Memory addresses: physical, virtual, logical, linear, efficient, guest

I occasionally have to explain to different people certain aspects of the Intel® IA-32 architecture, including the intricacy of the data addressing system in memory, which seems to have implemented almost all of the ideas that were invented. I decided to issue a detailed answer in this article. I hope that it will be useful to someone else.

When executing machine instructions, data that can be in several places is read and written: in the registers of the processor itself, in the form of constants encoded in the instructions, as well as in RAM. If the data is in memory, then their position is determined by some number - the address. For a number of reasons, which I hope will become clear in the process of reading this article, the original address, encoded in the instructions, goes through several transformations.

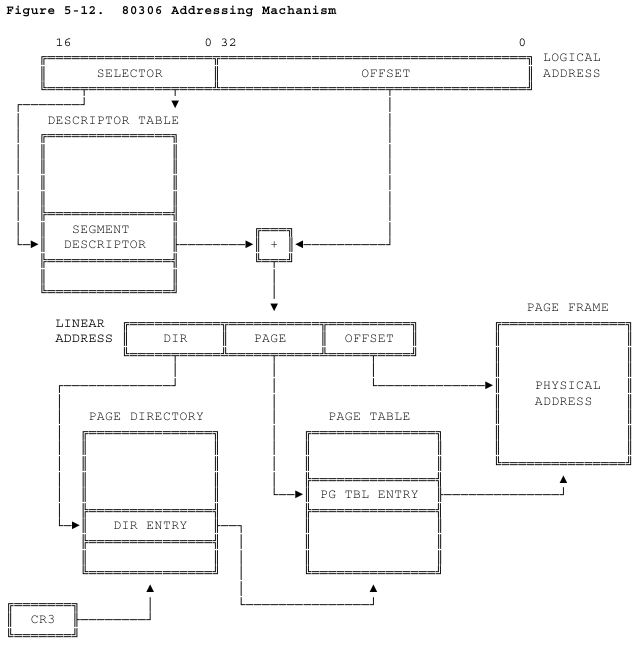

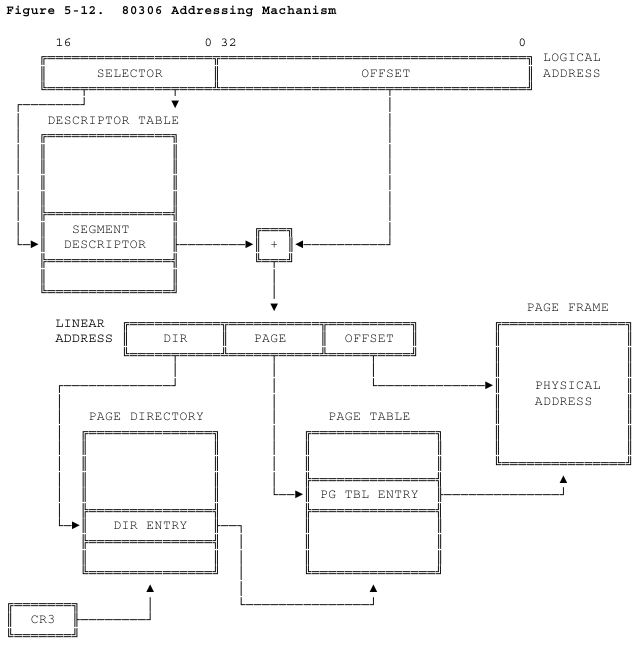

The figure shows the segmentation and page conversion of the address, as they looked 27 years ago. Illustration of Intel's 80386 Programmers's Reference Manual 1986. It's funny that in the description of the picture there are already two typos: "803 0 6 Addressing M a chanism". Nowadays, the address is subject to more complex transformations, and illustrations are no longer done in pseudographics.

Let's start a little from the end - from the goal of the whole chain of transformations.

')

The end result of all the transformations of the other address types listed later in this article is the physical address . It ends the work inside the CPU to convert addresses.

An effective address is the beginning of the journey. It is specified in the arguments of an individual machine instruction, and is calculated from the values of the registers, the offsets and scaling factors specified in it explicitly or implicitly.

