On the Poincare conjecture. Lecture in Yandex

As early as the 19th century, it was known that if any closed loop lying on a two-dimensional surface can be pulled together into a single point, then such a surface can easily be turned into a sphere. Thus, the surface of the balloon can be transformed into a sphere, but the surface of a donut is not (it is easy to imagine a loop that does not pull into one point in the case of a bagel). The hypothesis expressed by the French mathematician Henri Poincare in 1904, states that a similar statement is true for three-dimensional manifolds.

Poincaré managed to prove the hypothesis only in 2003. The proof belongs to our compatriot Grigory Perelman. This lecture sheds light on the objects necessary to formulate a hypothesis, the history of the search for evidence and its main ideas.

')

Lecturers of the Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics of Moscow State University give a lecture to them. n Alexander Zheglov and Ph.D. n Fedor Popelensky.

If you do not go into mathematical details, then the question posed by the Poincare hypothesis can be as follows: how to characterize the (three-dimensional) sphere? In order to properly understand this question, you need to get acquainted with one of the most important concepts in topology — the homeomorphism. Having dealt with it, we will be able to precisely formulate the Poincaré hypothesis.

In order not to get into the mathematical details of a formal definition at all, we will say that two figures are considered homeomorphic if it is possible to establish such a one-to-one correspondence between the points of these figures such that the close points of one figure correspond to the close points of another figure and vice versa. The details we have missed consist precisely in the adequate formalization of the proximity of points.

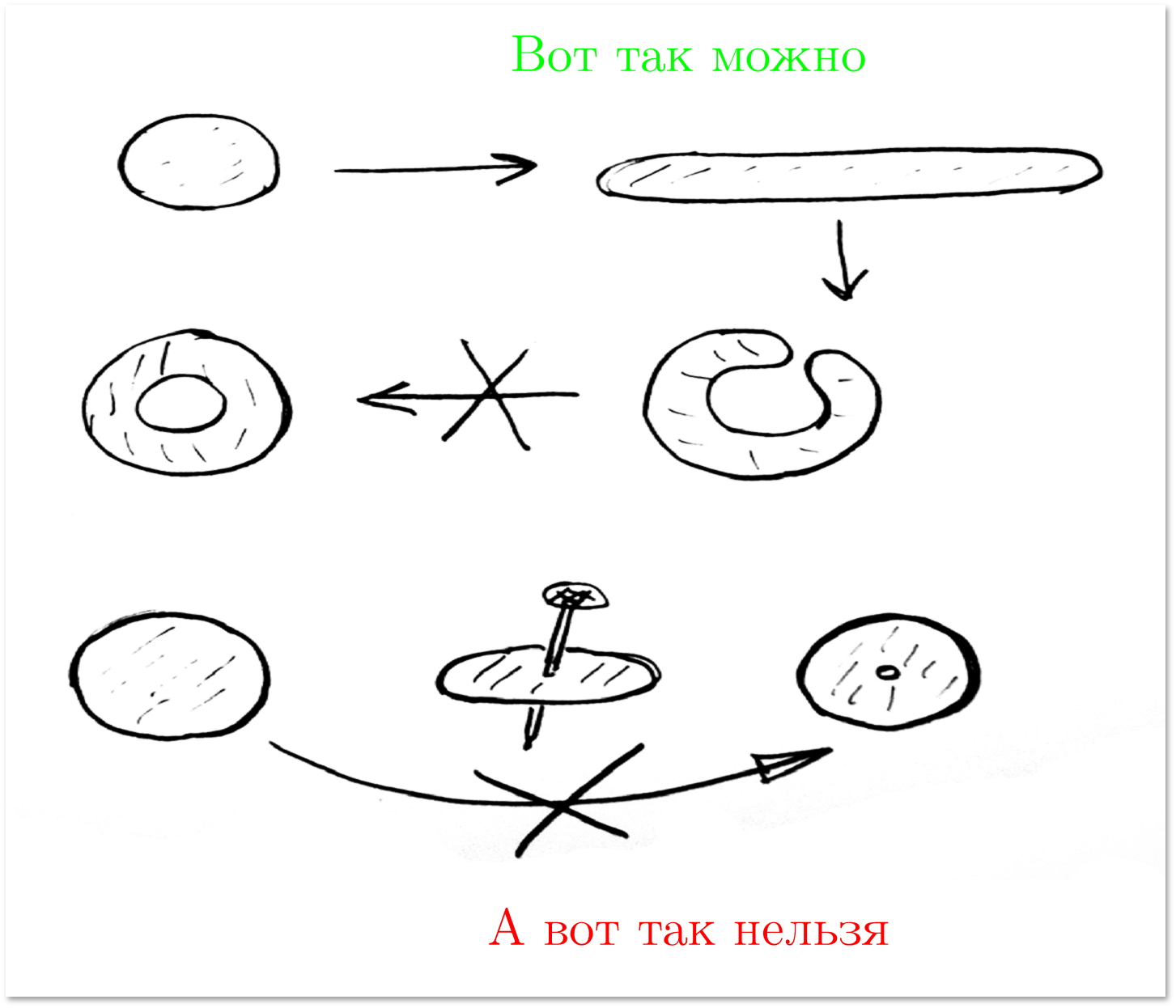

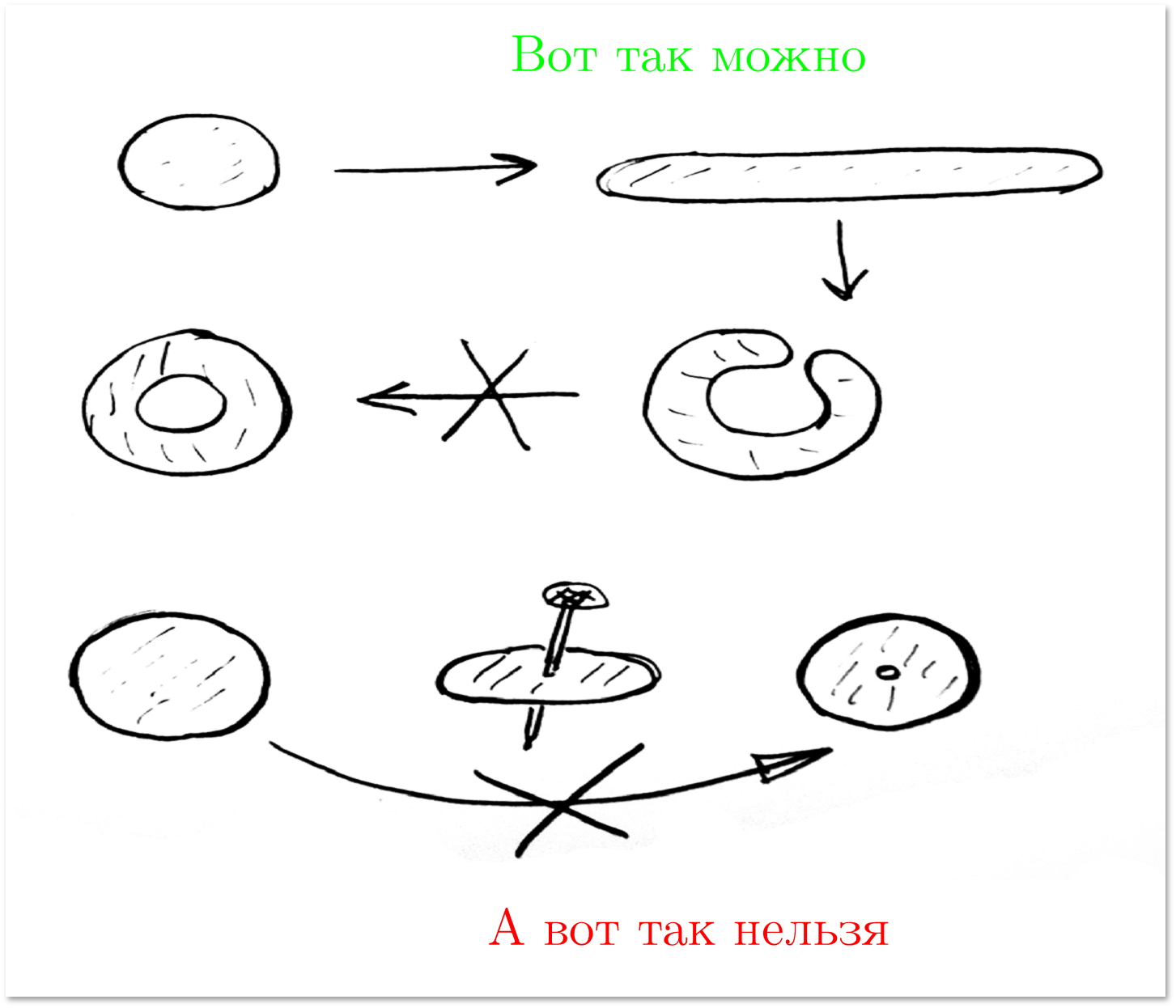

It is easy to understand that two figures are homeomorphic if one of the other can be obtained by an arbitrary deformation, under which it is forbidden to “spoil” the surfaces (tear, crush areas to a point, make holes, etc.).

For example, to get a hemisphere from a disk, as shown in the picture above, we just need to click on top of its center, holding the outer rim. One can imagine that the surfaces are made of perfect rubber, so that all the figures can contract and stretch as they please. You can not do only two things: tear and glue.

We will have a more accurate (but still not final in terms of severity) idea of homeomorphic figures if we allow another operation: you can make a cut on the figure, twist, tie, untie, etc., but then you must seal the cut as It was.

