How-to: Stock Market Futures Trading

Not so long ago a topic on futures contracts in the stock market was published on our blog. He aroused a certain public interest, but many habra users were not satisfied with the simplified theory and began to ask deeper practical questions. We cannot leave them unanswered, so today we are publishing material with an in-depth description of futures trading.

How are futures exchanges organized

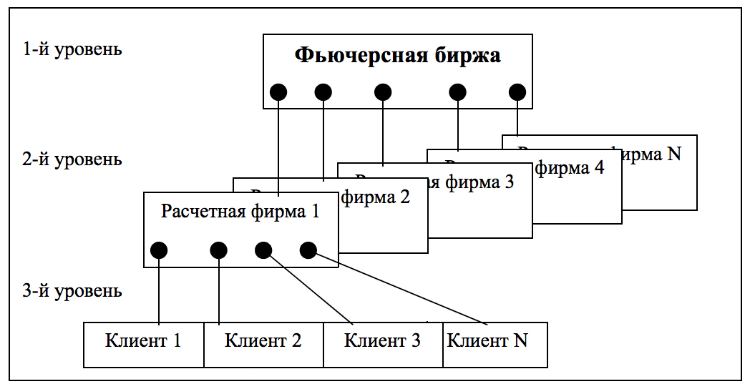

First, again, a little theory. Like many other exchanges, futures exchanges are organized on a three-level basis.

')

At the first level of the hierarchy is the exchange itself, which includes a clearing house (serves the accounts of bidders), a trading system (a means to reduce orders and register trades), and a clearing house. Because of the need to keep records of the collateral (GO - more details about it below), clearing is often conducted in real time, which imposes certain requirements on the technical infrastructure of the trading system.

The Exchange maintains the accounts of all its members, which are called settlement firms (RF).

Clearing houses are the second level of hierarchy. They are professional market participants who own licenses for work - brokers. The clearing company keeps accounts of its clients (individuals and legal entities), which are non-honest bidders - they represent the third level of the hierarchy.

The arrows in the figure symbolize the participants' trading accounts. Brokers (clearing houses) maintain accounts for their clients, and brokers accounts for the stock exchange. This way of organizing trading in the derivatives market transfers some of the clearing functions to clearing firms, reducing the burden on the clearing house of the exchange.

The FORTS section of the Moscow Exchange has a slightly different, though similar, principle. There is also a three-level hierarchy on FORTS: the clearing house — clearing houses — clients. But unlike the general case discussed above, the clearing house keeps trading accounts of all clients of each accounting firm. Accordingly, the GO of clients is calculated online by the exchange, and the broker does not need to do this. Such an organization, when both the clearing and calculation of the GO for transactions are carried out centrally by the exchange is safer for the bidders.

Another interesting issue in the organization of trading in the derivatives market, including futures, is the system for guaranteeing the execution of transactions.

How to guarantee the execution of the transaction

Since there are always two parties at the conclusion of a futures contract - the seller and the buyer, when the price moves in either direction, one of them will always incur a loss, and the second will receive an equal profit. It turns out that the sum of profits and losses of all bidders is zero to within the clearing fees paid by the exchange.

If the loss on positions (negative variation margin) of any losing participant exceeds the amount of its free cash flow, then there is a risk that it will not fulfill its obligations. If he has nowhere to get money to replenish the account and close a losing position, then the broker will be responsible for his obligations.

If a clearing house has many such clients and its own funds are not enough to pay off their liabilities, then reserve funds made up by the exchange itself and, finally, its statutory fund are used.

Such a multilevel system as a whole with a high degree of probability guarantees the participants execution of concluded deals. In addition to funds formed by the exchange, there are other principles of the organization of trade, aimed at reducing risks.

First, it is a rule that forces participants to either bring money in the event of a loss, or to forcibly liquidate a part of their positions. Also, one bidder may not have more than 20% of open positions on the exchange on any of the contracts being traded. Otherwise, for one merchant the risk will become too great, besides there is the possibility of price manipulation.

But despite all the rules, the procedure and method for determining the collateral is the most important element in building a system for guaranteeing forward transactions.

Initial Margin (GO)

Sometimes the value of the collateral is called the "initial margin". Here are some principles that a reasonable choice can satisfy:

- GO value should be as high as possible. The purpose of this is to ensure guaranteed fulfillment of obligations by bidders.

- GO value should be as low as possible. The purpose of the increase is to attract speculators who provide market liquidity.

In the struggle between these two principles, rules for establishing the initial margin are developed. When making a transaction, the exchange blocks the value of GO multiplied by the number of contracts purchased or sold on the seller’s and buyer’s accounts. These funds are not withdrawn from the account, but cannot be used until the position is closed and the GO is released.

What remains after blocking GO is called free money, you can open further positions solely on this money. That is, the opening of new positions reduces the amount of available funds and simultaneously increases GO. And vice versa - the closing of positions releases GO and leads to an increase in available funds.

