Medical anatomical illustration - the history of the study of the human body in the atlases of 5 centuries. Part 1

We continue the story of biomedical and anatomical illustration , which became one of the first methods of man’s knowledge of the structure of his own body several centuries ago, and later became the most powerful tool for the transfer of accumulated knowledge. In the next two weeks, we will talk about different periods in the history of anatomy through atlases, drawings by great artists, wax models, photos of embalmed bodies, frozen and chopped into micron layers, and up to the iPad applications of our days. Let's go, today is the 15th century and later the Renaissance - the works of Galen become obsolete, scientists, philosophers and artists come to the ideas of humanism, and the church reconsiders its views on the autopsy and study of human corpses.

Revival, Anatomy and Church

Prerequisites for the development of anatomy and anatomical patterns in Europe and, above all, in Italy, appeared at the end of the Renaissance. Up to this point, both the study of the human body and the range of topics available to artists were significantly limited by the authority of the church. Anatomy was stagnant - doctors usually did not go beyond dogmas known since Galen’s time. Individual physicians, for example, Mondino de Luzzi in Bologna, were engaged in research and described methods of human anatomy, but this was not a system.

Since the Renaissance, people's views have changed a lot. Accents have shifted towards a comprehensive study of man, all divine has begun to attract less attention.

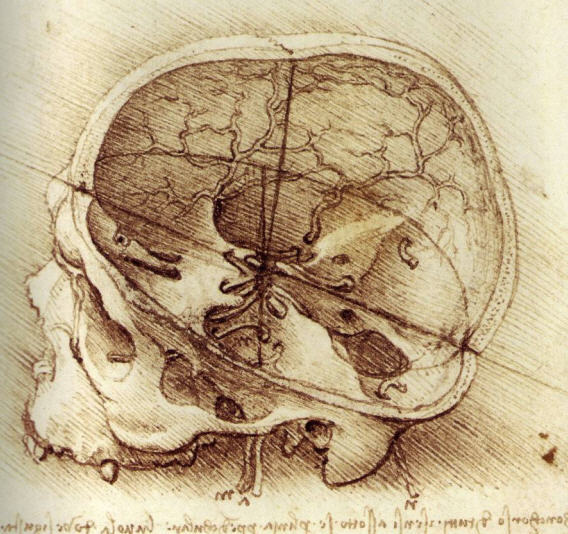

The development of anatomical science was facilitated by the formal disposition of Pope Sixt IV of 1472, which allowed anatomists to reveal human corpses for scientific and educational purposes, if they belonged, for example, to executed criminals. There was a growing understanding that anatomy is important for the treatment of diseases. On the other hand, at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, painting came to the point that you can make images more realistic, use perspective and three-dimensional composition, moving away from the medieval understanding of portraits as something symbolic. Artists began to be interested in harmonious proportions of the body - many painters began to study them, including Michelangelo, who painted the Sistine Chapel, named just after the Pope, Leonardo da Vinci or Albrecht Durer, who even created illustrated scientific works on this topic . Artists were less interested in the internal structure of the organism, but scientists began to realize that the study of anatomy can be significantly accelerated if the description of organs is supplemented with illustrations and diagrams. According to some information, the anatomist Marcantonio della Torre planned to create one of the first anatomical atlases, inviting Leonardo as an illustrator, but the scientist died of the plague, before he could finish the work. Only a part of da Vinci's anatomical drawings reached us.

')

Anatomical drawing of Leonardo. Human skull with a cut fragment. It can be seen that Leonardo was attentive to details: the seam between the frontal and parietal bone is shown, the texture of the spongy substance on the cut is visible. General outlines are transmitted with great accuracy.

