Soviet operation to save the dead space station

Source: Spacefacts.de

This story took place in 1985, but later was gradually forgotten. The years went by - many details were distorted, something was invented. Even those who were the first to speak about these events made obvious mistakes. Operation Soyuz-13 to rescue the Salyut-7 orbital station was an impressive attempt to carry out repairs in open space. The writer Nikolai Belakovsky has gathered all the facts together and is ready for the first time in all time to provide us with a full story about those events.

It gets dark and Vladimir Dzhanibekov gets cold. He has a flashlight, but no gloves: it is more difficult to work with them, but you need to cope quickly. Hands freeze, but it does not matter. The water reserves of his team are limited and if they do not repair the station on time, its systems will not have time to warm their drinking tanks, and they will have to leave it and go home. This can not be allowed: the station is too important. The sun is setting. It’s inconvenient to work with a lantern alone, so Dzhanibekov returns to the ship that brought them here to warm up and wait until they fly past the night side of the Earth. [one]

')

He is trying to save the Salyut-7, the newest of a series of problem, but increasingly successful Soviet space stations. His predecessor, Salyut-6, finally returned the title of the longest-running human-controlled space programs to soviet stations, beating the 84-day record set by American Skylab in 1974 by 10 days. Further flights extended it to 185 days. And after the launch of the Salyut-7 into orbit in April 1982, the first flight to it updated the record to 211 days. The station began its existence without any serious problems. [four]

The situation changed quickly. On February 11, 1985, at the time when Salyut 7 was in orbit, controlled by autopilot while waiting for its next team, the Mission Control Center detected a problem. The telemetry system reported a drop in current in the electrical equipment, which led to the overload protection to be triggered and the electrical circuits of the main radio transmitter disconnected. Redundant radio transmitters switched on automatically, eliminating the threat of station loss. Tired at the end of their 24-hour shift, the MCC Operators recommended contacting specialists from the design bureau responsible for building electrical and radio systems. Specialists had to analyze the situation, provide a report and recommendations, but at that time the station was in order, and the next shift was ready to take up duty. [9]

Without waiting for the experts to arrive, and perhaps from the very beginning without bothering to call them, the operators of the next shift decided to restart the main radio transmitter. They assumed that the overload protection worked by chance, and even if it didn’t, it was still active and if there was a problem, it would have worked again. Operators, acting contrary to the established traditions and procedures of their department, gave the command to re-activate the main radio transmitter. At the same time, a whole series of short-circuits flashed through the station, which not only the transmitters but also the receivers were damaged. February 11, 1985, at 13:20:51 MSK "Salyut-7" was silent and stopped responding to the commands of the Center. [8] [9]

What to do?

This situation put the flight operators in an awkward position. One of the available options was to simply drop the Salyut-7 and wait until his successor, Mir, became available for programs of human activity in space. The launch of the World was to take place within a year, but waiting for it meant not only delaying the space program for a year. This would also lead to the fact that the entire amount of scientific work and engineering tests planned for Salyut-7 would remain unfulfilled. Moreover, the admission of defeat would be a shame for the Soviet space program, especially painful on the background of the number of previous failures of the Salute series, as well as the obvious success of the Americans with their Space Shuttle program.

There was only one option left: send a repair team to the station to fix it from the inside, manually. However, this idea could easily have ended in another failure. The standard docking procedures with the space station were fully automated and relied very heavily on the exact orbital and spatial coordinates information that the station itself was sending. In those rare cases when the automation did not work and a call was made to the manual docking, all the main difficulties arose hundreds of meters from the station. The question arose: "How to dock with a sleeping station?" [9]

The lack of communication created another problem: it was impossible to know the condition of the onboard systems. The station was designed for autonomous flights, and in the current situation it was the maximum number of failures it could cope with, after which human intervention was required. At the time of the arrival of the repair team, it could be in good condition, requiring repairs only for the replacement of damaged transmitters. Perhaps there was a fire on it or a depressurization occurred due to a collision with space debris. Anything could have happened, but it was probably impossible to find out. [3]

Officially, the general public is not aware of whether there has been a discussion and consideration of options for resolving the current situation at the level of senior management. "It is known" however, that the Soviet leadership decided to conduct a repair operation. This meant that it was necessary to develop all the docking procedures from a clean slate, hoping, in addition, and also that during the absence of communication there was no malfunction on board the station, because otherwise the repair team could not cope with the task. It was a bold decision.

