Peter Thiel: Competition - the lot of losers

Stanford course CS183B: How to start a startup . Started in 2012 under the leadership of Peter Thiel. In the fall of 2014, a new series of lectures by leading entrepreneurs and Y Combinator experts took place:

Second part of the course

First part of the course

- Sam Altman and Dustin Moskovitz: How and why to create a startup?

- Sam Altman: How to form a start-up team and culture?

- Paul Graham: Illogical startup ;

- Adora Cheung: Product and Honesty Curve ;

- Adora Cheung: The rapid growth of a startup ;

- Peter Thiel: Competition - the lot of losers ;

- Peter Thiel: How to build a monopoly?

- Alex Schulz: An introduction to growth hacking [ 1 , 2 , 3 ];

- Kevin Hale: Subtleties in working with user experience [ 1 , 2 ];

- Stanley Tang and Walker Williams: Start small ;

- Justin Kahn: How to work with specialized media?

- Andressen, Conway and Conrad: What an investor needs ;

- Andressen, Conway and Conrad: Seed investment ;

- Andressen, Conway and Conrad: How to work with an investor ;

- Brian Cesky and Alfred Lin: What is the secret of company culture?

- Ben Silberman and the Collison Brothers: Nontrivial aspects of teamwork [ 1 , 2 ];

- Aaron Levy: Developing B2B Products ;

- Reed Hoffman: On Leadership and Managers ;

- Reed Hoffman: On the leaders and their qualities ;

- Keith Rabois: Project Management ;

- Keith Rabua: Startup Development ;

- Ben Horowitz: Dismissal, promotion and reassignment ;

- Ben Horowitz: Career advice, westing and options ;

- Emmett Shire: How to conduct interviews with users;

- Emmett Shire: How to talk to users in Twitch ;

- Hossein Rahman: How hardware products are designed in Jawbone;

- Hossein Rahman: The Design Process at Jawbone.

Sam Altman: Have a nice day, today we have Peter Thiel. Peter is the founder of PayPal, Palantir and Founders Fund, who invested in many Silicon Valley technology companies. He will talk about strategy and competition. Thanks for coming, Peter.

')

Peter Thiel: Cool, Sam, thank you for inviting me.

I have a kind of “fixed idea” - [the topic of start-ups] attracts me incredibly from a business point of view: if you create a company, if you are its founder, an entrepreneur, you should always aim at creating a monopoly and try to avoid competition. And, since competition is the lot of losers, today we will talk about it.

I would like to begin with a couple of words about the basic idea that underlies the creation of a company, how you are going to provide its (company) value. What makes a business valuable?

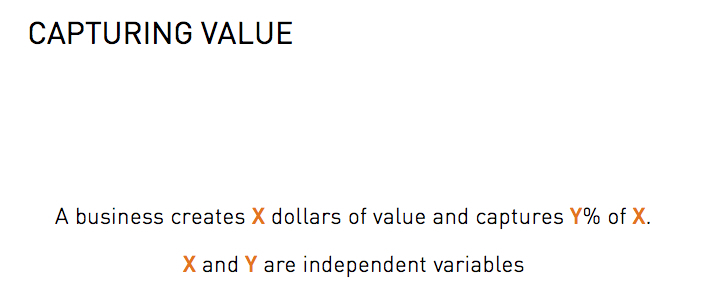

I dare to suggest that the formula for answering this question is quite simple. If your company has value, then two statements are true for you: first, the company's value for the world is expressed in a certain amount of money (X), and second, some part of this amount (Y) departs to you. People constantly lose sight of the fact that X and Y are completely independent variables, so even if X is a relatively large sum, the value of Y can be quite small. Or, X can be medium in size, which, with a sufficiently large Y value, allows your company to remain a large business.

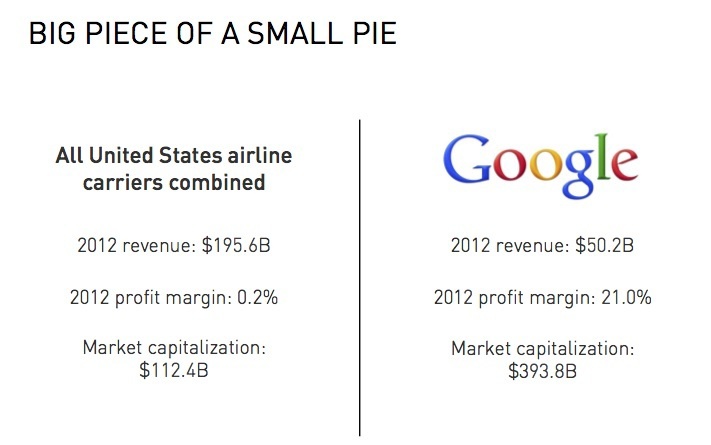

Therefore, in order to create a company with high value, you need to do something valuable on the one hand, and on the other to save some of this value to yourself. To illustrate the difference between these two concepts, I’ll give an example: try to compare the US air travel industry and a company that searches the Internet, like Google. If you measure the volume of these industries (in terms of revenue), you will conclude that air travel is much more important than search.

