Atomic and non-atomic operations

Translation of the article by Jeff Presching Atomic vs. Non-Atomic Operations. Original article: http://preshing.com/20130618/atomic-vs-non-atomic-operations/

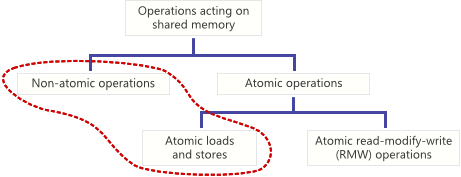

The web has already written a lot about atomic operations, but mostly the authors consider read-modify-write operations. However, there are other atomic operations, for example, atomic load operations (load) and store operations, which are no less important. In this article, I will compare atomic load and save with their non-atomic counterparts at the processor and C / C ++ compiler level. In the course of the article, we will also deal with the concept of “race condition” from the standpoint of the C ++ 11 standard.

An operation in a shared memory region is called atomic if it is completed in one step relative to other threads that have access to this memory. During the execution of such an operation on a variable, no thread can observe the change half completed. Atomic loading ensures that the variable will be loaded in its entirety at one time. Non-atomic operations do not provide such a guarantee.

')

Without such guarantees, non-blocking programming would be impossible, since it would not be possible to allow several threads to operate on one variable at the same time. We can formulate the rule:

At any time when two streams simultaneously operate on a common variable, and one of them produces a record, both streams are required to use atomic operations.

If you break this rule, and each thread uses non-atomic operations, you find yourself in a situation that C ++ 11 standard calls the state of data race (do not confuse with a similar concept from Java, or the more general concept of race condition)). The C ++ 11 standard does not explain why the race condition is bad, but claims that in this state you will get undefined behavior ( §1.10.21 ). The reason for the danger of such states of races, however, is very simple: in them the read and write operations are broken (torn read / write).

A memory operation can be non-atomic even on a single-core processor just because it uses several processor instructions. However, a single processor instruction on some platforms can also be non-atomic. Therefore, if you write portable code for another platform, you can not rely on the assumption that the individual instructions are atomic. Let's look at a few examples.

Non-atomic operations from several instructions

Suppose we have a 64-bit global variable initialized to zero.

uint64_t sharedValue = 0; At some point in time, we assign it a value:

void storeValue() { sharedValue = 0x100000002; } If we compile this code using the 32-bit GCC compiler, we get the following machine code:

$ gcc -O2 -S -masm=intel test.c $ cat test.s ... mov DWORD PTR sharedValue, 2 mov DWORD PTR sharedValue+4, 1 ret ... It can be seen that the compiler implemented a 64-bit assignment using two processor instructions. The first instruction assigns a value of 0x00000002 to the lower 32 bits, and the second puts the value 0x00000001 in the upper bits. Obviously, such an assignment is not atomic. If different threads try to access the sharedValue variable simultaneously, you can get several error situations:

- If the thread calling storeValue is interrupted between two write instructions, it will leave the value 0x0000000000000002 in memory - this is a broken write operation . If at that moment another thread tries to read sharedValue, it will get an incorrect value that no one was going to save.

- Moreover, if the recording stream was stopped between recording instructions, and another stream changes the value of sharedValue before the first stream resumes operation, we get a continuously broken record: the upper half of the variable value will be set by one stream and the lower one by the second one.

- To get a broken record on multi-core processors, threads do not even need to be interrupted: any thread running on a different core can read the value of a variable at the moment when only half of the new value is written to memory.

Parallel reading from sharedVariable also has its problems:

uint64_t loadValue() { return sharedValue; } $ gcc -O2 -S -masm=intel test.c $ cat test.s ... mov eax, DWORD PTR sharedValue mov edx, DWORD PTR sharedValue+4 ret ... Here, in the same way, the compiler implements reading in two instructions: first, the lower 32 bits are read into the EAX register, and then the upper 32 bits are read into the EDX. In this case, if a parallel record is made between these two instructions, we will get a broken read operation, even if the record was atomic.

These problems are not theoretical. The Mintomic library tests include the test_load_store_64_fail test, in which one thread saves a set of 64-bit values to a variable using a regular assignment operator, and another thread performs a normal load from the same variable, checking the result of each operation. In x86 multithreaded mode, this test drops as expected.

Non-atomic processor instructions

A memory operation may be non-atomic, even if it is executed by a single processor instruction. For example, in the ARMv7 instruction set there is an instruction strd, which stores the contents of two 32-bit registers in a 64-bit variable in memory.

strd r0, r1, [r2] On some ARMv7 processors, this instruction is not atomic. When the processor sees such an instruction, it actually performs two separate operations ( §A3.5.3 ). As in the previous example, another thread running on a different core may end up in a torn write situation. Interestingly, the situation of a broken record may occur on one core: a system interruption — say, for a planned stream context change — may occur between internal 32-bit save operations! In this case, when the thread resumes its work, it will begin executing the strd instruction again.

Another example, the well-known operation of the x86 architecture, the 32-bit mov operation is atomic when the operand in memory is aligned, and not atomic otherwise. That is, atomicity is guaranteed only in the case when a 32-bit integer is located at an address that is divisible by 4. Mintimoc contains a test case test_load_store_32_fail, which checks this condition. This test is always executed successfully on x86, but if it is modified so that the sharedInt variable is located at an unaligned address, the test will drop. On my Core 2 Quad 6600, the test crashes when sharedInt is divided between different cache lines:

// Force sharedInt to cross a cache line boundary: #pragma pack(2) MINT_DECL_ALIGNED(static struct, 64) { char padding[62]; mint_atomic32_t sharedInt; } g_wrapper;

I think we have considered enough nuances of processor execution. Let's take a look at atomicity at the C / C ++ level.

