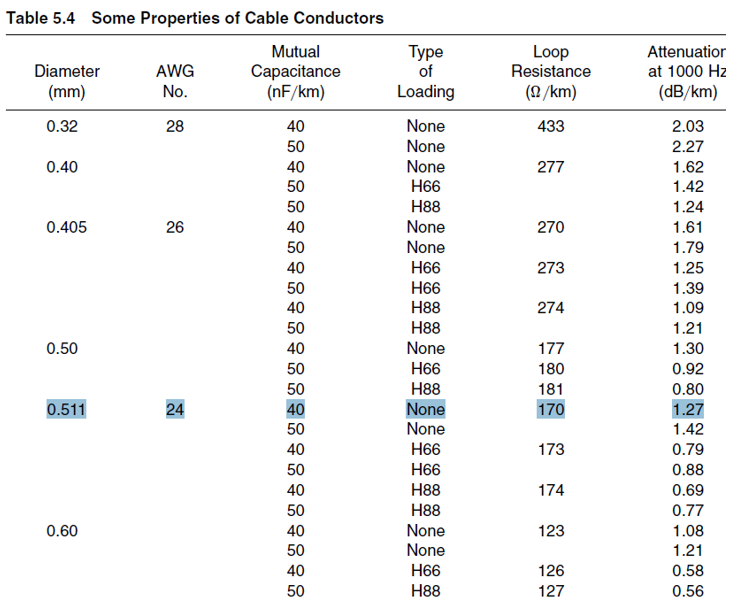

Now we take for calculation one meter of some real cable. I went to audiomania.ru and found a cheap Onetech Rapid Two INT0107 microphone cable. One conductor of this cable has a cross section of 0.21 sq. Mm, which approximately corresponds to the AWG 24 caliber, according to the American standard. From the book Fundamentals of Telecommunications we will use the table, in which the running resistances and capacities are indicated (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Cable parameters table (for 1 kHz)

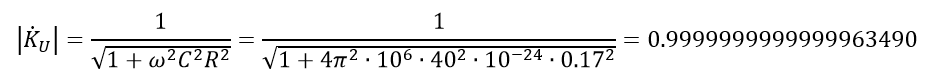

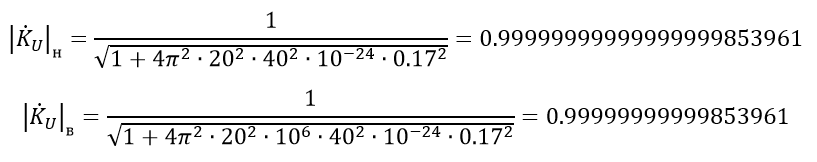

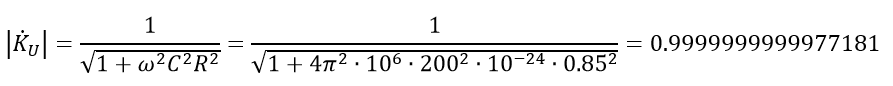

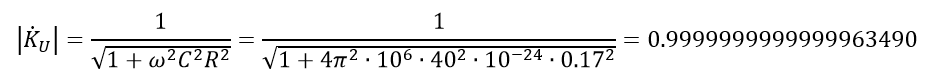

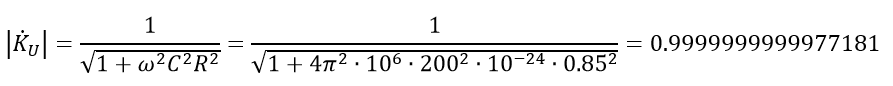

For AWG 24, C = 40 nF⁄km = 40 pF⁄m; R = 170 Ohm⁄km = 0.17 Ohm⁄m, ν = 1000 Hz. Substitute these values in the formula (4):

I deliberately left more than 15 decimal places to show how meager the change in voltage as it passes through the quadrupole. By the way, it is difficult to even find a device that will show such accuracy.

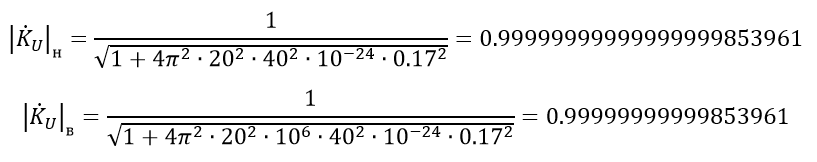

Let us now look at the boundary value of the spectrum of frequencies perceived by the human ear ( ν_n = 20 Hz, ν_v = 20000 Hz):

Skeptics will say: “This is a calculation for just one meter of cable.” Well, let's see what happens with the voltage transfer characteristic module for, say, five meters of cable (for 1 kHz).

