Wolf hunters from Wall Street. Part 2

Adaptation from the book by Michael Lewis "Quick Boys"

[ This is the second part of a series of adaptations of the recently published book by Michael Lewis. The first part can be read here - approx. transl.]

It has always seemed to people that since Brad Katsuyama is Asian, he must be a computer genius. In reality, he could not (or did not want) to even set up his digital player. What he really could do was distinguish which IT professional really knew his business and who didn't. So he was not particularly surprised when in the RBC [ Royal Bank of Canada, Royal Bank of Canada - approx. transl.] eventually stopped trying to find someone who could restore order in their electronic bidding, and asked him, Katsuyama, to take on this task. He, however, seriously puzzled his friends and colleagues by agreeing to undertake this, despite the fact that: a) he already had a calm and “dust-free” job of managing live traders, for which he received $ 1.5 million. year and b) RBC had nothing to add to the electronic bidding process. The market was confused; large investors needed only a few trading algorithms that brokers distributed, and Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse have long occupied this niche.

So, Katsuyama headed a business called electronic trading - despite the fact that he could sell only useless software from Carlin Financial. What he had at that moment was in abundance was questions that were not answered. Why, for example, in the interval from public stock exchanges to dark pools [of liquidity] - private exchanges that are created by banks and brokers who do not report their trading activity in real time - there are at least 60 organizations, mostly located in New Jersey, where can I buy any stock listed on the stock exchange? Why do they pay for one action or another at one exchange, for example, for selling shares, while at the other, they charge you for the same action? Why is the state of the market on the screens of computers from Wall Street turns out to be fiction?

')

Katsuyama hired Rob Park (Rob Park), a gifted IT specialist, to explain to him what is actually happening inside all these “black boxes” from Wall Street, and together they began to assemble a team to investigate what was happening in the US stock market. Once the team was formed, Katsuyama convinced his bosses at the RBC to go for what had resulted in a series of experiments. Over the next few months, he and his guys planned to trade stocks not for profit, but to test their theories. The RBC agreed to give the team the opportunity to spend up to $ 10,000 a day to find out why the market conditions for each selected stock changed radically each time when RBC tried to carry out a particular trading operation with it. Katsuyama asked Park to think about which theories can explain this.

They started with public markets, with 13 stock exchanges located in four different locations and led by the New York Stock Exchange, the Nasdaq, BATS and Direct Edge. The first theory of the Park was that exchanges do not group together all orders at the same price, but arrange them in a certain sequence. You and I can enter an order to buy 1,000 shares of Intel at $ 30 a share, but you can somehow get the right to cancel your order if mine was executed. “We began to grow stronger in the opinion that people canceled warrants,” says Park. "What were these phantom orders."