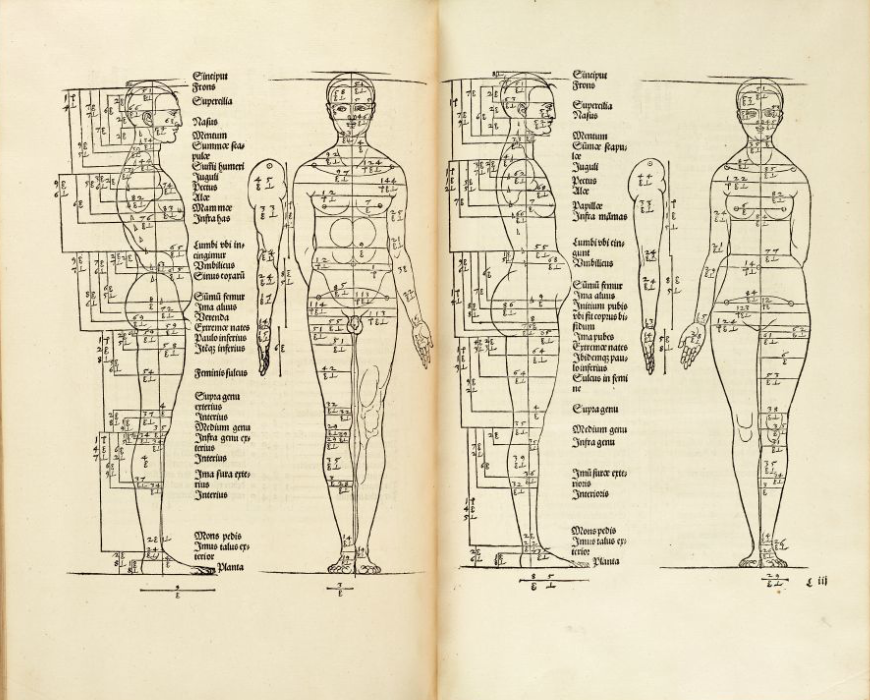

Anatomical drawing of Michelangelo. You can see how the artist noted the lengths of individual parts of the body and their correlation ( source )

Diagram of the proportions of a man by Albrecht Dürer ( source ). Compared to the Italians, the realistic image is lower, but also visible, as the proportions of the limbs and their parts were noted.