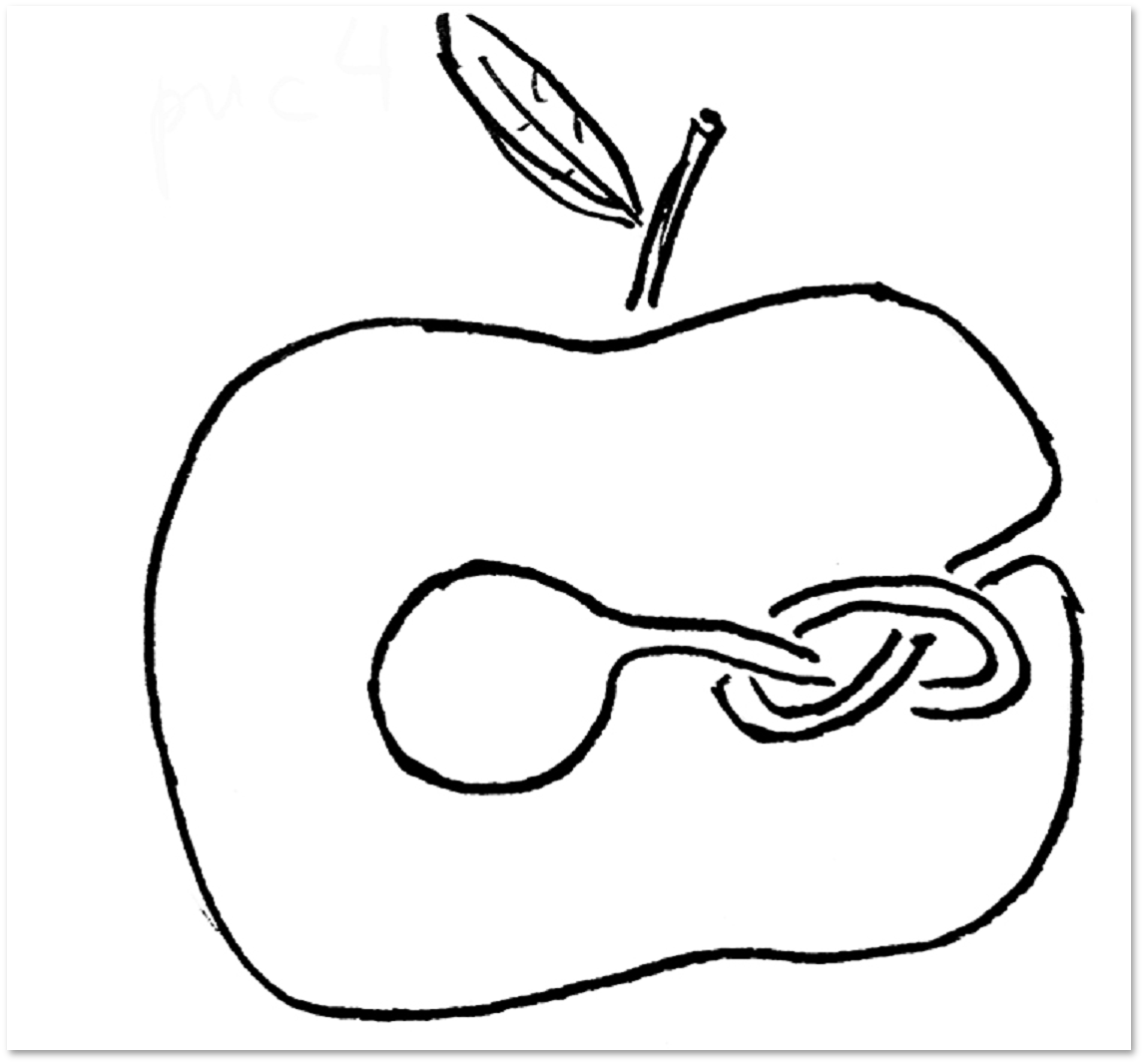

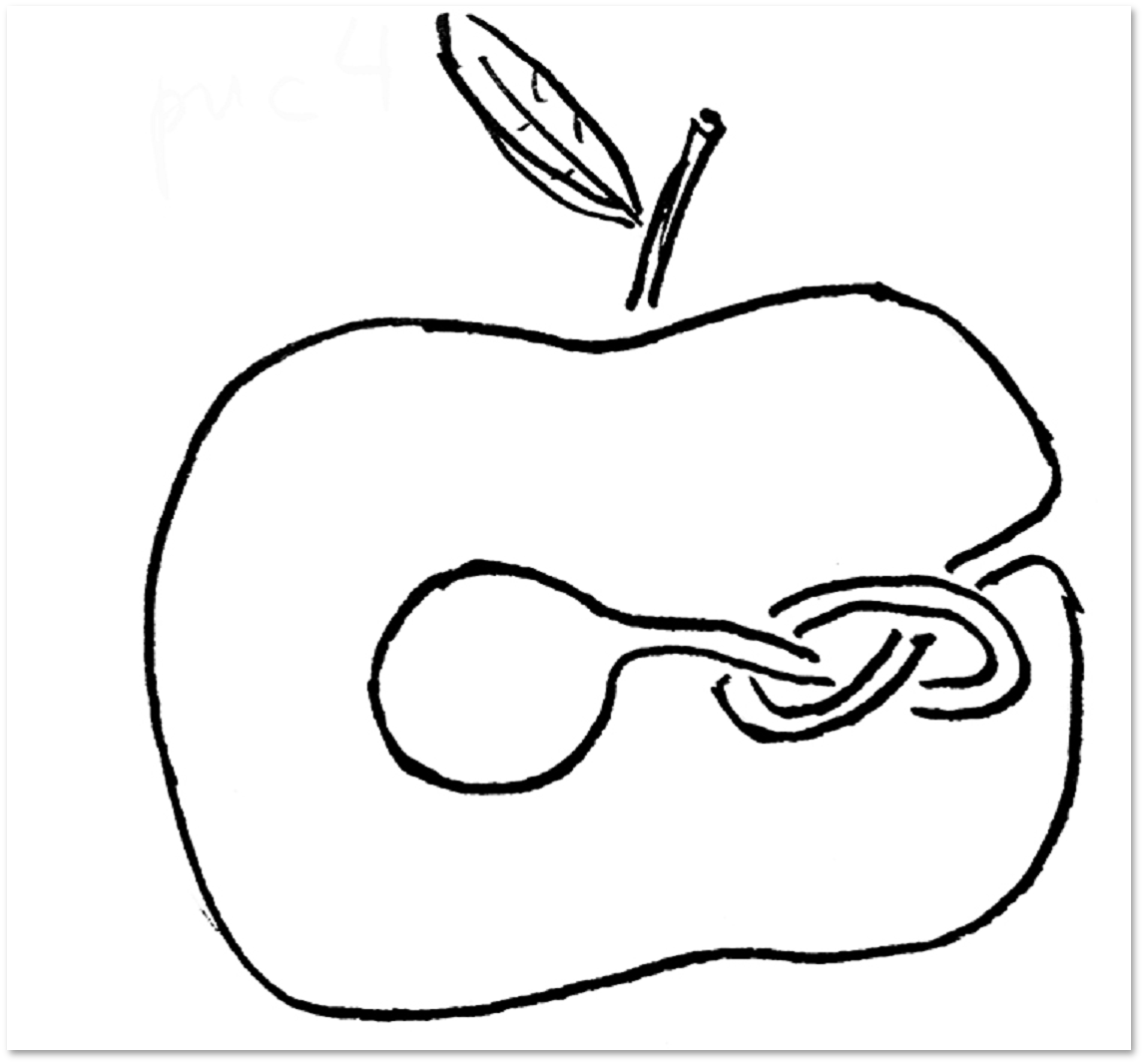

Let's give one more example. Imagine an apple in which a worm gnawed a knot and a small cave.

From the point of view of topology, the surface of this apple will still remain a sphere, since if we pull it all off in a certain way, we get the surface of the apple in the same way it was before the worm began to eat it.

To consolidate, try to classify the letters of the Latin alphabet to within a homeomorphism (that is, find out which letters are homeomorphic and which are not). The answer depends on the type of letters (on the type of the font or on the typeface), and for the simplest version of the style it is shown in the following figure:

Of the 26 letters we get only 8 classes.