For example, for instructions (assembler in AT & T notation)

the effective address of the operand-destination will be calculated by the formula:

Without knowing the number and parameters of the segment in which the effective address is indicated, the latter is useless. The segment itself is selected by another number, called the selector . A pair of numbers, written as

Here, usually for those who are confronted with these concepts for the first time, the head starts spinning. Somewhat simplify (or complicate) the situation helps the fact that almost always the choice of the selector (and its associated segment) is made on the basis of the "meaning" of access. By default, unless otherwise stated in the encoding of the machine instruction, logical addresses with the CS selector are used to obtain the code addresses, with DS for the data, and with SS for the stack.

The effective address is the offset from the beginning of the segment - its base. If we add the base and the effective address, we get a number called the linear address :

The logical → linear transformation may not always be successful, since when it is executed, several conditions are checked for the properties of the segment recorded in the fields of its descriptor. For example, checking for overstep and access rights.

Segmentation was fashionable at some stage in the development of computing technology. At present, it has been replaced almost everywhere by other mechanisms, and is used only for specific tasks. So, in IA-32e (64-bit) mode, only two segments can have a non-zero base. For the other four in this mode, the linear address is always == effective.

In the literature and in the documentation of other architectures there is another term - a virtual address . It is not used in the Intel documentation on IA-32, but is found, for example, in the description of Intel® Itanium, in which segmentation is not used. We can safely assume that for IA-32 virtual == linear.

In the Soviet literature on computer technology, this kind of address was also called mathematical .

