Peter Thiel: How to build a monopoly?

Stanford course CS183B: How to start a startup . Started in 2012 under the leadership of Peter Thiel. In the fall of 2014, a new series of lectures by leading entrepreneurs and Y Combinator experts took place:

Second part of the course

First part of the course

- Sam Altman and Dustin Moskovitz: How and why to create a startup?

- Sam Altman: How to form a start-up team and culture?

- Paul Graham: Illogical startup ;

- Adora Cheung: Product and Honesty Curve ;

- Adora Cheung: The rapid growth of a startup ;

- Peter Thiel: Competition - the lot of losers ;

- Peter Thiel: How to build a monopoly?

- Alex Schulz: An introduction to growth hacking [ 1 , 2 , 3 ];

- Kevin Hale: Subtleties in working with user experience [ 1 , 2 ];

- Stanley Tang and Walker Williams: Start small ;

- Justin Kahn: How to work with specialized media?

- Andressen, Conway and Conrad: What an investor needs ;

- Andressen, Conway and Conrad: Seed investment ;

- Andressen, Conway and Conrad: How to work with an investor ;

- Brian Cesky and Alfred Lin: What is the secret of company culture?

- Ben Silberman and the Collison Brothers: Nontrivial aspects of teamwork [ 1 , 2 ];

- Aaron Levy: Developing B2B Products ;

- Reed Hoffman: On Leadership and Managers ;

- Reed Hoffman: On the leaders and their qualities ;

- Keith Rabois: Project Management ;

- Keith Rabua: Startup Development ;

- Ben Horowitz: Dismissal, promotion and reassignment ;

- Ben Horowitz: Career advice, westing and options ;

- Emmett Shire: How to conduct interviews with users;

- Emmett Shire: How to talk to users in Twitch ;

- Hossein Rahman: How hardware products are designed in Jawbone;

- Hossein Rahman: The Design Process at Jawbone.

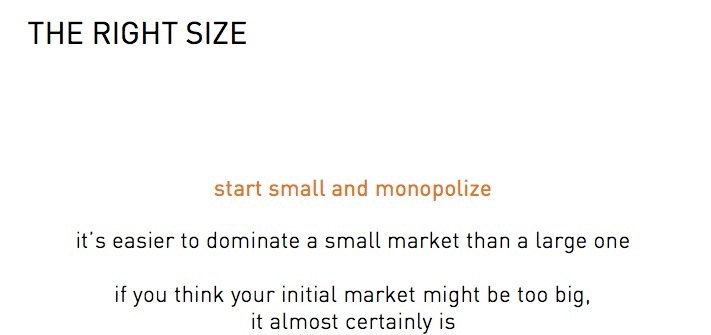

I want to tell you something about how monopolies are created. I think one of the ideas that are extremely illogical at first glance that are associated with monopolies is that you need to look for small markets. If you work in a startup, you want to eventually come to a monopoly. If you create a new company, you want to become a monopoly as a result. Monopolies occupy an overwhelming market share - so how do you get it? You start from a small market and eventually occupy it entirely, and after a while you get the opportunity to expand the existing market like divergent concentric circles.

')

From the first day, targeting a huge market is a big mistake, because it is usually evidence that for one reason or another you have not segmented it clearly enough, which means that in one way or another you will come across too active competition. It seems to me that almost all successful companies in Silicon Valley adhered to the model of entering small markets and subsequent expansion.

Take Amazon, they started selling books, but they said that they had the best bookstore in the world, and in 1990, when they started a business, it was. They sold books online, and you, as a customer, could do what you previously couldn’t use - so Amazon has gradually grown to all possible forms of e-commerce and other things that go beyond its borders.

Take Ebay - they started with the sale of mechanical dispenser toys with Pez candies, then switched to Beanie Babies, and eventually they came to an online auction system for all sorts of goods. It is illogical with respect to all these companies that they started with markets so small that when their business was created, people did not consider these companies as valuable as they were.

An example of this development from PayPal

We started working with regular sellers on Ebay - there were about 20 thousand in total. When, after launching in December 1999 - January 2000, we saw interest on their part, it seemed to us that this was the end: the market is small, the customers are terrible - these are people who sell some kind of nonsense via the Internet, which we should try to work with this market?

