Information objects or the reason for one misconception

Introduction

In the last article, we looked at the concept of a functional object and looked at how its parts are modeled. Today I want to talk about how the information object is interpreted in the logical paradigm, and what follows from this. In addition, we will see how one entertaining misconception was born: the idea that the terms object and object instance allegedly point to different objects in the subject area. And understand the causes of this error.

Terms

Immediately, I note that I do not claim their correctness. The trouble is that I could not find consistent definitions of the model and information in any of the dictionaries. Since the field of human mental functions is not my element, I most likely do not know the exact definitions of these terms. However, it was important for me to emphasize the idea that information and a model are what exist in the imagination of the subject, and in objective reality only their representations. Therefore, I introduce working definitions without claiming their accuracy.

')

- The model is what somehow answers the questions about the object of interest to us and has a different degree of detail. Even the name will be considered as a model by us, because it carries important information about the object. It says that the object exists.

- Information is a model of some part of reality that exists in the minds of people (man).

- An information object is a representation of a model in the material form necessary for storing information and transferring it to other people.

Examples of information objects

Models exist only in the minds of people, but the exchange of models occurs, as a rule, with the help of physical objects playing the role of information (we consider the generally accepted European methods of transmitting information, and do not consider mystical ones). These physical objects are called information representations, or model representations.

Let me remind you that we work in 4-D space, where objects exist in time, and time does not exist without objects. Examples of information objects can be Contract, Ticket, Billboard, Bill, Book, Electrical Voltages at the output of the contact group, Speech, Film. For example, speech is sound vibrations, therefore it is also a physical 4-D object. Every year the number of physical objects that were created for the sole purpose of carrying information is becoming more and more. In primitive society, the amount of information transmitted from subject to subject was small. Now it is a huge stream. However, even now the nature of information objects for many remains a mystery. I propose to try to deal with this issue.

In the world, we work exclusively with information objects, which are only representations of models, but not the models themselves. This distinction introduced the ISO 15926 standard to distinguish the model in the head from its presentation as a material carrier. Although very often the model in the heads and the information object we do not distinguish and we call it the same name - the model.

For example, a bill is an information object, which is designed to store information about what the owner of this bill can afford to do. And it is not necessary to make a purchase of goods in the store. It may also be possible to perform some other action. Information about what the owner can afford exists in our heads, the bill itself only represents this information in the form of a material object. The paper itself, apart from the social agreement about it, has no value. In order for a note to have value, there must be some generally accepted model in the heads of people who make up a certain social group. This is reflected in its informational nature. On the other hand, the piece of paper itself is a physical object. This piece of paper may well be the cause of the death of the fly, if you use the bill as a fly swatter. By the way, then the piece of paper will play the role of a functional object fly swatter. This will mean that the same paper atoms at the same time played the role of both the information object and the functional one. But that is not all. Let you have a bill and let this bill be torn. You go to the bank, and you are given a new bill in exchange for the banknote that has lost its appearance. Information about what is permissible to you has not changed. The carrier of this information has changed. Consequently, many information objects can represent one model.

With all this intersection of objects, the logical paradigm, which replaced the Aristotelian logic, was to cope.

Another example. Let there be an agreement between two legal entities. The model of this agreement is a model in the minds of those who participated in the achievement of this agreement. The representation of this model is a paper document, on which there are signatures of officials. There are many such paper documents: at least two - one for each side. Question: Do these two paper documents have one object, or two? A seemingly simple question turns out to be very difficult for modern analysts. We will return to it later.

What is stored in the database?

An information object is an object that stores information about objects (including information objects). Only information objects are stored in the database. These objects are objects in the form of magnetized domains, for example. They are designed to store information about other objects. What information is stored in those objects that are called a contract and invoice in databases? About contracts and invoices? Then it will mean that the system stores information objects that store information about other information objects — contracts and invoices. Or about real arrangements and about real deliveries? Then it will mean that the system stores information objects that store information about real objects: contracts and supplies. What do they actually store information about? To understand these issues is very difficult. Perhaps, in one of the articles I will talk about how information about different parts of the subject area, mixed with information about other parts of it and information about information objects, is “smeared” over the data structure. And about the reasons for this.

