Orthogonal - a model of the world with an alternative theory of relativity

In 2011-2013 Australian writer Greg Egan published the Orthogonal trilogy (The Clockwork Rocket, The Ethernal Flame, The Arrows of Time). The books describe a wonderful world in which there are no liquids and electric charges, four-eyed intelligent creatures that can change shape and reproduce by division, using air not for chemical reactions, but for cooling their body, and light for transmitting nerve impulses inhabit. The speed of light in this world is not constant: violet photons move much faster than red. Therefore, the stars do not look like white dots, but as rainbow stripes.

In 2011-2013 Australian writer Greg Egan published the Orthogonal trilogy (The Clockwork Rocket, The Ethernal Flame, The Arrows of Time). The books describe a wonderful world in which there are no liquids and electric charges, four-eyed intelligent creatures that can change shape and reproduce by division, using air not for chemical reactions, but for cooling their body, and light for transmitting nerve impulses inhabit. The speed of light in this world is not constant: violet photons move much faster than red. Therefore, the stars do not look like white dots, but as rainbow stripes.Even in the first book, the heroes found out that the reason for such behavior of light lies in the properties of the space-time of their universe: unlike our world, which is the Minkowski space, their spatial and temporal coordinates are completely equal. Any body moves along its trajectory in four-dimensional space-time at a constant speed, uniform motion there looks like a straight line, and accelerated - like an arc. For example, the flight of a spacecraft to another star and back can be represented with the following picture:

We consider the ship's thrust during acceleration and deceleration to be constant, and in this case the trajectory of its movement in space-time will be an arc of a circle. For a finite time, the ship will reach an infinite (according to the clock of a stationary observer) speed, and the main part of the flight will take place in zero time. At the same time, the time for the passengers of the ship will go as usual, and it can be measured along the length of the trajectory in the figure. When the ship returns to the starting point, it turns out that only a few years have passed on the home planet, while centuries could have passed for the passengers of the ship. Moreover, if the acceleration / deceleration phases last a little longer, the ship may return at the very moment it started, and maybe even earlier:

True, the universe will have to somehow solve the paradoxes arising from this, and these decisions may be unexpected for the inhabitants of the planet.

Photons obey the same laws as other bodies. They are characterized by the presence of natural oscillations. All photons are the same, and in their own frame of reference they have the same frequency (and zero wavelength). But when an observer sees photons moving at different speeds, their frequencies seem to him to be different. The red light (the slowest one) has a minimum frequency and wavelength, while a violet one has a maximum:

Here the red line is the trajectory of the red photon, and the violet is the path of the violet, respectively. The eye sees photons, whose trajectories are between these lines.

The heroes of the book see light in the speed range from 76/144 to 192/144 from the speed of blue light (blue photons are those that fly in space-time at an angle of 45 degrees to the observer, that is, their apparent speed in space is equal to the speed of any reference systems in space-time). Thus, the observer sees only those photons whose trajectory lies between two cones:

The half angle at the apex of the inner (red) cone is 27 degrees, and the outer (violet) angle is 54 degrees. If the star's trajectory crosses this space, then the star is visible:

Here was considered a slowly moving star. If the speed of the star becomes greater, then the trajectory will consist of two parts:

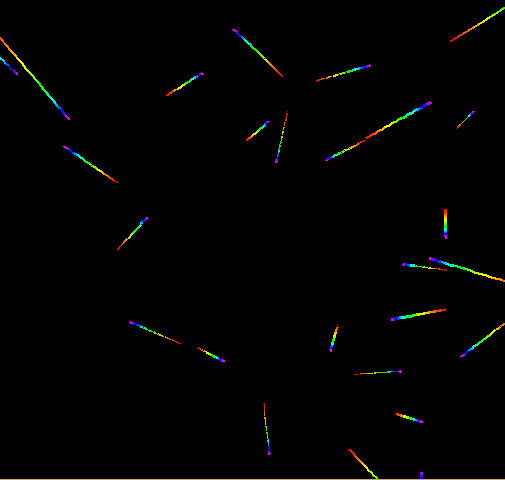

Soon after the beginning of the trilogy, strange stars began to appear in the sky - Hartlers (Hurtler - a pest?). They appeared as purple dots, from which rainbow stripes quickly diverged in two directions:

Heroes have assumed (and correctly) that Hartlers are stars whose trajectory is perpendicular to the trajectory of their world. That is, each such star exists only at one moment in time, but at the same time occupies its entire trajectory. In space-time, it could look like this:

But if you look closely at this picture, it turns out that half of the trajectory, directed in the direction of the Hartler motion, is formed by photons that fly back in time in the Hartler frame of reference! Judging by the content of the third book, the stars do not emit such photons, so in reality the picture should look like this:

I wondered what this Universe would look like if you navigate through it in a very maneuverable ship. For this, I decided to write a game with the simplest plot - there is the Universe, there are several stars in it that need to be visited and extinguished (just flying side by side).