XVI century: from the domination of Galen to rethinking anatomy

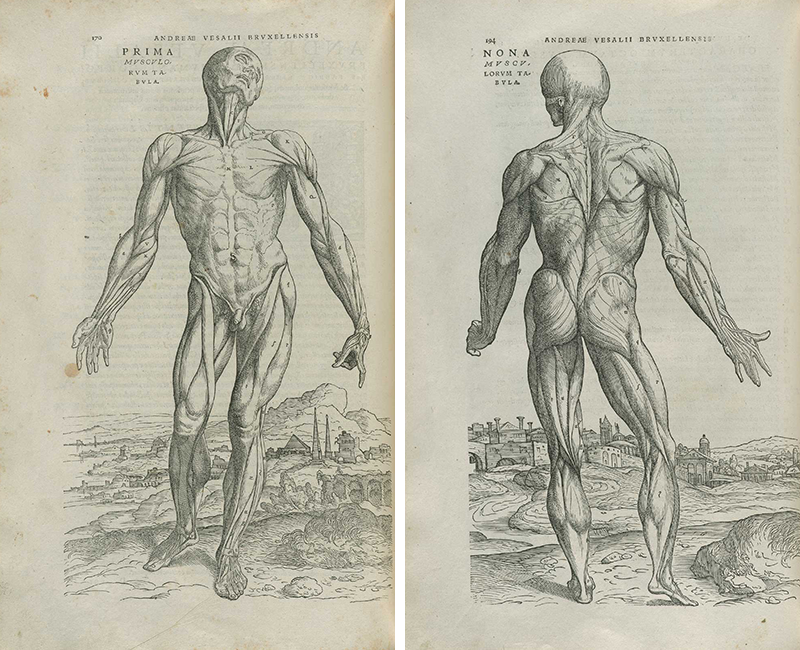

The sixteenth century was revolutionary for anatomy and medical illustration. In part, the head of the church also contributed to this — Pope Clement VII approved the teaching of this subject. But the central figure of the "anatomical revolution" became Andreas Vesalius ( Andreas Vesalius ) - a scientist who was born in 1514 in Brussels, which then belonged to the Netherlands. After studying at the University of the Netherlands and at the Sorbonne, Vesalius finds himself in Padua, where he quickly becomes a professor at a prestigious local university. Vesalius actively advocated the use of real human bodies in the training of anatomists and physicians, which was not so accepted before, since Western medicine of the time relied mainly on texts and illustrations of Galen, who lived thirteen centuries earlier, and restrictions on working with human corpses were removed not long ago. During the autopsies, Andreas Vesalius made sketches, the accuracy and quality of which the students soon appreciated, and began to replicate them. This activity in 1543 developed into the creation of a real atlas called De humani corporis fabrica , in which there were 7 volumes. It is curious that during his activities Vesalius found many mistakes in Galen's works (for example, he pointed out that there are no holes between the ventricles of the heart, and the lower jaw is one and not two bones). This is easily explained, since Galen worked primarily with magnets - the only monkeys living in Europe, whose anatomy is still significantly different from human, despite the evolutionary kinship.

Some historians are convinced that Jan van Kalkar , one of Titian's students, could help Vesalius in creating the atlas and carved anatomical engravings (woodcuts). In total, there were 273 anatomical drawings in the atlas. The book Vesalius was printed by Johannes Oporin ( Johannes Oporinus ).

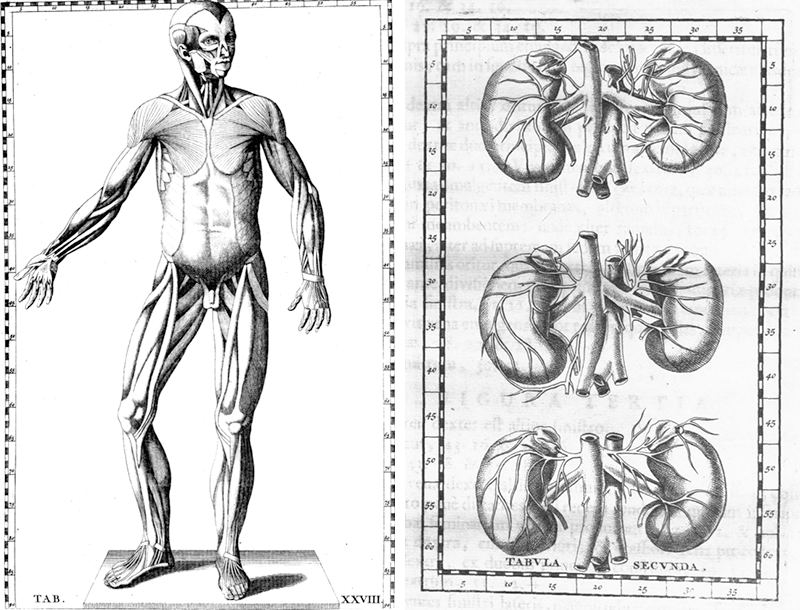

Illustrations from the book Vesalius ( source ). Under the link you can find many more images. It can be seen that the bodies in the illustrations are presented in “artistic” poses, but at the same time, individual muscles, bones or vessels are shown in numbers and signatures. Apparently, the autopsy technique itself meant bending out certain tissue fragments without completely removing them.

For comparison - the picture of van Kalkar "Melchior von Brauweiler", written in 1540. The graphics in the atlases of Vesalius are much more modest in design, but for replicating anatomical tables it was necessary to cut the design on a wooden plate, which, of course, affected the quality.