4 models for creating an information object

Let's see which models we need to create an agreement model (in our head).

- The model agreement is based on industry norms and rules. These rules fix the terms that need to be used when creating a model agreement, those events that need to be negotiated by the parties (supply of parts), and those events that will occur regardless of whether they are written in the contract or not (signing invoices, for example) . These norms are model 1 (it can also be called a context). These models are owned by lawyers and accountants. They are presented in legislation.

- Based on model 1, we create a model 2 - a model of the agreement itself.

- Now it is necessary to fix the agreement model in the form of a presentation, that is, on a tangible medium. What models need to know to do this? For this we need to have a model that describes how the model of the arrangement should be presented. This information can be found in special regulatory documentation. This is model 3.

- And fourth, you need to know how we will distinguish between contracts that model one agreement (Different copies of an agreement) - model 4.

Having these four models, we can create a concrete representation of model 2 of a specific agreement (a copy of the contract). The terms used, the relationships between them, the default events will be taken from model 1, legal details and other data from model 2, the structure of the text and its design from model 3, the accounting of signed copies from model 4. A total of 4 models are needed to create one copy of the contract. Two of them belong to the domain model. And two - to the representation of the model. Such a division into models is universal for the representation of any information object. If you have an information object, look for 4 models that are always somewhere nearby.

The difference between the terms object and object instance

So, after all, different pieces of paper with seals - are they different objects or the same? Last time I hear the answer: this is one object, but the instances of this object are different! The reason for the deformation that led to this kind of response, we should find out.

Story:

A business analyst is sitting opposite me and just a man from the street. I show the analyst the operation: I bring a cup of tea to my mouth and take a sip. I ask the analyst: “Can we call this an operation?” - Yes, of course. Then I repeat the same actions and ask the analyst: Can this action be called an operation? The answer is yes. I ask: are these different operations, or one? The analyst cheerfully answers: one, of course! The operation is one, and there are many instances of it. The man from the street moved his brow a little. Then I ask further: We have 100 athletes in front of us, all as one in shorts and t-shirts. Is this one athlete, or many athletes? The answer is: a lot of athletes? And what do they have in common, I ask. The appearance of them - the general, was the answer. Well, why then the operation is one? The analyst pondered. I explain: there are many operations, but their appearance is the same! Right? Doubts ... Then I continue: they have a general description, and the operations are different. Well, of course! The operation description is one, and there are many operations that satisfy this description.

If you think about it, the analyst's answer seems to an outside observer ridiculous. Verified! However, modern analysts often resort to this interpretation, and this has become similar to a delusion that has become widespread. I increasingly hear the thesis that it is necessary to distinguish between the terms of the contract and a copy of the contract , for example. At the same time, the authors of these theses could not explain to me how these terms differ. They hinted that the two terms indicate completely different objects, but in what paradigm the terms contract copy and contract point to different objects, I was not told. I consider this a very serious error and I will try to explain the reasons for its occurrence.

In the logic of Aristotle, from which we borrowed the word instance, the terms fish and fish instance are the designations of the same object. At the same time, I deliberately do not say that an instance is a term. The word copy in the logic of Aristotle is inseparable from the second word, forming together with it an indivisible term. However, outside the logic of Aristotle, the terms fish and fish specimen , pointing to us at the same object (fish), however, differ from each other. The question is what?

We need to find out how they differ, and whence the thought came to mind that these terms differ in something else. To understand this, I was motivated by the task of describing the simulation modeling of business systems. About what terminological difficulties I encountered, and how I had to overcome them - you can only tell in a separate book. Now I will focus on only one question: what is an object and what is an object instance?