But we had a chance to give them a product that, in the eyes of this audience, exceeded the capabilities of all our competitors, so we took about 25-30% of the market in the first two or three months of work - with this you could start building a business, relying on brand awareness . So it seems to me that these small markets are undervalued.

But we had a chance to give them a product that, in the eyes of this audience, exceeded the capabilities of all our competitors, so we took about 25-30% of the market in the first two or three months of work - with this you could start building a business, relying on brand awareness . So it seems to me that these small markets are undervalued.

Facebook went the same way: I often repeat that if the initial market for Facebook was 10,000 Harvard students, the company's share in this market took off from zero to 60% in ten days - an impressive start. In business schools you are often told: this is a tiny market, it's just ridiculous, there is no value in it.

So if they analyzed examples of Facebook, Ebay or PayPal, they would conclude that all these companies started from markets so small that they had no value, and if these markets were so tiny, then no value to companies. in the future they would not have brought - but it turned out that there is a possibility of concentrically increasing the potential of these markets, which greatly increased the value of companies.

The opposite option - work in the super-large market. Over the past ten years, a lot of trouble has occurred with clean tech companies, but the vast majority of their problems began with the fact that they initially aimed at huge markets. Each PowerPoint presentation from such a company in 2005–2008 (it was a kind of clean tech bubble in Silicon Valley) began with a description of the energy market, which was measured in hundreds of billions and trillions of dollars. And when you are a small fish in the vast ocean, this does not bode well for you. This means that you have thousands of competitors, and you do not even know who they are.

Therefore, it is much better to be a one-of-a-kind company within a small ecosystem. No need to become the fourth pet food company. Or the tenth company to create solar panels. Or the 100th restaurant in Palo Alto. The restaurant industry is estimated at trillions of dollars. And if you analyze the market volumes, then decide that restaurants are a fantastically profitable industry.

Very often, large markets are also many competitors. They are very, very difficult to segment. Therefore, the first illogical idea is to look for small markets, such that people may not even notice them, not think that they have a meaning. This is your starting point, and if these markets are able to expand, you can become a monopoly.

So, now let's move on to the second of a number of characteristics of monopoly businesses that I would like to dwell on. There is probably no universal recipe for achieving monopoly. But there is a feeling that in the history of the development of technology, no bright moment repeats twice. Therefore, the next Mark Zuckerberg will not create a social network, the next Larry Page will not make the search engine, and the next Bill Gates will not develop an operating system. If you copy these people, you don’t learn anything from them.

Only unique businesses that create something they have never had before have the potential to create monopolies. “Anna Karenina” begins with the words that “all happy families are alike, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way” - in business the opposite is true: all happy companies are different from each other, because each of them does something unique. And all unhappy companies are similar, therefore they cannot avoid similarity to each other in key issues, which leads to the appearance of competition.

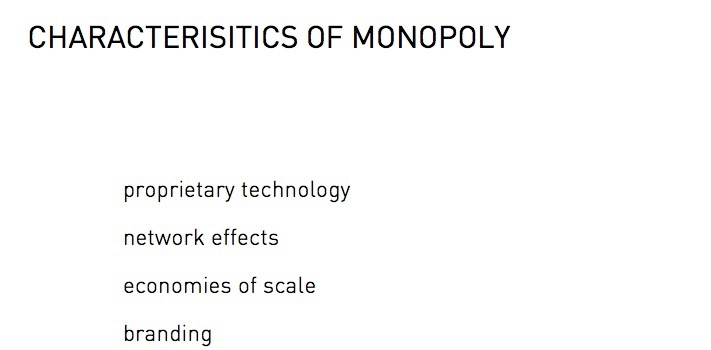

One of the characteristics of a monopolistic technology company is the possession of a kind of "own" technology. My insane, a kind of arbitrarily established practical principle is that you need a technology that exceeds the coming “new [technological] hit” by an order of magnitude. Take Amazon: they had ten times more books [than competitors] - they may not have created a product at the height of technology, but they found a way to effectively sell ten times more books online.

In the case of purchases on Ebay, an alternative to PayPal was to send a check that took a week, while using PayPal it was possible to pay more than ten times faster. You need to greatly improve any key element of the business, improve it by an order of magnitude. And of course, you can offer the market something radically new - it will be a kind of limitless improvement. I would call the iPhone the first truly working smartphone - limitless or not, but it was an improvement on the order. Technologies should be developed to give you the opportunity to far surpass the new "hit" designs of competitors.

