As the world's first computer saved from oblivion at the dump

It is difficult to surprise eccentric billionaires with something, therefore, getting vague tasks, their assistants should always think big. People who work for Ross Perot did just that when in 2006 their boss announced that he wanted to decorate his office in Plano, Texas [a suburb of Dallas - hereinafter approx. trans. ] "Relics" from the world of computing technology. Knowing that a few pathetic Apple I and Altair 880 would not be enough to satisfy the former presidential candidate, his staff decided to target larger fish and find a large block from ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer, Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator).

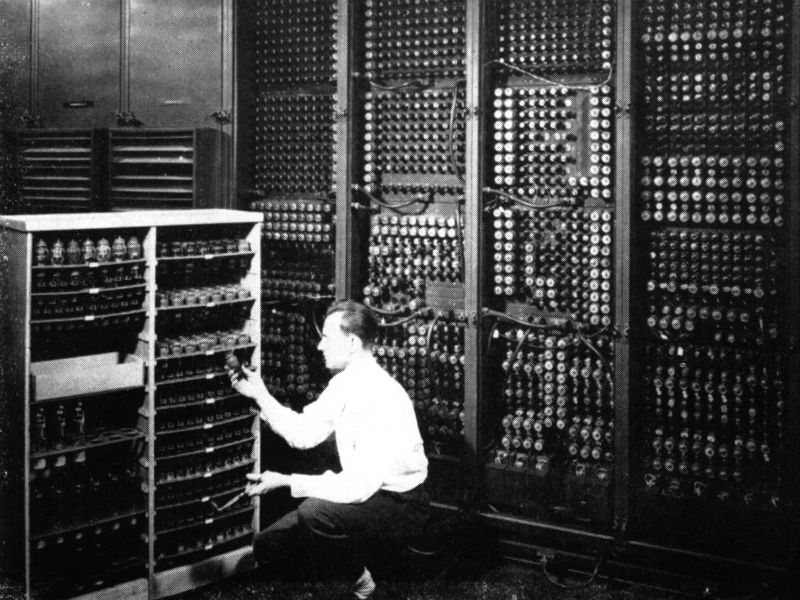

ENIAC, a 27-ton bundle of vacuum tubes and diodes, covering an area of 1,800 square feet [approx. 167 sq. M.], Is considered the world's first real computer (although some call this statement controversial). That part of this computer, which Perot’s assistants have spotted and restored with love, is now for the first time put on public display at the same military base where ENIAC has practically rotted, remaining in oblivion.

')

