Trisection angle and other tasks on the construction

On Habré there was an article where the author built a trisection of a corner. In this post, I will explain why it is impossible to precisely divide an arbitrary flat angle into three equal parts with a compass and a ruler, along the way I will give a brief introduction to algebraic field theory, and show how this can be applied to other well-known construction problems.

The famous task of trisection of an arbitrary angle with a compass and a ruler without divisions is one of the oldest problems that has attracted many mathematicians for several millennia. The unsolvability of the problem, i.e. the impossibility of such a construction was finally proved in the 19th century, but some people still offer their solutions. For example, the decision of one academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences was published in the journal Science and Life. Although, maybe this is such a subtle trolling ...

')

True, according to one professor of mathematics, the flow of letters with solutions to the trisection of the angle and simple proofs of Fermat's great theorem has recently decreased markedly. Now he is sent, as a rule, evidence of the Riemann hypothesis .

In essence, a field is a set of elements with zero that can be added, subtracted, multiplied and divided (except division by zero) among themselves, and the result of such operations is always uniquely defined and also an element of this field. In addition, as for arithmetic operations with real numbers, in the fields you can interchange the terms / factors and expand the brackets without changing the result.

The set of real numbers R is just the simplest example of a field. For any arithmetic operations with such numbers (except for division by zero) the result is a real number. A similar example is the field of complex numbers C.

The field of rational numbers Q is the set of fractions m / n for integers m, n. It is easy to see that when adding / multiplying / dividing fractions a fraction is obtained, therefore Q is a field.

The set of integers Z, on the contrary, is not a field, since the division does not always give an integer: 5/7 is not an integer, therefore it is not included in Z.

Separately, it should be noted finite fields, or Galois fields - fields with a finite number of elements. For a prime p, the field F p can be represented as a set of p numbers {0,1, ..., p-1}, in which arithmetic operations are performed modulo p. For example, in the field F 5 : 2 + 3 = 5 mod 5 = 0. 2 * 3 = 6 mod 5 = 1 and therefore 1/3 = (2 * 3) / 3 = 2, etc. Finite fields are often used in algebraic error-correcting codes and cryptography: Reed-Solomon codes, AES, and elliptic cryptography operate in finite fields.

The field L is an extension of the field K and is denoted L / K if L entirely contains K, and the operations in L and K act the same. For example, the field R is an extension of the R / Q field of rational numbers Q, and the field of complex numbers C is an extension C / R of the field R.

Consider an arbitrary field K and a set K [x] of all polynomials in a variable x with coefficients from K. A polynomial p (x) from K [x] is called irreducible over the field K if it is indecomposable by (non-constant) factors from K [x]. For example, the polynomial P (x) = x 2 +1 is irreducible over R, but we give over C, since decomposed into factors of C [x]: x 2 + 1 = (xi) (x + i).

We will be interested in such extensions L / K of the field K, which can be constructed by adding to K some element w (included in L, but not in K) and all possible expressions with w and with elements from K. Then the field extension will be denoted as: L / K = K (w). If the element w is a root of some irreducible polynomial p (x) of degree d from K [x] (that is, p (w) = 0), then we write L / K = K (w) = K [x] / ( p (x)) and say that L is an extension of the degree [L: K] = d , and w has degree d over the field K. In this case, the extension L / K can be represented as a set of polynomials with coefficients from K modulo the polynomial p (x), i.e. sets of polynomials of degree lower than d. The extensions L / K of the first degree are equal to the initial field L = K, i.e. in fact, do not expand the field K.

Returning to the example of the field of complex numbers: C = C / R can be obtained from R by attaching an imaginary unit C / R = R (i); while i is a root of an irreducible over R polynomial x 2 +1 (since i 2 + 1 = 0) of the second degree, then C = C / R = R [x] / (x 2 +1) is an extension of degree 2, and is representable in the form of a set of polynomials of the first and zero degrees with coefficients from R, in which operations are performed modulo x 2 +1. Or equivalently

C / R = R (i); while i is a root of an irreducible over R polynomial x 2 +1 (since i 2 + 1 = 0) of the second degree, then C = C / R = R [x] / (x 2 +1) is an extension of degree 2, and is representable in the form of a set of polynomials of the first and zero degrees with coefficients from R, in which operations are performed modulo x 2 +1. Or equivalently  .

.

Uff. With a hard theory done, further light and fun practice begins.