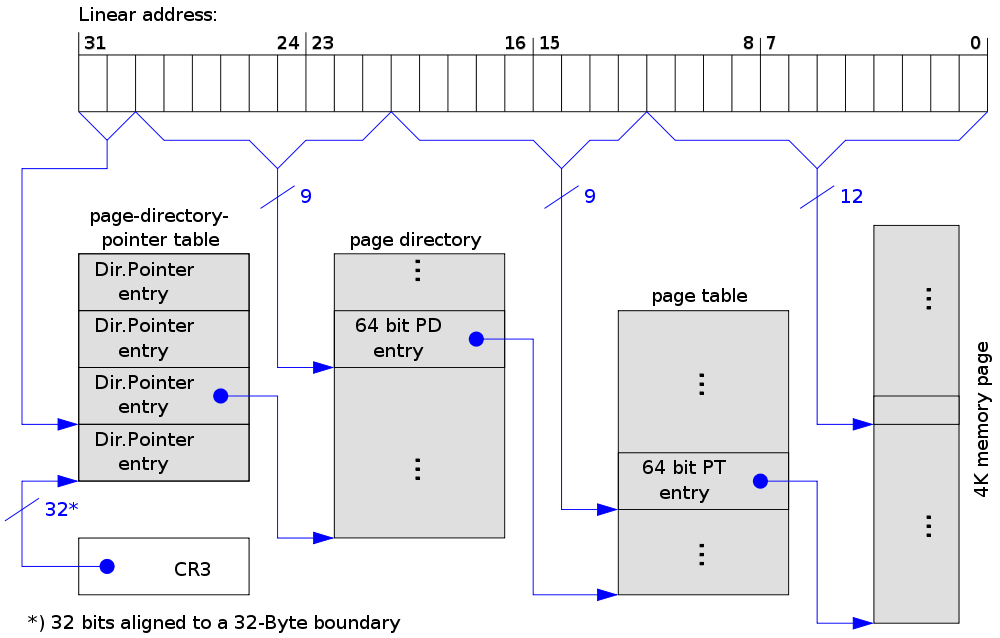

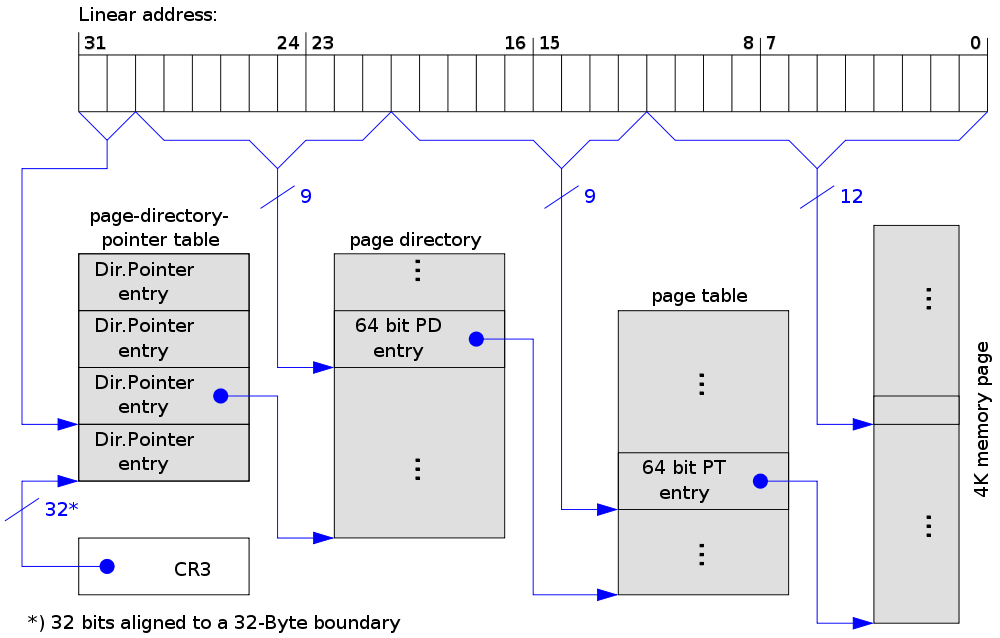

The following address transformation after segmentation: linear → physical - has many variations in its algorithm, depending on the mode (32-bit, PAE or 64-bit) the processor is in.

However, the general idea is always the same: a linear address is divided into several parts, each of which serves as an index in one of the system tables stored in memory. The entries in the tables are the addresses of the beginning of the table of the next level or, for the last level, the required information about the physical address of the page in memory and its properties. The least significant bits are not converted, but are used for addressing within the found page. For example, for the PAE mode with a 4 KB page size, the conversion looks like this:

In different modes of the processor, the number and capacity of these tables differ. Conversion can fail if the next table does not contain valid data, or the access rights stored in the last one prohibit access to the page; for example, when writing to regions marked as read-only, or trying to read kernel memory from an unprivileged process.