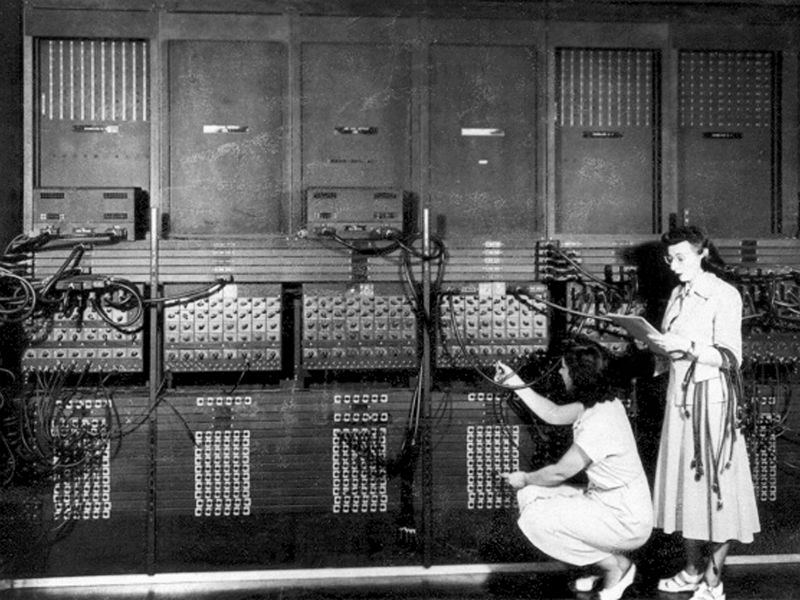

Computer ENIAC, 1946

ENIAC was conceived at the height of the Second World War as a means to help gunners calculate the trajectory of the projectiles. Although its assembly began a year before D-Day [the day the Allied army landed in Normandy, June 6, 1944 ], the computer first started working only in November 1945, when the thunder of guns from the US armed forces had subsided. But the military continued to see prospects for the use of ENIAC, since the Cold War began — the car with 17,468 vacuum tubes was taken up by the creators of the first hydrogen bomb, who needed to test the capabilities of their early designs. Scientists from Los Alamos later stated that they could not have achieved success without the incredible computing power of ENIAC: the machine could perform 5,000 operations per second — this made it thousands of times faster than the electromechanical computers of that time (by the way, the iPhone 6 can perform 25 billion operations per second).

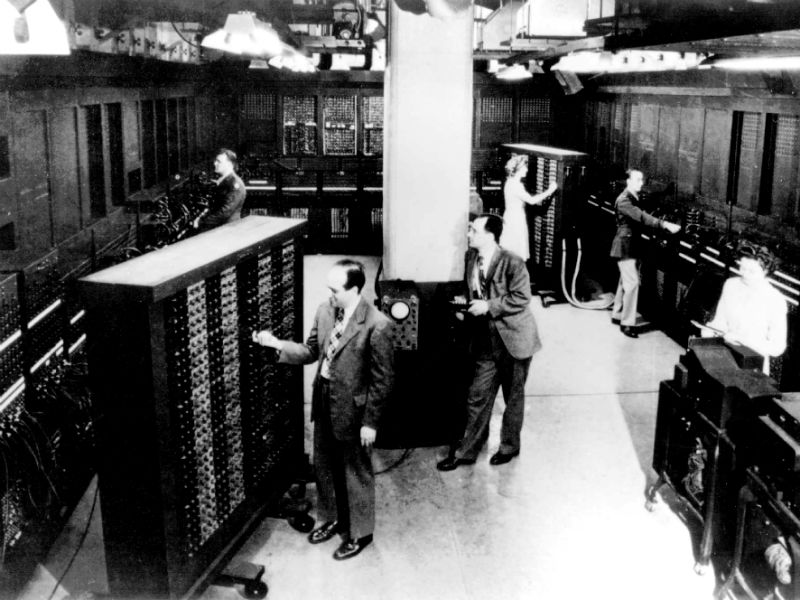

J. Presper Eckert and John W. Mockley with an ENIAC computer. University of Pennsylvania, 1946

However, when the army declared ENIAC obsolete in 1955, the historical invention was treated without due respect: 40 computer panels, each of which weighed about 858 pounds [ almost 390 kg. ], divided and stored without great care. Some of the hardware remained in the hands of those who appreciated the importance of the machine: for example, engineer Arthur Berks donated his panel to the University of Michigan, and the Smithsonian Institution tried to acquire a pair of panels for his own collection. But as to their chagrin, Libby Carft, director of special projects Perot, had to admit, most of ENIAC disappeared in scattered warehouses almost like the Ark of the Covenant at the end of the film Indiana Jones: In Search of the Lost Ark.

Lost under tons of papers

“Time passed, and new employees, coming to the warehouses, inherited logbooks that were not kept as good as they should,” said Kraft, who was the main person responsible for finding what was left of ENIAC. “And when they needed extra space, they could well pay attention to a pile of metal, about which they knew nothing. And then they could easily get rid of it. ”

Kraft was on the verge of stopping the search when an army officer searched for documents showing that part of the panels had once been transported from the test site in Aberdeen (Maryland) to Fort Sill in Oklahoma to the military museum of field artillery. When Kraft contacted Fort Sill to make inquiries, the museum curator was shocked to learn that the museum had the largest ENIAC unit in the world - a total of nine panels, all of which were stored in unnamed wooden boxes that no one had opened many years. Representatives of Fort Sill do not know how they turned out to be almost a quarter of the ENIAC computer, part of which was brought to Oklahoma from the Military Depot in Anniston (Alabama).