Let there be a saying: “I am holding a copy of the book The Three Musketeers.” It is interpreted as follows:

- There is a type of books "Three Musketeers", and there is a specific copy of this type of objects - a specific book. The word instance gives us a strict reference to the context we use. The context is Aristotle's logic, or philologists use the term intensional context.

However, this statement may be abbreviated to the following: “I am holding the book The Three Musketeers.” This statement can be interpreted in two ways:

- We can say that the object that I hold in my hands has a property. This property of an object is to be a book called The Three Musketeers (Aristotle's Logic, or Intentional Context). This interpretation coincides with the interpretation, which generates the term copy of the book.

- And we can say that we have before us the object (element) of the class book "Three Musketeers". Such a statement suggests that we are within the framework of the logical paradigm or, as philologists say, in extensional context.

Conclusion: The term OBJECT OF THE OBJECT indicates to us the intensional context explicitly, and the term OBJECT assumes that we are free to choose the context (intensional, or extensional).

One object, or many?

Let us return to the question that there are different pieces of paper with an inscription contract? The answers, as we have seen, may be:

- these are two different contracts

- This is one contract, but its copies are different.

If the analyst insists on a second interpretation, I ask the question: where, in which paradigm do objects and their instances exist? The analyst cannot answer this question, since such a paradigm does not exist. However, in some books there is a confusion in terms, thanks to which such an expression was born and actively spread.

I have to conduct a digression into history and explain to the analyst that the term instance is associated with the term type. And that the term copy of the book has the following interpretation: there is a type of books, and there is a specific copy of this type of books - a specific book. And there is no such interpretation: there is an object book, and there is a copy of it.

Let me remind you: we remember that the type of Aristotle is a set of parameters. The instance is the value of these parameters.

After the analyst decides to continue the study, we continue to move with him, relying now only on logic.

We can also assume that there are two terms at the same time: a copy of the contract of sale and a copy of the contract of sale of June 30th. It is clear that the same piece of paper can be a copy of the contract of sale and a copy of the contract of June 30th. This means that we have allowed the existence of two types, which may include one object of the real world! But this paradox was one of those that eventually led to the emergence of the theory of sets. The Aristotelian model could not answer the multiplicity of types.

Another example of reasoning

One can reformulate the question in the following way: what parameters does the type of contract to which the analyst refers to, using the term contract copy? Then I use the following survey script:

Next, I ask the second question: what parameters does the type of contract, which the analyst mentioned, has, offering a choice:

If the analyst gives the first answer, then I ask the question: does he admit the existence of this type of contract, which includes all copies of all contracts of sale? If so, how do we distinguish in conversation, what type are we talking about? And it turns out that the same copy can relate to two different types of contracts? But this is a modernization of Aristotelian logic, about which we know nothing. It turns out that the object can be both a machine and a ship. Aristotle's logic could not give an answer to this, and therefore we had to invent the theory of sets.

If the analyst answers the second way, I ask the second question: Does the mentioned type contain the parameter “Whose copy?” There can be two answers:

If I get the first answer, then I ask the question: what is the type, a copy of which is a copy of the contract of June 30?

If I get a second answer, then I clarify, and what are the objects that contain this parameter? You heard the answer: there is one object, and there are many instances of it, which brings us back to the question of the logic and correctness of such a thesis.

Next, I ask the second question: what parameters does the type of contract, which the analyst mentioned, has, offering a choice:

- The first type applies only to those objects that have recorded information about a specific agreement. It contains the parameter “Whose copy?” (Contractor, customer). An example of the use of this type: a copy of the contract of April 30th.

- The second contains the parameters: the date of signing, the subject of the agreement, legal entities, and so on. An example of the use of this type: a copy of the contract of sale.

If the analyst gives the first answer, then I ask the question: does he admit the existence of this type of contract, which includes all copies of all contracts of sale? If so, how do we distinguish in conversation, what type are we talking about? And it turns out that the same copy can relate to two different types of contracts? But this is a modernization of Aristotelian logic, about which we know nothing. It turns out that the object can be both a machine and a ship. Aristotle's logic could not give an answer to this, and therefore we had to invent the theory of sets.