It seems to me that the network effect can often move the process forward - therefore it is [also] very useful. From time to time it may contribute to the creation of monopolies, but the trick is that it is very difficult to achieve. And although everyone understands how important this effect is, there is always an incredibly difficult question: how can the network help the first person to start using it? [Another] typical example of a monopoly business is a business in which economies of scale are possible when your fixed costs are very high and your marginal costs are very small.

And, moreover, [one of the characteristics of monopolies is] branding - an idea that is firmly entrenched in the minds of many. I have never fully understood how branding works, so I have never invested in companies in which everything is built entirely on it, but nevertheless, this, in my opinion, is a real phenomenon that creates real value.

I think (before the end of the lecture, I’ll come back to this thought) that one of the reasons why businesses based on software “shoot out” so often is because they have many of the [above-mentioned] characteristics. They easily save on scale, because marginal costs for software are zero. And if you get a working product from the software industry, which turns out to be noticeably better than existing solutions, the economy of scale is activated, and you can scale your business very quickly.

Even if your market is initially relatively small, you can grow your business fast enough to occupy the same share as the market itself grows and establish monopoly power on it. Monopoly is not enough to remain so in the short term. It is important to create a monopoly that persists for a long time.

In Silicon Valley, it is widely believed that you should be a pioneer in the market, but it always seemed to me that in some cases it would be much better to be the last to enter the market. You need to be one of the last companies in the selected category, those who really have value. Microsoft created the latest operating system - for decades no one could do anything better. Google has become the latest search engine. Facebook will have value if it turns out that nothing more worthwhile has been created after this social network.

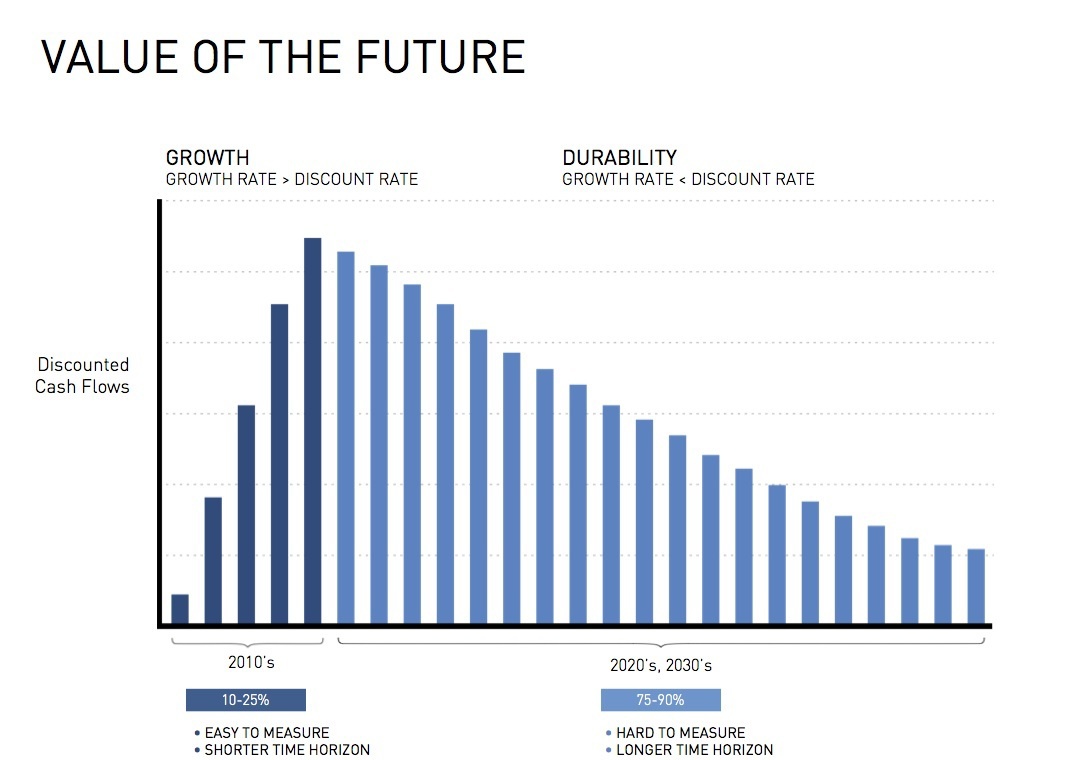

One way to appreciate the significance of this last player is to treat its value as something that manifests itself in the distant future. If you calculate discounted cash flow for such a business, evaluate all inflows and calculate its growth rates, it turns out that growth rates are much higher than the discount rate, which means that the main value of the company can be obtained only in the future.

