Virtualization¹

In the previous part, I talked about three IA-32 modes: protected, VM86, and SMM. Although it is not customary to associate them with virtualization, they serve to create isolated environments for programs executed on the processor. In this article, I will describe the “real” Intel VT-x virtualization technology. I want to show how the theory of effective virtualization manifests itself in every aspect of its practical implementation.

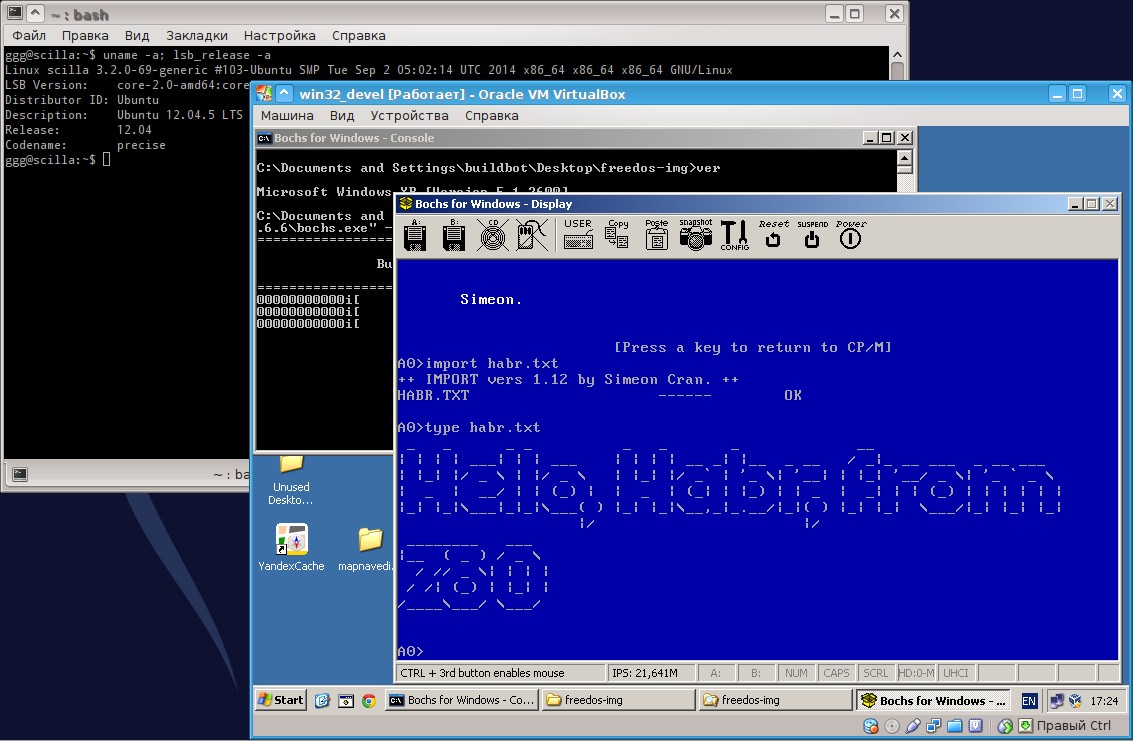

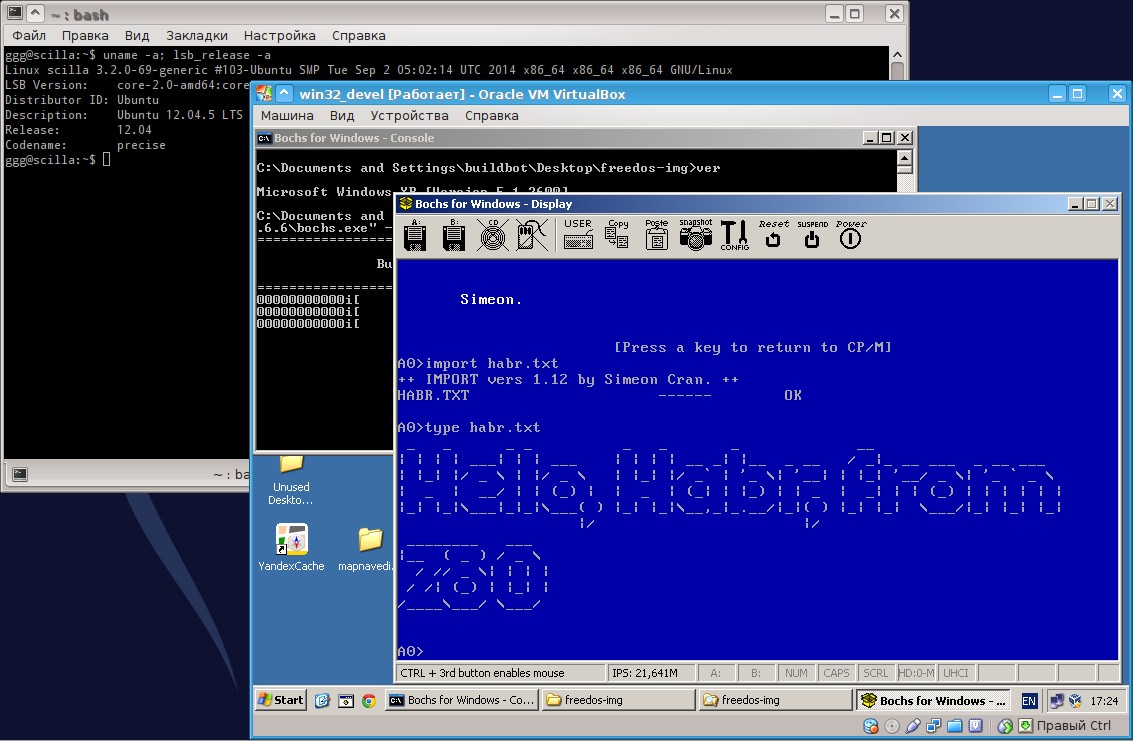

On CDTV: Launched under Ubuntu Linux, the Oracle VirtualBox program, which runs MS Windows XP, runs the Bochs simulator, which runs the FreeDOS operating system, which runs the MYZ80 simulator for the Z80 processor, which has the CP / CP loaded M (in full screen mode).

In 2006, Intel introduced the VT-x, an extension for efficiently virtualizing the IA-32 architecture. It includes a set of VMX instructions and two new modes of operation. I do not want to repeat all the documentation here, it’s very boring to write as well as read. However, I will describe some features of the interfaces proposed in it.

')

It was impossible to manage to virtualize the already existing processor modes, since a number of IA-32 instructions that existed at that time were official, but not privileged, and, according to the theory , they could not be effectively intercepted and emulated. The new modes were called root and non-root, and they, in general, are orthogonal to all classical modes (although there are features here, see below). The first one is for the virtual machine monitor, the second one is for guest environments. By default, after power-up, virtualization is not available. Logging in to root mode occurs after the execution of the new VMXON instruction, and subsequent logins to non-root using VMLAUNCH / VMRESUME.

