Bleeding Heart Status: Upgrade to Broken

For information: In many references to this article, the authors mistakenly call me an employee of Opera Software. In fact, I left Opera more than a year ago and today I work in a new company - Vivaldi Technologies AS

May 12 Update

After a more thorough investigation of the problem in conjunction with F5, it turned out that the test used to detect the F5 BigIP servers showed higher numbers than it should be, therefore the number of such servers turned out to be overestimated. This means that the corresponding BigIP server information and conclusions are incorrect, so I’ll delete the chapter on BigIP servers. I apologize to the F5 and their customers for this error.

')

Prehistory

As I mentioned in my previous article , a few weeks ago, a vulnerability was discovered in the OpenSSL library ( CVE-2014-0160 ), which received the loud name " Heartbleed ". This vulnerability allowed attackers to extract such important information as, for example, user passwords or private site encryption keys, penetrating vulnerable "protected" web servers (an explanatory comic ).

As a result, all affected websites had to patch their servers, as well as perform other actions in order to protect their users. It is worth noting that the level of danger has increased significantly after information about the vulnerability spread through the network (several serious incidents were recorded and at least one person who tried to use Heartbleed for personal gain was under arrest).

Slow down patch usage

For several weeks from the day the vulnerability was discovered, I monitored the activity of the patch application using my own TLS Prober tester. Currently, the tester scans approximately 500,000 individual servers using changes to host names in different domains (a total of 23 million) with a sample of about a million websites from the Alexa Top.

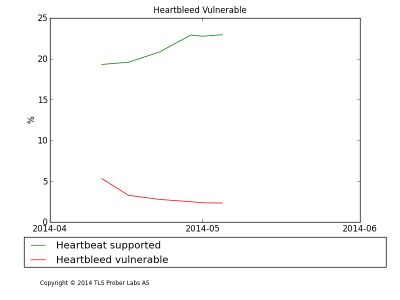

According to the six scans that I carried out from April 11, the number of vulnerable servers dropped sharply from 5.36% of all servers checked to 2.33% this week. About 20% of the scanned servers support the Heartbeat TLS Extension, this suggests that up to 75% of the vulnerable servers were patched during the first four days after the vulnerability was discovered, i.e. before my first scan.

However, if in the first two weeks of scanning the number of vulnerable servers was reduced by half - to 2.77%, in the next couple of weeks this figure decreased only to 2.33%, which indicates an almost complete halt in the process of “curing” vulnerable servers.

In general, a scan reveals that the servers of the most popular websites were patched. About 73% of the websites scanned use certificates from the Certificate Authority that are recognized by browsers, and only 30% of vulnerable websites use such certificates. All this slightly reduces the importance of the problem as a whole, but even if some servers look insignificant on the scale of the entire Internet, it is no easier for real users of these servers.

There is an equally serious problem: many certificates used by vulnerable servers continue to be used on repaired servers. In fact, if we assume that all the servers that supported Heartbeat were scanned before this for the first scan, 2/3 of the certificates were not updated after repairing the servers using a patch (because they turned out to be the same as before ). Considering that each server patched after April 7 allegedly possessed a compromised certificate private key (after all, attackers could use Heartbleed on these servers), we can talk about a serious problem that still threatens users of such websites.

In addition, digging in numbers revealed two more problems.

Upgrade to Broken Heart

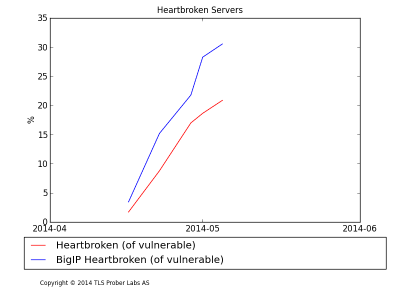

The second problem is also related to the number of vulnerable BigIP servers, but it looks much worse: during my last scan, 20% of currently vulnerable servers (sampled by IP) were detected,

One would assume that the identified numbers are wrong, because the analysis assumes the immutability of the IP addresses of the servers, which is not always the case. However, using the same methodology for verifying server certificates shows the same trend.

It is hard to say exactly where this problem came from, but one of the possibilities is that the heightened attention to the topic from the media has led server administrators to doubt that their servers are safe enough. To this could be added pressure from the authorities with the requirement “not to be idle”, as a result, the software was updated completely protected from the misfortune of the servers to the new version, which at that time was not yet fixed by the developers themselves.

To fix this problem, owners of vulnerable servers will have to go through the entire patch application procedure again, which will lead to monetary costs, which could in fact be avoided. Roughly, applying a patch, replacing a certificate, and carrying out appropriate testing will require three system administrators to work for four hours. With the cost of each admin hour at $ 40, the approximate total amount of extra costs for correcting 2500 “diseased” servers (in my example) can be about $ 1.2 million. And considering that my testing covers only about 10% of all servers in the network, the total contingency costs will be $ 12 million.

Heartbleed is a very serious problem and fixing this vulnerability needs to be made to all affected servers, but I begin to think that the activity of the thematic press, suffering from inaccuracies and giving early advice (such as “change your password immediately!” without waiting for the server software update or “certificate revocation due to Heartbleed to significantly slow down the speed of the network”), is, to some extent, counterproductive.

The aforementioned data on servers that have been “updated” and thus become vulnerable to a problem that had not been addressed before, may be the result of a distorted press coverage of the problem.

My recommendations remain the same: first we install the patching patch, then we update the certificates, and only then we change the passwords (in that order). Thematic journalists should concentrate on this, and all panic should be eliminated completely. Observe actual accuracy when discussing a problem, offer readers ways to check (can they become a victim of a vulnerability), for example, tell us about existing software tools, such as SSL Labs Server Tester , and do not forget to tell you how to get rid of the problem.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/222337/

All Articles