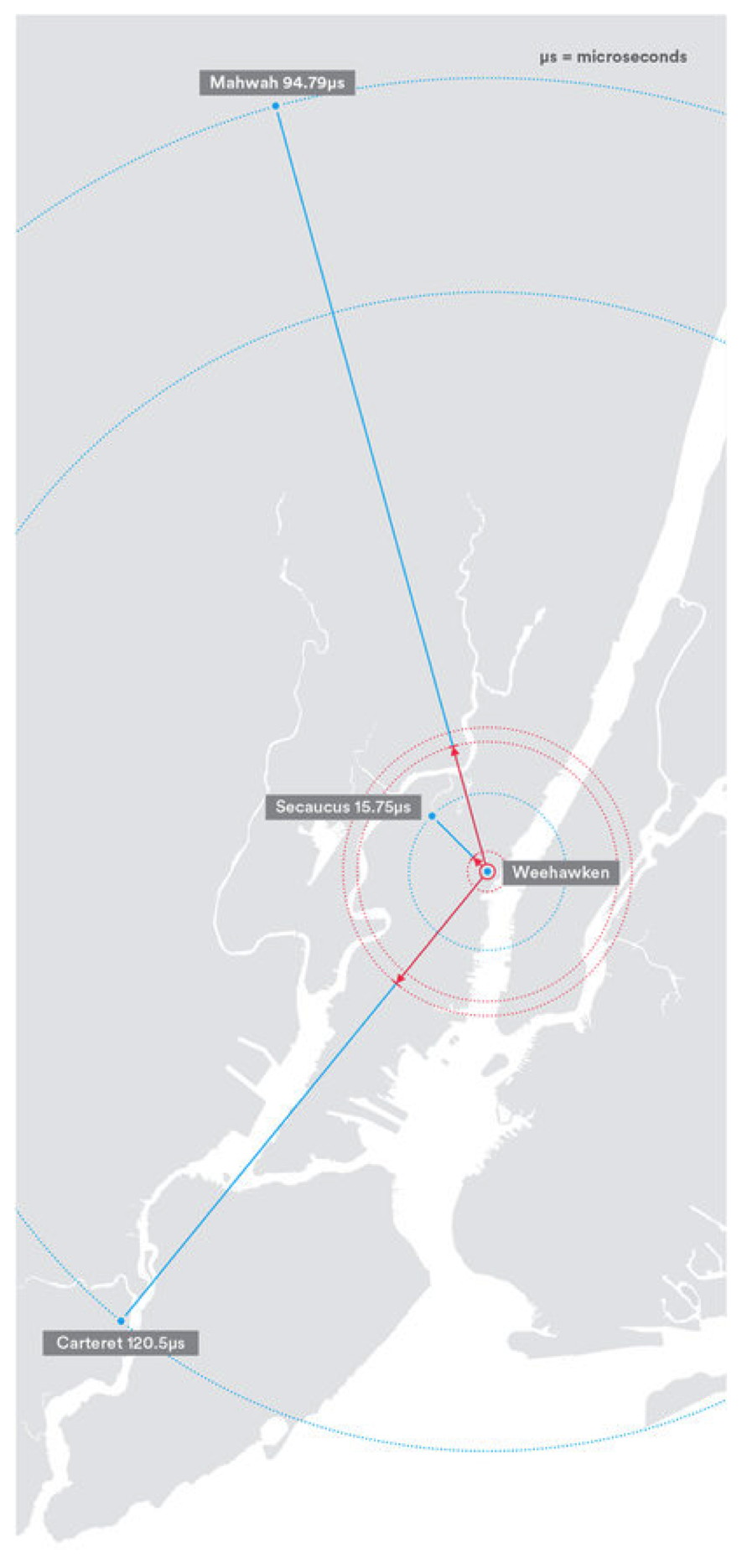

This box, stored in a building in Secaucus, New Jersey, contains a 38-mile fiber optic cable, which creates small delays when processing orders, thereby equalizing the chances of different traders.

Katsuyama tried to send orders to selected stock exchanges, almost certain that this could confirm that some or even all exchanges allow phantom orders to appear. But no: to his surprise, he found out that according to the order sent to a specific stock exchange, he could easily buy the shares put up for sale. What he saw on the computer screen was indeed the real state of the market. "I thought ... with her, with this theory," says Katsuyama. "And I also thought that we have no other theory."

There was no point in this: Why are the market data on the computer screen real if you send an order to a specific stock exchange, but no longer correspond to reality if you send an order to all the exchanges at once? The team began to send orders to groups of exchanges in various combinations. The first were the New York Stock Exchange and the Nasdaq. Then came the New York Stock, Nasdaq and BATS. Then came the New York Stock, Nasdaq BX, Nasdaq and BATS. And so on. And the further it went, the more mysterious it became. The more exchanges were on the list, the less the percentage of order execution became, the more sites on which they wanted to buy stocks became, the fewer shares they eventually managed to buy. “There was only one exception,” says Katsuyama. “No matter how many exchanges we sent warrants, we could always buy all the shares offered on BATS”. Park did not have this explanation: “I just decided that BATS must be a great exchange!”.

One morning , while taking a shower, another theory occurred to Rob Park. He tried to imagine what he had seen before that, showing how long it took to send the order from the computer of Brad Katsuyama, located at the World Financial Center, to each of the exchanges.