I spent these calculations for PayPal in March of 2001 - at that time we worked in the market for about 27 months and grew by 100% per year. We discounted future cash flows at a rate of 30%, and it turned out that about three-quarters of the value that our business will generate will be provided by the cash flows that we will receive in 2011 and later.

Which of these [above-mentioned] technology companies you would analyze, the results will be about the same. So if you try to do an analysis on one of the IT companies from Silicon Valley, for example, AirBnB, Twitter, Facebook, on any of the growing Internet companies, or companies from YCombinator, mathematical calculations will show that three-quarters of these companies are 85% values will be provided with cash flows for the years 2024 and later.

This is a very long time, and it shows that in the Valley we value growth rates too high and underestimate the companies' survivability rates.

Growth is something that you can measure here and now, you can track this indicator very accurately. The question is whether the company will exist in ten years - it is he who prevails in assessing the value of companies, and is rather related to quality indicators.

Returning to the characteristics of monopolies: "own" technology, network effect, economy of scale - all these characteristics really exist at the moment when you assess the state of the market, but you need to think about whether these qualities will continue in the future. Therefore, an indicator of time is added to all these characteristics. The network effect, by the way, is very dependent on time - as it scales, it gets stronger. Therefore, if your business is built on the formation of a network, then over time your monopoly will only become larger and more powerful.

"Own" technology is not an easy thing. You need something an order of magnitude surpassing those achievements that are currently elevated to the rank of "works of art." So you will attract the attention of the audience, so you can get ahead. But you do not want anyone else to push you out of the market. There were enough spheres in the world in which the active development of innovations took place, but none of them as a result paid off.

For example, the production of disk drives in the 1980s: you could create the best disk drive in the world, you could become a monopolist in the world market, but in a couple of years you could easily be pressed by some competitor. For fifteen years, disk drive technology has improved markedly, it has brought huge benefits to consumers, but has not helped the creators of companies.

It is not enough to create a breakthrough technology in any industry, then it is necessary to substantiate why your breakthrough will be the last, or at least why you will not be replaced by competitors in the coming years. Or you need to figure out how, by creating a breakthrough technology, you can constantly improve it so that other market players cannot get close to you. If there are many other innovative solutions on the market in addition to the product you are working on, and your competitors are creating alternative products, such a plan is very good for society as a whole, but as a rule, it promises little good for you personally.

And now about the economy of scale. It seems to me that in this respect it is very important to be the last to enter the market. It is difficult for me to refrain from not overdoing analogies with chess: White makes the first step in chess, so White has a slight advantage of the first move. You, on the other hand, want to be the one who makes the last move and wins the game - remember the statement of world chess champion Capablanca: "You must start by studying the end of the game." I would not say that this is the only thing you need to learn, but I believe that it is critically important for you to try to think up answers to questions about why your company will remain a leader in ten, fifteen, twenty years.