"Docking with an uncorporated object"

The primary task of the repair team was to determine how it could get to the station. In more favorable conditions, the Soyuz (a 3-seater ship that was used to deliver astronauts to the station and back) would hardly get into orbit and receive information about the station from the MCC, long before it came into view of the crew . The messages would contain information about the orbit of the space station, which would enable the approaching ship to calculate the rendered orbit. Once the distance between the ship and the station reached 20-25 km, they would establish a direct communication and the automatic system would bring them together, completing the docking. [3]

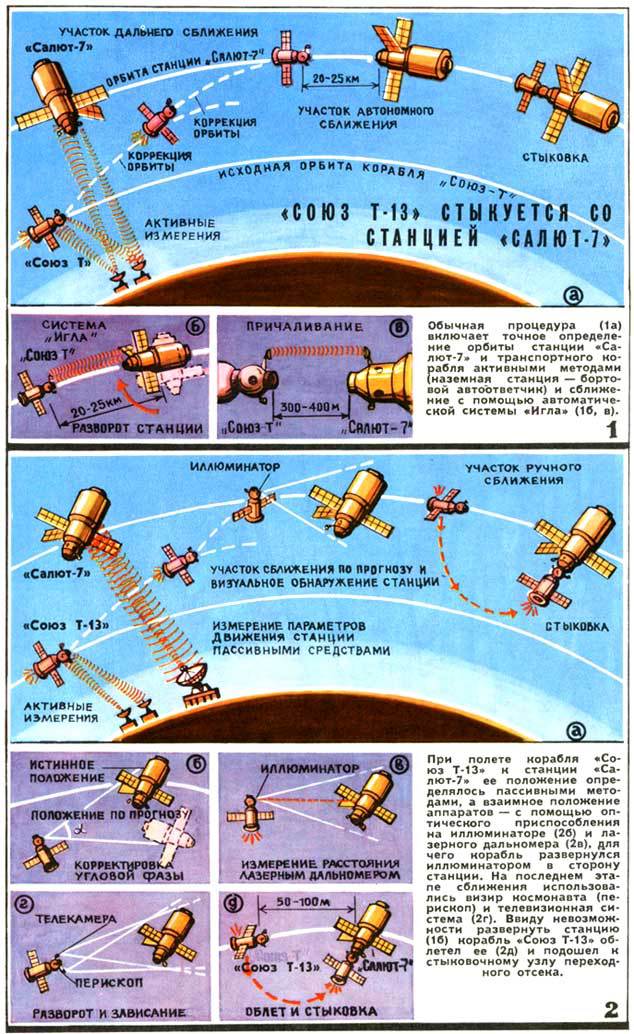

The first part depicts the normal procedure for approaching and docking the Soyuz, the second shows its modified version, which was used by the Soyuz T-13. Please note that in Figures 2b and 2c the ship flies sideways in order to see the station through the porthole.

The pilots of the "Union" were trained in manual docking, but malfunctions in the operation of the automatic system occurred rarely. The most serious incident occurred in June 1982, when a computer crash interrupted the Soyuz T-6 automatic convergence process 900 meters from the station. Vladimir Dzhanibekov immediately took over the management and successfully docked his "Soyuz" to the "Salyut-7" as much as 14 minutes before the scheduled time. [4] It is quite natural that Janibekov was the main candidate for the role of pilot in any possible mission to rescue Salyut-7.