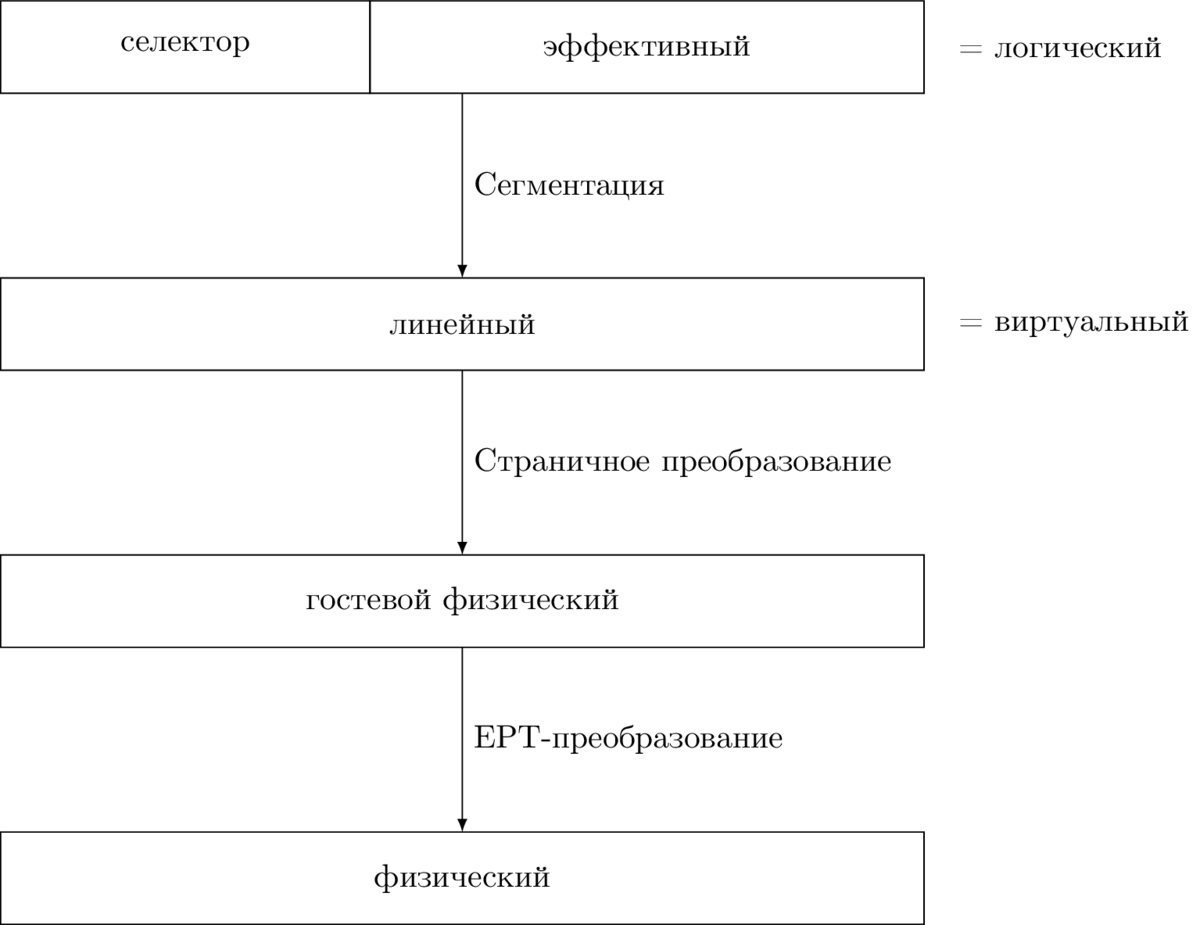

Prior to the introduction of hardware virtualization capabilities in Intel processors, page conversion was the last in the chain. When several virtual machines are running on the same system, the physical addresses obtained in each of them must be translated one more time. This can be done in software, or in hardware, if the processor supports EPT functionality (Extended Page Table). The address, formerly known as physical, was renamed guest physical in order to distinguish it from real physical. They are related via EPT conversion. The algorithm of the latter is similar to the previously described page transformation: a set of related tables with a common root, the last level of which determines whether there is a physical page for the specified guest physical.