Changes for five meters of cable are still negligible to accommodate.

By definition, the skin effect (or surface effect) is the effect of decreasing the amplitude of electromagnetic waves as they penetrate deep into the conducting medium. As a result of this effect, for example, an alternating current of high frequency when flowing through a conductor is not distributed evenly over the cross section, but mainly in the surface layer. It is due to the non-uniform current distribution the effective conductor cross-section decreases, and, consequently, the resistance increases.

This idea of the skin effect causes audiophiles to buy silver-plated wires, which, naturally, are much more expensive than usual (using a thin layer of silver you can really deal with the skin effect for high frequencies, due to the lower resistivity of silver). But does it make sense?

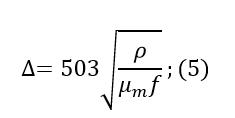

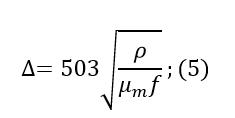

The derivation of the formula describing the skin effect is based on Maxwell’s equation. It does not make sense to paint it; all information can be found in textbooks for universities (for example, in the Sivukhin textbook). Instead of output, we use the simplified formula to calculate the thickness of the skin layer (the layer in the conductor, where almost the entire current is concentrated):

where ρ is the resistivity, μ_m is the relative magnetic permeability, f is the frequency.

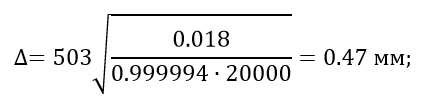

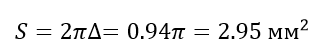

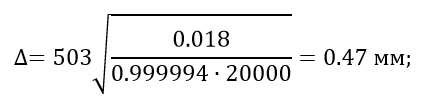

For copper: ρ = 0.018 (Ohm sq.mm) / m; μ_m = 0.999994 at a frequency of f = 20,000 Hz:

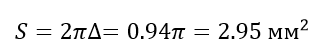

We calculate the cross-sectional area in which we have a skin effect:

Thus, for any wire gauge that has a cross-sectional area smaller than 2.95 sq. Mm, the skin effect has no effect at all.

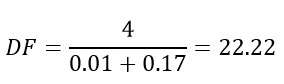

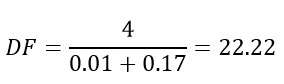

Many lovers of good sound often refer to the damping factor (or damping factor), allegedly described in the German standard DIN 45500 and defining it as the ratio of the load resistance to the output impedance of the amplifier. It is believed that the system falls under the definition of Hi-Fi, if its damping factor is more than 20. At the same time, the coefficient allegedly takes into account the cable resistance (it is summed up with the output impedance of the amplifier), and only its active part. If you use this factor, it turns out that the resistance of the conductors not only has a tremendous impact on the speakers, but is almost one of the most important parameters of the speakers. For example, let's take the output impedance of the amplifier equal to 0.01 Ohm, then, when connecting the speaker to 4 Ohms with an AWG 24 cable of 1 meter length, we get:

The damping coefficient barely exceeded 20, and this is only for one meter of cable! What is the matter and who to believe?

Honestly, I did not read the standard DIN 45500, because it is written in German, which I do not speak. However, in Russian national standards there are two analogs of this DIN 45500 for speakers and amplifiers - GOST 23262-88 and GOST 24388-88, respectively. None of them has a “damping coefficient”, which is never mentioned, as in other GOST standards, references to which are present in them. This term is also not found in the Russian-language literature. In English-speaking resources, information about this parameter is available, but rather scarce, without references to authoritative sources.

Based on a study conducted at the beginning of the article, I’m pretty sure that the “damping coefficient” is nothing more than a myth invented by marketers to increase sales of thick and silver-plated cables, worth hundreds or even thousands of dollars. They tried to adjust the matching of voltages in acoustic systems to a certain parameter, however, the damping coefficient does not characterize the speakers either quantitatively or qualitatively.

Although initially the article looked at the impact on the speaker system, the topic of guitar combos and cables for connecting electric guitars to them surfaced in the comments. It should be noted that this topic requires a slightly different approach to consideration. And that's why.

Any “amplifier-speaker” or “microphone-mixing console” system requires matching of the resistances by voltage : the load resistance must be much greater than the resistance of the source output (in other words, the internal resistance of the signal source). In this case, the voltage, which is the carrier of the signal, will pass from the source to the load with minimal losses. It is to this type of agreement, in the first place, the article.