It was necessary to develop a series of completely new docking techniques, which was done in the framework of the project called “Docking with an uncooperative object” [5]. The station’s orbit was supposed to be measured using a ground-based radar with information transfer to the Soyuz convergence course. The goal was to bring the ship to a distance of 5 km from the station, from which the manual docking was considered theoretically possible. [3] The engineers responsible for developing the new procedures came to the conclusion that, after making the appropriate modifications to the Soyuz, were 70-80%. [2], [3] The Soviet government took a risk, considering the station too valuable to simply allow it to lose orbit in the absence of control.

"Union" began to modify. The automatic docking system should have been removed by setting the laser rangefinder in the cockpit to help the team determine the distance and speed of the approach. The crew also had to provide night vision devices in case they had to dock on the night side. The seat of the 3rd crew member was removed, and additional supplies, such as food, and, later on, vital, water was brought aboard. The weight saved by removing the automatic system and 3rd place was used to fill the fuel tanks to the highest possible level. [1], [3], [11]

Who will fly for surgery?

When it came to choosing the team for the flight, it was necessary to take into account two important points. First of all, the pilot should have experience in performing manual docking in orbit, and not only on simulators. Secondly, the onboard engineer should have known the Salyut-7 system very well. Only three astronauts previously performed manual docking in orbit: Leonid Kizim, Yuri Malyshev and Vladimir Dzhanibekov. Kizim only recently returned from a long mission on the Salute-7 and was still undergoing rehabilitation after this flight, which excluded him from the list of possible candidates. Malyshev had little flight experience. He also did not undergo training in spacewalk, which would have been necessary later in the course of the operation in order to install additional solar panels on the station, in case its restoration would be successful. [one]

There remained only Dzhanibekov, who spent 4 flights in space from one to two weeks, while being trained for long-term operations and spacewalks. However, doctors forbade him to participate in long flights. Dzhanibekov, who was the first in the list of key candidates for the role of commander of the ship, was quickly transferred into the hands of doctors, who after several weeks of observation and inspections, allowed him before the flight, the duration of which should not exceed 100 days. [one]

The list for the role of flight engineer was even shorter and consisted of only one person. Victor Savinykh had previously performed one flight on the Salyut-6 for a duration of 74 days. In the course of that operation, he provided work for Janibekov and the first cosmonaut of Mongolia, who visited the station at Soyuz-39. Among other things, he was already preparing for the next long-term operation at Salute-7, the launch of which was scheduled for May 15, 1985. [one]

By mid-March, the crew was approved. Vladimir Dzhanibekov and Victor Savinykh were chosen to attempt to carry out the most daring and most difficult at that time repair activity in open space. [one]

Go!

On June 6, 1985, almost 4 months after losing contact with the station, the Soyuz T-13 launched with commander Vladimir Dzhanibekov and flight engineer Viktor Savinykh on board. [1], [6] After two days of flight, the station appeared in sight.