The initial margin can not be too low - it increases the risk of default on their obligations by bidders. The size of the HO must be sufficient to cover the cash gain with the maximum possible two-day rise or fall in price. Every day the exchange for each instrument sets the limits for daily price change, so that the value of GO cannot be less than a double limit. It is about two days, so that bidders can manage to replenish their account, with the unsuccessful development of events on the first day.

Variation margin

Many questions to the past topic were reduced to an understanding of the concept of variation margin. Once again we will understand what it is.

Variation margin, which is accrued and debited based on the results of daily clearing - this, in fact, is the profit or loss of the bidder.

Unlike an investment account with shares, there is no concept of unrealized profit / loss on an open position on a futures account. The entire loss (or profit) unrealized during the trading day is written off or credited to the account in the form of a negative or positive variation margin. As a result of such write-off / crediting, the cash balance of the account changes and a simultaneous revaluation of the value of the positions occurs.

It allows speculators to easily get rid of their obligations when closing all contracts (otherwise they had to sell or buy a basic asset of futures from someone in the future, which is not at all in their plans) and immediately get a profit or loss. The exchange “does not remember” the next day who, what and at what price bought or sold, it only wonders how many of whom have any obligations.

Let's talk more about the revaluation. In the case of purchase of shares, funds in the amount of the purchase are debited from the account, and securities are credited to the depot account. Further, prices in the market may vary in one direction or another, but the number of securities on the account and the amount of money do not change.

Everything is wrong on the futures market. The difference arises from the futures description itself:

A futures contract is an electronic record of a commitment by a broker to deliver or to accept a certain amount of the underlying asset on a specific date in the future.

Futures by itself is not an asset or liability - it is only a record of a deal. Therefore, when buying or selling futures, funds from the participants in the transaction are not written off, but are blocked as GO. It turns out that at any time during the trading day the equality is true:

Account balance = free balance + GO = fixed value.

The CO changes with each filing and withdrawal of the order and with each transaction. It is forbidden to perform operations that withdraw funds in the negative zone. Inside the trading day, available funds should be positive.

After the trades, clearing takes place - that is, recalculation of all positions and accrual / write-off of the variation margin. Margin is added or debited from available funds. If there are not enough of them, then a debit balance is formed in the merchant’s account, which he is obliged to cover with additional money or by closing part of his positions until the end of the next trading day.

Consider a couple of examples of calculating the variation margin:

Example 1

In the morning, the merchant was opened 6 "long" contracts. The closing price (clearing price) was 19,900 yesterday.

The trader did not perform any operations during the day, today's closing price was 20,000. Variation margin, as can be seen, is positive and amounts to

6 * (20,000 - 19,900) = 600 rubles

Example 2

In the morning, the merchant had no contracts. During the trading day, he bought 6 contracts at a weighted average price of 19,850. The closing price of the trading day was 20,000. The variation margin is again positive and is:

6 * (20,000 - 19,850) = 900 rubles

Example 3

In the morning, the merchant had 6 long contracts. The closing price (clearing price) yesterday was 19,900.

During the day, he sold all contracts at 19,850. The closing price of the trading day was 20,000. Variation margin is negative and is

6 * (19.850 - 19.900) = -300 rubles.

Thus, the variation margin for one long contract is calculated by the formula:

Vm = (c1 - c0) * Step cost / minimum step,

Where c1 is the contract sale price (if it was sold before closing) or the session closing price (estimated price), and c0 is the contract purchase price (if purchased today) or the closing price of the previous trading session (if it was purchased earlier).

For a short contract, the opposite is true:

Vm = - (c1 - c0) * Step cost / minimum step,

Where c1 is the buyout price of the contract (if bought off before closing), or the session closing price (estimated price), and c0 is the selling price of the contract (if it was sold today) or the closing price of the previous trading session (if it was sold earlier).

For contracts whose exchange rate is pegged to the dollar, the calculations are more complicated.

Example 4. RTS Index

On a certain day, the trader sold 10 contracts at 164,700 and closed his short position at 163,900. The exchange rate of the US dollar on that day was, say, 35 rubles.

Variation margin is positive and is:

Vm = 10 * (164,700 - 163,900) * 0.1 / 5 * 35.00 = 4 572 rubles

To determine the variation margin, the same formulas were used as in the examples above, but you need to understand that the cost of a step depends on the current dollar rate.

Yield for delivery

Another common question in the comments to the past topic was about how the delivery takes place, in the case of delivery contracts.

With a long position on futures deliverable contracts, the buyer must have enough money in the account so that he can pay for the underlying asset upon delivery.

On the contrary, in the event of a delivery with a short position, the buyer should reserve the basic asset in an amount sufficient for sale at the strike price.

To enter the delivery, the merchant must have the means to carry it out and he must give notice of his desire to make the delivery. Failure to comply with any of these conditions incurs a penalty in the form of GO loss.

That's all for today. Thank you for your attention, we will be happy to answer questions in the comments (something covered in the FAQ on our website).

Links and related articles:

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/223311/

All Articles