The IceCube detector registered neutrinos from outside the solar system.

Scientists first received reliable traces of neutrinos from outside the solar system. Of course, no one doubted their existence, but now they managed to register them for the first time and prove that the source is in deep space. The neutrino detector IceCube at the South Pole helped in this.

IceCube found 28 neutrinos with abnormally high energy. “This is a huge result. He can mark the beginning of neutrino astronomy - Darren Grant, assistant professor of physics at the University of Alberta and one of the leaders of the IceCube Collaboration project, which brings together more than 250 physicists and engineers from a dozen countries, does not hide his joy .

Neutrinos from outside the solar system have higher energy. They were formed as a result of various cosmic phenomena, such as gamma-ray bursts, the formation of black holes and galactic nuclei far in the Universe. The study of these neutrinos allows you to look beyond, limited by the resolution of optical and radio telescopes.

')

Until now, scientists have studied only low-energy neutrinos that were born in the upper layers of the earth’s atmosphere, as well as particles from the nearby supernova 1987A. But 28 new neutrinos have much more energy: from 30 to 1200 TeV! For comparison, after the upgrade of the Large Hadron Collider in 2015, with an increase in its power, it will be able to push particles with the energy of “only” 14 tera-electronvolts.

Neutrino with a record energy of 1.2 PeV was registered on January 3, 2012 and received the name Ernie from physicists

These neutrinos obviously came from afar, and scientists still cannot say where exactly they are from, because 28 neutrinos do not have clustering in time or space. “I’m sure that in 20 years we will look back and say: yes, this was the beginning of neutrino astronomy,” said John Learned in a commentary for the journal Science.

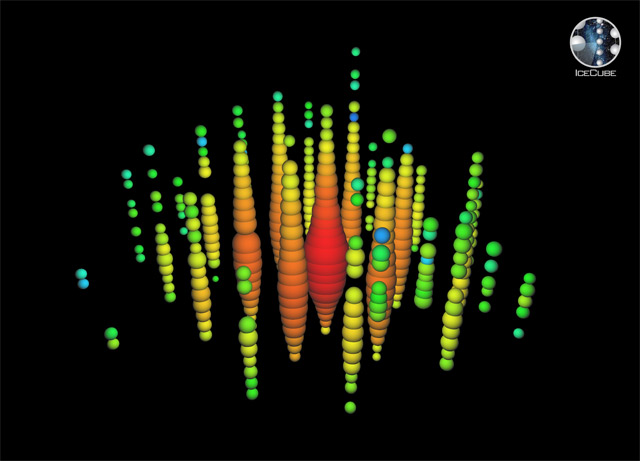

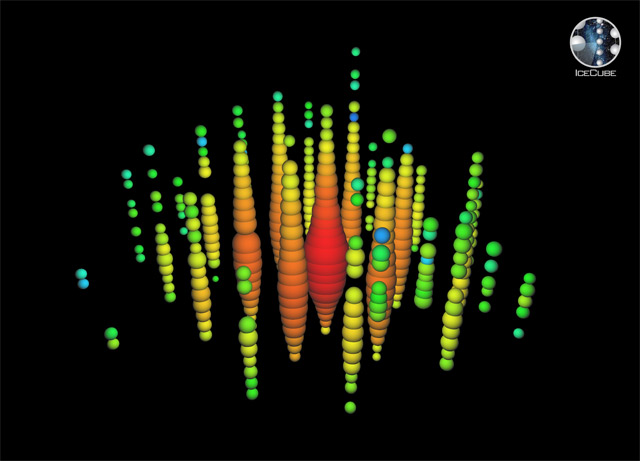

The IceCube neutrino observatory (“Ice Cube”) reached its full capacity in December 2010, although it began to work earlier in a limited mode. The design consists of 5160 optical detectors neatly frozen in ice at a depth of from 1,450 to 2,450 meters (tunnels in the ice were laid with hot water). The detectors are assembled in 86 km strands of 60 pieces each. The design is shown schematically in the illustration.

It turns out that a huge block of ice is used as a detector, which is surrounded on all sides by sensors frozen in there. Here are the separate optical sensors. Sensors register Cherenkov radiation of high-energy muons moving out of the ground. Such muons can be produced only by the interaction of muon neutrinos that have passed through the earth with electrons and ice nucleons. Thousands of kilometers of terrestrial matter serve as a filter, cutting off the "extra" particles. That is, the IceCube at the South Pole detects neutrinos coming from the northern hemisphere of the sky.