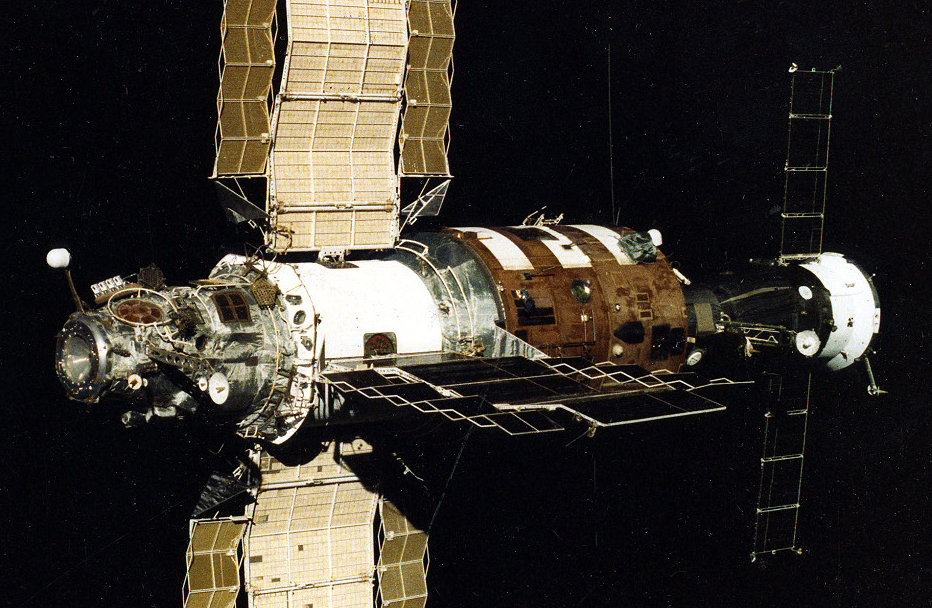

During the approach to the station from the ship, live video was filmed, which was broadcast to the Control Center. Here is one of the images taken then:

"Salute", how he saw the crew of the approaching "Union T-13".

Notice that the solar panels are tilted at different angles.

Source: Wikimedia

The PMU operators noticed something was wrong: the station’s solar panels were not parallel. This indicated a serious malfunction in the system, which orients the solar panels at the Sun and caused concern about the state of the entire electrical system of the station. [one]

The crew continued to approach.

V. Dzhanibekov : “The distance is 200 meters, we turn on the engines for overclocking. The approach is at a low speed, in the range of 1.5 m / s. The rotational speed of the station is within the normal range; it has practically stabilized. Here we hang over it, unfold ... Well, now we will be a little tormented, because in the sun we are not doing well ... Here the image has improved. Crosses are combined. The mismatch of the ship and the station in the admission ... Normally, there is control, I quench the speed ... wait for the touch ... "

Slowly and quietly, the crew of the Soyuz flew towards the front docking station of the station.

V. Savinykh : “There is a touch. There is mekhzakhvat.

The successful docking with the station was a major victory, and for the first time in history, it showed that it is possible to get close and dock with almost any space object. However, it was too early to celebrate: the team did not receive from the station any physical or electronic confirmation of the docking. One of the main concerns that, during a lack of communication at the station, serious problems quickly became a reality.

The lack of information on the ship’s screens about the pressure inside the station raised fears that it was depressurized, but the crew carefully continued their work. The first thing was to try to equalize the pressure on the ship and the station, as far as possible. [1] [3]

As in the old, abandoned house

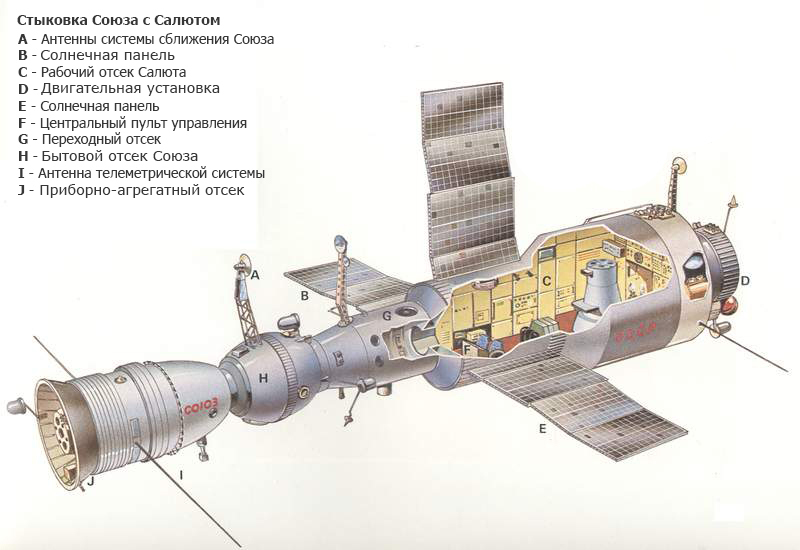

All Soviet and Russian space stations, starting with Salyut-6, had at least 2 docking nodes: the front one, which connected to the transition compartment and the rear one, which connected to the main compartment of the station. The rear hub also had a message with the station's fuel tanks, which made it possible to replenish them with the help of the Progress cargo ship, which carried out cargo delivery flights to the station. The team docked to the front node and began to equalize the pressure. The Salyut-7 was designed on the basis of the Salyut-6 and had a structure similar to it, the scheme of which is given below:

Source: spacecollection.info

The diagram shows the docking of the Soyuz (left) with the Salyut-4. The ship is connected to the transition compartment (G), the hatches of which lead to section H on the Soyuz and section C on the station. Starting from the 6th generation of the Salyut, section D was modernized: it contained not only the mechanical section, but also the docking station. Soyuz ships are able to dock with both nodes, while Progress ships can dock only with the back.