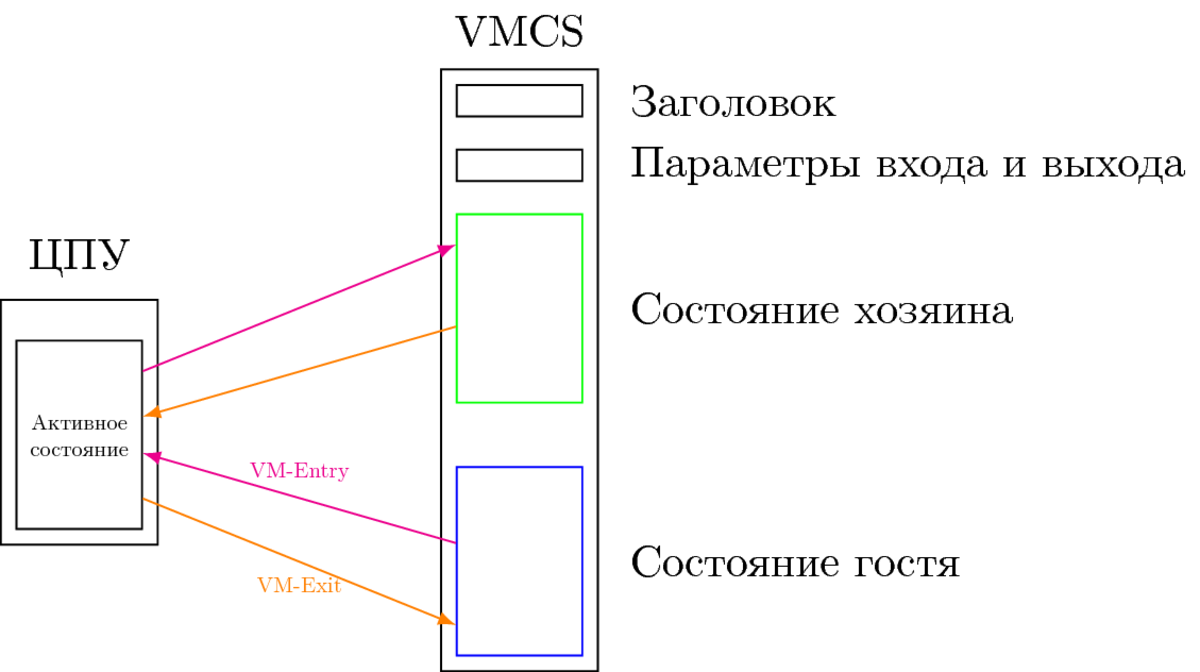

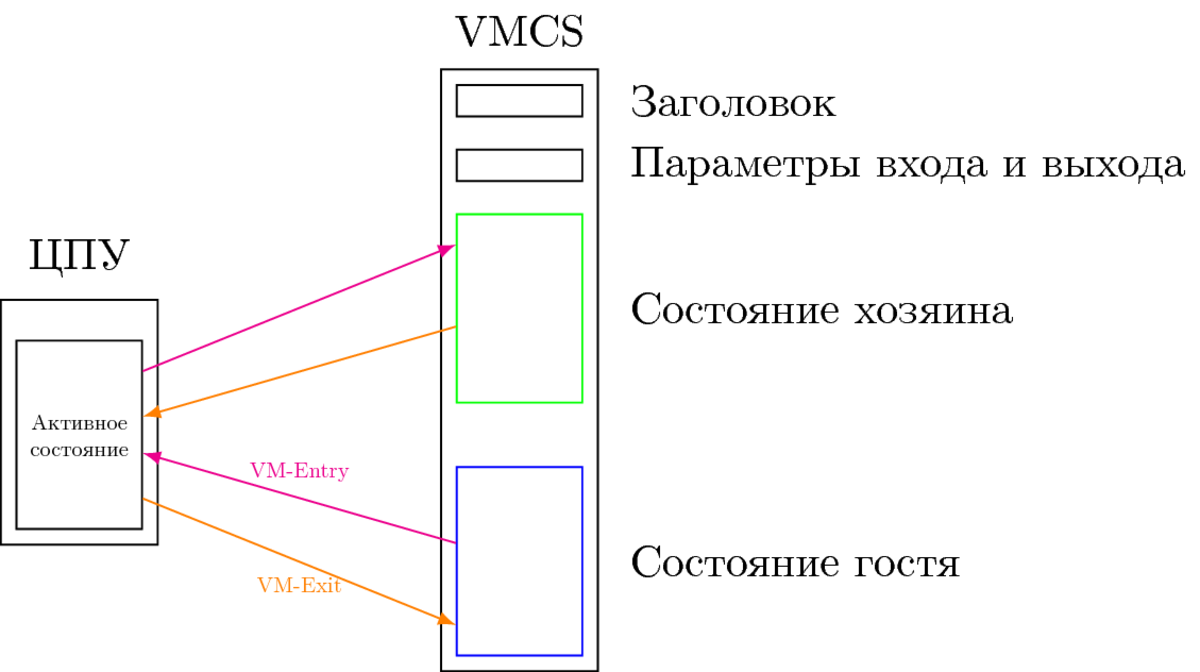

The key process in any hardware virtualization system is saving the current state of the guest processor and loading the monitor state. In VT-x, everything here is done strictly according to the theory mentioned. An entity called VMCS (Virtual Machine Control Structure) is used to store the state of both the guest and the host. This structure should be different for each active guest. In the following figure, which illustrates transitions between root and non-root modes, two areas are used within VMCS: guest state (guest-state) and host state (host-state).

In this figure, the VM-Entry event is one of two instructions: VMLAUNCH or VMRESUME, and VM-Exit is one of the many synchronous and asynchronous events declared privileged in the context of non-root VT-x and therefore requiring monitor interception. Details of what and how to load when switching from root to non-root and back are also stored in the so-called VMCS. VM-entry and VM-exit controls, “entry and exit parameters”. The storage areas are divided into fields, each of which stores the register or other architectural information of the processor.

I want to show how carefully the creators of VT-x approached versioning and backward compatibility with future implementations. The key design element here is the amazing (considering its low level) abstractness of the proposed interface. Instead of describing the layout of the VMCS structure in memory and allowing it to work with conventional LOAD and STORE instructions, two new instructions were introduced: VMREAD and VMWRITE. And they do not operate with byte offsets within the structure, but with encodings of individual fields. Moreover, it is not even guaranteed that all fields in memory store actual values. The processor can cache some of them, thus speeding up the process of switching modes - data does not have to be loaded from slow memory. He is obliged to unload everything into memory only when playing VMCLEAR.

As a result of the introduction of this level of indirection, the creators of future versions of VT-x will not be bound by the compatibility requirements of the VMCS layout in memory with existing implementations.