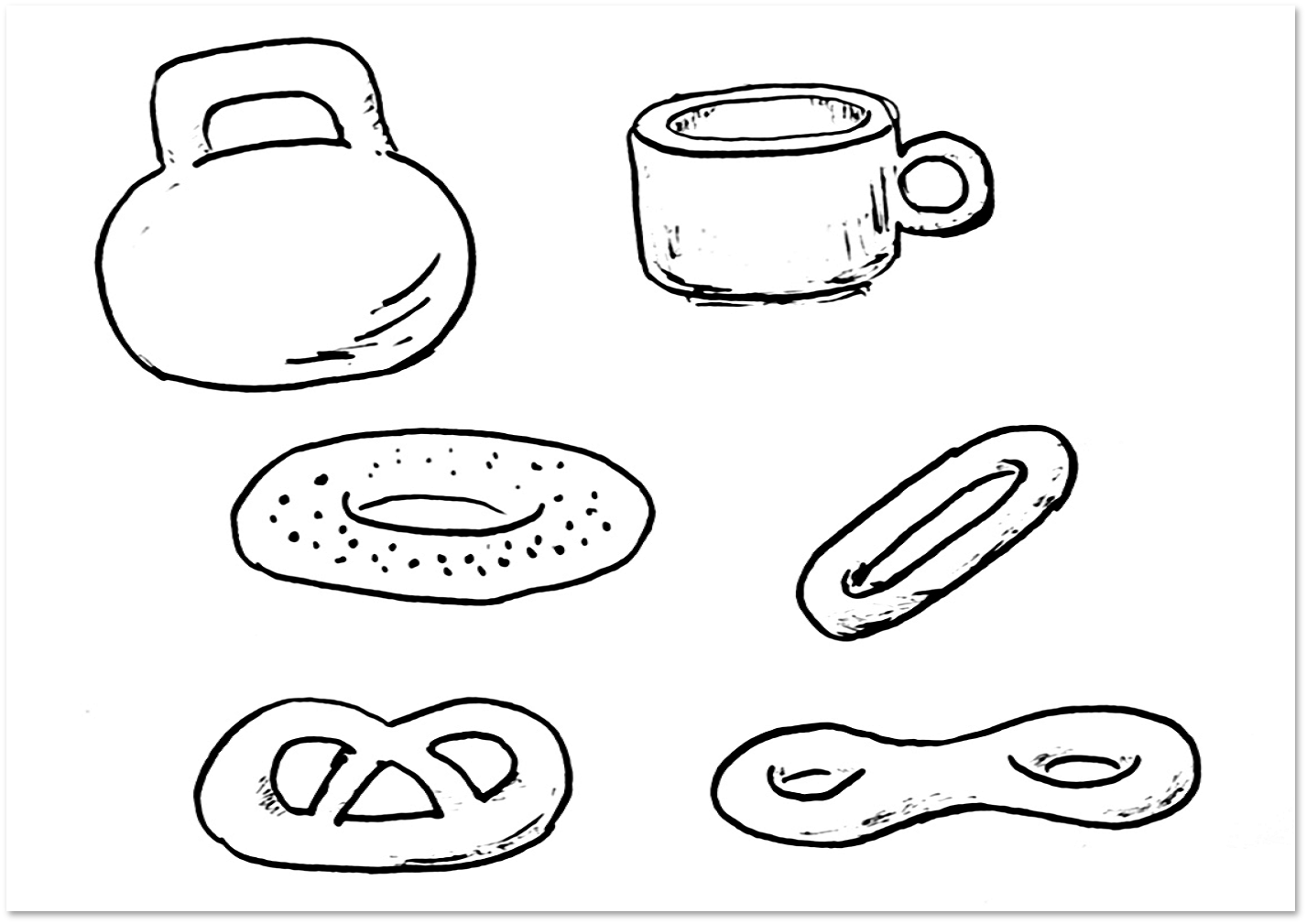

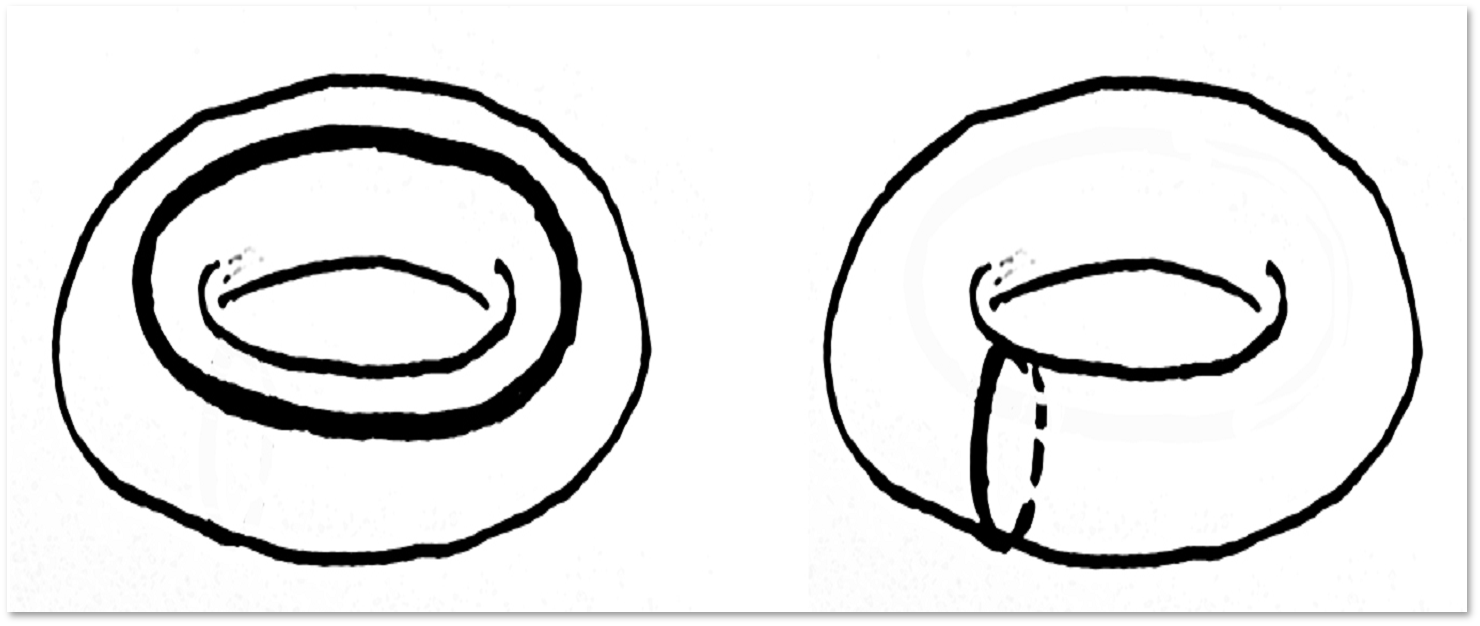

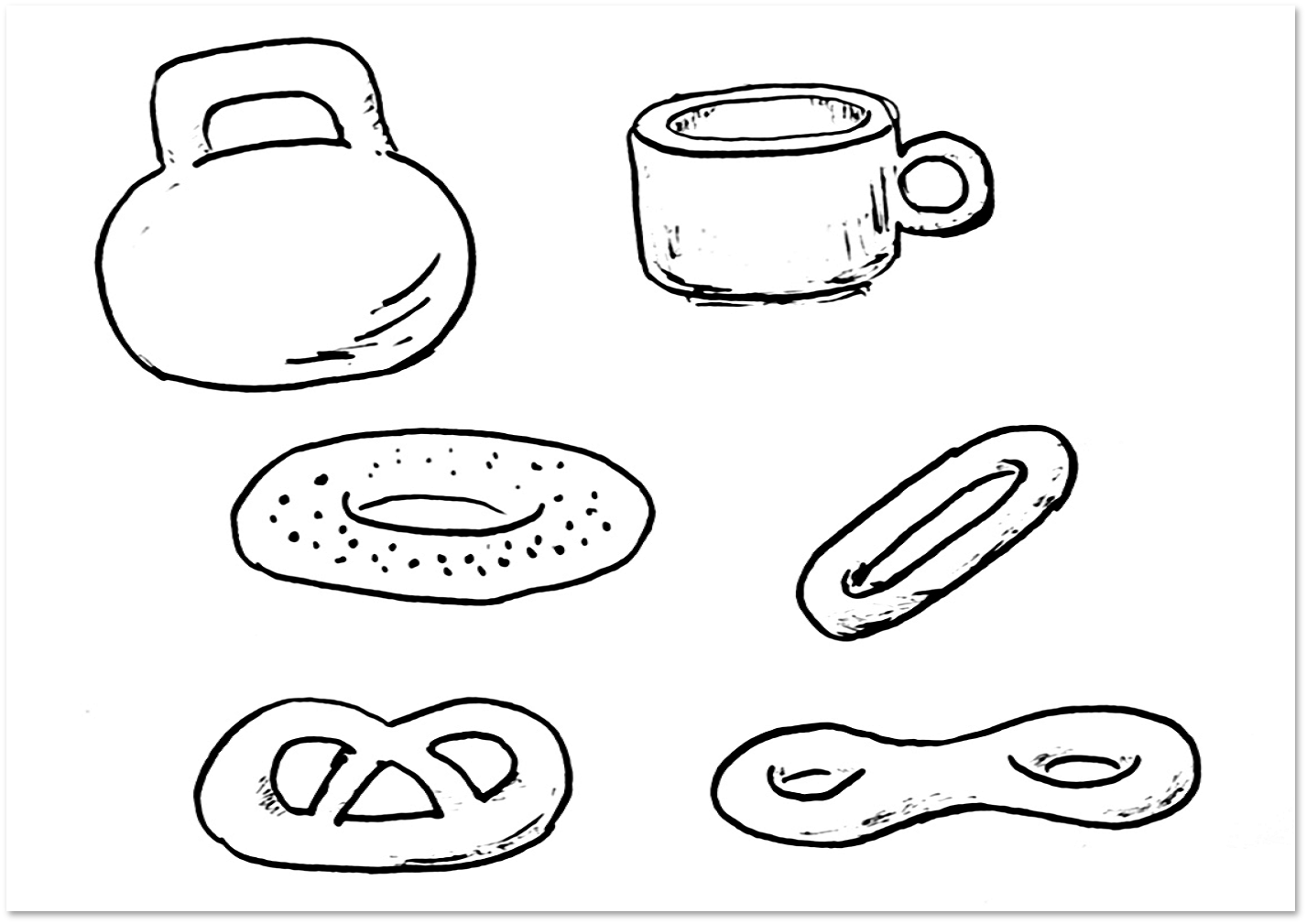

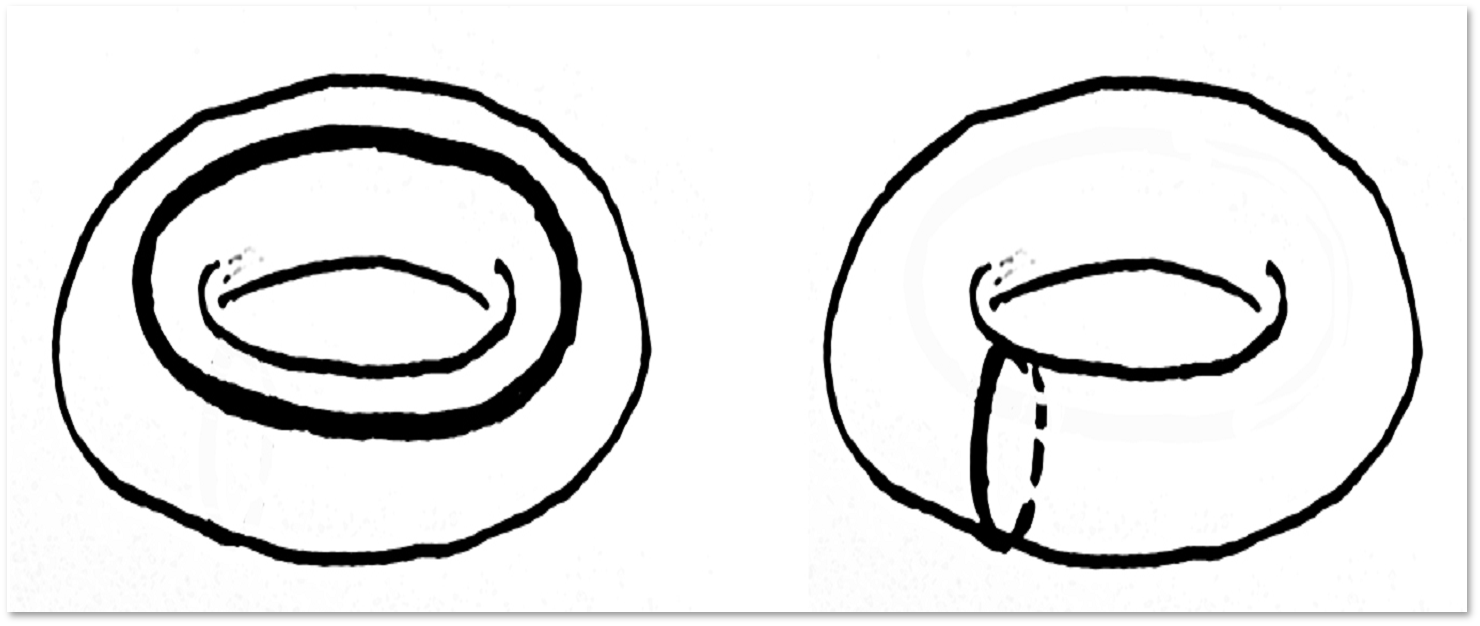

The following picture shows the weight, coffee cup, bagel, dryer and pretzel. From a topological point of view, the surface of the weight, coffee cup, bagel and drying are the same, i.e. homeomorphic. As for the pretzel, it is shown here for comparison with the surface, which in the topology is often called a pretzel (it is depicted in the lower right corner of the picture). As you probably already understand, both the topological pretzel and the edible pretzel are different from the torus.

Let M be a closed connected manifold of dimension 3. Let any loop on it be pulled to a point. Then M is homeomorphic to a three-dimensional sphere.