To get to the main branch of the station, which is called the "working compartment", the crew had to overcome, in total, 3 hatches. First, they needed to open the hatch of the ship and, through a small hole in the hatch of the station, to equalize the pressure between the ship and the transitional compartment of the station. Having done this and checked the transitional compartment, they could start working with the hatch separating the transitional and working compartments of the station.

Earth: "Open the hatch of the ship."

V. Savinykh: “The hatch was torn off”.

Earth: “Was it hard? What is the temperature of the [station] hatch? ”

V. Dzhanibekov: “The hatch is sweaty [from condensate]. We see nothing else here. ”

Earth: “Accepted. Carefully loosen the cork for 1-2 turns and quickly go to the household compartment. Prepare everything for closing the hatch of the ship. Volodya (Janibekov), you open it for one turn and listen, hiss or doesn’t hiss. ”

V. Dzhanibekov: “I’ve done it. A little hiss. But not so violently. ”

Earth: "Well, just a little bit more."

V. Dzhanibekov: “Well, I turned it down. Hissed. Alignment division.

Earth: "Close the hatch [of the ship]."

V. Savinykh: "The hatch is closed."

Earth: "Let's take another three minutes to see, and then we will move on."

V. Dzhanibekov: “The pressure without changes ... begins to level off. It's too slow. ”

Earth: “What to do! We still fly and fly. Therefore, there is no hurry. ”

V. Dzhanibekov: “The pressure is 700 mm. The difference was 20-25 mm. Now we open the hatch [of the ship]. Opened.

Earth: "Move the cork."

V. Dzhanibekov: "Now."

Earth: "The cork is hissing?" Move the cork. Maybe she will still be poisoning, and leveling thereby. "

V. Dzhanibekov: “Hurry up, yes?”

Earth: "Of course."

V. Dzhanibekov: “We will resolve this issue quickly. This familiar native smell ... So, I open a little hole. Here, now the case has gone more fun. "

Earth: "Hissing?"

V. Dzhanibekov: “Yes. Pressure 714 mm. "

Earth: "Is a spill going?"

V. Dzhanibekov: "Going".

Land: "If you are ready to open the station hatch, you can proceed."

V. Dzhanibekov: “Ready. I open the hatch. Op-a, opened.

Earth: "What do you see?"

V. Dzhanibekov: “No. I mean - the lock opened. I'm trying to open the hatch. We go. "

Earth: “First Sensation? What is the temperature? ”

V. Dzhanibekov: “Kolotun, brothers!”

At this point, the astronauts began to realize the seriousness of the situation. The electrical system of the station lost power, causing the temperature control system to shut down. In addition to the freezing of vital stocks, such as water, it also meant that all the station's systems were affected by temperatures, in which they were not initially adapted to work. The crew was not even sure that it was safe to board the station.

Earth: "Is it too cold?"

V. Dzhanibekov: "Yes."

Earth: "You then cover the household compartment."

V. Dzhanibekov: "No smell, but cold."

Earth: "You now remove the stubs from the portholes"

V. Dzhanibekov: “We open the portholes at once.”

Earth: "On the hatch that you just opened, you need to wrap the cork."

V. Dzhanibekov: “We will do it immediately.”

Earth: "Volodya, by sensation, is it still a minus or a plus?"

V. Dzhanibekov: “Plus, so small, plus five can be there.”

Earth: "Try to turn on the light."