To compare this method with alternatives, look at how the operation of the XSAVE and XRSTOR instructions [1] used to save and restore vector registers is described. Since vector registers are stored in memory after saving, offsets for them can be used in normal operations with it. But for the layout of the fields in memory is described in a separate sheet of data returned by the CPUID instruction.

I will continue the story about the features of the VT-x, which surprised me with its thoughtfulness (not all the extensions of the instruction sets can be said about this). Many of these relate to identifying support for existing as well as future extensions of this technology.

Instead of putting VT-x information in the CPUID instruction output, new registers of the Model-specific register or MSR group were added. This is quite justified - MSRs can only be read from the privileged mode, user applications do not need to know about the features of supporting the virtualization of the current processor. The fact that virtualization is supported is reported by a single bit CPUID.1.ECX [5].

The description of the mechanism for indicating the supported VT-x extensions is covered in Appendix A of Intel SDM [1]. The possibility of evolution passes through all the MSRs presented in the documentation.

Thus, the register IA32_VMX_BASIC is divided into several fields. One of them contains a revision of the VMCS structure. Equality of revisions of two VMCS implementations means equality of sizes of memory areas for their storage. Bit 55 set in this register means that a number of configuration elements, which in the first VT-x edition had rigidly fixed values (only on or off), in this implementation can already be switched to a state other than the original.

The full list of MSRs describing capabilities includes the registers IA32_VMX_ (TRUE_) PINBASED_CTLS, IA32_VMX_ (TRUE_) PROCBASED_CTLS, IA32_VMX_PROCBSAED_CTLS2, IA32_VMX_ (TRUE_) EXIT_CTLS, IA32_VI In sum, they determine which architectural events can trigger a VM-exit, which is permissible to load at a VM-entry. Initially, the set of registers instituted in the first revision of the VT-x was not enough, so the TRUE variants of some of them appeared. For the same reason, PROCBASED_CTLS has been extended with PROCBASED_CTLS2.