With guitar combos the story is a bit different. Here, due to the characteristics of the electric guitar pickup, power matching is used. In this case, the load resistance must be complexly coupled with the internal resistance of the source (or be close to this state).

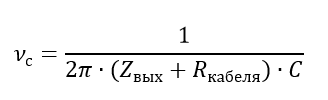

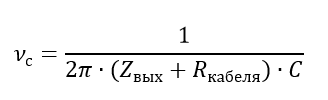

With any type of matching for any signal source, the cable is the simplest low-pass filter. The formula for determining the cutoff frequency is as follows:

This can be considered an additional limitation that is imposed on the entire system. In the case of voltage matching, the cutoff frequency will be very high: a lot more than the upper limit frequency of the sound spectrum. The output resistance of an electric guitar can reach hundreds of thousands of kOhms (I did not find a more accurate interval in the technical literature), here the cut-off frequency may be within the audio spectrum. Since the internal resistance of the source is very large, the cable resistance for this formula can be neglected, that is, the most important parameter for such a “guitar” cable is the linear capacitance. It should be noted that no other phenomena are introduced by the cable into the system, that is, up to the cut-off frequency, the transfer characteristic calculated above is valid.

I want to note that the capacity of a cable made of copper conductors is determined solely by the geometry , that is, the relative position of the conductors and their linear dimensions (the insulation material, i.e., the dielectric, is not taken into account, since the variation in the dielectric constant values of the materials used is relatively small). This means that there are no special manufacturing techniques for cables that increase the cost to tens of thousands of rubles or more.

From the output of the combo amplifier, the resistance is matched with the voltage resistance of the console using the DI Box. Connecting an electric guitar without a DI Box will result in a strong signal distortion.

The calculations in this article clearly show that the influence of cables on the transmission of signals in the frequency spectrum heard by the human ear for amplifier-speaker systems and microphone-mixer systems is negligible. For these systems, there are two types of cables: working and non-working.

In this case, special attention should be paid to the capacity for cables connecting electric guitars to combo amplifiers, since the cut-off frequency of the “guitar-combo” system depends on it.

However, one thing is certain: the cables do not contribute any “color”, “mood” or other things that sellers or audiophiles like to say so much about.

I dare say that in no case can I affect your freedom of choice in any way - you can buy any cables at any price and for any reason. I wrote all this only as an act of resistance to the spread of technical heresy, which too often began to be introduced by marketers for the sake of making easy money.

List of used sources

1. L.A. Bessonov. Theoretical foundations of electrical engineering. Electrical circuits. - M .: Higher School, 1996. - 638 p.

2. D.V. Sivukhin. General course of physics. Electricity. V. III - M .: Science, 1977. - 704 p.

3. A.N. Matveyev. Electricity and magnetism. - M .: Higher School, 1983. - 463 p.

4. A.V. Maksimychev. Physical research methods. Lecture notes. Part 2. Signals in long lines. - M .: MIPT, 2003. - 43 p.

5. GOST 23262-88. Household acoustic systems. General technical conditions.

6. GOST 24388-88. Amplifiers audio signals household. General technical conditions.

7. GOST 16122-87. Loudspeakers. Methods of measurement of electroacoustic parameters.

8. Roger L. Freeman. Fundamentals of Telecommunications. - John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1999. - 676 p.

9. Zernov N.V., Karpov V.G. Theory of radio circuits. - M. - L .: Energy, 1965. - 892 p.

10. Jones MH Electronics - a practical course. - M .: Technosphere, 2006. - 512 p.

Most often, in addition to the active resistance of the conductor, audiophiles mention three factors that supposedly affect the final parameters of the electrical circuit:

- capacitive resistance (since the cable consists of a pair of conductors);

- inductive resistance;

- skin effect.

Consider the first two factors together, because they have a very close relationship.

The fact is that there is an equivalent circuit of an infinitely small segment of a long power line, which is a quadrupole containing linear resistance, capacitance, inductance and conductivity (Figure 1). Thus, any long line is a collection of data of four-port networks connected in series.