In 2012, air carriers earned $ 195 billion on domestic flights, and Google earned only $ 50 billion during this period. And of course, if you were faced with a choice and offered to abandon either air travel or search engines, your intuition would tell you that travel is more important than web search (I only give information on the United States).

If you look at the figures for the world as a whole, you will see that the business of air carriers is much larger than the business of web search engines, Google's business, but the profitability of the airlines is somewhat lower. The airline business was profitable in 2012, but in my opinion, the cumulative profit of air carriers in the United States for the entire century-long history of the airline industry was about zero. Companies make money, occasionally go bankrupt, reorganize their capital structure, and the whole cycle repeats again.

This is reflected in the aggregate capitalization of the air travel market, which is about a quarter of Google’s capitalization. Therefore, web search, being a much smaller industry than air travel, generates more value. This example, in my opinion, reflects the very differences in the assessment of indicators X and Y.

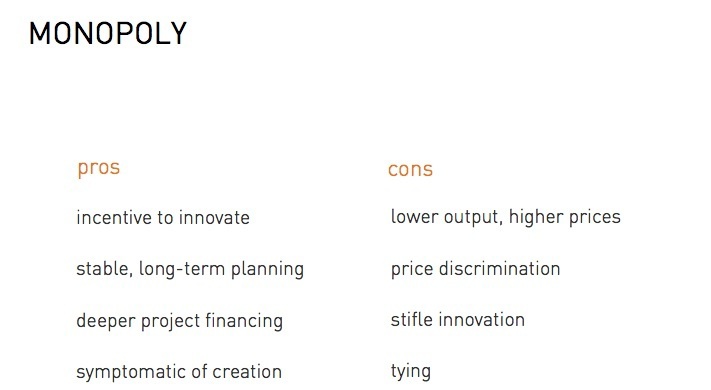

If you take the perfect competition, then it has its pros and cons. In a general sense, this is what you study as part of the basic course of economics, a condition that is very easy to model - that's why teachers of economics like to talk about perfect competition. In some ways, it is effective - especially in a world where things are static, because any company in such a system can meet growing demand.

In addition, politicians tell us that perfect competition is a blessing for society: they say we need competition, and therefore it is useful. Of course, it has many shortcomings - as a rule, work in the supercompetitive market affects the business detrimental, because in this case, it most likely does not earn. I'll come back to this.

So, in one part of the spectrum you have industries in which perfect competition thrives, and in the other - monopolies that are much more stable in terms of long-term business development and generate more capital. And if you create a creative monopoly for the invention of new products, in addition, you will inevitably generate something valuable.

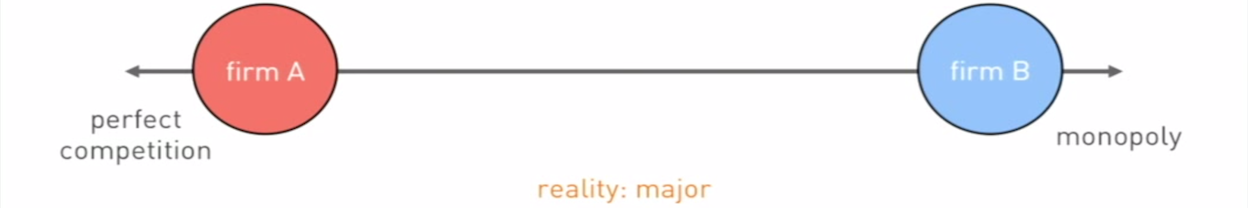

I am convinced that in terms of dividing everything into black and white (I always emphasize this) there are only two types of companies in the world. There are businesses in the market of perfect competition and there are monopoly companies. A strikingly small number of companies lie somewhere between these two extremes.

And this dichotomy is quite difficult to realize, because people are constantly lying, talking about the nature of the business in which they are involved. In my understanding, this is not necessarily the most important part of a business, but in my opinion, the idea that there are only two types of companies is something that people really do not understand.

Now I want to tell you what people are lying about. If you imagine that there is a whole spectrum of companies: from perfect competition to monopolies, then the external differences between companies within this spectrum will be insignificant, because those who manage monopolies pretend that this is not the case. You will never admit that you are running a monopoly because you do not want the antimonopoly service guys to come for you, and your company began to monitor the government.