Now let's ask ourselves what can and what cannot be built with a compass and a ruler?

Any such construction begins with some two points given to us on a plane defining a single segment. We consider these points constructed . Having two constructed points, we can either draw a straight line through them, or create a circle with a compass with a center in one of them and passing through the other. These lines and circles will also be called constructed. The intersection of the constructed lines and circles gives new constructed points through which you can draw new lines and circles, and so on. This exhausts operations with compasses and ruler without divisions. Points and lines are achievable if they can be constructed through a finite number of similar operations.

We introduce a Cartesian coordinate system 0xy, in which the original two points have coordinates (0,0) and (1,0). Suppose the numbers a, b, c, d, a ', b', c ', d' belong to the field K. It can be shown that the lines constructed at points with such coordinates intersect at points with coordinates in the field L, such that [L: K] ≤2.

Thus, when adding a new line to our drawing, the coordinates of the newly constructed points lie in the current field K or in its extension L / K of degree 2. When constructing the same circles on points from L / K, an extension of the field L / K is formed: E / L, [E: L] = 2. The degrees of successive extensions are multiplied, that is, E is an extension of E / K of a field K of degree [E: K] = [E: L] [L: K] = 2 * 2 = 2 2 . This means that all reachable points have coordinates from the extension of the field K only degrees 2 n . The construction of the point (a, b) is equivalent to the construction of the points (a, 0), (b, 0), so in the following we will simply say “build a segment of length a” or “build number b”.

Let us be given a pair of lines intersecting at an angle ξ at the point (0,0). Together with our other starting point (1,0), specifying an angle is equivalent to specifying a segment of length cos ξ, that is, we start building with numbers in the field Q (cos ξ). In turn, the construction of the angle ξ / 3 is equivalent to the construction of a segment of length cos (ξ / 3). The trigonometric identity cos ξ = 4cos 3 (ξ / 3) -3cos (ξ / 3) shows that we need to construct (segment of length c) the root of the polynomial p (x) = 4x 3 -3x-cos ξ, starting with the points with coordinates in the field Q (cos ξ) . However, for almost all angles ξ, this polynomial is irreducible over the field Q (cos ξ). For example, in the case of ξ = 60 ° cos ξ = 1/2, the polynomial p (x) = 4x 3 -3x-1/2 does not decompose into factors over the field Q (cos ξ) = Q (1/2) = Q. Since cos (ξ / 3) lies in the extension Q (cos (ξ / 3)) = Q [x] / (p (x)) of the field Q (cos ξ), and this extension in the case of irreducible p (x) has the degree the polynomial p (x), that is, 3 ≠ 2 n , then cos (ξ / 3) is not an attainable length of a segment or a coordinate of a point. Therefore, in these cases exact trisection of the angle is impossible.

Of course, there are angles that allow for trisection. For example, it is easy to build an angle of 30 °, having (and even not having) an angle of ξ = 90 °. In this case, the polynomial p (x) = 4x 3 -3x-cos ξ = 4x 3 -3x = x (4x 2 -3) decomposes into factors in Q (cos ξ) = Q; the irreducible polynomial for cos 30 ° is 4x 2 -3, the extension Q (cos (ξ / 3)) = Q ( ) has degree 2 over Q, and its elements are easily reachable with a compass and a ruler. But such good angles are negligible.

) has degree 2 over Q, and its elements are easily reachable with a compass and a ruler. But such good angles are negligible.

A similar approach is also used in the evidence (non) possibilities of other geometric constructions with compass and ruler:

I hope that I was not too tired of my dear readers with an abundance of calculations and was able on such a simple example to demonstrate the beauty and close interconnectedness of different sections of mathematics. I will be glad to see comments and comments.

Introduction

The famous task of trisection of an arbitrary angle with a compass and a ruler without divisions is one of the oldest problems that has attracted many mathematicians for several millennia. The unsolvability of the problem, i.e. the impossibility of such a construction was finally proved in the 19th century, but some people still offer their solutions. For example, the decision of one academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences was published in the journal Science and Life. Although, maybe this is such a subtle trolling ...

Science and Life, №3, 1998

')

True, according to one professor of mathematics, the flow of letters with solutions to the trisection of the angle and simple proofs of Fermat's great theorem has recently decreased markedly. Now he is sent, as a rule, evidence of the Riemann hypothesis .