The amount of time required for this operation was fantastically tiny: in theory, the fastest order from the Katsuyama computer in Manhattan reached the BATS exchange in Vihokene, New Jersey — it took two milliseconds. The longest warrant went to the Nasdaq Stock Exchange in Carteret, New Jersey — it took four milliseconds. In practice, these numbers could vary significantly depending on the traffic on the network, as well as equipment failures between the two points. Even to quickly blink you need 100 milliseconds - and the more difficult it was to believe that in less time than we spend blinking something could happen that has real consequences on the market. Allen Zhang, whom Katsuyama and Park considered the most talented programmer on the team, wrote code embedding “delays” in the process of sending orders to “nearby” exchanges, so that they came there at the same time as on exchanges "Distant". “It was illogical,” says Park, “because everyone told us: the faster, the better. We should have accelerated, and we, on the contrary, tried to slow down. ” One morning they sat down to test the program. When a purchase order was sent from the computer, which was not executed as a result, the screens were lit in red. When the order was partially executed - brown, and when fully executed - green.

And this time the screens turned green.

Speed trading

For the microseconds that a high-frequency trader needs for his order to reach various stock exchanges located in the cities of the state of New Jersey (blue lines), an order of an ordinary trader usually only goes the distance marked in red. The time gap - which is now under the supervision of the Attorney General of New York - can in some cases bring financial benefits.

“It was 2009,” says Katsuyama. “Before that, I observed a similar picture for two years and was definitely not the first to find out what is really happening. So what happened to the others? ”The answer, apparently, was contained in the question itself: everyone who figured out the problem tried to make money on it.

Now he and RBC received a tool that could be sold to investors: a program written by Zhen, which embedded delays in the process of sending orders. This tool allowed traders, such as Katsuyama, to do their job - to take the risk on behalf of large investors and trade large volumes of shares. Now such traders could re-trust the numbers on their computer screens. The program needed a name. The team puzzled, until one day some trader jumped up with a shout: “Dude, you have to call this thing Thor [Thor]! The hammer! ”[ In the original article, the hammer and the Torah itself are called the same, but the“ canonical ”name of the hammer of the Torah is Mjöllnir - approx. trans.]. Someone was asked to come up with a phrase that could be shortened to the acronym Thor - the words were picked up, but no one remembered them. The program and began to call - Thor. “I realized that we came up with something really worthwhile when the word Thor was used as a verb,” says Katsuyama. “When I heard someone shout,“ Thor it! ”

Another proof that they have found the right approach to solving the problem was the meeting of Katsuyama with some of the largest investment managers in the world. Katsuyama and Park made their first visit to Mike Gitlin (Mike Gitlin), who led the global trade in million-dollar assets for the investment manager T. Rowe Price. The story they told did not seem to Gitlin a complete surprise. “You could see how something had changed quite recently,” said Gitlin. “You could see that when you try to trade stocks, the market understands what you are going to do and starts moving against you.” But Katsuyama described a much more detailed picture of the stock market — a picture that Gitlin hardly imagined — and everything seemed suspicious in this market. The Wall Street brokerage company, which decided whether to send buy or sell orders from T. Rowe Price to the market, had a great influence on how and where these orders were executed. At the same time, some exchanges paid broker companies for their orders, while others, on the contrary, themselves charged for this.

Did this not affect where the broker decided to place an order - even if the decision went against the interests of investors that the broker had to represent? No one knew for sure. Another suspicious activity was the "payment for the flow of orders." By 2010, every brokerage company in the United States and all online brokers effectively traded their clients' orders at auctions. The online broker TD Ameritrade, for example, was paid hundreds of millions of dollars annually for sending orders to a hedge fund called Citadel, who worked with them on behalf of TD Ameritrade. Why was Citadel willing to pay so much for the opportunity to monitor the flow of orders? No one knew for sure what the benefits of Citadel were.

Katsuyama and his team calculated how much cheaper they began to buy stocks when they eliminated the likelihood that some unknown traders could conduct a forward transaction. For example, they bought 10 million shares of Citigroup, and then, when the shares were trading at $ 4 per share, they got $ 29,000 from them - or less than 0.1% of the total price. “It was practically an“ imperceptible ”gathering,” says Park. This amount looks insignificant until you know that the average trading volume in the United States in one day is $ 225 billion. The same fee for all of this amount is almost $ 160 million per day. “It was so tricky to do this, because you couldn't know about anything,” says Katsuyama. “This happened on such a tiny scale [ with a huge frequency of operations per unit of time - approx. perev.], that even if you tried to bring the whole process to clean water, you could not do it. People are deceived because they cannot imagine a microsecond. ”

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/220363/

All Articles