V. Savinykh: “Now let's try the light. Issued a command. No reaction, at least one LED, something would catch fire ... "

Earth: “If it's cold, get dressed ... look around and slowly start working. And everyone needs a snack. With the transition, you! "

V. Dzhanibekov: "Well, thank you."

Soon after, they disappeared from the ground station and lost contact with the Control Center. Today, high-orbit transponder satellites provide a permanent message to the ISS, but at that time communication loss was normal. Later that day, the crew reestablished communication with the Control Center, preparing for an analysis of the working compartment atmosphere, which was planned to be pumped through indicator tubes. They would indicate the presence of ammonia, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and other components whose presence in the atmosphere could indicate that a fire or a fire has occurred on board.

Earth: "How's the temperature?"

V. Savinykh: “Three or four degrees heat. Cool. "

Earth: "How is pressure in the compartment?"

V. Savinykh: “The pressure is 693 mm. Getting to the gas analysis. "

Earth: “Request: when carrying out the analysis, hold the indicator tubes in your hands to increase their temperature. This will increase the accuracy of measurements ... Are you working with a flashlight? "

V. Savinykh: “No, we opened all the windows, it is light here. And in the night we work with a flashlight. ”

Earth: “At the next turn we are planning to open the hatch. And, probably, for today we will finish it. You are already pretty tired. Tomorrow in the morning we will continue. ”

V. Savinykh: "I see."

The indicator tubes showed that the atmosphere at the station was normal, so the team measured the pressure between the compartments, just as they did through the outer hatch of the station, separating the ship and the transitional compartment. Just in case, the Control Center recommended them to wear gas masks and open the hatch.

In winter jackets and lanterns in their hands, they swam into the darkness and coldness of the working compartment, whose walls were covered with an icy touch. Savinykh tried to turn on the light, but as he expected, to no avail. They removed the gas masks, as they further impaired visibility in the dark. There was no smell of fire. Savinykh dove to the floor and opened the window blind. A layer of bright light lay on the ceiling, slightly illuminating the station. On the table they found crackers and salt, hospitably left by the previous crew - the Russian tradition, which is still practiced on the ISS. The on-board documentation was neatly secured on the shelves. Fans and other normally noisy devices were turned off. Savinykh recalls in his cosmic diary: “At that moment I had a feeling that I was in an old abandoned house. A terrible silence pressed on the ears. "[1]

Now, when the team and the Control Center evaluated the situation, they had to do something. The next morning, the crew woke up and received orders from the Earth: first of all, investigate the Spring, the drinking water storage system and check whether the water was frozen in it. The center strictly limited the astronauts on the subject of safety. Due to the lack of ventilation at the frozen station, astronauts' respiratory activity products accumulated around them, which could easily lead to carbon dioxide poisoning. Therefore, the Control Center allowed only one of the crew members to work inside, while the second one was supposed to monitor the state of his friend from the ship. Janibekov went first.

Earth: "Volodya, but if you spit, freezes or not?"

V. Dzhanibekov: “I do it immediately. Spat. And froze. Within three seconds.

Earth: "Is that you right on the porthole or where?"

V. Dzhanibekov: “No, on a thermoplate. Here rubber is frozen. She became like a stone, solid. "

Earth: "It does not inspire us."

V. Dzhanibekov: “And all the more of us ...”

Savinykh took his place and tried to drive the air through the airbags of the Spring.

V. Savinykh: “The scheme of“ Spring ”was collected. Pump docked. And the valves do not open. Where the air is, an icicle sticks out of the valve. ”

Earth: “Clearly, we temporarily stop working with“ Spring ”. We run to the other side. We need to understand how many "living" battery packs that can be reanimated ... We are preparing a proposal on how to get directly from these stations to the solar panels. In your free time, please see how the station’s batteries are oriented towards the Sun. ”

The problem with "Spring" was serious. The crew had enough water for 8 days - enough to stay at the station until June 14th. It was the third day of the flight. They could reduce water use to a minimum and take advantage of the Soyuz emergency water supply. If at the same time they were able to warm up a couple of packets of water from the station, they would be able to stretch their reserves until June 21, having won 12 more days to repair the station. [one]