Unlike the traditional approach, when each new feature gets one bit in the register, which means whether it is supported or not, the VT-x has two bits for each architecture extension. The first bit means the ability to enable some functionality, and the second - its off. This affects which bits in the control fields of the VMCS monitor can modify. For example, it may turn out that in some processors it will not be possible to turn off VT-exit generation according to the RDRAND instruction, while in others, on the contrary, such output cannot be turned on.

For those fields that can be in any of the two states, the monitor program is allowed to customize them to fit its capabilities and use only those that were embedded in its logic, even if the monitor is running on a more modern processor that offers more efficient techniques.

This solution creates space for the evolution of both processors and virtual machine monitor programs. The former can throw support for old features, simply denoting that they cannot be included, and the latter can detect and use only the functionality of the hardware for which they are programmed. This maintains backward compatibility and ensures forward compatibility.

Since so much effort has been spent on supporting VT-x extensions, there probably should be a lot of such extensions. I will talk about some of them in this article, and the rest will hold on for later, when the meaningfulness of their introduction becomes more understandable.

But first I want to think about the general vector of development of the VT-x - why all these extensions exist.

Virtualization must be effective, i.e. make the lowest possible overhead compared with the direct performance of the guest on the equipment. This is formulated as "not to interfere with the execution of as many operations as possible." The general principle of optimization is to accelerate first of all those subsystems that are on the critical path of performance. After eliminating the main bottleneck, you need to move on to the next in importance. Consider the order of importance for computing systems.

And what happened to the three processor modes that I described in the previous part of the article? As it turns out, their features also had to be taken into account during virtualization.

Protected mode with segmentation and page mechanism enabled is supported from the very first revision of the VT-x. Other modes, incl. 16-bit real, it was impossible to launch directly in non-root mode - an attempt to load such a guest state using VMLAUNCH / VMRESUME would return with failure. On the one hand, this restriction was reasonable - most of the practically important tasks work in protected mode, and it should be virtualized first.

On the other hand, when booting a traditional OS processor, before entering the protected mode, some time is still executed in other modes. To support them, the monitor had to have an alternative simulation mechanism — an interpreter, a binary translator, a return to VM86, or something like that. This did not have a positive effect either on the amount of monitor code or on the speed of its operation. Therefore, in subsequent VT-x generations, a so-called Unrestricted Guest mode - execution of guest systems that do not use protected mode.

While the root and non-root VT-x modes are running, the #SMI interrupt is still possible, which should unconditionally put the processor in SMM mode. The process of transitions to / from the SMM mode has been modified to take into account the specifics of virtualization.

In the simplest case, SMM login looks the same as it did without virtualization. However, you still have to save additional architectural state, including a pointer to the current VMCS, state of the SS.DPL field, RFLAGS.VM flag, STI and MOV SS locks, and virtual NMIs in the guest. As a result, the processor effectively interrupts the monitor and all virtual machines and cannot use the capabilities of the VT-x until it is released using the RSM instruction. This is not always convenient.

The VT-x extension, called Dual Monitor Treatment, allows the SMM monitor and the virtual machine monitor to cooperate with their work and use the modified VM-exit / entry mechanism to enter and exit the SMM. I will list here some features of this variant of work.

Thus, dual monitor facilitates the solution of the difficult question “who is in charge at home?”, Making the work of two monitors more coordinated and symmetrical.

At the moment, I hope that I managed to outline the motivation, main ideas and directions for the development of Intel VTx. Here I could finish my story, but ...