If the analyst answers the second way, I ask the second question: Does the mentioned type contain the parameter “Whose copy?” There can be two answers:

- Yes, contains

- No, it does not. This is the most common answer, since in all workflow and accounting systems it is this type that is actively supported.

If I get the first answer, then I ask the question: what is the type, a copy of which is a copy of the contract of June 30?

If I get a second answer, then I clarify, and what are the objects that contain this parameter? You heard the answer: there is one object, and there are many instances of it, which brings us back to the question of the logic and correctness of such a thesis.

An example of the representation of the domain model

Let's take a look at how analysts typically model standard subject areas. For example, such:

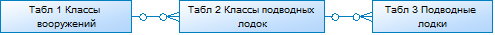

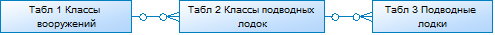

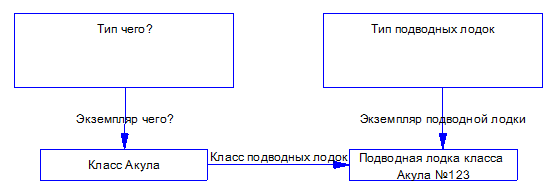

We see that all the many weapons are divided into classes. Each class of weapons, in turn, is divided into subclasses. We see that the class of submarines is a subset of the class of armaments, and the class Shark is a subset of the class of submarines.

A frequently occurring implementation of this model in the form of tables is as follows:

Table 1 models the weapon class subclasses. Table 2 - submarine class subclasses. The relationship between table 1 and table 2 models weapons specialization. Table 1 models the submarines, and the relationship between Table 2 and Table 1 models the classification of the submarines. (The terms specialization and classification are taken from a logical paradigm and are not random.) It is clear that one subclass of weapons "submarine" corresponds to many subclasses of the class of submarines and it is clear that one subclass of submarines may belong to many submarines, which is indicated by the "Crow's foot" at the end of the relationship between the tables. It is considered that the structure of the tables is the domain model, but, as you can see, there is much less information in the structure of the tables than in the domain model.

This model is very similar to others like it:

The domain model in the paradigm of Aristotle

Recalling what I said in the article that in Aristotelian logic a table is a description of the type of objects, and an entry in the table is a description of an object, let us draw a domain model in the paradigm of types and instances. (In this paradigm, the most frequent discussion is the subject area and the naming of tables). For this, we apply the formal approach, which I voiced in the article. That is, the table - indicates the type of objects, and records in it - instances.

The resulting model looks like this:

Table 3 simulates the type of submarines. An entry in the table simulates a submarine instance. The link to the entry in table 2 models the fact that the submarine belongs to a certain class of submarines. But with table 2 we can not decide. What kind of objects does this table model? An instance of which is an entry in this table? There are no terms in the Aristotelian logic for these entities. We can try to invent the name itself for the type of objects that are stored in table 2, for example: the type of classes. Then the Shark Class will be an instance of the class. (I will note that an instance of a class points to a class, and not to a class object, as some might think. A CLASS ELEMENT, not a CLASS INSTRUMENT indicates a class object!). The resulting model now looks like this:

The problem is that at the same time in the same model we see both object types and classes. (I sometimes met the tables entitled: types of classes, types of types, types of classes, and so on ...) One should understand that types exist only in Aristotelian logic, and classes exist only in logical ones. And they do not mix. Therefore, we should rename the class Shark to the submarine type Shark. The rhetoric would be this: along with a copy of the submarine we have a copy of the Shark, where by the Shark is meant the type of submarines. However, in this article I propose to stop and see what will happen to other models - dogs and welds.