Figure 1 - Equivalent scheme of an infinitely small segment of a long line

However, here it should be borne in mind that we are talking about a long line. By definition, a long line is a regular power line, the length of which is many times longer than the wavelength of the oscillations propagating in it, and the distance between the conductors and the transverse size of the conductors are many times smaller than the wavelength, i.e. relations are fulfilled

where λ is the wavelength, L is the line length, a is the conductor cross section, b is the distance between the conductors. For the upper boundary frequency ν = 20,000 Hz of the audible range, the wavelength λ = c⁄ν , where c is the speed of light, will be equal to 3,000,000,000 / 20,000 = 15,000 m, or 15 km. For a frequency of 50 Hz, the wavelength will reach six thousand kilometers. Naturally, such lengths of acoustic cables are not used, and therefore the long line model is clearly not suitable for them.

For lines that are much shorter or comparable with the wavelength of the oscillations, there is an equivalent circuit of a short line (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Equivalent scheme of an infinitely small segment of a short line

')

As can be seen from the figure, the conductivity and inductance of the line are no longer taken into account here, since their values are negligible (for a short line). This means that there is no point in considering the second factor. Only capacity remains.

We now calculate the input and output impedances of our passive quadrupole and see its transfer characteristic.

The input impedance for the first circuit will be:

Output resistance for the second circuit:

Voltage transfer characteristic:

Transfer characteristic module:

Now we take for calculation one meter of some real cable. I went to audiomania.ru and found a cheap Onetech Rapid Two INT0107 microphone cable. One conductor of this cable has a cross section of 0.21 sq. Mm, which approximately corresponds to the AWG 24 caliber, according to the American standard. From the book Fundamentals of Telecommunications we will use the table, in which the running resistances and capacities are indicated (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Cable parameters table (for 1 kHz)

For AWG 24, C = 40 nF⁄km = 40 pF⁄m; R = 170 Ohm⁄km = 0.17 Ohm⁄m, ν = 1000 Hz. Substitute these values in the formula (4):

I deliberately left more than 15 decimal places to show how meager the change in voltage as it passes through the quadrupole. By the way, it is difficult to even find a device that will show such accuracy.

Let us now look at the boundary value of the spectrum of frequencies perceived by the human ear ( ν_n = 20 Hz, ν_v = 20000 Hz):

Skeptics will say: “This is a calculation for just one meter of cable.” Well, let's see what happens with the voltage transfer characteristic module for, say, five meters of cable (for 1 kHz).

Changes for five meters of cable are still negligible to accommodate.

About skin effect

By definition, the skin effect (or surface effect) is the effect of decreasing the amplitude of electromagnetic waves as they penetrate deep into the conducting medium. As a result of this effect, for example, an alternating current of high frequency when flowing through a conductor is not distributed evenly over the cross section, but mainly in the surface layer. It is due to the non-uniform current distribution the effective conductor cross-section decreases, and, consequently, the resistance increases.

This idea of the skin effect causes audiophiles to buy silver-plated wires, which, naturally, are much more expensive than usual (using a thin layer of silver you can really deal with the skin effect for high frequencies, due to the lower resistivity of silver). But does it make sense?

The derivation of the formula describing the skin effect is based on Maxwell’s equation. It does not make sense to paint it; all information can be found in textbooks for universities (for example, in the Sivukhin textbook). Instead of output, we use the simplified formula to calculate the thickness of the skin layer (the layer in the conductor, where almost the entire current is concentrated):

where ρ is the resistivity, μ_m is the relative magnetic permeability, f is the frequency.

For copper: ρ = 0.018 (Ohm sq.mm) / m; μ_m = 0.999994 at a frequency of f = 20,000 Hz:

We calculate the cross-sectional area in which we have a skin effect:

Thus, for any wire gauge that has a cross-sectional area smaller than 2.95 sq. Mm, the skin effect has no effect at all.

About the damping ratio

Many lovers of good sound often refer to the damping factor (or damping factor), allegedly described in the German standard DIN 45500 and defining it as the ratio of the load resistance to the output impedance of the amplifier. It is believed that the system falls under the definition of Hi-Fi, if its damping factor is more than 20. At the same time, the coefficient allegedly takes into account the cable resistance (it is summed up with the output impedance of the amplifier), and only its active part. If you use this factor, it turns out that the resistance of the conductors not only has a tremendous impact on the speakers, but is almost one of the most important parameters of the speakers. For example, let's take the output impedance of the amplifier equal to 0.01 Ohm, then, when connecting the speaker to 4 Ohms with an AWG 24 cable of 1 meter length, we get:

The damping coefficient barely exceeded 20, and this is only for one meter of cable! What is the matter and who to believe?