If some technology turns out to be successful, then rather quickly its users start coming up with completely unexpected ways for creators to use it, incl. "Wrong". It did not go around and virtualization. Virtual machines have replaced physical in many areas. They began to merge into the clouds, sell / rent. And the end users began to run their virtual machines inside the systems issued to them. And it turned out that such a scenario of nested virtualization was not initially provided by the creators of the hardware. What has been done to support the efficient operation of some virtual machines inside others on the Intel architecture is the next part of the article.

On CDTV: Launched under Ubuntu Linux, the Oracle VirtualBox program, which runs MS Windows XP, runs the Bochs simulator, which runs the FreeDOS operating system, which runs the MYZ80 simulator for the Z80 processor, which has the CP / CP loaded M (in full screen mode).

VT-x

In 2006, Intel introduced the VT-x, an extension for efficiently virtualizing the IA-32 architecture. It includes a set of VMX instructions and two new modes of operation. I do not want to repeat all the documentation here, it’s very boring to write as well as read. However, I will describe some features of the interfaces proposed in it.

')

It was impossible to manage to virtualize the already existing processor modes, since a number of IA-32 instructions that existed at that time were official, but not privileged, and, according to the theory , they could not be effectively intercepted and emulated. The new modes were called root and non-root, and they, in general, are orthogonal to all classical modes (although there are features here, see below). The first one is for the virtual machine monitor, the second one is for guest environments. By default, after power-up, virtualization is not available. Logging in to root mode occurs after the execution of the new VMXON instruction, and subsequent logins to non-root using VMLAUNCH / VMRESUME.

VMCS

The key process in any hardware virtualization system is saving the current state of the guest processor and loading the monitor state. In VT-x, everything here is done strictly according to the theory mentioned. An entity called VMCS (Virtual Machine Control Structure) is used to store the state of both the guest and the host. This structure should be different for each active guest. In the following figure, which illustrates transitions between root and non-root modes, two areas are used within VMCS: guest state (guest-state) and host state (host-state).

In this figure, the VM-Entry event is one of two instructions: VMLAUNCH or VMRESUME, and VM-Exit is one of the many synchronous and asynchronous events declared privileged in the context of non-root VT-x and therefore requiring monitor interception. Details of what and how to load when switching from root to non-root and back are also stored in the so-called VMCS. VM-entry and VM-exit controls, “entry and exit parameters”. The storage areas are divided into fields, each of which stores the register or other architectural information of the processor.

Work with VMCS

I want to show how carefully the creators of VT-x approached versioning and backward compatibility with future implementations. The key design element here is the amazing (considering its low level) abstractness of the proposed interface. Instead of describing the layout of the VMCS structure in memory and allowing it to work with conventional LOAD and STORE instructions, two new instructions were introduced: VMREAD and VMWRITE. And they do not operate with byte offsets within the structure, but with encodings of individual fields. Moreover, it is not even guaranteed that all fields in memory store actual values. The processor can cache some of them, thus speeding up the process of switching modes - data does not have to be loaded from slow memory. He is obliged to unload everything into memory only when playing VMCLEAR.

As a result of the introduction of this level of indirection, the creators of future versions of VT-x will not be bound by the compatibility requirements of the VMCS layout in memory with existing implementations.

To compare this method with alternatives, look at how the operation of the XSAVE and XRSTOR instructions [1] used to save and restore vector registers is described. Since vector registers are stored in memory after saving, offsets for them can be used in normal operations with it. But for the layout of the fields in memory is described in a separate sheet of data returned by the CPUID instruction.

Indication of available functionality

I will continue the story about the features of the VT-x, which surprised me with its thoughtfulness (not all the extensions of the instruction sets can be said about this). Many of these relate to identifying support for existing as well as future extensions of this technology.

Instead of putting VT-x information in the CPUID instruction output, new registers of the Model-specific register or MSR group were added. This is quite justified - MSRs can only be read from the privileged mode, user applications do not need to know about the features of supporting the virtualization of the current processor. The fact that virtualization is supported is reported by a single bit CPUID.1.ECX [5].