Therefore, everyone who has a monopoly will pretend that he is in an incredible competition. On the other hand, if you are in a highly competitive environment, in a company that can barely make money, you will have to resist the temptation to lie on the opposite theme: you will say that your product is unique, that you work in a less competitive market than because you want to stand out, raise capital or something else like that.

So, if monopolists pretend that their companies are not monopolies, but non-monopolists, on the contrary, the visible differences between them will be insignificant, while the real ones will be very substantial. The distortion of the real state of affairs in business arises from the fact that people lie about the state of their companies, while the lies of some are directly opposite to the lies of others.

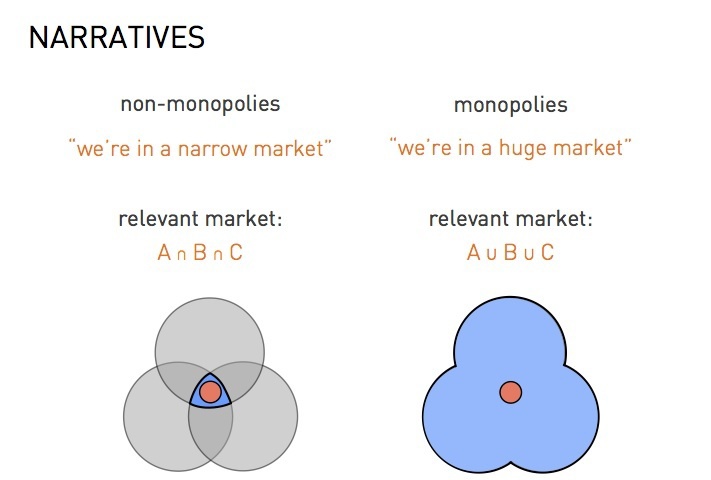

I want to delve into the description of how this lie works. So, if you are not a monopolist, you will first begin to tell you that you are working in a very small market. Otherwise, you will say that your market is much larger than it seems.

So, if we express this in the form of theoretical conditions, the monopolist will say that his business operates on a large number of isolated markets, and a non-monopolist will insist that he is at their intersection. As a result, the non-monopolist will describe his market as super-small, as if he is the only player on it. A monopolist will say that its market is extremely large, and there are many competing firms operating on it.

Here are some examples of how this works in practice. I always talk about restaurants when I want to give an example of a terrible [highly competitive] business. There is an idea that capital accumulation and competition are antonyms. If someone is accumulating capital, then in the world of perfect competition, he will go to ensure competitiveness.

Therefore, when you open a restaurant, no one wants to invest in you, and in order to raise funds, you invent a story that will help you show your personality, for example the story that “Your restaurant is the only British restaurant in Palo Alto ".

So, you are a British restaurant in Palo Alto, and your market looks really small, because you can drive right up to the Mountain View or even to Menlo Park and not meet a single person who would eat exclusively British dishes (if you don’t take the calculation of those who have long died). This is an example of a deliberately undervalued market.