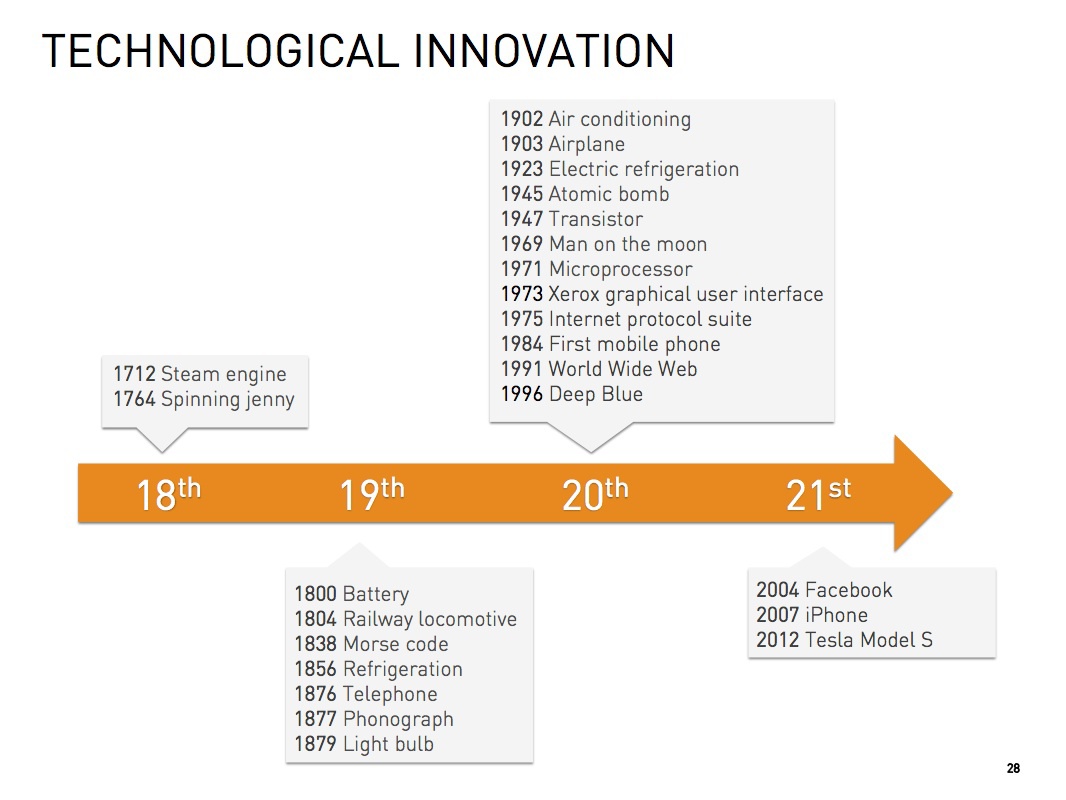

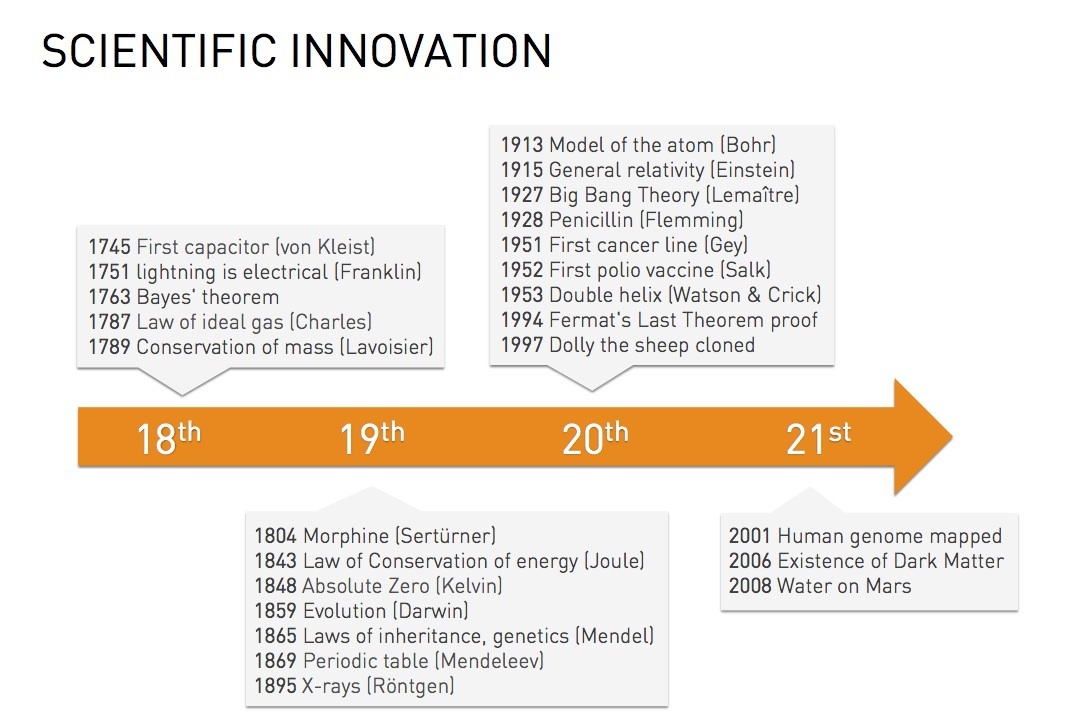

I want to consider two other areas of the idea of opposing monopoly and competition. This confrontation is the essence of my understanding of business, how to create it, how to evaluate it. It seems to me that this approach allows you to look at the entire history of innovations in technology and science from an unusual angle. We have experienced almost 300 years of incredible technological progress in a variety of industries. From steam engines to railways, telephones, refrigerators and home appliances, the computer revolution, airplanes - technological innovations in all areas of activity. About the same can be said about science - for hundreds of years incredible discoveries have occurred in science.