The first question was how to choose the form of space-time. The heroes of the trilogy quickly came to the conclusion that the Universe should be finite, but for a long time they doubted which one. As a result, they came to the conclusion that it should be a four-dimensional sphere (that is, a sphere in 5-dimensional space). True, they for some reason needed to have areas with negative curvature (otherwise there were some problems with entropy), that is, the sphere must be of a distorted shape. But for simplicity, I took the usual homogeneous sphere.

The position and speed of the ship are described by a pair of perpendicular vectors. The vector P determines the current position in space, V is the direction of the drift (the drift velocity is always the same). In addition, we need three vectors X, Y, Z, which determine the orientation of the ship in space (and the image on the screen). All vectors are taken in 5-dimensional space, have a length of 1 and are perpendicular to each other. Thus, the ship is described by an orthogonal matrix of 5 * 5.

It turns out that all the movements and maneuvers of the ship in this view are just turns of the matrix in the coordinate planes. General drift - rotation in the plane (P, V) (vectors X, Y, Z remain unchanged), acceleration and deceleration in 3D - turns in the plane (V, Z), lateral accelerations - turns in (V, X) and in ( V, Y), change of orientation of the ship - rotation in (X, Z) and (Y, Z). Rotation speeds are determined by the general parameters of the game, and they can be changed on the control panel.

The star's trajectory is also a pair of perpendicular vectors (P0, V0). At any time moment T (according to the clock of the star itself) its position will be P1 = P0 * cos (T) + V0 * sin (T), and the drift velocity will be V1 = V0 * cos (T) -P0 * sin (T). To get an image of a star, we need to determine the parameters of a photon emitted from a point (P1, V1) and flown to our point (P, V): what color it will be and from which side it will fly. To do this, it is enough for us to connect the points P and P1 by the arc of the large circle and see which way it goes from the point P and which side it enters into P1.

For simplicity, we assume that the photon cannot fly more than a quarter of a circle. In fact, the book does not say anything about the image of a star, visible from the night side of the planet, or about phantom stars from the opposite edge of the Universe, the light from which was focused in the vicinity of the world of the heroes of the trilogy. This means that it is enough for us to consider the case when the angle between the vectors P and P1 is acute, i.e. (P, P1)> 0. It turns out that firstly, the condition (P, V1)> 0 is necessary - otherwise the star would have to emit a photon into the past, secondly, (P1, V)> 0 - otherwise the photon will fly to us from the future, and without special means we can not see it.

After that, it is enough for us to project the vector P1 onto the space (V, X, Y, Z) (Tangent to the sphere at the point P). Let the vector S = (v, x, y, z) be obtained. Then the length L of the vector S corresponds to the distance that the photon traveled (more precisely, is equal to its sine), the value v / L is the cosine of the angle between the photon trajectory and our trajectory in spacetime, which determines the color of the photon, and (x, y, z) - the direction from which the photon flew - and we can portray it with the usual methods.

It turns out that catching the stars is not easy at all. The simplest case is when the star is close, and our speeds do not differ very much (as was the case with the first figure with cones). With the help of side engines, we can easily eliminate lateral speeds. The star on the screen will turn into a point from the rainbow strip, our trajectories in space-time will be in the same plane, and we will fly to the star () or from it - it is difficult to say in advance).

Natural desire - to aim at the star and begin to accelerate. But what happens?

It can be seen that the trajectory section that we see is getting farther and farther away - in fact, we are starting to see the star's ever more distant past. In addition, the visible star is removed, and becoming smaller and dimmer. And if we have at least a small lateral displacement, then we will see that the red part of the trajectory is reduced, ending on the green, and then on the blue part of the spectrum.

At this point, you can slightly slow down and wait until the star becomes larger in size. And then start catching her. But what if we miss?

From the side where we looked, the purple part of the track suddenly changes to red, and we will see that it is being removed. And the star itself will be on the opposite side from us. So we need to turn the ship around and move to the star again.

But to catch a nearby star is not very difficult. Problems begin when the star is far away, and we see a long and thin rainbow trail. Where to look for a star, where to fly - it is absolutely impossible to understand. Sometimes I do it. More often not.

If you want to experiment with this space - the exe-file can be taken here (for .NET 3.5), and the source code is here .

A more detailed description of the laws of physics of this world (up to the quantum level) is on the author's website of the trilogy: www.gregegan.net

')

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/238345/

All Articles