Fields

In essence, a field is a set of elements with zero that can be added, subtracted, multiplied and divided (except division by zero) among themselves, and the result of such operations is always uniquely defined and also an element of this field. In addition, as for arithmetic operations with real numbers, in the fields you can interchange the terms / factors and expand the brackets without changing the result.

The set of real numbers R is just the simplest example of a field. For any arithmetic operations with such numbers (except for division by zero) the result is a real number. A similar example is the field of complex numbers C.

The field of rational numbers Q is the set of fractions m / n for integers m, n. It is easy to see that when adding / multiplying / dividing fractions a fraction is obtained, therefore Q is a field.

The set of integers Z, on the contrary, is not a field, since the division does not always give an integer: 5/7 is not an integer, therefore it is not included in Z.

Separately, it should be noted finite fields, or Galois fields - fields with a finite number of elements. For a prime p, the field F p can be represented as a set of p numbers {0,1, ..., p-1}, in which arithmetic operations are performed modulo p. For example, in the field F 5 : 2 + 3 = 5 mod 5 = 0. 2 * 3 = 6 mod 5 = 1 and therefore 1/3 = (2 * 3) / 3 = 2, etc. Finite fields are often used in algebraic error-correcting codes and cryptography: Reed-Solomon codes, AES, and elliptic cryptography operate in finite fields.

Field extension

The field L is an extension of the field K and is denoted L / K if L entirely contains K, and the operations in L and K act the same. For example, the field R is an extension of the R / Q field of rational numbers Q, and the field of complex numbers C is an extension C / R of the field R.

Consider an arbitrary field K and a set K [x] of all polynomials in a variable x with coefficients from K. A polynomial p (x) from K [x] is called irreducible over the field K if it is indecomposable by (non-constant) factors from K [x]. For example, the polynomial P (x) = x 2 +1 is irreducible over R, but we give over C, since decomposed into factors of C [x]: x 2 + 1 = (xi) (x + i).

We will be interested in such extensions L / K of the field K, which can be constructed by adding to K some element w (included in L, but not in K) and all possible expressions with w and with elements from K. Then the field extension will be denoted as: L / K = K (w). If the element w is a root of some irreducible polynomial p (x) of degree d from K [x] (that is, p (w) = 0), then we write L / K = K (w) = K [x] / ( p (x)) and say that L is an extension of the degree [L: K] = d , and w has degree d over the field K. In this case, the extension L / K can be represented as a set of polynomials with coefficients from K modulo the polynomial p (x), i.e. sets of polynomials of degree lower than d. The extensions L / K of the first degree are equal to the initial field L = K, i.e. in fact, do not expand the field K.

Returning to the example of the field of complex numbers: C = C / R can be obtained from R by attaching an imaginary unit

C / R = R (i); while i is a root of an irreducible over R polynomial x 2 +1 (since i 2 + 1 = 0) of the second degree, then C = C / R = R [x] / (x 2 +1) is an extension of degree 2, and is representable in the form of a set of polynomials of the first and zero degrees with coefficients from R, in which operations are performed modulo x 2 +1. Or equivalently

C / R = R (i); while i is a root of an irreducible over R polynomial x 2 +1 (since i 2 + 1 = 0) of the second degree, then C = C / R = R [x] / (x 2 +1) is an extension of degree 2, and is representable in the form of a set of polynomials of the first and zero degrees with coefficients from R, in which operations are performed modulo x 2 +1. Or equivalently  .

.Uff. With a hard theory done, further light and fun practice begins.

Building with compass and ruler

Now let's ask ourselves what can and what cannot be built with a compass and a ruler?

Any such construction begins with some two points given to us on a plane defining a single segment. We consider these points constructed . Having two constructed points, we can either draw a straight line through them, or create a circle with a compass with a center in one of them and passing through the other. These lines and circles will also be called constructed. The intersection of the constructed lines and circles gives new constructed points through which you can draw new lines and circles, and so on. This exhausts operations with compasses and ruler without divisions. Points and lines are achievable if they can be constructed through a finite number of similar operations.