It seems to me, thinking about this, many overlook the fact that since X and Y [reasoning about X and Y variables are in Part 1 ] are independent variables, some of these innovations can be incredibly valuable, but those who have thought of them, may not receive rewards for them. So back to the beginning [lecture]: you need to increase the value of the company to X dollars, of which you get Y percent from X. It seems to me that in the history of science, Y value almost always was zero, scientists never earned anything [on the results of their work ]. They are constantly deceived by the idea that they live in a world that will reward them for their work and inventions. This is probably a fundamental misconception, because of which scientists in our society have to suffer.

Even in the technology industry, there are many different areas in which outstanding innovations were created that provided an invaluable service to society, but did not bring any value to their creators. The whole history of science and technology can be presented in terms of how much value a given discovery could give. Certainly, in this industry there are entire sectors, the work in which did not give scientists anything at all.

You can be the smartest physicist of the twentieth century, create a general and special theory of relativity, and not become not only a billionaire, but even a millionaire. Such an approach [in science] for some reason simply does not work. The railways had an incredible value, but the railway companies went bankrupt due to excessive competition. The Wright brothers, who made the first flight on an airplane, did not earn anything. It seems to me that an understanding of the structure of these industries is extremely important with regard to this issue.

Take a closer look at this gap in the last 250 years.

Practically none of the scientists in this period earned anything, either in the field of science or in the field of technology. Very few managed to make a profit from their work. At the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century, the first industrial revolution in weaving mills took place, steam engines and production automation appeared. Technology is constantly improving - the efficiency of textile factories and production as a whole grows by 5-7% annually, year after year, decade after decade.

All 70 years from 1780 to 1850 there is a continuous improvement in production. But even in the 1850s most of the capital in the UK belongs to the aristocracy, and the workers practically do not earn. The capitalists, oddly enough, at that time also received relatively little, almost all the funds went into competition. Weaving factories were run by hundreds of people, and in this industry the structure of competition did not allow people to earn.

In the entire history of the last 250 years, in my opinion, there were only two big directions in which people created innovations and took profits from them. One of them is a kind of vertically integrated complex monopolies, within which the second industrial revolution of the late XIX - early XX century was realized. These are companies like the Ford concern.

There were vertically integrated oil companies, such as Standard Oil, and all these vertically integrated monopolies needed very difficult coordination, many elements had to be adjusted to each other, but if you succeeded, you would get an incredible competitive advantage. Now this is practically not happening, but it seems to me that this format of business has great value - if, of course, the company’s management is able to implement it. This format is also extremely expensive.

All 70 years from 1780 to 1850 there is a continuous improvement in production. But even in the 1850s most of the capital in the UK belongs to the aristocracy, and the workers practically do not earn. The capitalists, oddly enough, at that time also received relatively little, almost all the funds went into competition. Weaving factories were run by hundreds of people, and in this industry the structure of competition did not allow people to earn.

In the entire history of the last 250 years, in my opinion, there were only two big directions in which people created innovations and took profits from them. One of them is a kind of vertically integrated complex monopolies, within which the second industrial revolution of the late XIX - early XX century was realized. These are companies like the Ford concern.

There were vertically integrated oil companies, such as Standard Oil, and all these vertically integrated monopolies needed very difficult coordination, many elements had to be adjusted to each other, but if you succeeded, you would get an incredible competitive advantage. Now this is practically not happening, but it seems to me that this format of business has great value - if, of course, the company’s management is able to implement it. This format is also extremely expensive.

Our modern culture forms people who are very difficult to get involved in complex tasks, the implementation of which also requires a lot of time. When I think about my colleague and friend Elon [Mask] - from PayPal achievements to Tesla and SpaceX, it seems to me that the key to the success of these companies was to create a complex vertically integrated monopoly structure.

Take a look at Tesla or SpaceX: is [the success] of these companies the result of a single [technological] breakthrough? These companies developed innovations in several industries at once, and I do not think that their success is due, say, to a single achievement in a tenfold increase in battery power. They can work there, for example, on rocket engineering, but this is not about a single innovative breakthrough. What really impresses is how all these processes are integrated there, as well as how they are included in the overall vertical structure, which most competitors do not have.