Ice "cube" (more precisely, a regular hexagonal prism) is the world's largest neutrino detector. Perhaps he will help obtain the first evidence of the existence of multiple dimensions in the Universe, confirming string theory , on the basis of which the Unified Theory, which is the Grail of modern physics, was formulated.

String theory predicts the existence of sterile neutrinos that come to us from other dimensions with a speed supposedly (for an observer) exceeding the light barrier (as well as the speed of propagation of gravity for us, observers, also supposedly exceeds the light barrier). Actually, it is these sterile neutrinos, among others, that are looking for the IceCube.

The IceCube project started in 2002, and the installation of the detectors began in 2005. By December 2010, the work was completed, in 2011 the system was launched at full capacity - and now, after two and a half years, the first encouraging results were finally obtained. Now we need to continue collecting data, and in a few years it will be possible to determine the source (s) of these neutrinos: as new neutrinos are detected, the picture will gradually appear, as in the photo with a long exposure.

The scientific work describing the first high-energy neutrinos was published in the journal Science on November 22, 2013.

IceCube found 28 neutrinos with abnormally high energy. “This is a huge result. He can mark the beginning of neutrino astronomy - Darren Grant, assistant professor of physics at the University of Alberta and one of the leaders of the IceCube Collaboration project, which brings together more than 250 physicists and engineers from a dozen countries, does not hide his joy .

Neutrinos from outside the solar system have higher energy. They were formed as a result of various cosmic phenomena, such as gamma-ray bursts, the formation of black holes and galactic nuclei far in the Universe. The study of these neutrinos allows you to look beyond, limited by the resolution of optical and radio telescopes.

')

Until now, scientists have studied only low-energy neutrinos that were born in the upper layers of the earth’s atmosphere, as well as particles from the nearby supernova 1987A. But 28 new neutrinos have much more energy: from 30 to 1200 TeV! For comparison, after the upgrade of the Large Hadron Collider in 2015, with an increase in its power, it will be able to push particles with the energy of “only” 14 tera-electronvolts.

Neutrino with a record energy of 1.2 PeV was registered on January 3, 2012 and received the name Ernie from physicists

These neutrinos obviously came from afar, and scientists still cannot say where exactly they are from, because 28 neutrinos do not have clustering in time or space. “I’m sure that in 20 years we will look back and say: yes, this was the beginning of neutrino astronomy,” said John Learned in a commentary for the journal Science.

The IceCube neutrino observatory (“Ice Cube”) reached its full capacity in December 2010, although it began to work earlier in a limited mode. The design consists of 5160 optical detectors neatly frozen in ice at a depth of from 1,450 to 2,450 meters (tunnels in the ice were laid with hot water). The detectors are assembled in 86 km strands of 60 pieces each. The design is shown schematically in the illustration.

It turns out that a huge block of ice is used as a detector, which is surrounded on all sides by sensors frozen in there. Here are the separate optical sensors. Sensors register Cherenkov radiation of high-energy muons moving out of the ground. Such muons can be produced only by the interaction of muon neutrinos that have passed through the earth with electrons and ice nucleons. Thousands of kilometers of terrestrial matter serve as a filter, cutting off the "extra" particles. That is, the IceCube at the South Pole detects neutrinos coming from the northern hemisphere of the sky.

Ice "cube" (more precisely, a regular hexagonal prism) is the world's largest neutrino detector. Perhaps he will help obtain the first evidence of the existence of multiple dimensions in the Universe, confirming string theory , on the basis of which the Unified Theory, which is the Grail of modern physics, was formulated.

String theory predicts the existence of sterile neutrinos that come to us from other dimensions with a speed supposedly (for an observer) exceeding the light barrier (as well as the speed of propagation of gravity for us, observers, also supposedly exceeds the light barrier). Actually, it is these sterile neutrinos, among others, that are looking for the IceCube.

The IceCube project started in 2002, and the installation of the detectors began in 2005. By December 2010, the work was completed, in 2011 the system was launched at full capacity - and now, after two and a half years, the first encouraging results were finally obtained. Now we need to continue collecting data, and in a few years it will be possible to determine the source (s) of these neutrinos: as new neutrinos are detected, the picture will gradually appear, as in the photo with a long exposure.

The scientific work describing the first high-energy neutrinos was published in the journal Science on November 22, 2013.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/203634/

All Articles