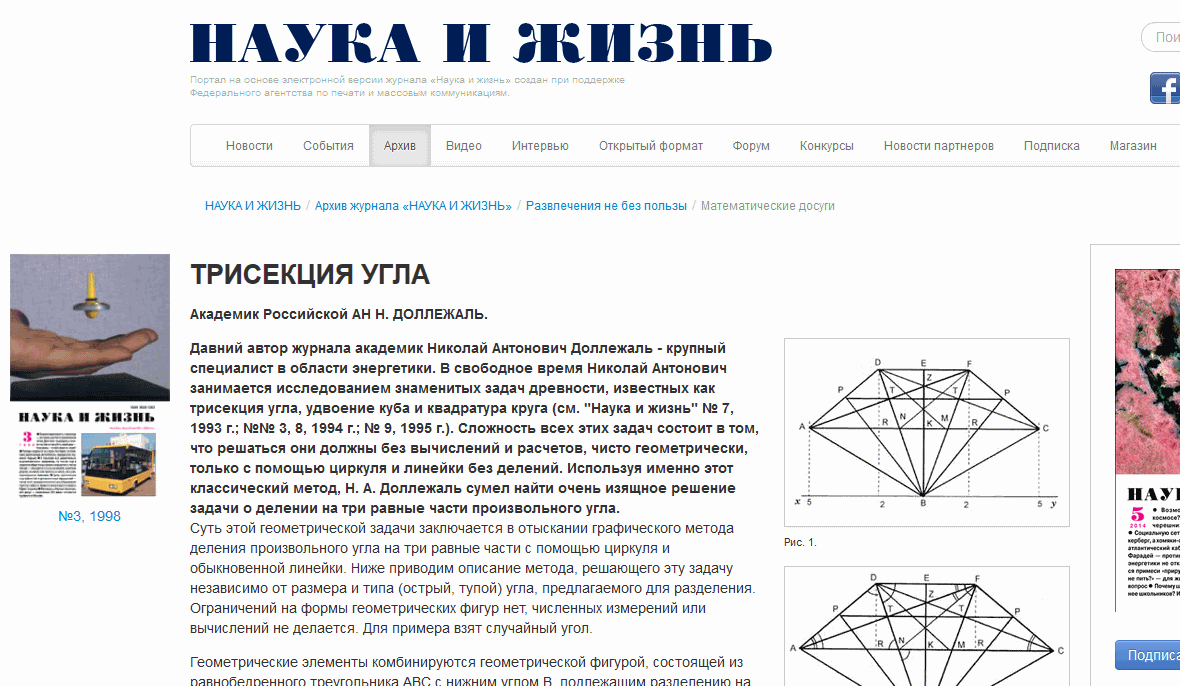

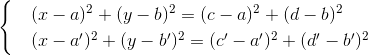

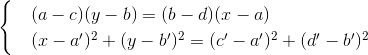

We introduce a Cartesian coordinate system 0xy, in which the original two points have coordinates (0,0) and (1,0). Suppose the numbers a, b, c, d, a ', b', c ', d' belong to the field K. It can be shown that the lines constructed at points with such coordinates intersect at points with coordinates in the field L, such that [L: K] ≤2.

need to show

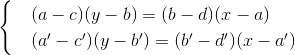

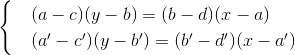

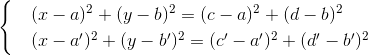

The straight line passing through the points (a, b), (c, d) is given by the equation (ac) (yb) = (bd) (xa). The equation of a circle with center (a, b) passing through (c, d) is given by (xa) 2 + (yb) 2 = (ca) 2 + (db) 2 . The coefficients of the equations of lines and circles constructed by two pairs of points (a, b), (c, d), and (a ', b'), (c ', d') are also in K. The coordinates of the intersection point of two such lines are by solving a linear system

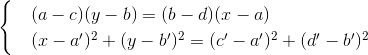

The solution is expressed by the relationship of some linear functions of the coefficients of the equations, that is, (x, y) also belongs to K. The coordinates of the intersection point of the line and the circle are taken from the system

Expressing x through y from the first equation, substituting and excluding x in the second, we get a quadratic equation for y with coefficients from K. The solution is expressed in terms of a linear combination of the coefficients and the root from discriminant D equation. The root is not necessarily an element of K, but an element of the extension

from discriminant D equation. The root is not necessarily an element of K, but an element of the extension  . If D is not a complete square in K, then we have an extension of the second degree, since

. If D is not a complete square in K, then we have an extension of the second degree, since  is the root of an irreducible polynomial

is the root of an irreducible polynomial  . Similar reasoning for x gives

. Similar reasoning for x gives  . If the discriminant is negative, then the solutions are imaginary, the circle with the line does not intersect, and no new points are formed.

