Are high-frequency traders too slow?

High Frequency Trading (High Frequency Trading, HFT) is an excellent object to learn, because so far there is no consensus in the world about its pros and cons. Therefore, scientists and practicing traders may continue to write articles about why he is bad or, on the contrary, good, and at the same time some statements will not contradict others, since the authors of articles often use different rating systems. However, even if you have decided on the object of evaluation, it is usually very difficult to measure, not to mention commenting on the results of measurement.

Not so long ago, the Working Report of the European Central Bank on high-frequency trading by Jonathan Brogaard, Terrence Hendershott and Ryan Riordan * fell into my hands. They gave high-frequency trading mainly positive assessments, and this attracted public attention. In their opinion, the criteria for evaluating HFT lie in answering the questions: “Does high-frequency trading simplify the search for [current] market prices?” And “Does high-frequency trading provide liquidity?” - it seems to me that if they thought HFT is evil, then would ask about something else. But they answer “Yes” to their questions: according to the results of their research, high-frequency trading simplifies the search for current market prices and does not cause instability due to a decrease in liquidity in the period of high market volatility.

')

If you like to make jokes about scientific articles, it's time to do it - I honestly do not know what else you can do after reading this work. The term “simplifies the search for prices” is followed by a serious explanation “by speeding up the search by three or four seconds” after price information appears on the market. This means that high-frequency trading makes markets three seconds more efficient. Is it good? This is a question from the field of metaphysics, so we will lower it to the level of notes **.

You can make a joke about instability, but also slightly lower ***.

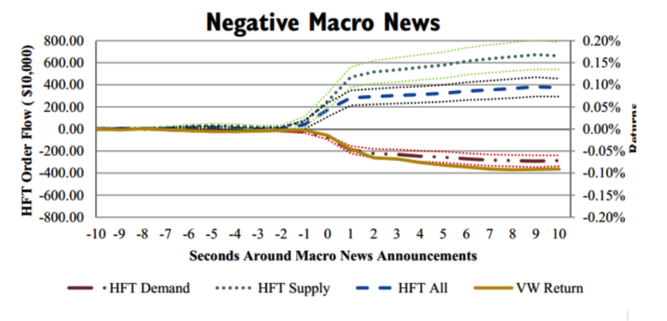

But there is one oddity. The authors analyzed the state of the market after the appearance of negative macroeconomic news and built the following chart:

What happens: about a second before the appearance of bad news, high-frequency trading companies are actively selling (that is, they form a demand for liquidity to sell shares - this is indicated by a red dotted line). At about the same time, stock prices are starting to fall (gold line, see axis Ox). In this case, somewhere for two seconds before the news, HFT companies passively buy . Thus, they form the supply of liquidity: companies give commands to sell and buy, after which the price of the offer increases. This is indicated by gray, green, blue, and God knows what points. The blue dotted line is the “net” result of HFT firms. It turns out that companies engaged in high-frequency trading buy more news than they sell, and, apparently, lose money on it.

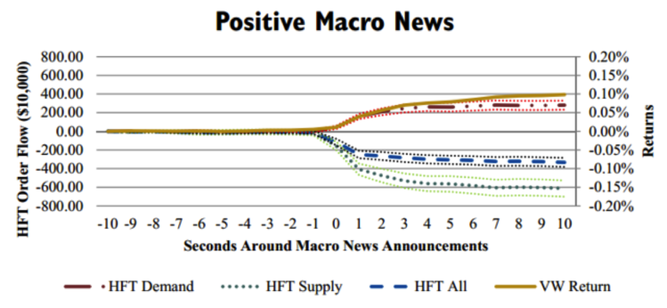

The exact opposite happens when positive news arrives: in such a situation, HFT companies sell more than they buy and lose money again. As in the case of bad news, the price changes, and the demand for liquidity of HFT firms lags behind their supply of liquidity by about a second:

This generally corresponds to the opinion of the authors of the report on high-frequency traders as market players providing high liquidity - in fact, HFT companies act as market makers in this case, taking the side opposite to the majority - but here are the time calculations presented in the charts seem very strange. According to this interpretation, the reaction of HFT companies to a particular news lags behind the market’s actions by a full second, which is why these firms have to incur losses. Their commands to buy and sell stocks do not change for some time after the news appears, while someone receives this news a little earlier **** - and begins to enrich themselves at the expense of high-frequency traders.