The greatest difficulty for an unprepared person here is the notion of “variety of dimension 3” and properties expressed by the words “closed” and “connected”. Therefore, we will try to deal with all these concepts and properties using the example of dimension 2, in this case much is radically simplified.

Let M be a closed connected surface (a manifold of dimension 2). Let any loop on it be tied to a point. Then the surface M is homeomorphic to a two-dimensional sphere.

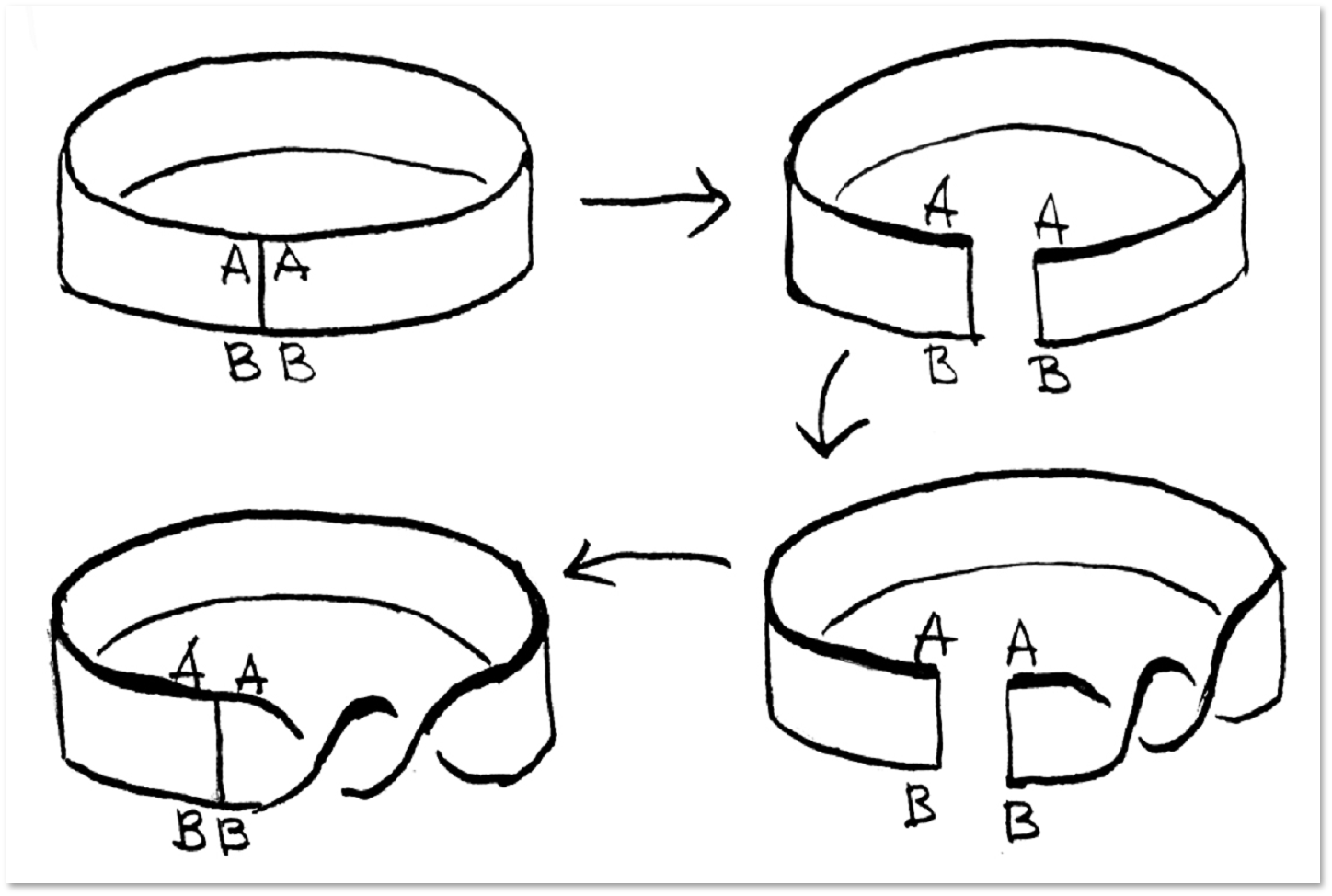

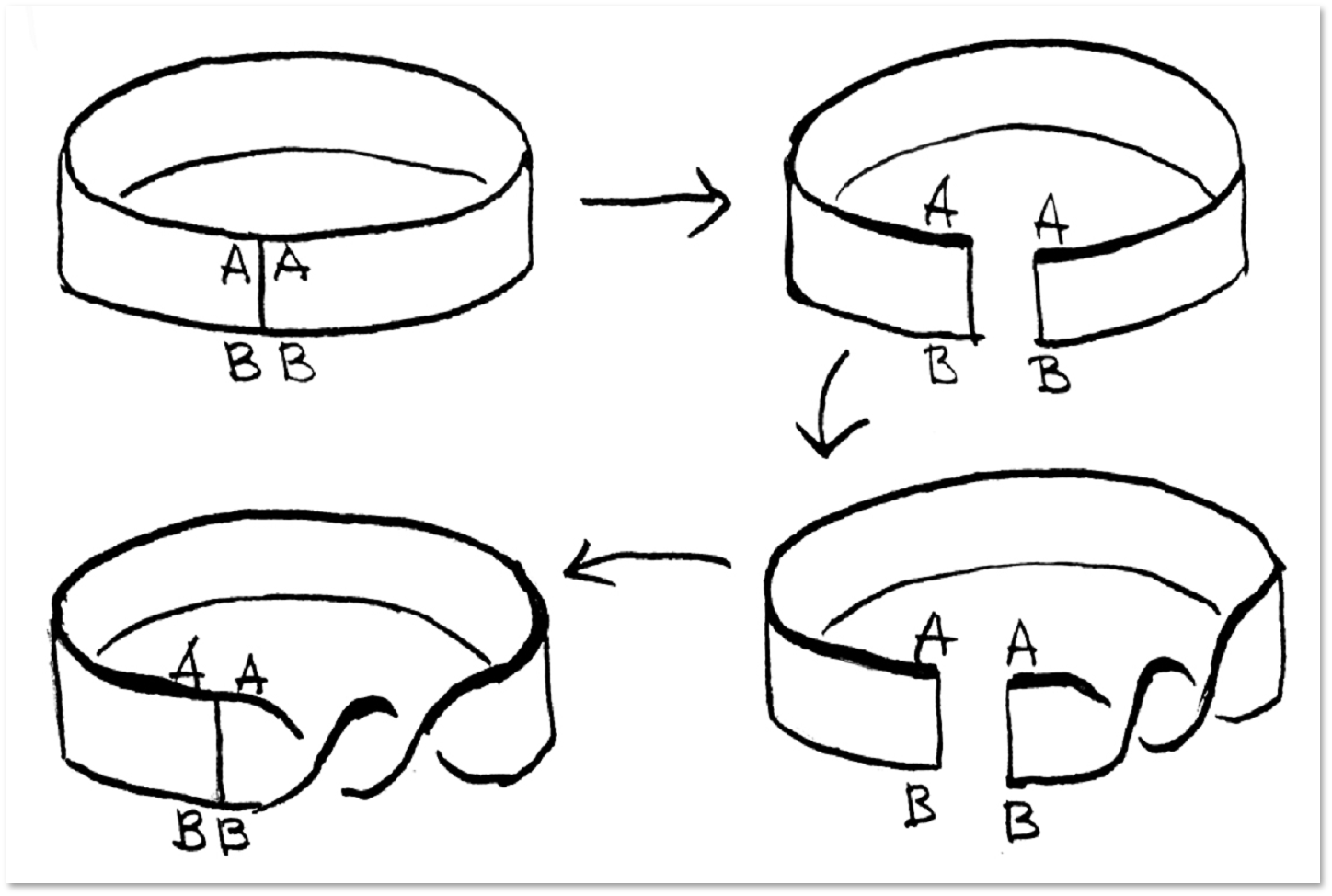

First, we define what a surface is. Take a finite set of polygons, divide all their sides (edges) into pairs (i.e. all sides of all polygons should have an even number), in each pair we choose which of the two possible ways we can glue them together. We glue. As a result, a closed surface is taught.