. If the discriminant is negative, then the solutions are imaginary, the circle with the line does not intersect, and no new points are formed.

Finally, to intersect two circles

subtract from the other equation another, reducing x 2 , y 2 and getting linear in x, y equation. We add a new equation to the system, and again we come to the case of the intersection of the line and the circle, in which .

.

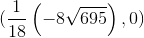

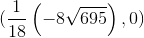

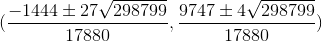

Let us demonstrate these calculations with an example (a, b) = (0,0), (c, d) = (1,0), (a ', b') = (- 4 / 9.3), (c ', d ') = (1 / 3,1 / 2) with coordinates from Q. The intersections of two lines, a line with a circle, two circles, built on these four points, have coordinates

(x 0 , y 0 ) = (22 / 45.0),

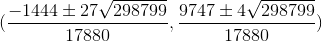

(x 1 , y 1 ) = ,

,

(x 2 , y 2 ) = ,

,

respectively. It can be seen that x 0 , y 0 ∈Q, the line with the circle does not intersect, and x 2 , y 2 .

.

The solution is expressed by the relationship of some linear functions of the coefficients of the equations, that is, (x, y) also belongs to K. The coordinates of the intersection point of the line and the circle are taken from the system

Expressing x through y from the first equation, substituting and excluding x in the second, we get a quadratic equation for y with coefficients from K. The solution is expressed in terms of a linear combination of the coefficients and the root

from discriminant D equation. The root is not necessarily an element of K, but an element of the extension

from discriminant D equation. The root is not necessarily an element of K, but an element of the extension  . If D is not a complete square in K, then we have an extension of the second degree, since

. If D is not a complete square in K, then we have an extension of the second degree, since  is the root of an irreducible polynomial

is the root of an irreducible polynomial  . Similar reasoning for x gives

. Similar reasoning for x gives  . If the discriminant is negative, then the solutions are imaginary, the circle with the line does not intersect, and no new points are formed.

. If the discriminant is negative, then the solutions are imaginary, the circle with the line does not intersect, and no new points are formed.Finally, to intersect two circles

subtract from the other equation another, reducing x 2 , y 2 and getting linear in x, y equation. We add a new equation to the system, and again we come to the case of the intersection of the line and the circle, in which

.

.Let us demonstrate these calculations with an example (a, b) = (0,0), (c, d) = (1,0), (a ', b') = (- 4 / 9.3), (c ', d ') = (1 / 3,1 / 2) with coordinates from Q. The intersections of two lines, a line with a circle, two circles, built on these four points, have coordinates

(x 0 , y 0 ) = (22 / 45.0),

(x 1 , y 1 ) =

,

,(x 2 , y 2 ) =

,

,respectively. It can be seen that x 0 , y 0 ∈Q, the line with the circle does not intersect, and x 2 , y 2

.

.Thus, when adding a new line to our drawing, the coordinates of the newly constructed points lie in the current field K or in its extension L / K of degree 2. When constructing the same circles on points from L / K, an extension of the field L / K is formed: E / L, [E: L] = 2. The degrees of successive extensions are multiplied, that is, E is an extension of E / K of a field K of degree [E: K] = [E: L] [L: K] = 2 * 2 = 2 2 . This means that all reachable points have coordinates from the extension of the field K only degrees 2 n . The construction of the point (a, b) is equivalent to the construction of the points (a, 0), (b, 0), so in the following we will simply say “build a segment of length a” or “build number b”.

Corner trisection

Let us be given a pair of lines intersecting at an angle ξ at the point (0,0). Together with our other starting point (1,0), specifying an angle is equivalent to specifying a segment of length cos ξ, that is, we start building with numbers in the field Q (cos ξ). In turn, the construction of the angle ξ / 3 is equivalent to the construction of a segment of length cos (ξ / 3). The trigonometric identity cos ξ = 4cos 3 (ξ / 3) -3cos (ξ / 3) shows that we need to construct (segment of length c) the root of the polynomial p (x) = 4x 3 -3x-cos ξ, starting with the points with coordinates in the field Q (cos ξ) . However, for almost all angles ξ, this polynomial is irreducible over the field Q (cos ξ). For example, in the case of ξ = 60 ° cos ξ = 1/2, the polynomial p (x) = 4x 3 -3x-1/2 does not decompose into factors over the field Q (cos ξ) = Q (1/2) = Q. Since cos (ξ / 3) lies in the extension Q (cos (ξ / 3)) = Q [x] / (p (x)) of the field Q (cos ξ), and this extension in the case of irreducible p (x) has the degree the polynomial p (x), that is, 3 ≠ 2 n , then cos (ξ / 3) is not an attainable length of a segment or a coordinate of a point. Therefore, in these cases exact trisection of the angle is impossible.