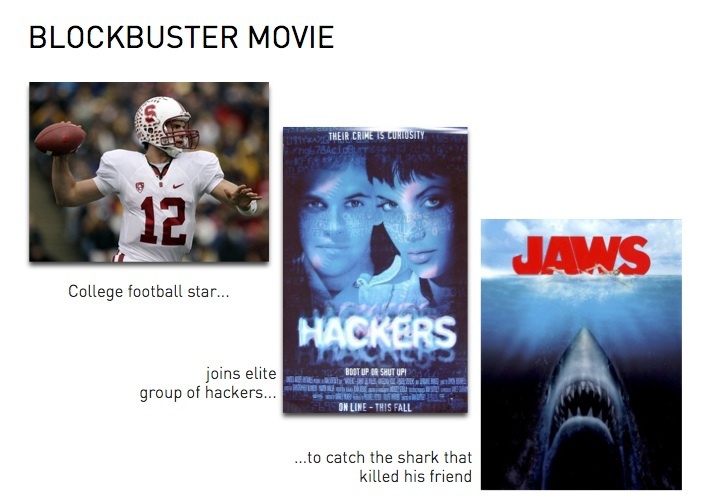

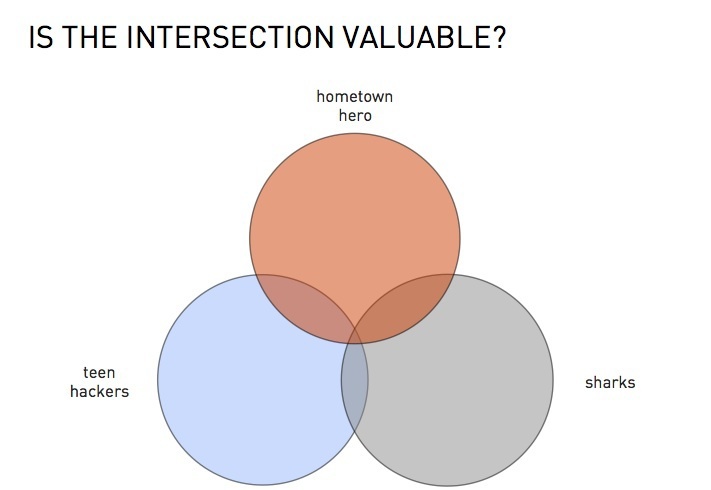

An example of such an approach exists in Hollywood - it always makes decisions about launching new films. Suppose we are talking about a picture in which the best player of a university team in American football ... joins a group of elite hackers ... to catch the shark that killed his friend. The film has not yet been shot, but the question arises: “Is this a suitable option? Or is it just another one of many other films? ” This is a super competitive environment in which it is incredibly difficult to earn. Nobody in Hollywood makes money making films - it's very, very difficult.

You probably want to know if there really can be something at the intersection of films about hackers, football players and horror movies with sharks? Does this make sense? Does such a project have any value?

Of course, there are similar examples in the world of startups - and in the worst case it’s just a jumble of “buzz words,” such as: sharing, mobile, social networks, and you juggle them to make some kind of story. Regardless of whether this is a real business or not, this is a bad sign.

It’s like pattern recognition — if you see a similar description or similar type of intersection, know that they usually don’t work.

“Something is like X, but only for Y” - it's just “nothing”: if you create Stanford, but in North Dakota, and at the same time is unique, then it is no longer Stanford.

Let's take a look at the opposite version of lies - take, for example, one company that is engaged in web search, is located not far from here, occupies a good 66% of the market and a dominant position in its segment. Google now practically does not speak about itself as a search engine, on the contrary, they use completely different descriptions: sometimes, for example, Google says that they are engaged in advertising. But if this is still a search engine, then the company's share in this market is fantastic, this is a strong monopoly, much more powerful than Microsoft in its best years, and perhaps that is why it earns so much money.

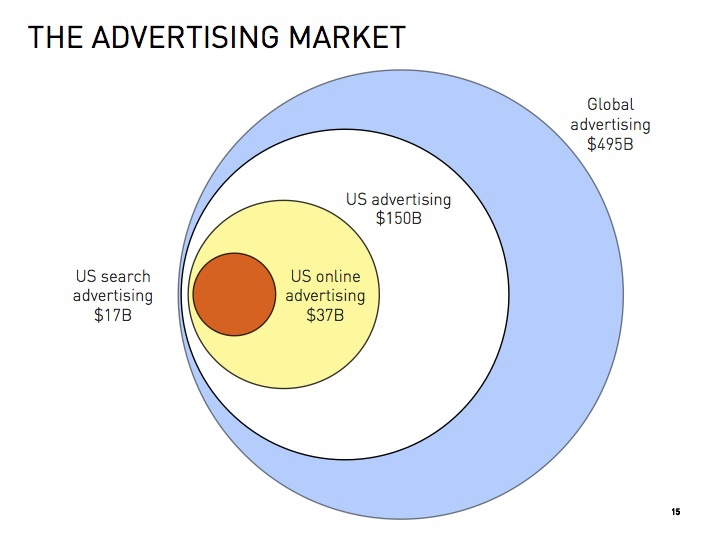

If you look at the advertising market, you will see the following: the market for advertisements in search results is estimated at $ 17 billion, and is just one of the options for displaying advertising on the Internet. And advertising on the Web, in turn, is only a share of the US advertising market as a whole, not to mention the global advertising market, which is estimated at about $ 500 billion - from this point of view, Google occupies only 3.5% of the market - this is a tiny share .

If you do not like being an advertising company, you can always call yourself a technology company. The technology market as a whole is estimated at about a trillion dollars, and in this case, Google will, “according to legend,” compete with all companies that are involved in the development of UAV cars, with Apple TV and iPhone, with Facebook, with Microsoft in the “office” market, with Amazon in the field of cloud services: this is a huge technological market, where competitors are approaching you from all sides - and there is no question of any monopoly, so the state certainly has nothing to worry about. It seems to me that one must always be alert - there are always reasons for distorting the nature of these markets in one way or another.

Evidence of the existence of small markets within the technology industry lies in the fact that all large technology companies: Apple, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, accumulate capital year after year and achieve amazingly high profitability. I would say that one of the reasons why the technology industry in the United States has been financially successful for so many years is that it has helped create monopolistic companies. This is confirmed by the fact that all these companies accumulate so much money that after a certain moment they no longer understand what to do with them.

[ The second part of the translation of Peter's lecture ]

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/245319/

All Articles