All C / C ++ operations are considered non-atomic.

In C / C ++, each operation is considered non-atomic until the other is explicitly indicated by the compiler or hardware platform producer — even regular 32-bit assignment.

uint32_t foo = 0; void storeFoo() { foo = 0x80286; } Language standards say nothing about atomicity in this case. Perhaps integer assignment is atomically, maybe not. Since non-atomic operations do not provide any guarantees, ordinary integer assignment in C is non-atomic by definition.

In practice, we usually have some information about the platforms for which the code is generated. For example, we usually know that on all modern x86, x64, Itanium, SPARC, ARM, and PowerPC processors, normal 32-bit assignments are atomically if the destination variable is aligned. You can verify this by rereading the relevant section of the processor and / or compiler documentation. I can say that in the gaming industry, the atomicity of so many 32-bit assignments is guaranteed by this particular property.

Anyway, when writing really portable C and C ++ code, we follow the long established tradition of believing that we know nothing more than what the standards of the language tell us. Portable C and C ++ are designed to run on any possible computing device of the past, present, and future. I, for example, like to represent a device whose memory can be changed only by pre-filling it with random garbage:

On such a device, you certainly do not want to perform a parallel readout, as well as the usual assignment, because the risk of getting a random value is too high.

In C ++ 11, there finally emerged a way to perform truly portable atomic saves and loads. These operations performed using the atomic library C ++ 11 will work even on the conditional device described earlier: even if it means that the library will have to block the mutex in order to make each operation atomic. My recently released Mintomic library does not support such a number of different platforms, but it works on some older computers, it is manually optimized and non-blocking guaranteed.

Relaxed atomic operations

Let's go back to the example with sharedValuem that we looked at at the beginning. Let's rewrite it using Mintomic so that all operations are performed atomically on each platform that Mintomic supports. To begin with, we declare sharedValue as one of the Mintomic atomic types:

#include <mintomic/mintomic.h> mint_atomic64_t sharedValue = { 0 }; The mint_atomic64_t type guarantees correct alignment in memory for atomic access on each platform. This is important because, for example, the gcc 4.2 compiler for ARM in the Xcode 3.2.5 development environment does not guarantee that the uint64_t type will be 8-byte aligned.

In the storeValue function, instead of performing the usual non-atomic assignment, we need to execute mint_store_64_relaxed.

void storeValue() { mint_store_64_relaxed(&sharedValue, 0x100000002); } Similarly, in loadValue, we call mint_load_64_relaxed.

uint64_t loadValue() { return mint_load_64_relaxed(&sharedValue); } If you use the terminology of C ++ 11, then these functions are now free from data race conditions (data race free). If they are called at the same time, it is absolutely impossible to find yourself in a situation of a broken read or write, regardless of which platform the code is running: ARMv6 / ARMv7 (Thumb or ARM modes), x86, x64 or PowerPC. If you are interested in how mint_load_64_relaxed and mint_store_64_relaxed work, then both functions use the cmpxchg8b instruction on the x86 platform. Implementation details for other platforms can be found in the Mintomic implementation .

Here is the same code using the standard C ++ 11 library:

#include <atomic> std::atomic<uint64_t> sharedValue(0); void storeValue() { sharedValue.store(0x100000002, std::memory_order_relaxed); } uint64_t loadValue() { return sharedValue.load(std::memory_order_relaxed); } uint64_t loadValue() { return mint_load_64_relaxed(&sharedValue); } You should have noticed that both examples use relaxed atomic operations, as evidenced by the _relaxed suffix in identifiers. This suffix is reminiscent of certain guarantees regarding memory ordering.

In particular, for such operations, reordering of memory operations is allowed in accordance with reordering by the compiler or with memory reordering by the processor . The compiler can even optimize redundant atomic operations, as well as non-atomic ones. But in all these cases, the atomicity of the operations is preserved.

I think that in the case of parallel operations with memory, using the functions of the Mintomic or C ++ 11 atomic libraries is a good practice, even if you are sure that the usual read or write operations will be atomic on the platform you use. The use of atomic libraries will serve as an extra reminder that variables can be used in a competitive environment.

Hopefully, it has now become clearer to you why the world's simplest non-blocking hash table uses Mintomic to manipulate shared memory simultaneously with other threads.

About the author. Jeff Preshing works as a software architect at Ubisoft, a gaming company, specializing in multi-threaded programming and non-blocking algorithms. This year, he gave a report on multi-threaded game development in accordance with the C ++ 11 standard at the CppCon conference, the video of this report was on Habré . He maintains an interesting blog, Preshing on Programming , including the subtleties of non-blocking programming and the associated nuances of C ++.

I would like to translate many articles from his blog for the community, but since his posts often refer to one another, it’s quite difficult to select an article for the first translation. I tried to choose an article that would be minimally based on others. Although the question under consideration is quite simple, I hope it will still be interesting to many who are starting to get acquainted with multithreaded programming in C ++.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/244881/

All Articles