If the resulting surface consists of one piece, and not several separate ones, then they say that the surface is connected. From a formal point of view, this means that after pasting from any vertex of any polygon, one can go along edges to any other vertex.

Here is a simple example: if we assume that in the picture above all the triangles are correct, then after gluing together we should have a regular tetrahedron, the surface of which is also homeomorphic to a sphere.

Formally, it is necessary to require that from any vertex of any polygon after gluing it is possible to pass to any vertex of any polygon (along the edges).

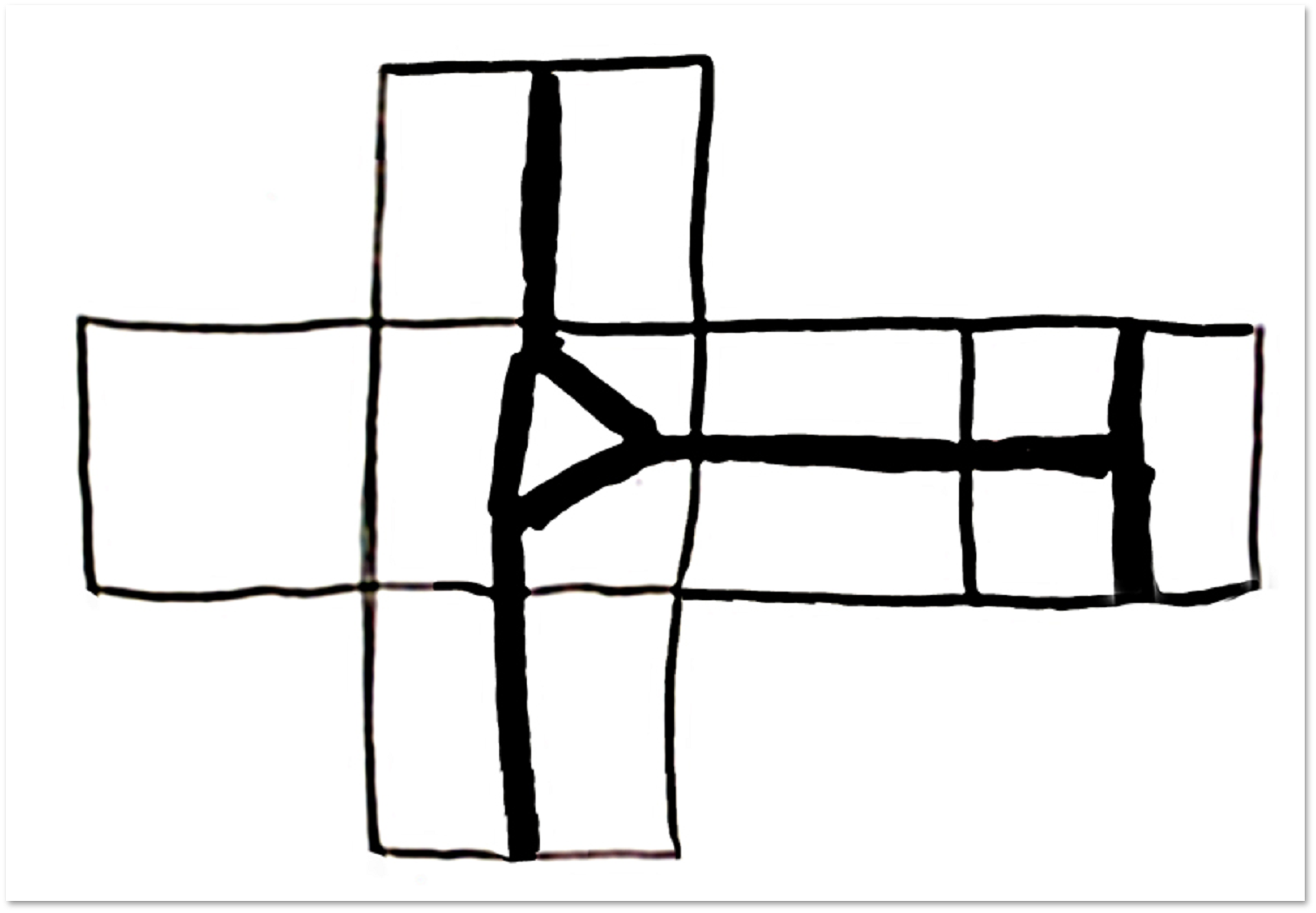

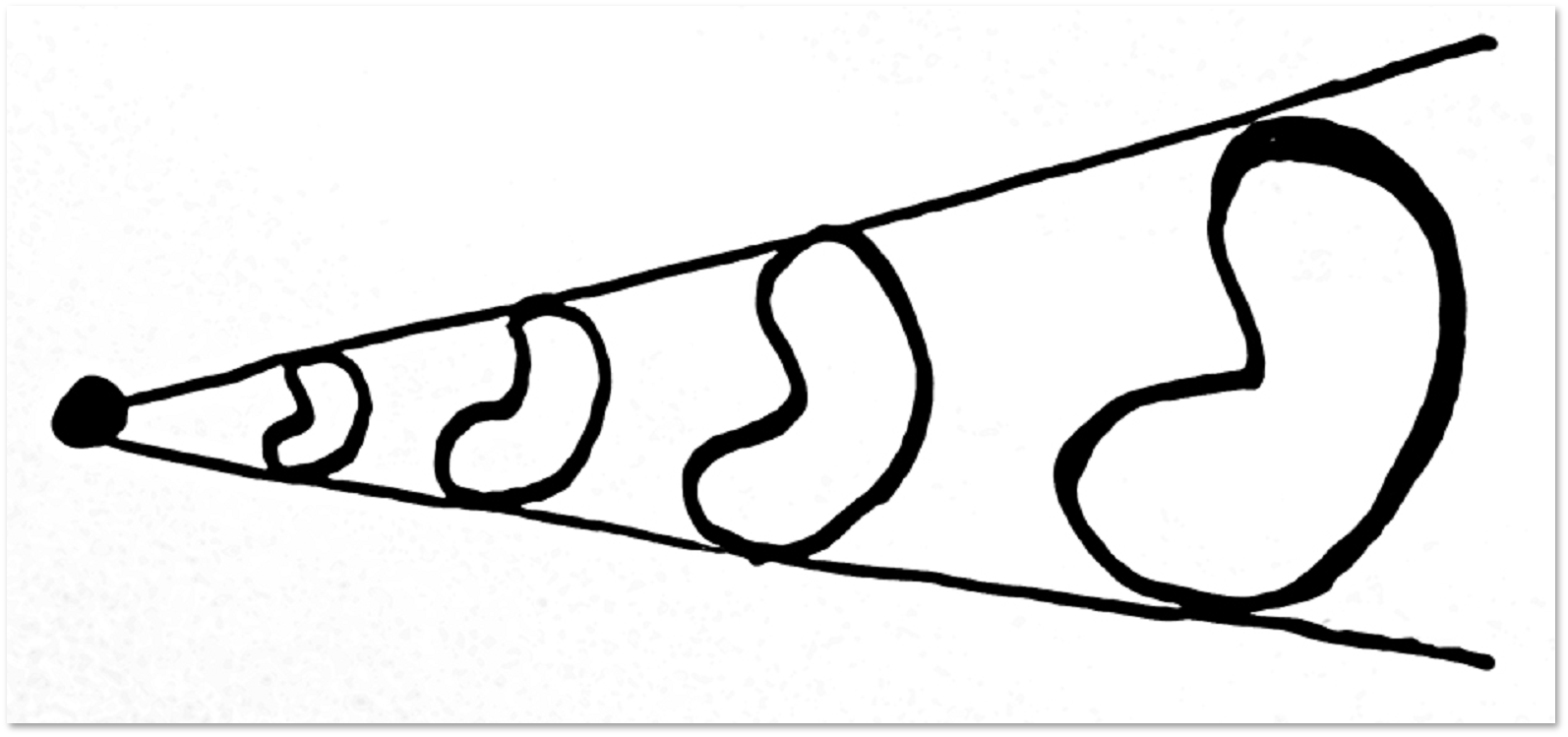

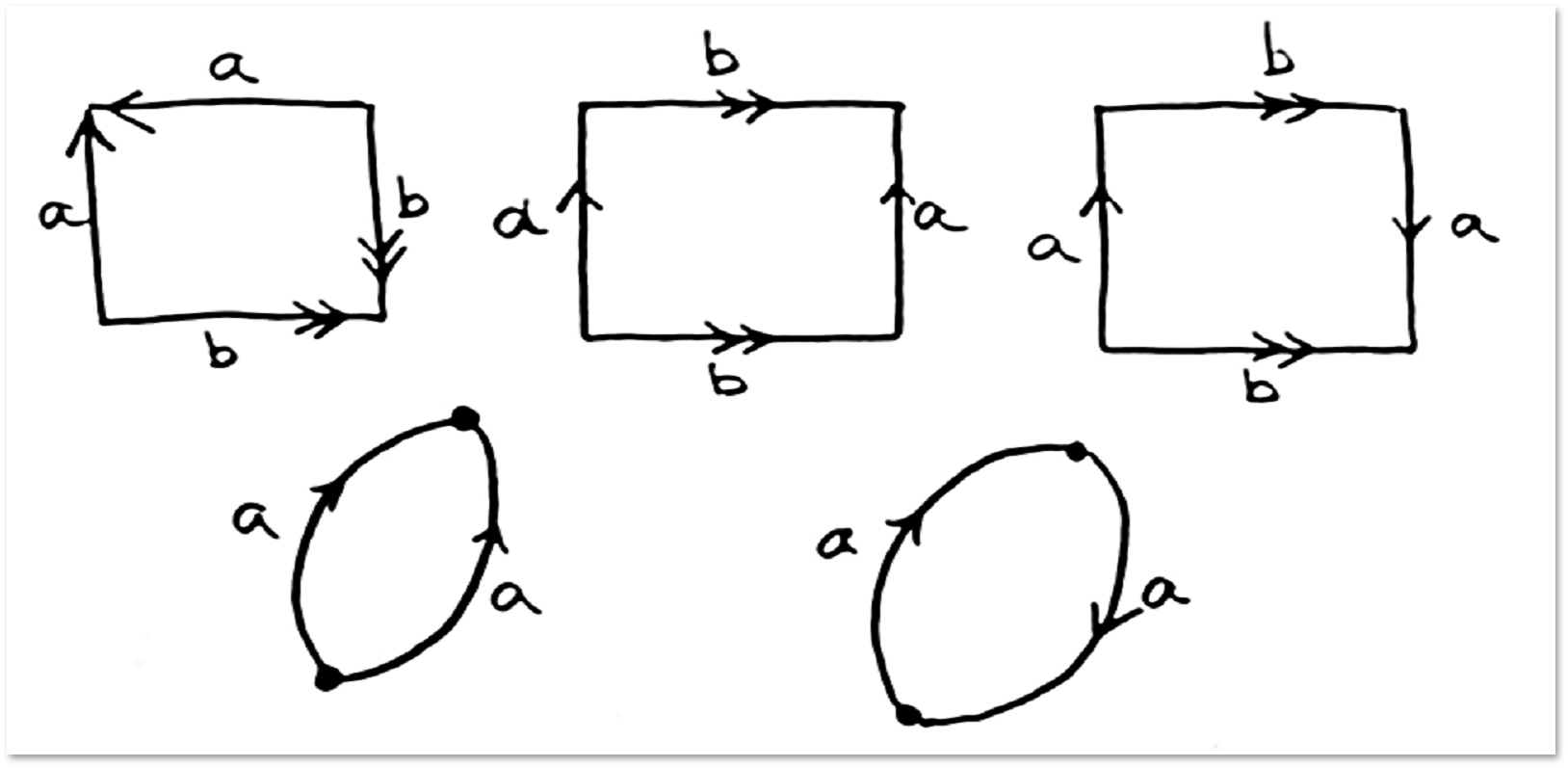

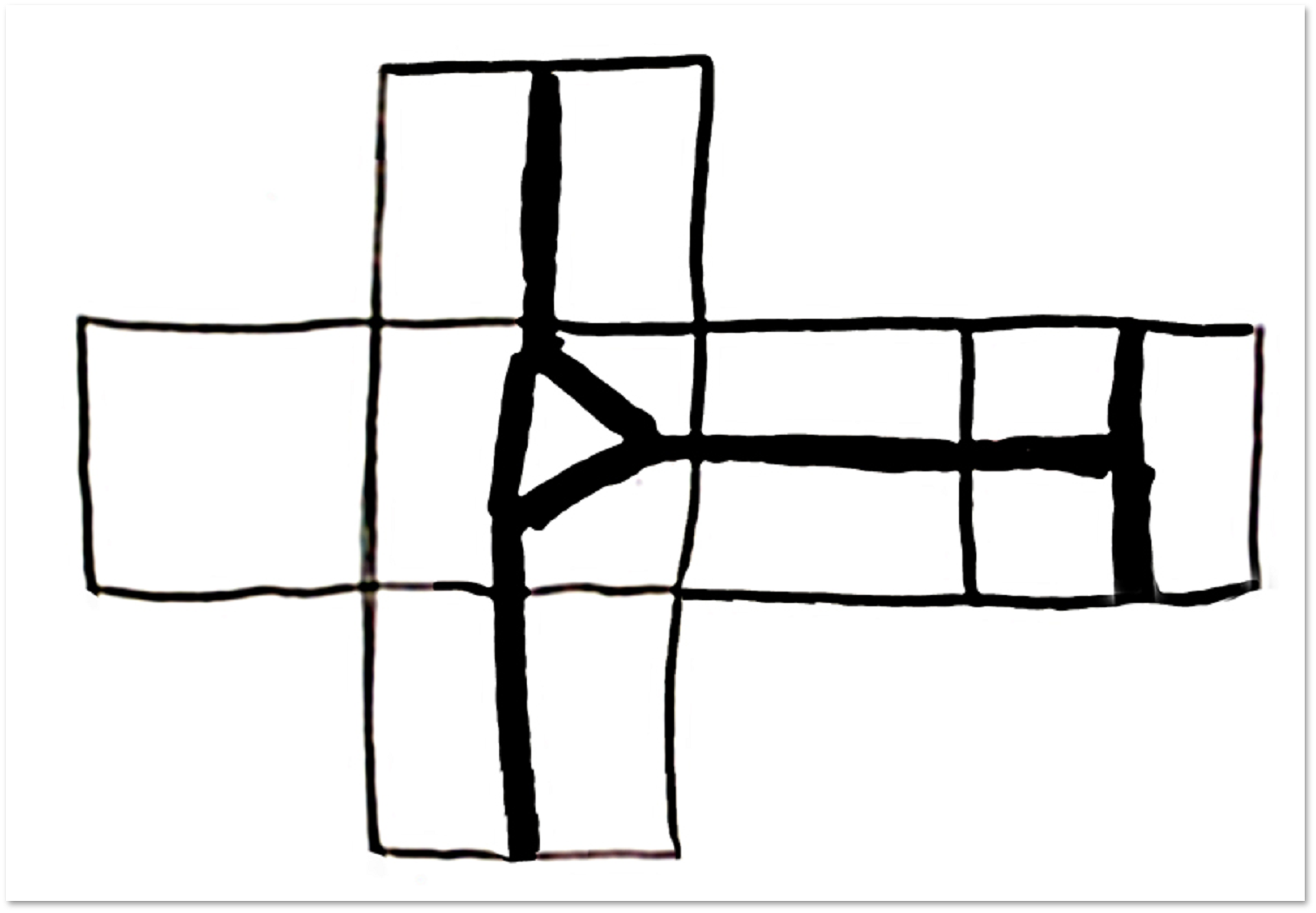

It is easy to figure out that a connected surface can be glued together from one polygon. The picture shows the idea of how this is justified:

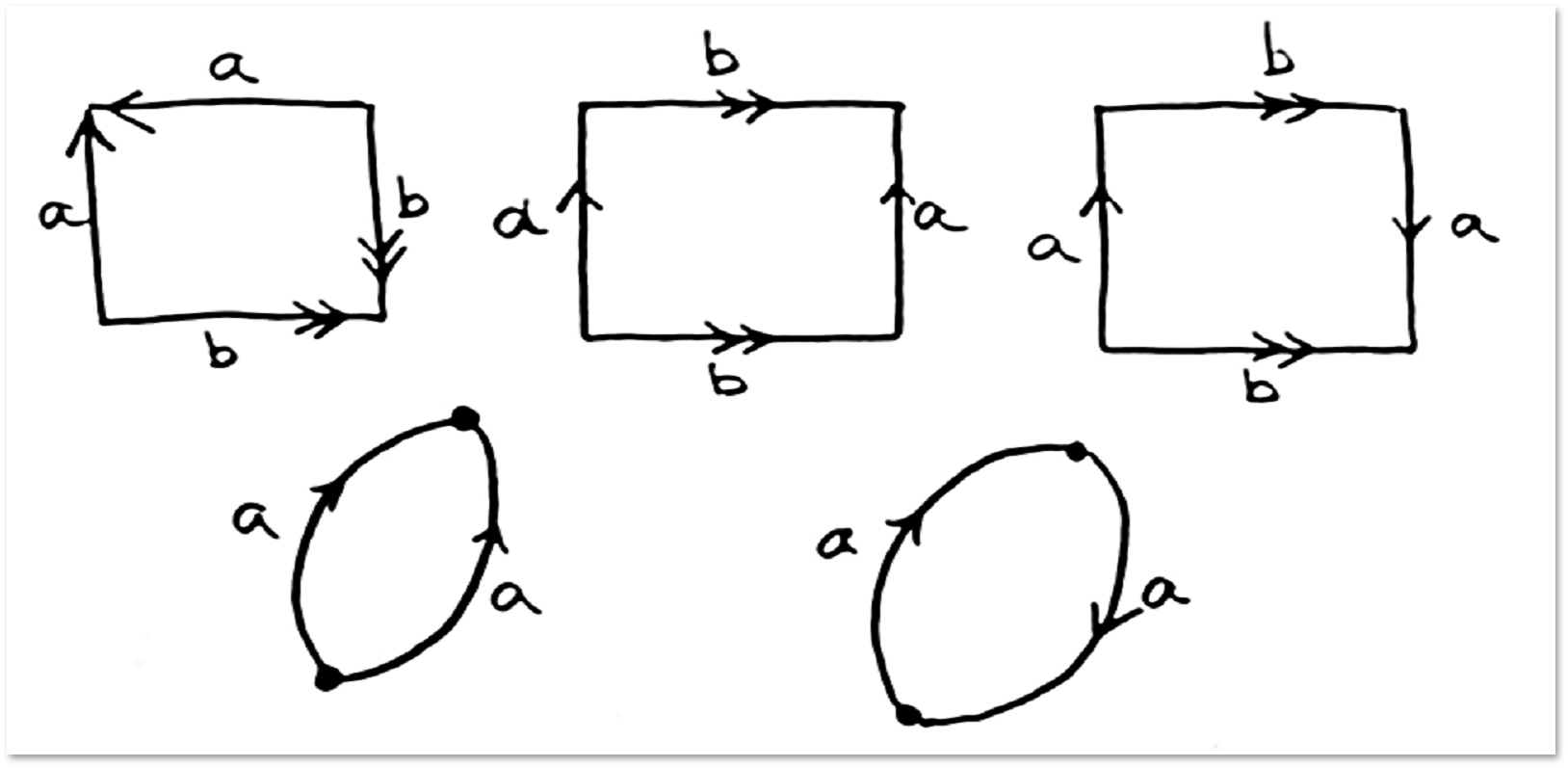

Consider the examples of the simplest gluing:

In the first case, we will have a sphere:

In the second case, we have a torus (the surface of a donut, we met with it before):

In the third case, the so-called Klein bottle is obtained:

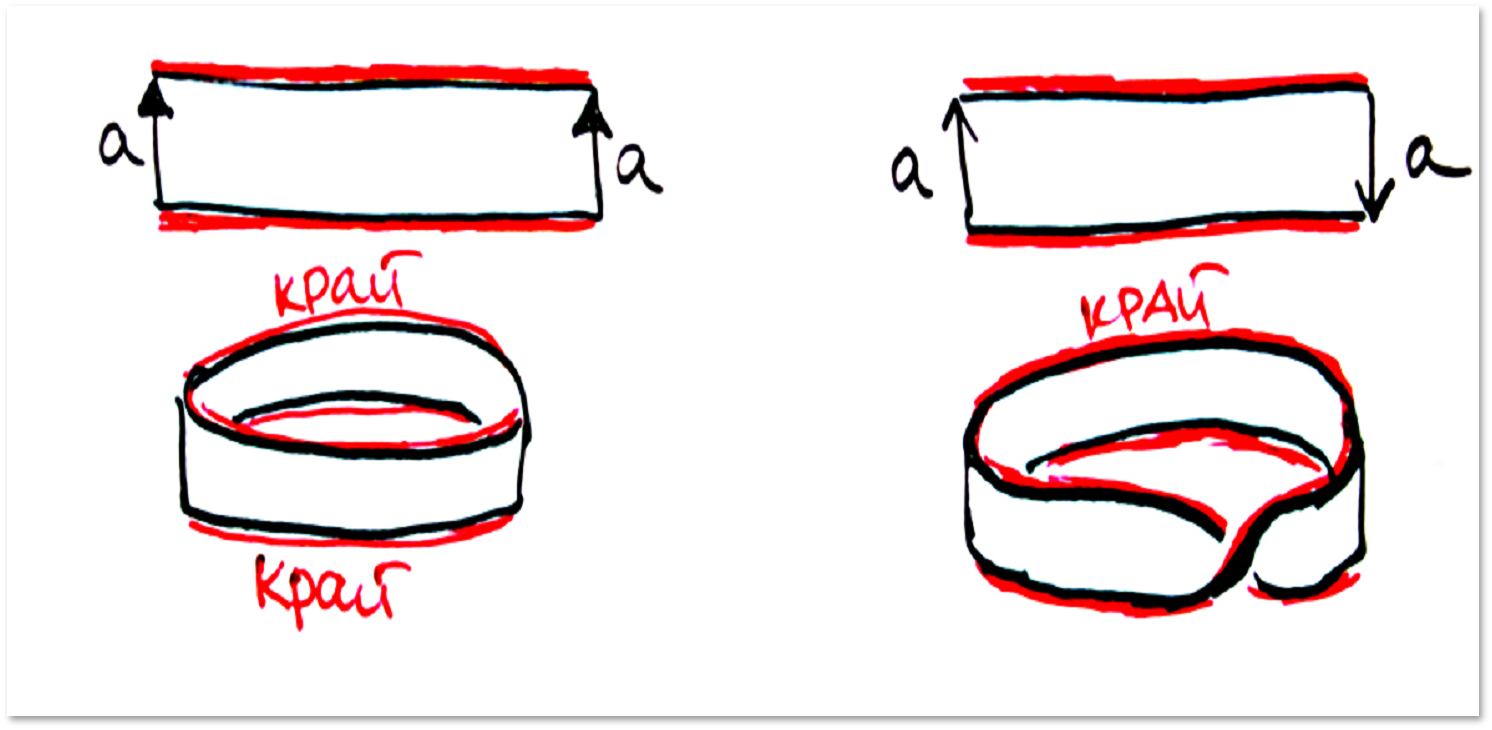

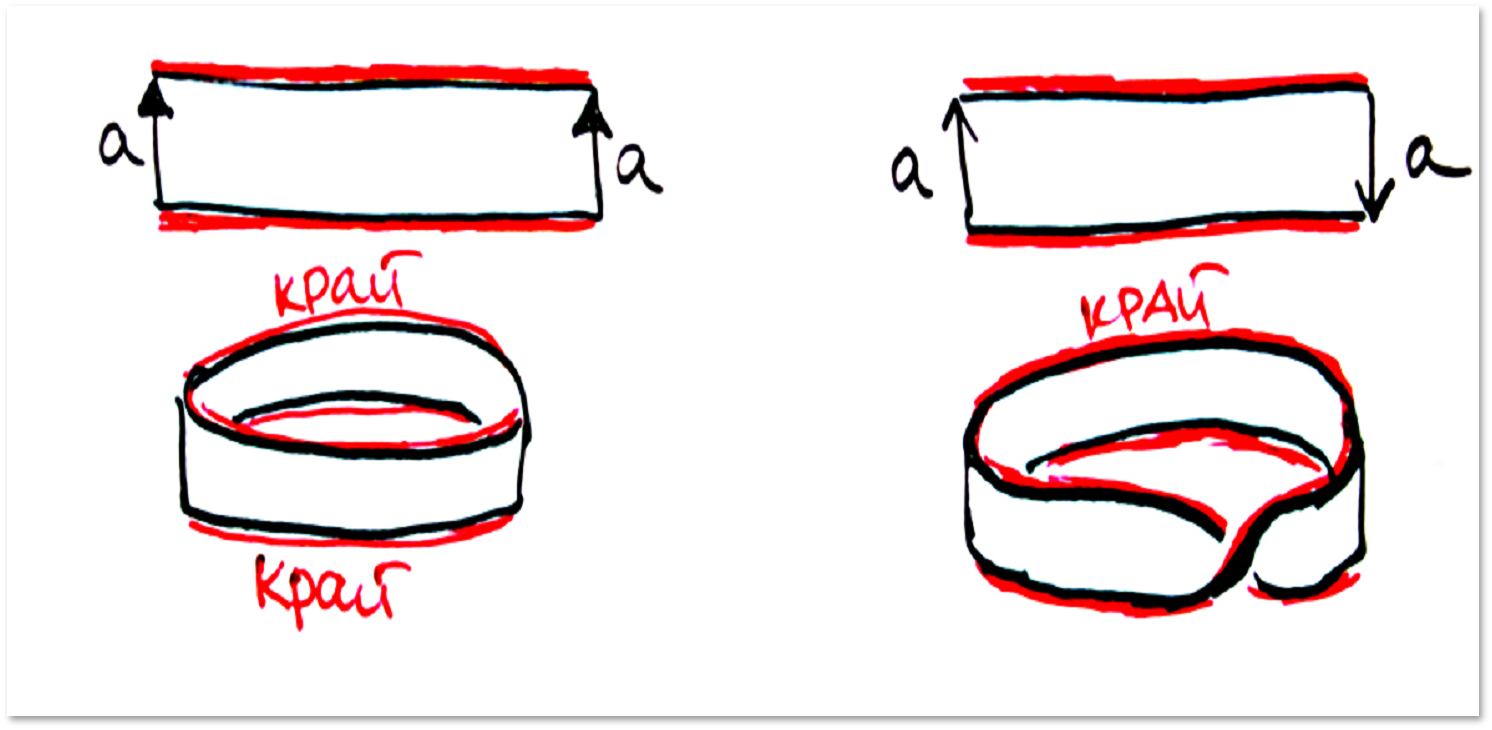

If you do not glue all sides of the polygon, you get a surface with an edge:

It is important to note that after gluing the “scars” from it are purely “cosmetic” in nature. All points of the surface are equivalent: any point has a neighborhood homeomorphic to the disk.

Two surfaces are considered homeomorphic if the gluing patterns of each of them can be cut into gluing patterns of smaller polygons in such a way that the gluing patterns become the same.

Let us analyze this statement by the example of splitting the surface of a cube into parts, from which it is possible to add a development of a tetrahedron:

A more general fact is also true: the surfaces of all convex polyhedra are spheres.