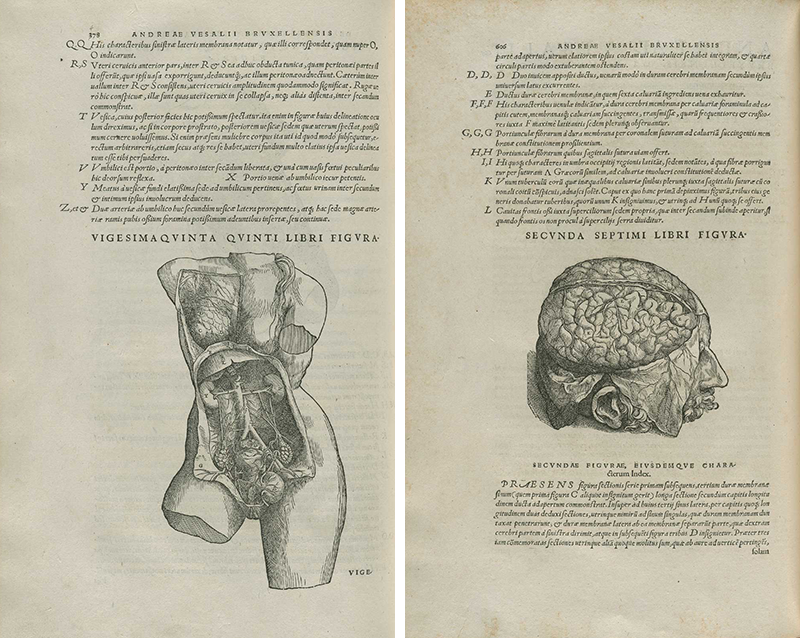

In addition to Vesalius, the 16th century is marked by the works of Gabriele Falloppio ( Falloppius ) and Bartolomeo Eustachi ( Eustachius ). Fallopio was a pupil and friend of Vesalius and was also a professor at the University of Padua for some time. Eustache, in contrast, was an apologist for Galen's anatomy and at first largely disagreed with representatives of the Vesalius school. A little later, Vesalius, in 1552, he, along with his assistants Pierre Matteo Pini and Giulio de Musey, also completed work on the Anatomical Tables , which included 47 plates and were replicated only in 1714 . The work of these scientists was reflected in the anatomical nomenclature of the fallopian and Eustachian tubes, but their work affected the anatomy of all organs and systems of the body and greatly changed ideas about the structure of the human body. Evssahi, by the way, was the first to describe the structure of the bones and muscles of the inner ear.

Illustrations from the Atlas of Eustache. The style is reminiscent of works from the atlases of Vesalius, although it looks somewhat simpler. It can be seen that the detailing is not yet high, and there are not very many signatures. The terminology of muscles, bones, blood vessels, nerves and other organs is still in its early stages of development. The arrangement of the vessels of the kidneys is not quite true.

Biblioteca Centrale Biomedica, Cagliari

Interestingly, among the anatomical and medical books of that time, textbooks on general and even plastic surgery came across. We can give an example of the books of Johannes de Vigo or Gaspare Tagliacozzi . However, there were almost no illustrations in their works.

In addition to Vesalius and his already mentioned students and colleagues, we can recall several other names and examples of anatomical illustrations of the XVI century. Part can be found on this link . Of the other, lesser-known anatomists of that time, Volkher Koiter and Guido Guidi deserve attention. Both were followers of the Italian school, but Koiter lived most of his life as a doctor in Nuremberg and was known as a researcher of comparative osteology. Guidi worked and taught in France. One of his notable works was the manual on surgery . The vidian nerve (n. Vidii) and the vidian artery (arteria Vidiana) are named after this researcher.

This can be completed with the XVI century, which prepared an excellent ground for the further development of anatomy and anatomical illustration. In the next post we will continue to talk about anatomists from Padua, touch on the topic of anatomical wax models, as well as get to Peter the Great, his Dutch friends and their contribution to the domestic anatomy and medicine. And next week we will reach the atlases of pathologies, Gray's anatomy, amazing and controversial works of German illustrators of the 20th century and tell you what thoughts the best modern contemporary atlases and interactive applications shared with us about the development of this area.

Other posts in the series:

Part two

Part three

Conclusion

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/233787/

All Articles