An important step has been taken towards laser fusion.

On Wednesday, February 12, an article was published in Nature magazine describing the results of recent experiments at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) installation of the Livermore National Laboratory, during which for the first time energy output due to laser-controlled thermonuclear reaction exceeded the amount of energy transferred to fuel. The pressure and temperature required to initiate nuclear fusion are achieved in the NIF setup with the help of 192 lasers, which simultaneously irradiate a tiny target of frozen deuterium and tritium.

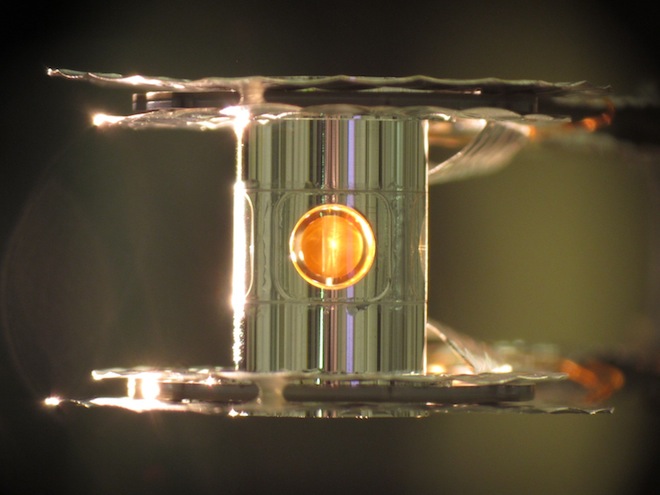

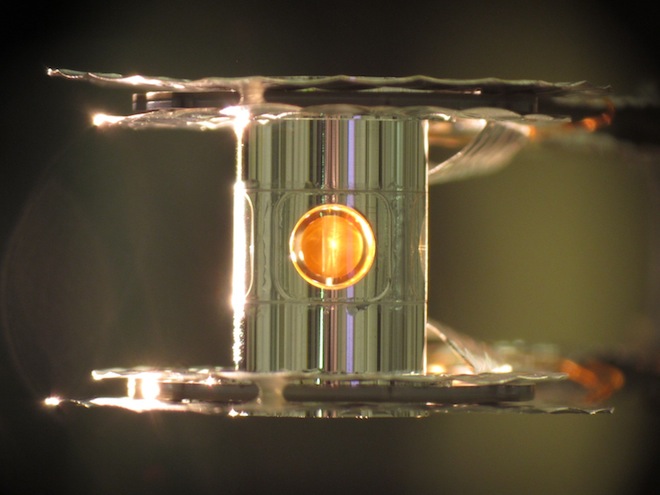

The target is a ball with a diameter of 2 mm, the outer layer of which is made of plastic, and the inner one is made of heavy isotopes of hydrogen. The ball is located inside a golden cylinder with holes through which laser radiation comes in. Under the influence of this radiation, the inner walls of the cylinder begin to emit X-rays, which evenly “fry” the target from all sides. Its outer shell instantly evaporates and squeezes the fuel to a pressure of 100 million atmospheres with tremendous force. All this happens in a few nanoseconds. Peak laser flash power reaches 500 terawatts.