Honestly, I did not read the standard DIN 45500, because it is written in German, which I do not speak. However, in Russian national standards there are two analogs of this DIN 45500 for speakers and amplifiers - GOST 23262-88 and GOST 24388-88, respectively. None of them has a “damping coefficient”, which is never mentioned, as in other GOST standards, references to which are present in them. This term is also not found in the Russian-language literature. In English-speaking resources, information about this parameter is available, but rather scarce, without references to authoritative sources.

Based on a study conducted at the beginning of the article, I’m pretty sure that the “damping coefficient” is nothing more than a myth invented by marketers to increase sales of thick and silver-plated cables, worth hundreds or even thousands of dollars. They tried to adjust the matching of voltages in acoustic systems to a certain parameter, however, the damping coefficient does not characterize the speakers either quantitatively or qualitatively.

On the coordination of resistances and "guitar" cables

Although initially the article looked at the impact on the speaker system, the topic of guitar combos and cables for connecting electric guitars to them surfaced in the comments. It should be noted that this topic requires a slightly different approach to consideration. And that's why.

Any “amplifier-speaker” or “microphone-mixing console” system requires matching of the resistances by voltage : the load resistance must be much greater than the resistance of the source output (in other words, the internal resistance of the signal source). In this case, the voltage, which is the carrier of the signal, will pass from the source to the load with minimal losses. It is to this type of agreement, in the first place, the article.

With guitar combos the story is a bit different. Here, due to the characteristics of the electric guitar pickup, power matching is used. In this case, the load resistance must be complexly coupled with the internal resistance of the source (or be close to this state).

With any type of matching for any signal source, the cable is the simplest low-pass filter. The formula for determining the cutoff frequency is as follows:

This can be considered an additional limitation that is imposed on the entire system. In the case of voltage matching, the cutoff frequency will be very high: a lot more than the upper limit frequency of the sound spectrum. The output resistance of an electric guitar can reach hundreds of thousands of kOhms (I did not find a more accurate interval in the technical literature), here the cut-off frequency may be within the audio spectrum. Since the internal resistance of the source is very large, the cable resistance for this formula can be neglected, that is, the most important parameter for such a “guitar” cable is the linear capacitance. It should be noted that no other phenomena are introduced by the cable into the system, that is, up to the cut-off frequency, the transfer characteristic calculated above is valid.

I want to note that the capacity of a cable made of copper conductors is determined solely by the geometry , that is, the relative position of the conductors and their linear dimensions (the insulation material, i.e., the dielectric, is not taken into account, since the variation in the dielectric constant values of the materials used is relatively small). This means that there are no special manufacturing techniques for cables that increase the cost to tens of thousands of rubles or more.

From the output of the combo amplifier, the resistance is matched with the voltage resistance of the console using the DI Box. Connecting an electric guitar without a DI Box will result in a strong signal distortion.

Conclusion

The calculations in this article clearly show that the influence of cables on the transmission of signals in the frequency spectrum heard by the human ear for amplifier-speaker systems and microphone-mixer systems is negligible. For these systems, there are two types of cables: working and non-working.

In this case, special attention should be paid to the capacity for cables connecting electric guitars to combo amplifiers, since the cut-off frequency of the “guitar-combo” system depends on it.

However, one thing is certain: the cables do not contribute any “color”, “mood” or other things that sellers or audiophiles like to say so much about.

I dare say that in no case can I affect your freedom of choice in any way - you can buy any cables at any price and for any reason. I wrote all this only as an act of resistance to the spread of technical heresy, which too often began to be introduced by marketers for the sake of making easy money.

List of used sources

1. L.A. Bessonov. Theoretical foundations of electrical engineering. Electrical circuits. - M .: Higher School, 1996. - 638 p.

2. D.V. Sivukhin. General course of physics. Electricity. V. III - M .: Science, 1977. - 704 p.

3. A.N. Matveyev. Electricity and magnetism. - M .: Higher School, 1983. - 463 p.

4. A.V. Maksimychev. Physical research methods. Lecture notes. Part 2. Signals in long lines. - M .: MIPT, 2003. - 43 p.

5. GOST 23262-88. Household acoustic systems. General technical conditions.

6. GOST 24388-88. Amplifiers audio signals household. General technical conditions.

7. GOST 16122-87. Loudspeakers. Methods of measurement of electroacoustic parameters.

8. Roger L. Freeman. Fundamentals of Telecommunications. - John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1999. - 676 p.

9. Zernov N.V., Karpov V.G. Theory of radio circuits. - M. - L .: Energy, 1965. - 892 p.

10. Jones MH Electronics - a practical course. - M .: Technosphere, 2006. - 512 p.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/248497/

All Articles