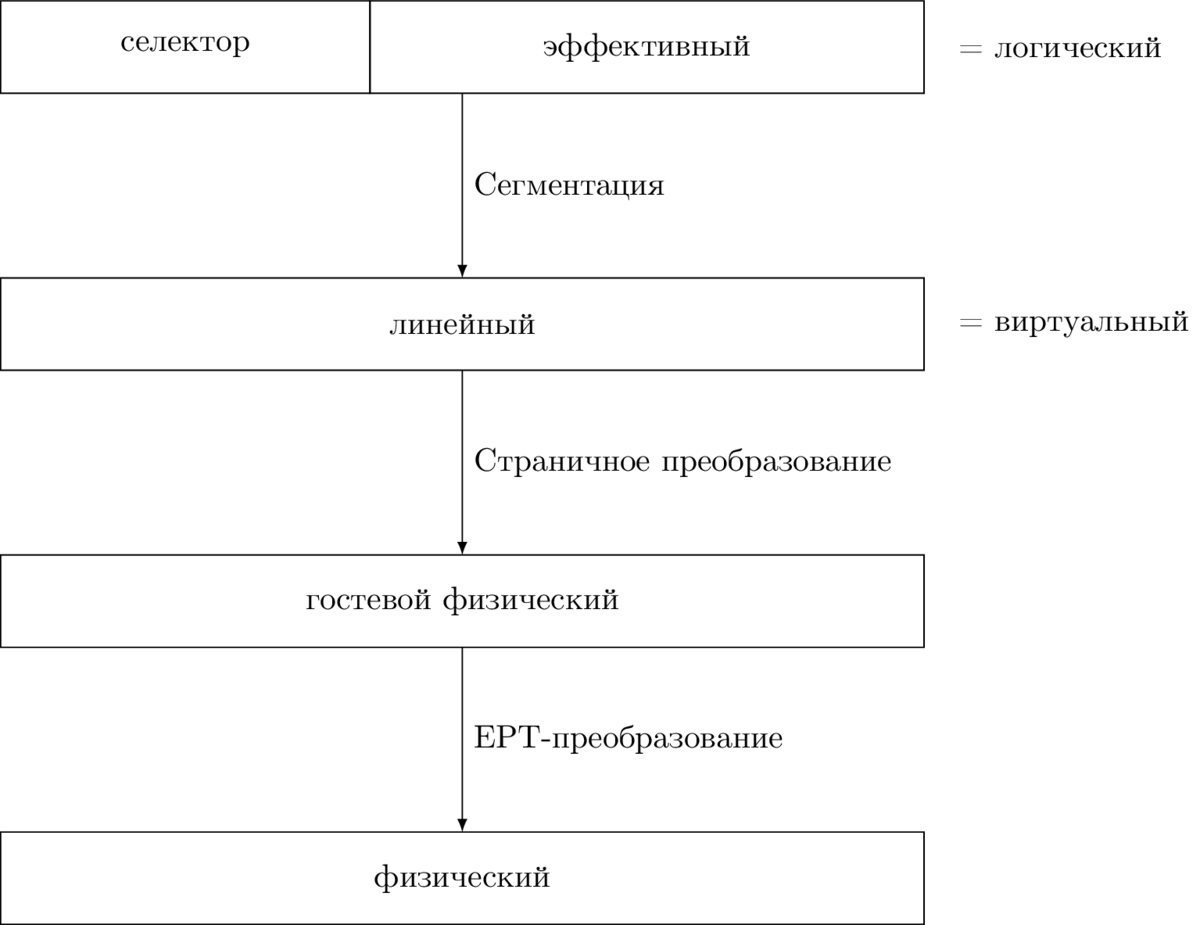

I tried to collect all address mappings into one illustration. In it, the transformations are indicated by arrows, the address types are outlined in frames.

As mentioned above, each of the transformations can return an error for addresses that have no idea in the next form in the chain. Solving such problems is the task of operating systems and virtual machine monitors that implement the abstraction of virtual memory.

Evolution, that in nature, that in technology is a strange thing. It gives rise to unexpected structures that are inexplicable from a rational design point of view. Her creations are full of atavism, the rules of their behavior sometimes consist almost entirely of exceptions. In order to understand the work of such a system, it is often necessary to scroll through its evolution from the very beginning, and under the heaps of all layers find the truth in the form of the principle: “do not throw anything away”. I tend to consider the IA-32 architecture to be a great example of evolution.

Thanks for attention!

When executing machine instructions, data that can be in several places is read and written: in the registers of the processor itself, in the form of constants encoded in the instructions, as well as in RAM. If the data is in memory, then their position is determined by some number - the address. For a number of reasons, which I hope will become clear in the process of reading this article, the original address, encoded in the instructions, goes through several transformations.

The figure shows the segmentation and page conversion of the address, as they looked 27 years ago. Illustration of Intel's 80386 Programmers's Reference Manual 1986. It's funny that in the description of the picture there are already two typos: "803 0 6 Addressing M a chanism". Nowadays, the address is subject to more complex transformations, and illustrations are no longer done in pseudographics.

Let's start a little from the end - from the goal of the whole chain of transformations.

')

Physical adress

The end result of all the transformations of the other address types listed later in this article is the physical address . It ends the work inside the CPU to convert addresses.

Final result?!

In fact, it is easy to understand that this is not the end. In a platform that must process a request for data from the processor, there may be several DRAM chips that have their own blocking structure, as well as various peripheral devices mapped to the total physical memory space. The further transaction path with a certain physical address will depend on the configuration of several decoders that are on its way inside the platform devices.

Effective Address

An effective address is the beginning of the journey. It is specified in the arguments of an individual machine instruction, and is calculated from the values of the registers, the offsets and scaling factors specified in it explicitly or implicitly.

For example, for instructions (assembler in AT & T notation)

addl %eax, 0x11(%ebp, %edx, 8)

the effective address of the operand-destination will be calculated by the formula:

eff_addr = EBP + EDX * 8 + 0x11

Logical address

Without knowing the number and parameters of the segment in which the effective address is indicated, the latter is useless. The segment itself is selected by another number, called the selector . A pair of numbers, written as

selector:offset , received the name logical address . Since active selectors are stored in a group of special registers, most often instead of the first number in a pair, the register name is recorded, for example, ds: 0x11223344.Here, usually for those who are confronted with these concepts for the first time, the head starts spinning. Somewhat simplify (or complicate) the situation helps the fact that almost always the choice of the selector (and its associated segment) is made on the basis of the "meaning" of access. By default, unless otherwise stated in the encoding of the machine instruction, logical addresses with the CS selector are used to obtain the code addresses, with DS for the data, and with SS for the stack.