Versioning and display extensions

The description of the mechanism for indicating the supported VT-x extensions is covered in Appendix A of Intel SDM [1]. The possibility of evolution passes through all the MSRs presented in the documentation.

Thus, the register IA32_VMX_BASIC is divided into several fields. One of them contains a revision of the VMCS structure. Equality of revisions of two VMCS implementations means equality of sizes of memory areas for their storage. Bit 55 set in this register means that a number of configuration elements, which in the first VT-x edition had rigidly fixed values (only on or off), in this implementation can already be switched to a state other than the original.

The full list of MSRs describing capabilities includes the registers IA32_VMX_ (TRUE_) PINBASED_CTLS, IA32_VMX_ (TRUE_) PROCBASED_CTLS, IA32_VMX_PROCBSAED_CTLS2, IA32_VMX_ (TRUE_) EXIT_CTLS, IA32_VI In sum, they determine which architectural events can trigger a VM-exit, which is permissible to load at a VM-entry. Initially, the set of registers instituted in the first revision of the VT-x was not enough, so the TRUE variants of some of them appeared. For the same reason, PROCBASED_CTLS has been extended with PROCBASED_CTLS2.

Unlike the traditional approach, when each new feature gets one bit in the register, which means whether it is supported or not, the VT-x has two bits for each architecture extension. The first bit means the ability to enable some functionality, and the second - its off. This affects which bits in the control fields of the VMCS monitor can modify. For example, it may turn out that in some processors it will not be possible to turn off VT-exit generation according to the RDRAND instruction, while in others, on the contrary, such output cannot be turned on.

For those fields that can be in any of the two states, the monitor program is allowed to customize them to fit its capabilities and use only those that were embedded in its logic, even if the monitor is running on a more modern processor that offers more efficient techniques.

This solution creates space for the evolution of both processors and virtual machine monitor programs. The former can throw support for old features, simply denoting that they cannot be included, and the latter can detect and use only the functionality of the hardware for which they are programmed. This maintains backward compatibility and ensures forward compatibility.

VT-x Evolution

Since so much effort has been spent on supporting VT-x extensions, there probably should be a lot of such extensions. I will talk about some of them in this article, and the rest will hold on for later, when the meaningfulness of their introduction becomes more understandable.

But first I want to think about the general vector of development of the VT-x - why all these extensions exist.

Virtualization must be effective, i.e. make the lowest possible overhead compared with the direct performance of the guest on the equipment. This is formulated as "not to interfere with the execution of as many operations as possible." The general principle of optimization is to accelerate first of all those subsystems that are on the critical path of performance. After eliminating the main bottleneck, you need to move on to the next in importance. Consider the order of importance for computing systems.

- CPU instructions. The most important resource is the CPU, and the very first version of the VT-x was used to execute most instructions without slowing down. Subsequent improvements in this direction were aimed at ensuring that even fewer instructions call the VM-exit, as well as all processor modes to be virtualized (see the sections on Unrestricted Guest and SMM later in this article).

- Work with memory. Here, a frequent but potentially slow operation is the translation of linear addresses into physical ones. Its details and solution are described in my previous article, so I will not repeat. In IA-32, the corresponding extension is called Intel EPT (English Extended Page Translation), and it works according to theory. A resource such as TLB also required virtualization, and it was provided with the introduction of VPID, a technique for associating its entries with individual guests.

- Virtual APIC (English Advanced Programmable Interrupt Controller). The interrupt controller can be a bottleneck in monitor performance, as the load on it increases with the number of simultaneously running virtual machines (and the interrupt rate in the system). Therefore, several VT-x extensions were made for APIC functions virtualization: virtual memory page for APIC registers, TPR shadow, CR8 load exiting, virtualize x2APIC mode.