It turns out that an important advantage of high-frequency traders can take advantage of other players who are slightly faster than HFT companies.

Strange isn't it?

However, in essence, it is. The term “high-frequency traders” refers to 26 large independent HFT companies from the Nasdaq list that do not include large brokers / dealers, such as Goldman, which uses high-frequency trading strategy, as well as private companies working in the field of algorithmic trading: trade quickly, but do not have a steady income from trading operations. These firms are more likely to respond to important news than large HFT companies, whose trading strategies are usually based on statistics on buying and selling securities (information on prices and order portfolios), rather than current news reports. *****. Therefore, fast algorithmic traders in such situations successfully beat in this particular case-slightly-less-high-frequency high-frequency traders.

What is the conclusion? Well, firstly, if in your understanding “high-frequency traders” are “everyone who sells and buys very quickly with the help of computer programs,” then you are unlikely to like the conclusions regarding HFT companies contained in the above-mentioned report. They relate to one single category of high-frequency traders - since other high-frequency traders trade against them. If, according to this report, traders from the first category are good, then the rest (high-frequency traders playing against them) are bad. Average estimates for the entire group here are quite difficult to give.

By the way, we [Bloomberg] have already written about attempts to limit the possibilities of various kinds of “high-speed” traders who receive economic information a millisecond earlier than the rest of the market players. At that moment, these attempts led me into confusion, since, in fact, they should not protect individual investors, but another, slightly less rapid category of “high-speed” traders. If the news becomes known at 14:00, and you [your computer] receives it at 13: 59: 59.999, and you are trying to buy shares based on your information advantage, then the only market player who can sell you shares at 14:00: 00.006, there will be another computer. A trader, or portfolio manager at Fidelity, or any other person at this moment will still run over the news lines, lagging behind computers for many seconds and therefore remaining completely safe .

So here. People who are beaten up by “high-frequency traders” in the broad sense of the word when news arrives are themselves “high-frequency traders” - in the narrow sense. Algorithmic market makers are left with a nose because of algorithmic speculators. And all this financial-market drama unfolds in the blink of an eye - so all you need to avoid is just to blink.

* Like many other ideas in near-financial scientific circles, this has been “on the Internet” for some time (taking various forms), but was ultimately expressed in the “quasi-declaration” of the European Central Bank. The Central Bank is an important and significant organization, so today we are talking about this document.

** Quote from the document itself:

From the fact that HFT companies predict price movements for the next few seconds, it does not follow that this information inevitably becomes public. Perhaps high-frequency traders are competing with each other for the possibility of obtaining optional public information and using it to predict price behavior. If high-frequency traders did not exist, it would be unknown how such information (in the absence of a player with a similar role) transforms into prices. The main difficulty is how to determine what information is public and how it is transformed into prices, that is, what are the incentives for investing in the acquisition of information (Grossman and Shtiglitz, 1980).

You are probably interested in what such fundamental research is conducted by high-frequency traders in order to learn new information and make it public.

As part of a mental experiment [and an answer to a question - commentary on translation], it is possible to think about what would happen if high-frequency traders were blocked from accessing economic news for three seconds - would their three-second advantage remain over “non-high-speed” market players? And if it were not three seconds, but five minutes?

*** The authors tracked the behavior of high-frequency traders during the top 10% of the most volatile days, compared it with the remaining 90% of the most volatile days, and found that high-frequency traders maintain an approximately equal level of liquidity of securities. The probable model of forming a strategy for high-frequency traders can be expressed by the words “volatility is profitable, but blind panic is not”, which means that you actively provide liquidity supply for 90–99.5% days, and significantly reduce activity in the remaining 0.5% days . Such a model can lead to sudden drops in the market about once a year (rather than once every two weeks) —that is, in essence, what happens, but the Central Bank document examines the behavior of high-frequency traders within the top 10% of moderately volatile days.

**** And what happens before the news becomes known? The authors use timestamps from Bloomberg to determine the "zero" second (the moment when the news becomes known to all) - you can bet that the true moment of the news release is -1-second, and then it takes some time for the news to reach Company Bloomberg, however, the start of trading 2 seconds before the publication of the news would look frankly strange.

***** For this thought, I owe a conversation with Terrence Hendershott, one of the authors of the document. By the way, if you believe that high-frequency traders react only to market prices and teams, and not to fundamental news, then the statement of Grossman-Stieglitz in a footnote ** moves to an absolutely metaphysical plan.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/214097/

All Articles