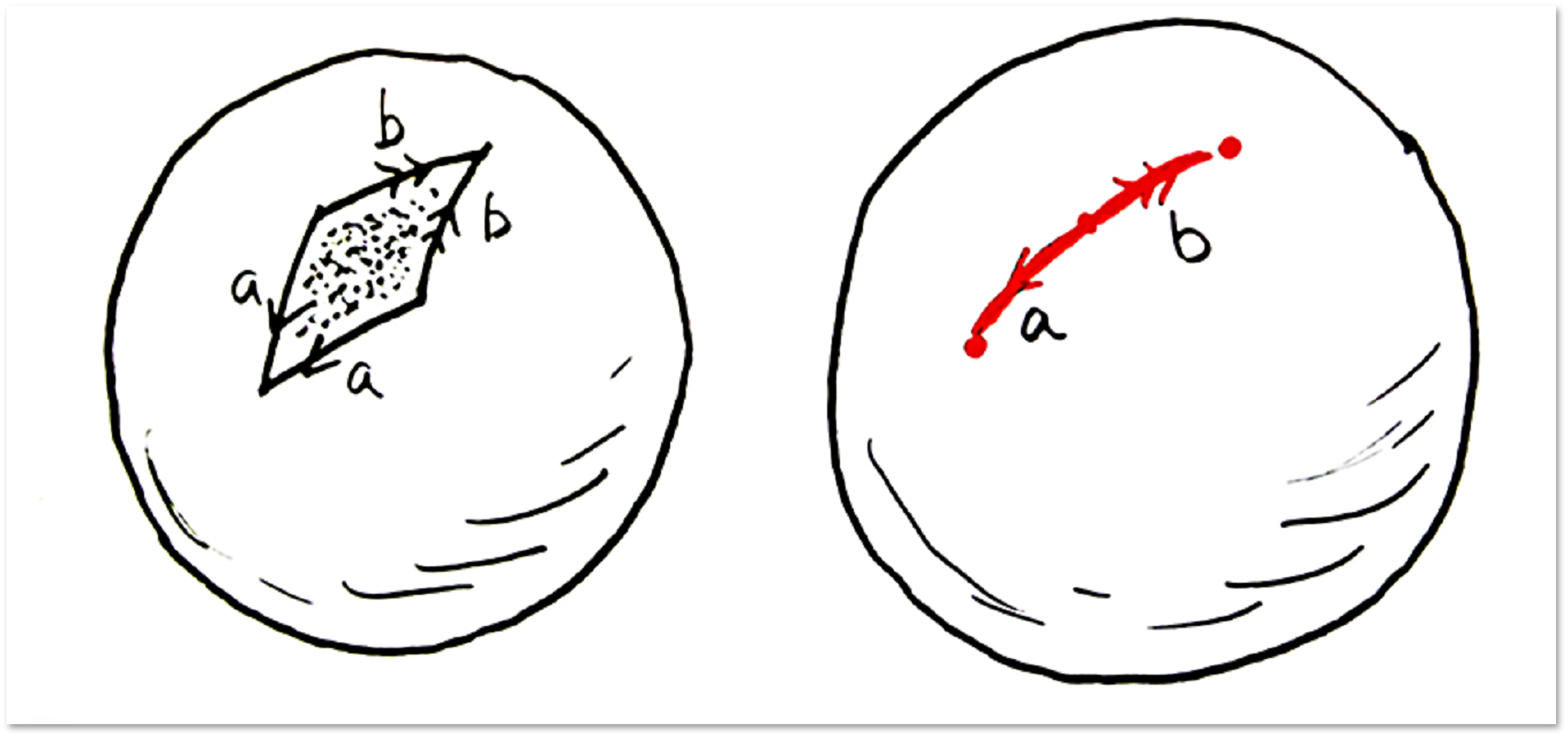

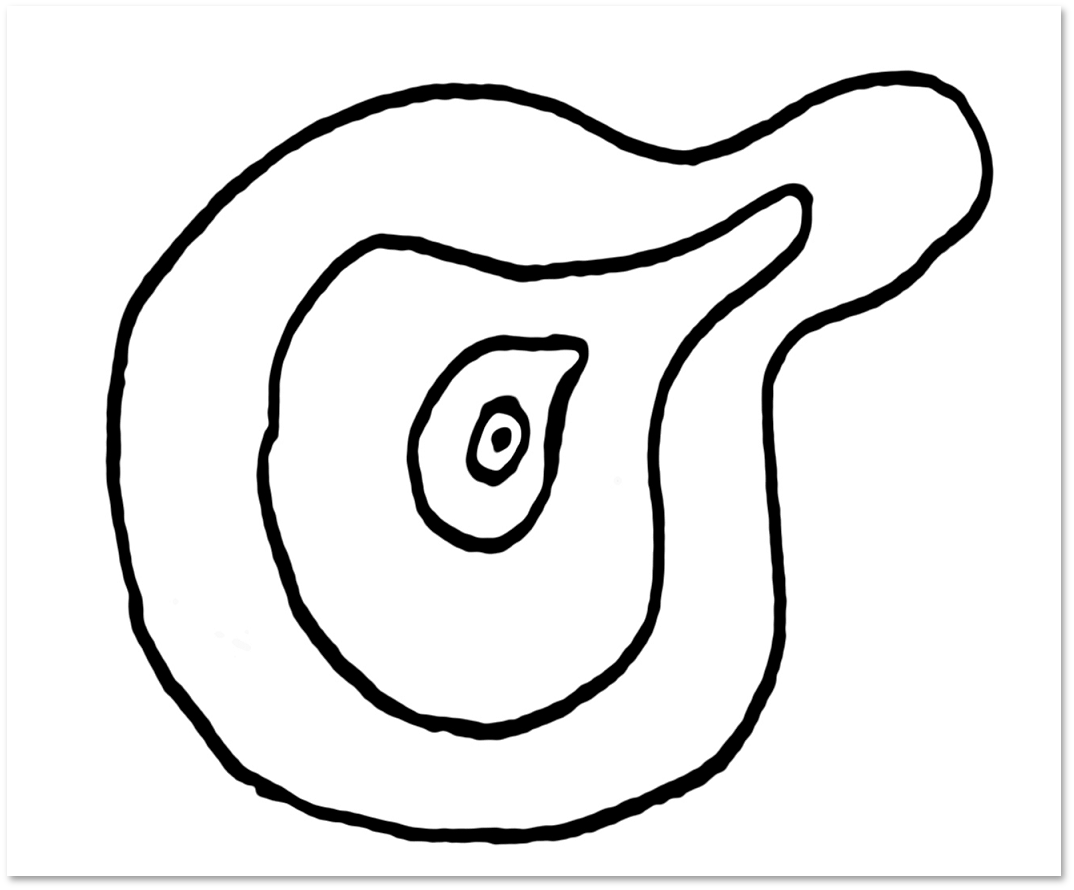

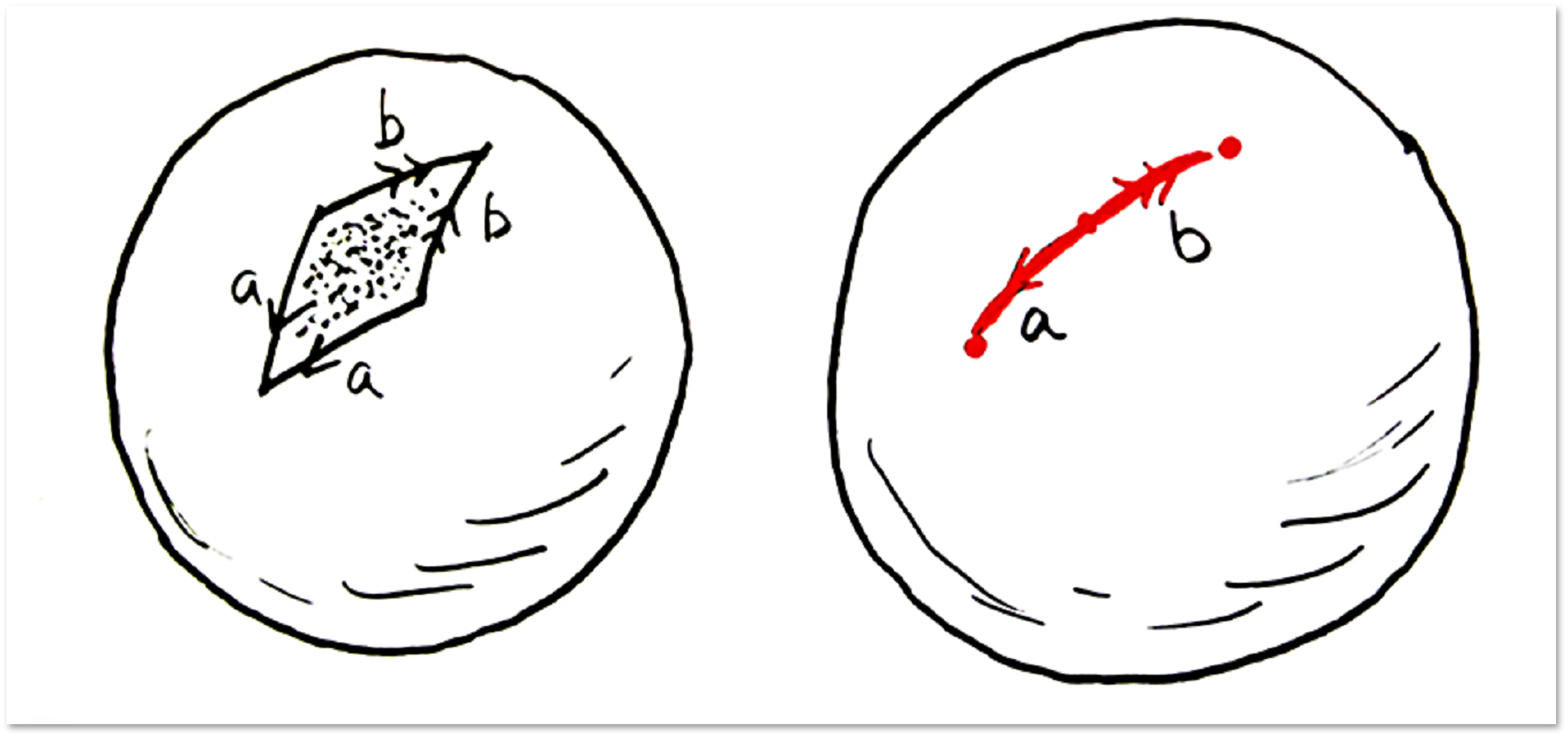

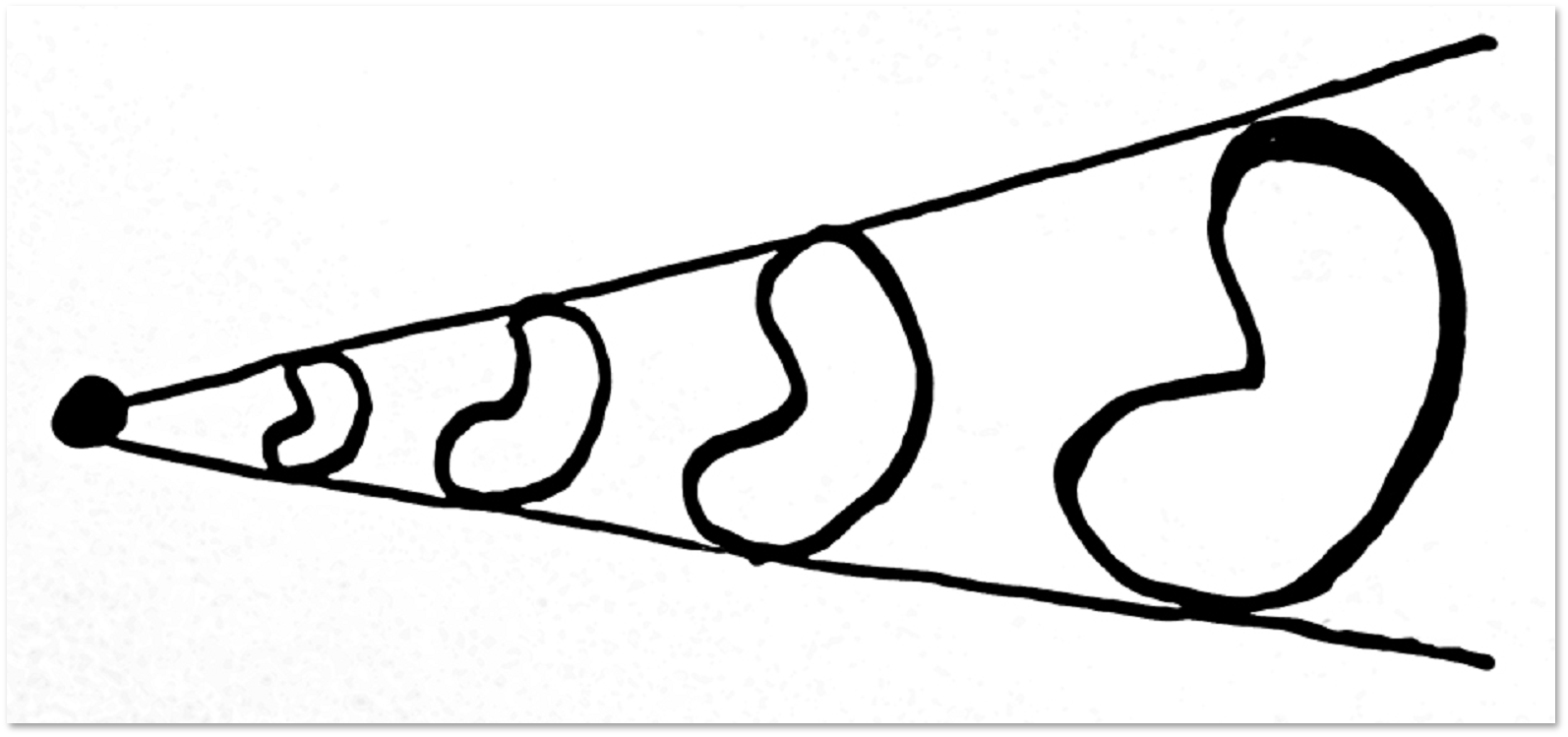

Now let's take a closer look at the concept of a loop. Loop is a closed curve on the surface in question. Two loops are called homotopic if one of them can be deformed into the other without breaks and glueing, remaining on the surface. Below is the simplest case of a loop on a plane or sphere:

Even if a loop on a plane or sphere has self-intersections, you can still tighten it:

On the plane you can tighten any loop:

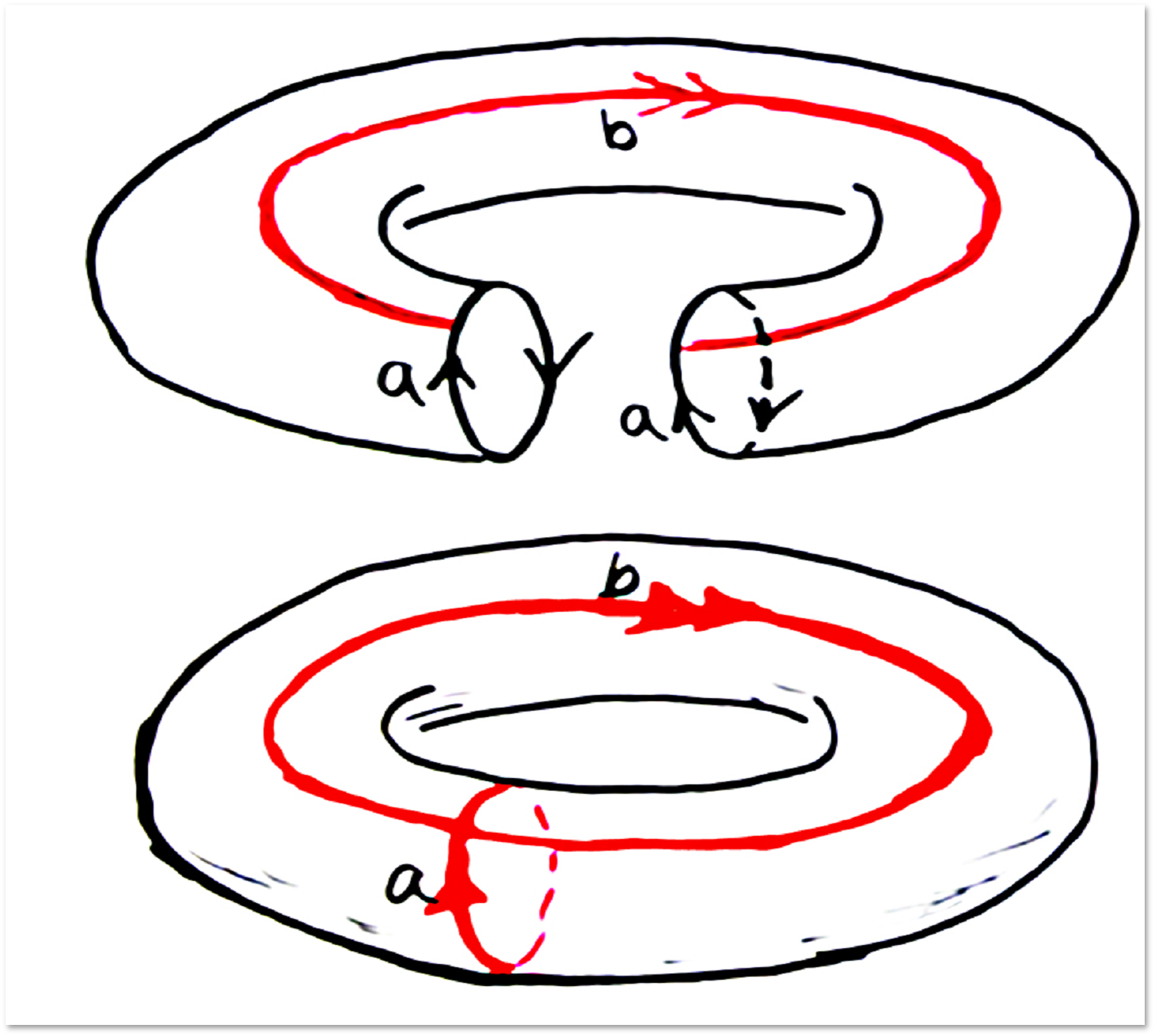

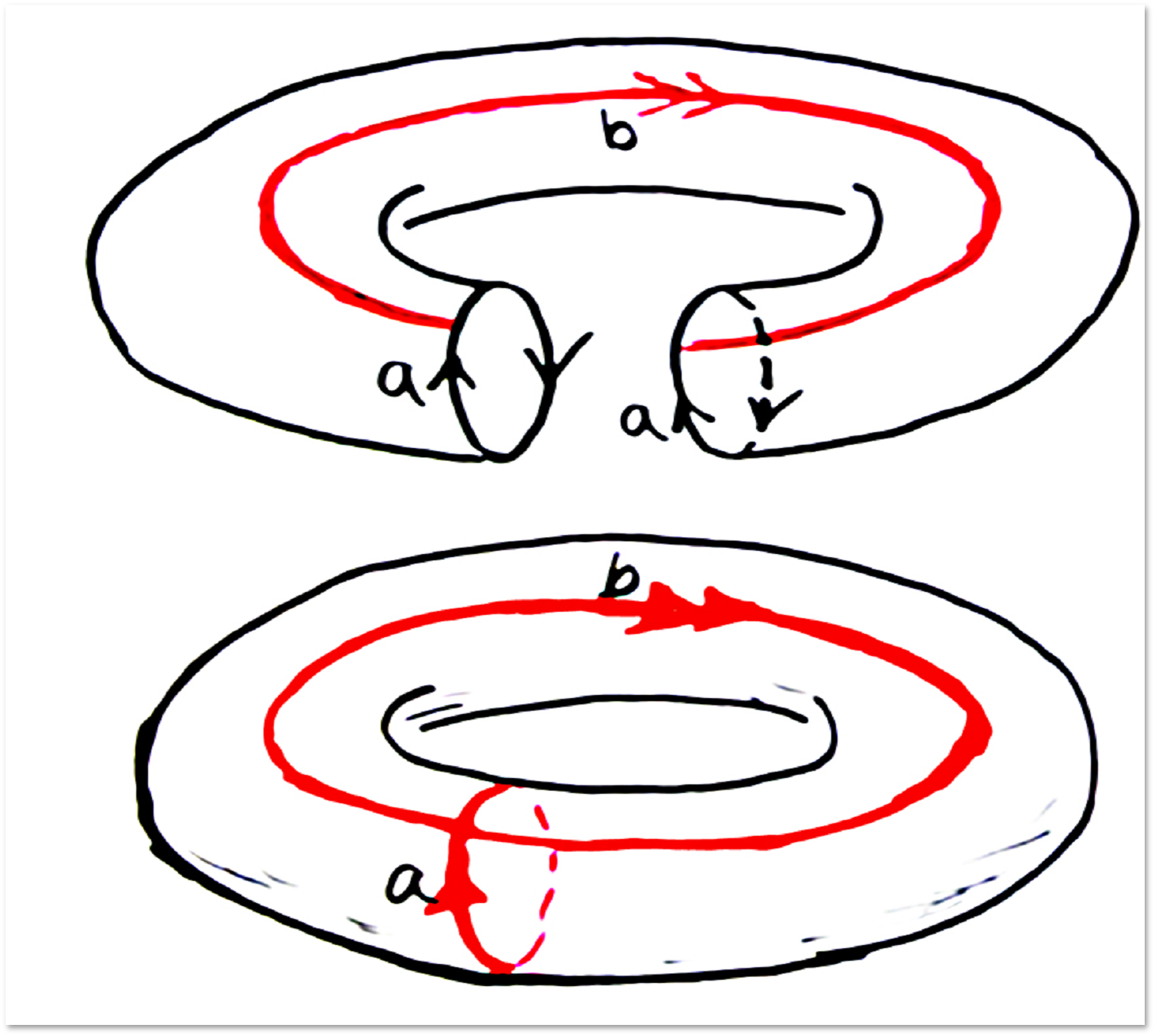

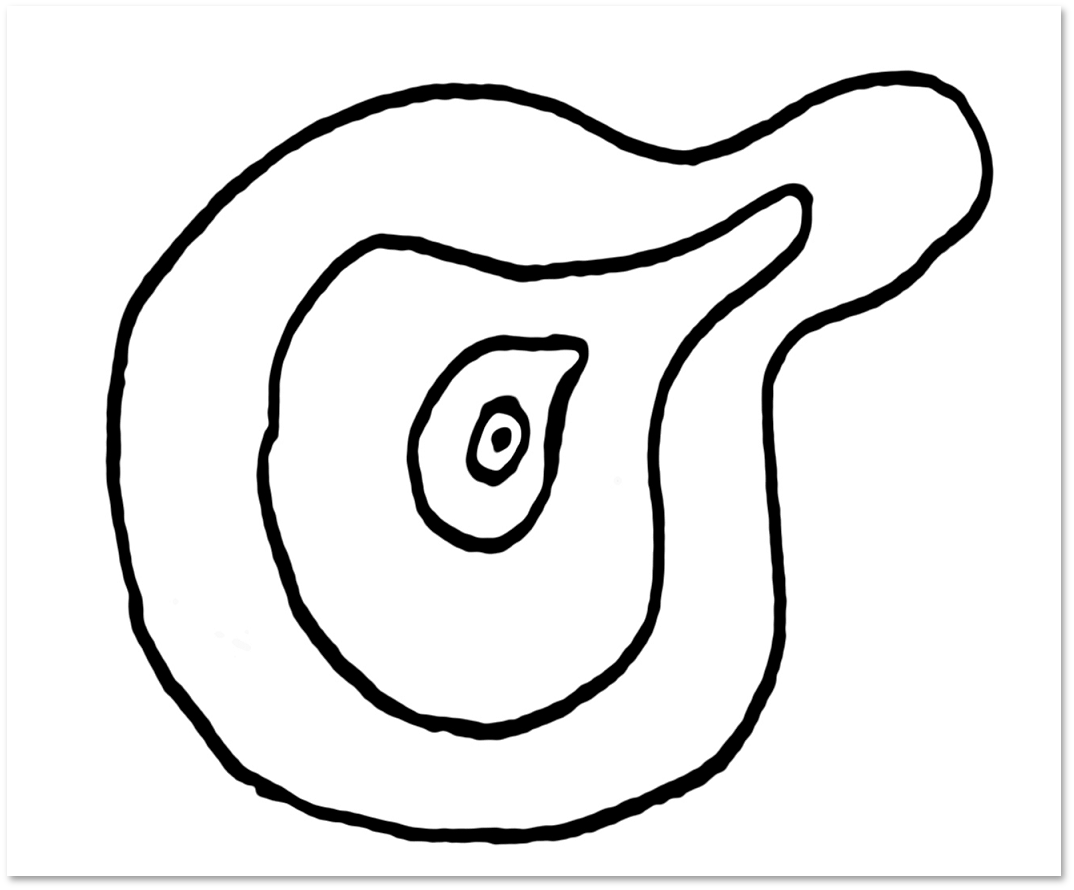

But what loops are on the torus:

To pull such loops impossible. (Unfortunately, the proof goes far enough beyond our story.) Moreover, the loops shown on the torus are not homotopic. We suggest that listeners or readers find another loop on the torus that is not homotopic to these two - this is a very simple question. After that, try to find the fourth loop on the torus, which is not homotopic to these three - it will be somewhat more difficult.

Now that we have become acquainted with all the basic concepts from the formulation of the Poincaré hypothesis, let us try to start the proof of the two-dimensional case (once again we note that this is many times simpler than the three-dimensional case). And help us in this Euler characteristic.

The Euler characteristic of a surface M is the number B − P + Γ. Here Γ is the number of polygons, P is the number of edges after gluing (in the case of the surfaces under consideration, it is half the number of sides of all polygons), B is the number of vertices that is obtained after gluing after gluing.

If two gluing schemes define homeomorphic surfaces, then the numbers B − P + Γ are the same for these schemes, that is, B − P + Γ is an invariant of the surface.

If the surface is already set somehow, then you need to draw some graph on it so that after cutting the surface on it, the surface will break up into pieces homeomorphic to the disks (for example, rings are prohibited). Then we calculate the value of B − P + Γ — this is the Euler characteristic of the surface.

Whether the surfaces with the same Eulerian characteristics will be homeomorphic will be known later. But one can definitely say that if the Euler characteristics of the surfaces are different, then the surfaces are not homeomorphic.

The famous relation B − P + Γ = 2 for convex polygons (Euler's theorem) is a special case of this theorem. In this case we are talking about a specific surface - a sphere. Remark Designation: The Euler characteristic of a surface M will be denoted by χ (M): χ (M) = B - P + Γ

If M is connected, then χ (M) ≤ 2, and moreover, χ (M) = 2 if and only if M is homeomorphic to a sphere.

Having watched the lecture to the end, you will learn how the Poincaré conjecture in dimension 2 does prove, and how Gregory Perelman managed to prove it in dimension 3.

Poincaré managed to prove the hypothesis only in 2003. The proof belongs to our compatriot Grigory Perelman. This lecture sheds light on the objects necessary to formulate a hypothesis, the history of the search for evidence and its main ideas.

')

Lecturers of the Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics of Moscow State University give a lecture to them. n Alexander Zheglov and Ph.D. n Fedor Popelensky.

If you do not go into mathematical details, then the question posed by the Poincare hypothesis can be as follows: how to characterize the (three-dimensional) sphere? In order to properly understand this question, you need to get acquainted with one of the most important concepts in topology — the homeomorphism. Having dealt with it, we will be able to precisely formulate the Poincaré hypothesis.

In order not to get into the mathematical details of a formal definition at all, we will say that two figures are considered homeomorphic if it is possible to establish such a one-to-one correspondence between the points of these figures such that the close points of one figure correspond to the close points of another figure and vice versa. The details we have missed consist precisely in the adequate formalization of the proximity of points.

It is easy to understand that two figures are homeomorphic if one of the other can be obtained by an arbitrary deformation, under which it is forbidden to “spoil” the surfaces (tear, crush areas to a point, make holes, etc.).

For example, to get a hemisphere from a disk, as shown in the picture above, we just need to click on top of its center, holding the outer rim. One can imagine that the surfaces are made of perfect rubber, so that all the figures can contract and stretch as they please. You can not do only two things: tear and glue.

We will have a more accurate (but still not final in terms of severity) idea of homeomorphic figures if we allow another operation: you can make a cut on the figure, twist, tie, untie, etc., but then you must seal the cut as It was.

Let's give one more example. Imagine an apple in which a worm gnawed a knot and a small cave.

From the point of view of topology, the surface of this apple will still remain a sphere, since if we pull it all off in a certain way, we get the surface of the apple in the same way it was before the worm began to eat it.

To consolidate, try to classify the letters of the Latin alphabet to within a homeomorphism (that is, find out which letters are homeomorphic and which are not). The answer depends on the type of letters (on the type of the font or on the typeface), and for the simplest version of the style it is shown in the following figure:

Of the 26 letters we get only 8 classes.

The following picture shows the weight, coffee cup, bagel, dryer and pretzel. From a topological point of view, the surface of the weight, coffee cup, bagel and drying are the same, i.e. homeomorphic. As for the pretzel, it is shown here for comparison with the surface, which in the topology is often called a pretzel (it is depicted in the lower right corner of the picture). As you probably already understand, both the topological pretzel and the edible pretzel are different from the torus.

Formal question

Let M be a closed connected manifold of dimension 3. Let any loop on it be pulled to a point. Then M is homeomorphic to a three-dimensional sphere.

The greatest difficulty for an unprepared person here is the notion of “variety of dimension 3” and properties expressed by the words “closed” and “connected”. Therefore, we will try to deal with all these concepts and properties using the example of dimension 2, in this case much is radically simplified.

Poincare hypothesis for surfaces

Let M be a closed connected surface (a manifold of dimension 2). Let any loop on it be tied to a point. Then the surface M is homeomorphic to a two-dimensional sphere.

First, we define what a surface is. Take a finite set of polygons, divide all their sides (edges) into pairs (i.e. all sides of all polygons should have an even number), in each pair we choose which of the two possible ways we can glue them together. We glue. As a result, a closed surface is taught.

If the resulting surface consists of one piece, and not several separate ones, then they say that the surface is connected. From a formal point of view, this means that after pasting from any vertex of any polygon, one can go along edges to any other vertex.

Here is a simple example: if we assume that in the picture above all the triangles are correct, then after gluing together we should have a regular tetrahedron, the surface of which is also homeomorphic to a sphere.

Formally, it is necessary to require that from any vertex of any polygon after gluing it is possible to pass to any vertex of any polygon (along the edges).

It is easy to figure out that a connected surface can be glued together from one polygon. The picture shows the idea of how this is justified:

Consider the examples of the simplest gluing:

In the first case, we will have a sphere:

In the second case, we have a torus (the surface of a donut, we met with it before):

In the third case, the so-called Klein bottle is obtained:

If you do not glue all sides of the polygon, you get a surface with an edge:

It is important to note that after gluing the “scars” from it are purely “cosmetic” in nature. All points of the surface are equivalent: any point has a neighborhood homeomorphic to the disk.

Two surfaces are considered homeomorphic if the gluing patterns of each of them can be cut into gluing patterns of smaller polygons in such a way that the gluing patterns become the same.

Let us analyze this statement by the example of splitting the surface of a cube into parts, from which it is possible to add a development of a tetrahedron:

A more general fact is also true: the surfaces of all convex polyhedra are spheres.

Now let's take a closer look at the concept of a loop. Loop is a closed curve on the surface in question. Two loops are called homotopic if one of them can be deformed into the other without breaks and glueing, remaining on the surface. Below is the simplest case of a loop on a plane or sphere:

Even if a loop on a plane or sphere has self-intersections, you can still tighten it:

On the plane you can tighten any loop:

But what loops are on the torus:

To pull such loops impossible. (Unfortunately, the proof goes far enough beyond our story.) Moreover, the loops shown on the torus are not homotopic. We suggest that listeners or readers find another loop on the torus that is not homotopic to these two - this is a very simple question. After that, try to find the fourth loop on the torus, which is not homotopic to these three - it will be somewhat more difficult.

Euler characteristic

Now that we have become acquainted with all the basic concepts from the formulation of the Poincaré hypothesis, let us try to start the proof of the two-dimensional case (once again we note that this is many times simpler than the three-dimensional case). And help us in this Euler characteristic.

The Euler characteristic of a surface M is the number B − P + Γ. Here Γ is the number of polygons, P is the number of edges after gluing (in the case of the surfaces under consideration, it is half the number of sides of all polygons), B is the number of vertices that is obtained after gluing after gluing.

If two gluing schemes define homeomorphic surfaces, then the numbers B − P + Γ are the same for these schemes, that is, B − P + Γ is an invariant of the surface.

If the surface is already set somehow, then you need to draw some graph on it so that after cutting the surface on it, the surface will break up into pieces homeomorphic to the disks (for example, rings are prohibited). Then we calculate the value of B − P + Γ — this is the Euler characteristic of the surface.

Whether the surfaces with the same Eulerian characteristics will be homeomorphic will be known later. But one can definitely say that if the Euler characteristics of the surfaces are different, then the surfaces are not homeomorphic.

The famous relation B − P + Γ = 2 for convex polygons (Euler's theorem) is a special case of this theorem. In this case we are talking about a specific surface - a sphere. Remark Designation: The Euler characteristic of a surface M will be denoted by χ (M): χ (M) = B - P + Γ

If M is connected, then χ (M) ≤ 2, and moreover, χ (M) = 2 if and only if M is homeomorphic to a sphere.

Having watched the lecture to the end, you will learn how the Poincaré conjecture in dimension 2 does prove, and how Gregory Perelman managed to prove it in dimension 3.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/211851/

All Articles