Savinykh in the cold during the repair of "Salyut-7"

Photo epizodsspace.airbase.ru

Under normal conditions, battery recharging was controlled by an automatic system, whose operation also required electricity. The crew needed to find a way to supply electricity to the batteries. The easiest way to recharge them was to apply power from the Soyuz batteries, but the state of the station’s electrical system was not fully understood. If the wiring still had a closure, it could also disable the Soyuz electrical system, and then the astronauts would be cut off from the outside world. [one]

Instead, the management came up with a complex sequence of actions that the team had to perform. At first, they had to check the batteries for the opportunity to take charge. To their great joy, 6 out of 8 batteries seemed to be recoverable. Next, the team prepared the cables for connecting the batteries directly to the solar panels. In general, they needed to connect 16 wires, twisting their wires with their bare hands, in the cold. By connecting the wires, the team had to climb into the "Union" and use the engines of the orientation of the ship to change the spatial position so that the solar panels were turned to the Sun.

Earth: “We will spin around the Y axis using the Soyuz T-13 spacecraft's control system: so that the fourth battery is illuminated. Until the next communication session, you need to connect positive connectors on all good blocks, except the fourth one, we will not work with it anymore. Then we will spin and start feeding the first block. ”

V. Dzhanibekov: “We do it manually?”

Earth: "Yes, manually ... Pen in neutral position and extinguish the twist."

V. Savinykh: “Good.”

V. Dzhanibekov: "I am ready to work."

: « . , ».

. : «. . ».

: « ?»

. : « ».

: « . ».

. : «. : ».

: « : ».

. : « … … ».

. : « . , !»

: « , ».

. : «, !»

: « , ».

. , . (): « !»

: « ».

In his cosmic diary, the Savinykh writes: “It is this day that was the first joy, a spark of hope in the mass of problems, uncertainties, difficulties that Volodya and I had to solve.”

All this time, the astronauts did not know for sure whether they could stay at the station or the water supplies would run out earlier. They tried not to discuss the situation, focusing instead on work. After changing the spatial position and one day standby, five batteries were charged.

The crew disconnected them from their surrogate charging system and connected them to the station’s power grid. They turned on the light ... and, to their great relief, they saw that it was on fire.

Over the next few days, they worked on restarting the various onboard systems of the station. They turned on the ventilation and air regenerators, which gave them the opportunity to work at the station together. There was so much work that they spent the whole day at the station to return to the Soyuz and sleep with joy. [one]

On June 12, on the 6th day of the flight, the crew proceeded to replace the burnt communication system and check the water from the slowly warming Spring to be contaminated.

On June 13, on the 7th day of the flight, the crew continued to work on the communication system and by noon Moscow time, the Control Center reestablished communication with the station. They also checked the automatic docking system, realizing that if it did not pass the test, they would have to go home. The station needed provisions, which could only be delivered in large quantities by cargo ships, which could not be operated manually, like the Soyuz. Fortunately, the test was successful and the astronauts continued their mission.

And finally, on June 16, on the 10th day, when the stocks were already 2 days old as they should have ended, the performance of the Spring was fully restored. The moment came when the station had enough working systems and supplies to continue the operation. [one]

Janibekov and Savinykh report from the recently restored Salyut-7.

Photo epizodsspace.airbase.ru

Rest of the story

The reason why the station plunged into the cold darkness turned out to be a malfunction of a single sensor, which monitors the state of charge of the 4th battery. He was programmed to disconnect from the recharging system as soon as the battery with which he worked became fully charged, preventing its overcharging. Each of the seven main and one backup batteries had such sensors and any of them, regardless of whether it was the main one or the backup one, had the right to turn off the recharging system. [3]

At some point after the loss of communication with the station, the sensor of the 4th battery began to fail. He sent signals that the battery was charged even in cases where it was not. Once a day, when the on-board computer sent a command to charge the batteries, the 4th battery sensor immediately stopped this process. In the end, the onboard systems took all the energy they had from the batteries and the station slowly began to freeze. If communication with her were not interrupted, operators could intervene and block the faulty sensor. However, in the absence of communication, it was impossible to say when he refused. [3], [12]

Janibekov stayed at the station for 110 days. He returned home on the Soyuz T-13 with Georgy Grechko, who flew to the station with Vladimir Vasutin and Alexander Volkov on the Soyuz T-14 in September 1985. Vasyutin, Volkov and Savinykh remained on board for a lengthy operation, which, however, was interrupted ahead of schedule in November, when Vasyutin fell ill and this caused them to immediately return to Earth.