Line Address

The effective address is the offset from the beginning of the segment - its base. If we add the base and the effective address, we get a number called the linear address :

lin_addr = segment.base + eff_addr

The logical → linear transformation may not always be successful, since when it is executed, several conditions are checked for the properties of the segment recorded in the fields of its descriptor. For example, checking for overstep and access rights.

Real mode

The above is true with segmentation enabled. In 16-bit real mode, the meaning of the selectors is different, they only store the base, and the conversion does not perform segment checks. In fact, the designations CS, DS, FS, GS, ES, SS have completely different meanings in these two modes, which adds confusion.

Segmentation was fashionable at some stage in the development of computing technology. At present, it has been replaced almost everywhere by other mechanisms, and is used only for specific tasks. So, in IA-32e (64-bit) mode, only two segments can have a non-zero base. For the other four in this mode, the linear address is always == effective.

What is a virtual address?

In the literature and in the documentation of other architectures there is another term - a virtual address . It is not used in the Intel documentation on IA-32, but is found, for example, in the description of Intel® Itanium, in which segmentation is not used. We can safely assume that for IA-32 virtual == linear.

In the Soviet literature on computer technology, this kind of address was also called mathematical .

Page conversion

The following address transformation after segmentation: linear → physical - has many variations in its algorithm, depending on the mode (32-bit, PAE or 64-bit) the processor is in.

What affects paging

It is noteworthy how many different bits from different system registers of the processor affect the paging conversion process at present. I reviewed the latest September edition of Intel SDM [1], and here is the complete list: CR0.WP, CR0.PG, CR4.PSE, CR4.PAE, CR4.PGE, CR4.PCIDE, CR4.SMEP, CR4.SMAP, IA32_EFER. LME, IA32_EFER.NXE, EFLAGS.AC.

However, the general idea is always the same: a linear address is divided into several parts, each of which serves as an index in one of the system tables stored in memory. The entries in the tables are the addresses of the beginning of the table of the next level or, for the last level, the required information about the physical address of the page in memory and its properties. The least significant bits are not converted, but are used for addressing within the found page. For example, for the PAE mode with a 4 KB page size, the conversion looks like this:

In different modes of the processor, the number and capacity of these tables differ. Conversion can fail if the next table does not contain valid data, or the access rights stored in the last one prohibit access to the page; for example, when writing to regions marked as read-only, or trying to read kernel memory from an unprivileged process.

Guest Physical

Prior to the introduction of hardware virtualization capabilities in Intel processors, page conversion was the last in the chain. When several virtual machines are running on the same system, the physical addresses obtained in each of them must be translated one more time. This can be done in software, or in hardware, if the processor supports EPT functionality (Extended Page Table). The address, formerly known as physical, was renamed guest physical in order to distinguish it from real physical. They are related via EPT conversion. The algorithm of the latter is similar to the previously described page transformation: a set of related tables with a common root, the last level of which determines whether there is a physical page for the specified guest physical.

Full picture

I tried to collect all address mappings into one illustration. In it, the transformations are indicated by arrows, the address types are outlined in frames.

As mentioned above, each of the transformations can return an error for addresses that have no idea in the next form in the chain. Solving such problems is the task of operating systems and virtual machine monitors that implement the abstraction of virtual memory.

Conclusion

Evolution, that in nature, that in technology is a strange thing. It gives rise to unexpected structures that are inexplicable from a rational design point of view. Her creations are full of atavism, the rules of their behavior sometimes consist almost entirely of exceptions. In order to understand the work of such a system, it is often necessary to scroll through its evolution from the very beginning, and under the heaps of all layers find the truth in the form of the principle: “do not throw anything away”. I tend to consider the IA-32 architecture to be a great example of evolution.

PS Just like everyone else

Shortly after writing this article, I came across a presentation about the IBM System z architecture, which is notable for its long and interesting history of supporting virtualization. This document contains an enumeration of all types of memory addresses used in System z:

As you can see, there are five of them too.

- Virtual: real-world address translation (DAT) to real addresses

- Real: Translated to absolute addresses using the prefix register

- Absolute: After applying the prefix register

- Logical: The address seen by the program.

- Physical: translated to absolute addresses by the Config Array

As you can see, there are five of them too.

Thanks for attention!

Literature

- Intel Corporation. Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual. Volumes 1-3, 2014. www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/processors/architectures-software-developer-manuals.html

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/238091/

All Articles