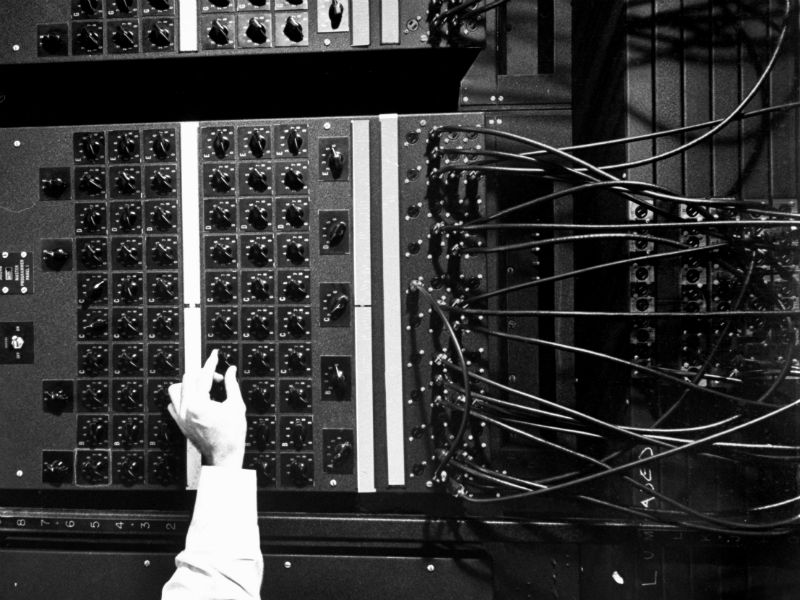

ENIAC technician changes the bulb

Kraft made a deal according to which her company could borrow panels from Fort Sill in exchange for a promise to restore the apparatus before reaching external similarity with its former greatness. The restoration project was led by Dan Gliison, an engineer at Perot Systems, who had no experience repairing vintage computers. Gleason quickly found out that he couldn’t force the received part of ENIAC to perform real operations - all 40 panels would be needed for this, not to mention the thousands of new components and technical knowledge that were lost long ago. But he was able to ensure that the computer at least outwardly looked so that it became clear: to calculate the ideal trajectory of the projectile from a howitzer is not an easy task.

Restoration and return home

First of all, Gleason tried to remove the cosmetic defects of the panels - the metal of the outer shell strongly rusted (one of the eight panels was so badly damaged by moisture that it was not possible to save it). Gleason sanded the panels with a sandblaster, then covered them with black high-temperature paint, which he bought from dozens of service shops and service stations. When the paint dried, Gleason and his son, Jonathan, painstakingly began to solder 600 new lamps to the panels. The lamps were connected to the motion sensor, so they began to light up randomly when a visitor appeared. Gleason also made a large steel frame, which did not allow the panels to tip over, and the electrical tubes protruding on the sides (not to mention what the falling panel could do to a person who happened to be by chance).

The renewed ENIAC took place in the Perot office in 2007, but relatively few could see it there — the office was in a protected room, to which no entry was allowed, although several enthusiasts were able to obtain permission to conduct special excursions . But not so long ago, the Perot company, which Dell swallowed up in 2009, announced that it would soon undertake a new stage of search - so it was time to return the panels to Fort Sill. Plast history of computers weighing 6,864 pounds [ more than 3,113 kg. Wrapped in the mountains of bubble wrap, he made his way back to Oklahoma at the end of September. Since Dan Gleason prudently used simple blade-type connectors and widely used 12-channel DMX controllers to connect lamps, Fort Sill Museum easily brought the design to a working state. The hardest thing was to assemble the steel frame, which turned out to be harder than the museum staff expected.

The ENIAC panels began to show visitors to Fort Sill in late October, although the exhibit still requires some restoration work. The museum, in particular, is in the process of acquiring additional electronic tubes in order to give the device a more “natural” look. Panels, of course, will never be able to make real calculations, but this is probably for the best. Even during its active use, ENIAC had to spend as much as 30 milliseconds to calculate the square root of a complex number. Who would have the patience for it now?

Posts and related links:

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/246787/

All Articles