Tesla has integrated car distributors into its business - they are ready to share their success, which is not done by the rest of the US car market. And SpaceX, for example, includes all subcontractors, while most other aerospace companies use the services of subcontractors from a single structure that receives monopoly profits and does not allow aerospace companies to earn money themselves. Therefore, vertical integration, in my opinion, is a characteristic of technological progress, which has not yet been fully studied, and to which one should definitely take a closer look.

[The second in the last 250 years is the direction in which the creators of innovations have the opportunity to extract profits from them - software]. It seems to me that the very essence of software has a very powerful potential [to the formation of monopolies]. The software allows you to save on the scale, the marginal costs in the process of its creation are extremely small, and even the world of zeroes and ones can be opposed to the world of atoms — in the world of bits, the adoption of new technologies is very fast.

Rapid adoption of the innovation is crucial for entering the market and capturing it, because low adoption rate of your product even in a small market will allow others to take advantage of time and enter the same market with competing products. And if, on the other hand, your market is small or medium, and you have a fast rate of acceptance of your product by the audience, it means that you can become a leader in this market. That is why, in my opinion, Silicon Valley has become a shelter for profitable companies, and software development as a whole is such a phenomenally successful industry.

I would like you to remember the various explanations that people use when trying to find an answer to the question of why some things work and others don’t. I think that these explanations become extremely vague when it comes to creating a company with a value of X dollars and getting yourself Y percent of X.

The scientific explanation [of why representatives of science rarely manage to commercialize their own invention or discovery], which we are constantly being told about, is that scientists are not interested in making a profit. They work “for the benefit of everyone”, so if money is important to you, you are a bad scientist. I do not want to say that people should always motivate money, but it seems to me that we should be more critical of such explanations. We need to ask the question, is this explanation an attempt to hide the fact that Y is zero, and scientists work in a world where all innovations are “burned” under the pressure of competition, and it is not possible to use their fruits?

, , , , , , – . Twitter , Twitter, , , .

«» , X Y – , , X , , . , – , : - , «» , - , .

. . , , – . , , , – , . – , , , , , . , , , , : .

, . , – , . .

, « » , « » – , , , , . «» , [. «»] – - , , , , , .

[ ] – , . « ». , , – . , , – . - , .

– , - , . , - . [ , ] , , – . : ?

? , : « , » – , , .

, , ? : , , , . , .

«». : « , ». , -: , «» , , , «», – , , , -, – , 7 3 .

, : , – , , - . «» , , .

, : , – , , - . «» , , .

, , , , . , , , , , . , , : , - . , – , , . Thank you very much for your attention!

[ :]

?

: , : ? « » – , – « - ». – , .

, -, Google?

: , -, , , «» , – -, . , , Google . , , , , , .

Do such characteristics apply to Palantir and, secondly, [what do you think of] Square?

: , . Square, PayPal – – , – , . – – Palantir, , . , : , – , , Palantir. .

What do you think about the concept of "Lean Startup"?

: , , «» , , .

« ». , - , . , , : , – , – [, ], - , , , -, . , , , [ ], .

, – , . , , , , , . , -, . , , , , , , , , . , . , – .

« ». , - , . , , : , – , – [, ], - , , , -, . , , , [ ], .

, – , . , , , , , . , -, . , , , , , , , , . , . , – .

Does the fact that the company enters the market last does not confirm the fact that the company has to compete?

: , . , , . , . , Google . , . , . Facebook .

, 1997- Social Net – « » 7 Facebook. , , - – , . Facebook , , , Facebook . , , , .

, 1997- Social Net – « » 7 Facebook. , , - – , . Facebook , , , Facebook . , , , .

If someone has worked for six months at Goldman Sachs, enrolled at Stanford, how can he overestimate his competitive advantages?

: , , , . , , - – , «-» , – , , . , – . 1999 , - « ».

, . 2005-2007 , . . , , , - . , , , .

( ) . , – , [ ]. , , , . , , , , – – , .

, . 2005-2007 , . . , , , - . , , , .

( ) . , – , [ ]. , , , . , , , , – – , .

[ Translation of the next lecture by Alex Schulz ]

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/245525/

All Articles