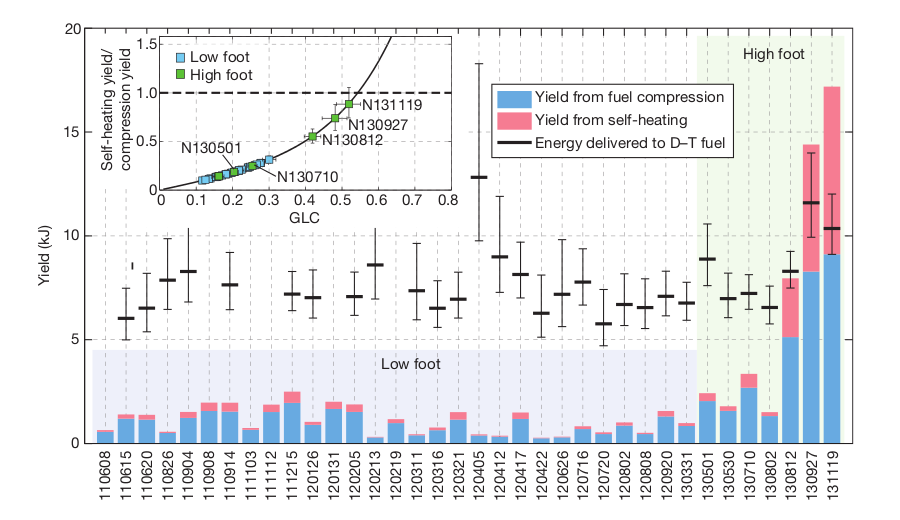

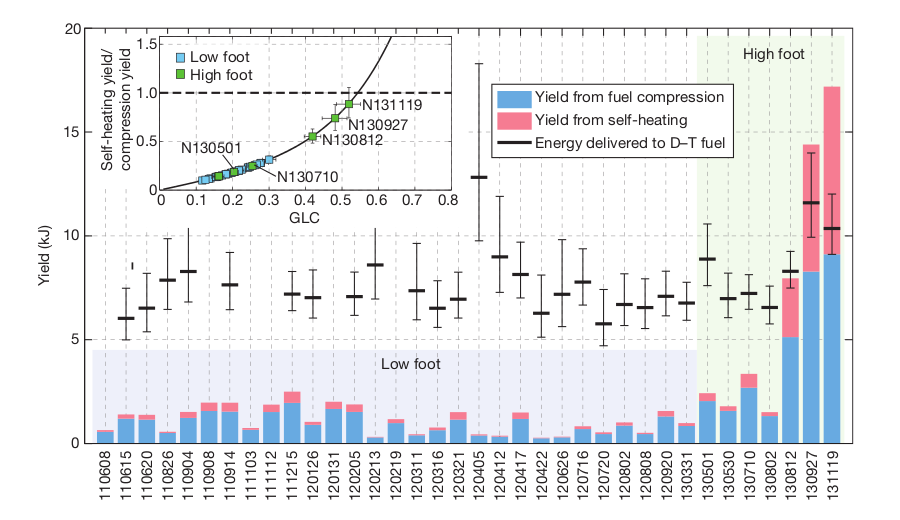

Until now, physicists could not get more energy from a thermonuclear reaction than was transferred to the fuel, mainly due to the fact that during compression the fuel was mixed with the shell material. Since not one laser pulse is used for compression, but several, varying the duration and power of individual flashes, it is possible to control this process. In the latest experiments conducted in the fall of 2013, we managed to pick up a sequence of pulses that provides stable compression and reduces contamination of the fuel with atoms of the shell. September 27, 2013 managed to get 14 kilojoules of energy, spending on compression and heating of the fuel about 12 kJ. November 13 - 17 kJ at a cost of 10 kJ. At the beginning of 2014, the ratio of energy produced to fuel consumed was increased to 2.6.

')

Although these results are an important milestone on the path to thermonuclear energy, it is still very far from practical application. The fact is that the total energy consumption of the installation per pulse is two orders of magnitude greater than the amount of energy that comes to the capsule with the fuel. Economic efficiency is still many times lower - while there is no self-sustaining synthesis reaction, NIF is a purely experimental setup; it can take no more than one “shot” in a few hours.

The project of the International Experimental Nuclear Reactor (ITER) , which is currently under construction in France, still looks more practical - the start of experiments on it is planned for 2020, and the developed thermonuclear power should be 500 megawatts. The ITER reactor is a huge tokamak - the thermonuclear reaction in it takes place in a toroidal chamber inside a plasma “cord” held by a magnetic field. In total, about 300 tokamaks have been built in the world, experiments with them have been carried out for several decades. Pulse-type installations, which include NIF, are much less common.

The target is a ball with a diameter of 2 mm, the outer layer of which is made of plastic, and the inner one is made of heavy isotopes of hydrogen. The ball is located inside a golden cylinder with holes through which laser radiation comes in. Under the influence of this radiation, the inner walls of the cylinder begin to emit X-rays, which evenly “fry” the target from all sides. Its outer shell instantly evaporates and squeezes the fuel to a pressure of 100 million atmospheres with tremendous force. All this happens in a few nanoseconds. Peak laser flash power reaches 500 terawatts.

Until now, physicists could not get more energy from a thermonuclear reaction than was transferred to the fuel, mainly due to the fact that during compression the fuel was mixed with the shell material. Since not one laser pulse is used for compression, but several, varying the duration and power of individual flashes, it is possible to control this process. In the latest experiments conducted in the fall of 2013, we managed to pick up a sequence of pulses that provides stable compression and reduces contamination of the fuel with atoms of the shell. September 27, 2013 managed to get 14 kilojoules of energy, spending on compression and heating of the fuel about 12 kJ. November 13 - 17 kJ at a cost of 10 kJ. At the beginning of 2014, the ratio of energy produced to fuel consumed was increased to 2.6.

')

Although these results are an important milestone on the path to thermonuclear energy, it is still very far from practical application. The fact is that the total energy consumption of the installation per pulse is two orders of magnitude greater than the amount of energy that comes to the capsule with the fuel. Economic efficiency is still many times lower - while there is no self-sustaining synthesis reaction, NIF is a purely experimental setup; it can take no more than one “shot” in a few hours.

The project of the International Experimental Nuclear Reactor (ITER) , which is currently under construction in France, still looks more practical - the start of experiments on it is planned for 2020, and the developed thermonuclear power should be 500 megawatts. The ITER reactor is a huge tokamak - the thermonuclear reaction in it takes place in a toroidal chamber inside a plasma “cord” held by a magnetic field. In total, about 300 tokamaks have been built in the world, experiments with them have been carried out for several decades. Pulse-type installations, which include NIF, are much less common.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/212489/

All Articles