On February 19, 1986, the base module of the Salyut-7 successor, Mir station, was launched. Despite the fact that the replacement "Salute-7" was already in orbit, its role in the Soviet space program has not yet come to an end. The first crew who went to Mir did something unprecedented. After arriving at Mir and performing preliminary operations to launch the station, they boarded the Soyuz and set off for Salyut-7. It was the first and only in the history of flight crew from one station to another. There they completed the work that the crew of the Soyuz T-14 left unfulfilled, after which they returned to Mir to return to Earth in the future.

The Soviet Union hoped to continue using the Salyut-7 even after Soyuz T-15 left it, therefore, in order to save the station, it was placed in a high orbit. However, with the collapse of the Soviet and then the Russian economy, plans to finance future flights to the Salyut-7, with the help of the Soyuz ships or being in development of the Buran shuttles, did not materialize. The station slowly lost its orbit until control was lost and it entered the atmosphere over South America in 1991. [7]

Despite the fact that the station as such is no longer present, its legacy in the form of triumph over the vicissitudes of fate remains with us. Of the entire series of Salyut, the seventh issue has probably gone through the most serious tests in their entire history. However, while the other stations were lost, the skill and determination of the designers, engineers, control operators and cosmonauts of the Salyut-7 kept him in flight. This spirit lives to this day on the International Space Station, which has been in orbit for more than 15 years. She also experienced system failures, coolant leaks and other problems, but also, like their predecessors who worked on Salyut-7, modern designers, engineers, flight operators, astronauts and astronauts continue to fly with the same determination.

Original author -NickolaiB is now on Habré!

References

- Savinykh V.P. Notes from the Dead Station. - M .: Publishing House "Systems Alisa", 1999. < militera.lib.ru/explo/savinyh_vp/index.html >

- V.E. Gudilin, L.I. Slabky. SPACE ROCKET SYSTEMS. (History. Development. Perspectives). Moscow 1996. < www.buran.ru/htm/gudilin2.htm >

- . « , .» « » 1985, №11, . 33-40, 4 . on < epizodsspace.no-ip.org/bibl/n_i_j/1985/11/letopis.html >

- Portree, David S. F… Mir hardware heritage. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1995. Print. Web. < ston.jsc.nasa.gov/collections/TRS/_techrep/RP1357.pdf >

- . ., . . « ». , 1986, 4. < epizodsspace.no-ip.org/bibl/nauka-v-ussr/1986/remont.html >

- «Soyuz T-13.» Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 21 Apr. 2014. Web. < en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soyuz_T-13 >

- Mcquiston, John. «Salyut 7, Soviet Station in Space, Falls to Earth After 9-Year Orbit.» The New York Times. The New York Times, 6 Feb. 1991. Web. < www.nytimes.com/1991/02/07/world/salyut-7-soviet-station-in-space-falls-to-earth-after-9-year-orbit.html >

- .. «-7» , 2013, 27: 18-22. [ 26 2014] < www.ergo-org.ru/newsletters.html >.

- .. ( 4- .) — .: , 1999. < militera.lib.ru/explo/chertok_be/index.html >

- ., ., . « — ». , 1987, №10(2565).< www.vokrugsveta.ru/vs/article/3714 >.

- Canby, Thomas Y. «Are the Soviets Ahead in Space?» National Geographic 170.4 (1986): 420-59. Print.

- . . « — — .» — .: , 2002. < epizodsspace.airbase.ru/bibl/savinyh/vbk/obl.html >

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/215627/

All Articles