Of course, there are angles that allow for trisection. For example, it is easy to build an angle of 30 °, having (and even not having) an angle of ξ = 90 °. In this case, the polynomial p (x) = 4x 3 -3x-cos ξ = 4x 3 -3x = x (4x 2 -3) decomposes into factors in Q (cos ξ) = Q; the irreducible polynomial for cos 30 ° is 4x 2 -3, the extension Q (cos (ξ / 3)) = Q (

) has degree 2 over Q, and its elements are easily reachable with a compass and a ruler. But such good angles are negligible.

) has degree 2 over Q, and its elements are easily reachable with a compass and a ruler. But such good angles are negligible.Conclusion

A similar approach is also used in the evidence (non) possibilities of other geometric constructions with compass and ruler:

- The problem of doubling a cube - another unsolvable problem of antiquity - is to construct a cube edge with a compass and a ruler, the volume of which is twice the size of a given cube, i.e. in plotting a length of

with this unit segment. It is easy to see that b is a root of an irreducible over Q polynomial x 3 -2, has degree 3 2 n over Q, and, therefore, is unattainable.

with this unit segment. It is easy to see that b is a root of an irreducible over Q polynomial x 3 -2, has degree 3 2 n over Q, and, therefore, is unattainable. - A similar situation is obtained with the square of the circle - the task of constructing a square equal in area to a given circle. The task is reduced to the construction of the number

that is not a root of any polynomial from Q [x] at all and has no degree over Q.

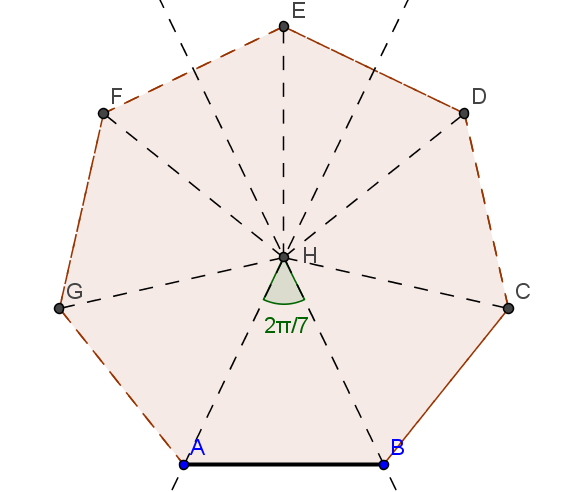

that is not a root of any polynomial from Q [x] at all and has no degree over Q. - The construction of a regular heptagon is impossible. It comes down to the construction of the numbers cos (2𝜋 / 7) and \ or sin (2𝜋 / 7) from the field Q. The seventh root of the unit z = e 2𝜋 / 7 is the root x 7 -1 = (x-1) (x 6 + x 5 + ... + 1) and has degree 6 over Q, since the second factor is irreducible. On the other hand, z has degree 2 over L = Q (cos (2𝜋 / 7), sin (2𝜋 / 7)), since z = cos (2𝜋 / 7) + i sin (2𝜋 / 7) ∈L (i) and [L (i): L] = 2. Therefore, L has degree 6/2 = 3 ≠ 2 n over Q and is not attainable.

- The construction of a regular 17-gon, on the contrary, is possible, because z = e 2𝜋 / 17 is the root x 17 -1 = (x-1) (x 16 + x 15 + ... + 1) and has degree 16 = 2 4 on Q. In general, it works for any p-gon, where p is a prime number such that p-1 = 2 n . Such numbers are called Fermat primes. Pierre Fermat himself argued that all numbers of the form 2 2 ^ n +1 are simple, true to their habit, without proof. However, this was soon refuted. The correct 65537 gon corresponding to the maximum known simple number Fermat was built by Johannes Hermes, a man of outstanding patience, with the help of ordinary compasses and rulers in 1894.

I hope that I was not too tired of my dear readers with an abundance of calculations and was able on such a simple example to demonstrate the beauty and close interconnectedness of different sections of mathematics. I will be glad to see comments and comments.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/225293/

All Articles