The limitations of the paradigm of Aristotle

In the case of dogs, table 2 - there is a description of the type of breeds. And in the case of seams - type types. And here the ambush arose. Imagine: at a meeting of analysts, we discuss the structure of the tables and we have the following terms: type of types. Few people will understand this. It is too difficult for everyday speech and everyday understanding. Personally, if I have met such a term, it is extremely rare. The problem is that Aristotle did not work the terminology for describing structures more difficult than classes, for example, a class of classes. Set theory did this much later. But our analysts do not yet know about the existence of the theory of sets and are trying to get out of the framework of Aristotelian logic. To do this, they change the rhetoric. New rhetoric was borrowed from the description of information objects. In the description of information objects, long before the problem arose with the types of the types, a “solution” was found. The “solution” arose by itself, since no one thought about it.

Formulation of the problem

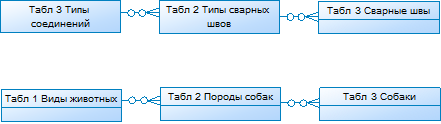

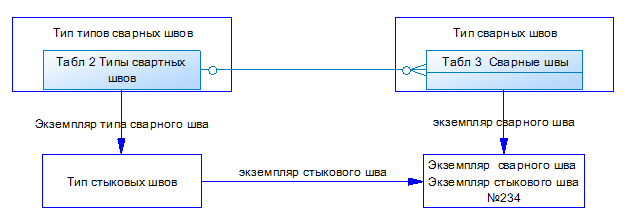

Let's see what it looks like when applied to welds. At first there was such a structure of tables describing such a domain model:

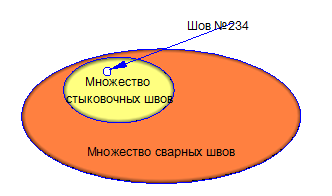

In such a model, weld No. 234 can be called in two ways: a copy of the weld and a copy of the butt weld. Both of these terms are correct terms, and it is convenient to explain them within the framework of set theory. It is clear that weld No. 234 belongs to the class of welds. It is clear that weld No. 234 also belongs to the class of butt welds, which is a subclass of welds:

In the data structure, this is reflected as follows: the entry in the table “welds” tells us about the first classification of the object, and the connection with the entry in the table “types of welds” tells us about the second classification.

I note that two different forms of modeling the same “classification” connection, which is between the seam and the class of welds and between the seam and the joining classes, tells us that the modeling with the help of tables was not created for the correct modeling of the subject area.

But to explain that the type of butt seams is an instance of types of welds, it becomes already awkward.

"Decision"

To get rid of such intricate terms, sometimes they paint the following structure:

Now we have everything in conversation. You can check.

The design at first glance seems reasonable, but exactly until we draw a model of terms:

Now we have a few surprises:

- The entry “Butt Seam” models (surprise!) No, not a seam! It simulates a whole class of stitches!

- The table WELDED JOINTS contains (surprise!) No information about welds, no! It contains information about the class of welds!

- TYPE of welds has no relation to the type of welds.

- The weld specimen is not a copy of the weld.

- BUTT of the butt weld - not a copy of the butt weld.

- Up to this point, the two terms “Instance of the weld” and “weld” indicated one object — a weld. However, now I sometimes hear from some analysts that it is necessary to distinguish between a weld and an instance of a weld, as if they were two different things!

This design is self-made and erroneous. The reason is that it does not rely on any of the ontologies and is a substitution of concepts. As I have already said, in the Aristotle paradigm, the terms an instance of a butt weld and a butt weld indicate the same real-world object — a particular butt weld. In the drawn structure, the object of the Buttress seam does not indicate an object, but a class of objects!

As a result, a number of analysts begin to think in a distorted way: they no longer distinguish between different objects, calling them one term: Butt joint. Their rhetoric is the following: there is one object “Butt Weld” and there are various of its COPIES. They have in mind one athlete and many of his COPIES! It should be understood that by the term INSTANCE these analysts understand something that Aristotle did not know, or anyone else. This is a self-made term that looks terrible from any point of view: from logical and linguistic points of view. That is, the INSTRUCTION of the butt joint for them means: there is an object BUTTON SEAM and there are its INSTRUMENTS. Well, that Aristotle does not hear this!