- Peripheral devices that require high bandwidth for their work, for example, graphics accelerators. For these devices, it is required to efficiently convert addresses in memory for DMA, as well as handle interrupts, in both cases doing this with minimal participation of the monitor. For this functionality, it is no longer the Intel VT-x specification that is responsible, but Intel VT-d [2].

And what happened to the three processor modes that I described in the previous part of the article? As it turns out, their features also had to be taken into account during virtualization.

Unrestricted guest

Protected mode with segmentation and page mechanism enabled is supported from the very first revision of the VT-x. Other modes, incl. 16-bit real, it was impossible to launch directly in non-root mode - an attempt to load such a guest state using VMLAUNCH / VMRESUME would return with failure. On the one hand, this restriction was reasonable - most of the practically important tasks work in protected mode, and it should be virtualized first.

On the other hand, when booting a traditional OS processor, before entering the protected mode, some time is still executed in other modes. To support them, the monitor had to have an alternative simulation mechanism — an interpreter, a binary translator, a return to VM86, or something like that. This did not have a positive effect either on the amount of monitor code or on the speed of its operation. Therefore, in subsequent VT-x generations, a so-called Unrestricted Guest mode - execution of guest systems that do not use protected mode.

Interaction with SMM

While the root and non-root VT-x modes are running, the #SMI interrupt is still possible, which should unconditionally put the processor in SMM mode. The process of transitions to / from the SMM mode has been modified to take into account the specifics of virtualization.

In the simplest case, SMM login looks the same as it did without virtualization. However, you still have to save additional architectural state, including a pointer to the current VMCS, state of the SS.DPL field, RFLAGS.VM flag, STI and MOV SS locks, and virtual NMIs in the guest. As a result, the processor effectively interrupts the monitor and all virtual machines and cannot use the capabilities of the VT-x until it is released using the RSM instruction. This is not always convenient.

The VT-x extension, called Dual Monitor Treatment, allows the SMM monitor and the virtual machine monitor to cooperate with their work and use the modified VM-exit / entry mechanism to enter and exit the SMM. I will list here some features of this variant of work.

- During the transition to SMM, there is a special type of VM-exit, called the SMM VM exit. The processes that occur during this have some differences from ordinary VM-exit events.

- SMM VM exit is the only type of exit that can happen inside the root mode , i.e. while running the virtual machine monitor. Regular VM-exit can happen only when the guests are working.

- A separate VMCS is allocated for storing state and managing SMM VM-exit transitions.

- If in the classic case, the RSM instruction was used to terminate work in the SMM mode, then when virtualization is enabled, this is done using the usual VM-entry, which is returned either to the monitor (if the output was from the root mode), or to the guest environment (in non- root)

- Logging into SMM is possible explicitly from root-mode, using the VMCALL instruction, and not just on the #SMI interrupt.

Thus, dual monitor facilitates the solution of the difficult question “who is in charge at home?”, Making the work of two monitors more coordinated and symmetrical.

At the moment, I hope that I managed to outline the motivation, main ideas and directions for the development of Intel VTx. Here I could finish my story, but ...

To be continued

If some technology turns out to be successful, then rather quickly its users start coming up with completely unexpected ways for creators to use it, incl. "Wrong". It did not go around and virtualization. Virtual machines have replaced physical in many areas. They began to merge into the clouds, sell / rent. And the end users began to run their virtual machines inside the systems issued to them. And it turned out that such a scenario of nested virtualization was not initially provided by the creators of the hardware. What has been done to support the efficient operation of some virtual machines inside others on the Intel architecture is the next part of the article.

Literature

- Intel Corporation. Intel 64 and IA-32 Architects Software Developer's Manual. Volumes 1-3, 2014. www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/processors/architectures-software-developer-manuals.html

- Intel Corporation. Intel Virtualization Technology for Directed I / O Architecture Specification. 2013. www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/intelligent-systems/intel-technology/vt-directed-io-spec.html

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/237523/

All Articles