Another example of a similar "Solution"

Now we give an example of this kind of modeling, which we find everywhere. Take our favorite contract. In any system we will find the following directory:

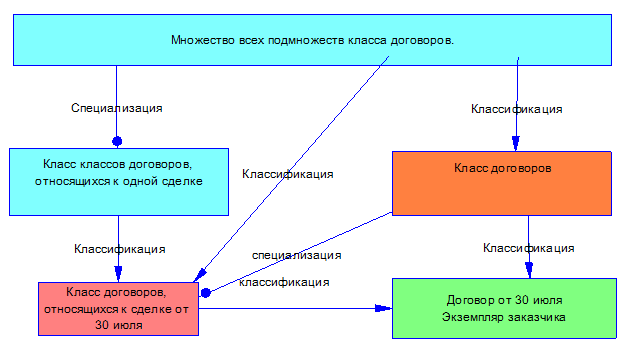

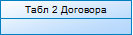

Each entry in this directory models ... And what does it model? The name suggests that the entry in this directory is either a contract or a model contract. The record in the database does not contain the signatures of the parties, can not be a contract. Therefore, information about contracts is stored here, that is, information about other information objects. We know that one record in the database corresponds to the set of copies of the contract dated June 30th, differing by whether they belong to the Customer or the Contractor. Let's try to draw a model of terms:

We see the same picture, which was analyzed earlier. This is where the concepts of object and its copy came to us! From incorrect modeling of information objects! We see in this model different copies of the same contract. What was required to show. Only in an incorrect model incorrect terms can be born: an object and its instance.

The reason for this kind of delusions lies in the ignorance of logic and in the misunderstanding of the essence of information objects.

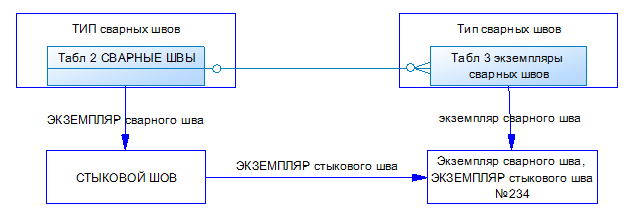

Correct solution

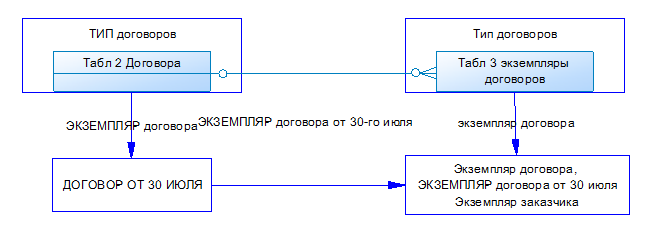

Let's apply the correct approach to modeling contracts and see how the data structure should look in a consistent way from the point of view of Aristotelian logic (not counting types of types and the presence of a plurality of types).

So, it turns out that the database in the Contract table contained information about the type of contracts, not about the contract! Note that there is a strong opinion that we store information about the information object, and not about the set of information objects! The directories we work with every day are called: Contracts, Invoices, Invoices, and so on. And not the types of contracts, types of invoices and types of invoices.This led to a massive misconception, which is now manifested in the conviction of many analysts that there is an object and there is an instance of it. Remember, business process modeling standards! This fallacy has penetrated into the standards!

But what then is the reference book in which information about contracts is stored (in Table 3, if we follow the notation in our practice)? I have seen many names, among which are: Signed agreements (as if there are not signed), Copies of agreements (as if there is an object and its copies), Agreements sent out, Formed agreements, Completed agreements, Printed agreements. Everyone who is faced with the need to account for real information objects, comes up with their own names.

Finally, we came to the answer to the question asked earlier: are different pieces of paper with seals and signatures different objects, or are they different instances? The answer is obvious - these are different objects! We see that the existing practice of naming tables does not hold water. Now that we have figured out that each document we have is a separate document, we have to build the correct model of these objects. To understand how to do this without distorting the language (giving rise to species, types, classes, genus, etc.), we will have to turn to set theory.

Solution in a logical paradigm

In set theory, there are three classes of objects: objects, classes and classes of classes, as well as classes of relations between objects and classes. I will not list all possible constructions, but I will give explanations as necessary.

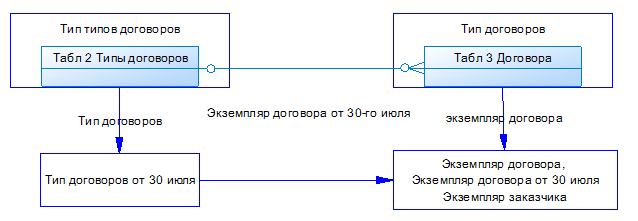

Suppose we have a set of all contracts (in the sense of each piece of paper - a separate contract). Each contract belongs to a class of contracts.

Then they say that the contract is associated with the class of contracts relationship classification.

The class of sales contracts is a subset of all contracts.

The relationship between the class of all contracts and the class of contracts of sale is called specialization.

The class of contracts of sale, the class of the lease and so on. - there are objects of the set, which is the set of all subsets of the contract class.

The set of all subsets of the class of contracts is a class of classes, and it connects it with the class of all contracts, the class of sales contracts, the connection classification.

Among all the subsets of the set of contracts can be identified those subsets that relate to a single transaction. Combining these subsets into one class, let's call it subclasses of the contract class. That is, the contracts of one class represent the model of one object - one transaction.

Now we are ready to draw the structure of the tables and give them names.

The domain model in the logical paradigm looks like this:

And the structure of the tables that implements this model is:

How will it sound in practice?

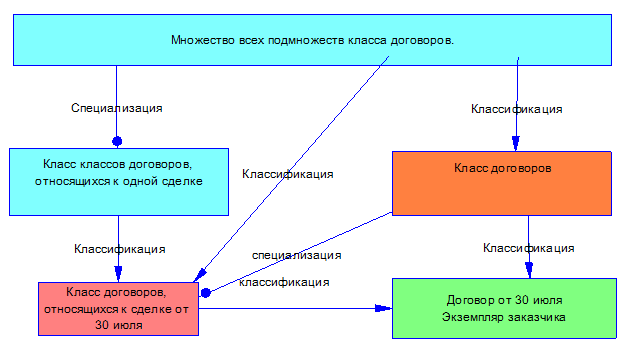

- Table 3 models the contract class and contains contract models.

- Table 2 simulates the class of classes of contracts relating to a single transaction, and contains models of classes of contracts relating to a single transaction.

- The relationship between table entries models the relationship classification between classes of contracts relating to a single transaction and contracts.

I note that the diagrams of relations between the entities of the domain in the logical paradigm are drawn simply, uniquely and demonstrate completeness. Their meaning is easy to read, if you remember and know the meaning of the names and symbols. These models demonstrate completeness in contrast to domain models made in the form of ER – models. To simulate the same information, you can build different ER-models. This is clearly seen when there is a domain model in the logical paradigm. It becomes obvious arbitrariness of the choice of tables for storing information about the subject area.

To complete the conversation about information objects and their modeling, I propose to pay attention to the “blurring” of information about the object of the domain in terms of the data structure. This gives us reason to say that there is no unambiguous correspondence between the objects of the domain and the objects in the system. Moreover, often one record in a table stores data about an object and a class of objects at the same time! All this is deprived of a logical data model. Therefore, it is sometimes called a data model in the latter normal form.

Another affected subject area

, . , , . , - . , . , . …

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/246017/

All Articles