Construction of conic sections

The other day, debugging a fragment of a program related to geometric calculations, I noticed that one of the variables has the same value regardless of the values of the input parameters. Naturally, first of all I suspected an error and spent some time searching for it, but after a little thinking, I realized that this was not an error, but one of the known properties of conic sections that I often forget about. After that, I had already spent much more time drawing beautiful geometric constructions, and in the end I decided that it was worth sharing the pictures with someone. So this Friday article appeared.

Let me remind you (and I will inform those who did not teach higher mathematics) that such curves as ellipse, parabola and hyperbola are called conic sections (there are still degenerate cases — we will not dwell on them now). In general, conic sections are a very remarkable object, they are found in many areas. We can recall, for example, parabolic antennas or the orbits of celestial bodies.

Each conic section is a section of a cone (albeit, CEP?), That is, a line formed at the intersection of the cone and the plane. Well, the appearance depends on the relative position of the plane and forming a cone. It is also easy to prove that all such lines are graphs of second-order equations.

Does anyone need proof?

The cone is described by a canonical second order equation

The securing plane can be turned into the z = 0 plane by making a linear change of coordinates. It is clear that after a linear change of coordinates the degree of the equation does not increase and, substituting the value z = 0 into this equation, we obtain the desired second-order equation.

The securing plane can be turned into the z = 0 plane by making a linear change of coordinates. It is clear that after a linear change of coordinates the degree of the equation does not increase and, substituting the value z = 0 into this equation, we obtain the desired second-order equation.

All who taught higher mathematics probably spent a certain amount of time learning the classification of lines and surfaces of the second order (the words to God are not too many, especially if you do not take into account imaginary figures).

But for the classical definitions of ellipse, parabola and hyperbola, they use another property, namely (I quote Wikipedia):

An ellipse is a locus of points on a Euclidean plane for which the sum of the distances to two given points (called foci) is constant and greater than the distance between these points.

Hyperbola is the locus of points of the Euclidean plane for which the absolute value of the difference of distances to two selected points (called foci) is constant.

')

Parabola is the locus of the points of the Euclidean plane, equidistant from this line and this point.

The proof of these properties is straightforward. It is necessary to take the corresponding second-order equation, carefully write down the formulas for distances and perform algebraic transformations. The calculations are rather cumbersome, so here I will give only the simplest case - a parabola.

Want formulas?

Let the parabola be given by the equation y = a * x * x, where a is a constant. Calculate the distance from any point of the parabola to the point with coordinates (0, 1 / (4a)):

Here the second transformation was carried out using the parabola equation, and the rest is simply the rearrangement of elements and the opening of the brackets. It turned out that the distance from the point of the parabola to the point (0, 1 / (4a)) is equal to the distance from the same point of the parabola to the straight line y = -1 / (4a), as required.

Here the second transformation was carried out using the parabola equation, and the rest is simply the rearrangement of elements and the opening of the brackets. It turned out that the distance from the point of the parabola to the point (0, 1 / (4a)) is equal to the distance from the same point of the parabola to the straight line y = -1 / (4a), as required.

The term “locus of points” immediately resembles a school desk and constructions with a compass and a ruler. In general, this was my favorite part of geometry, although it was often easier to act algebraically. Of course, it is impossible to fully construct the conic sections using a compass and a ruler, but you can construct any number of points lying on these curves. The easiest way to do this is to use the properties mentioned. Consider this construction for an ellipse.

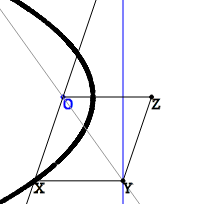

Let O and Q be the foci of an ellipse and 2a be the given sum of distances. Take any straight line passing through the focus O and consider the point X - the intersection of the line and the ellipse. Putting on the same straight line segment OY equal to 2a, we get the triangle QXY. By the property of an ellipse, QX + OX is 2a, which means QX = XY and the indicated triangle is isosceles. This makes it easy to restore the point X by constructing the median perpendicular to QY.

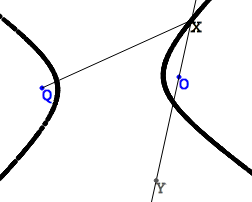

For hyperbola, the construction is similar, only the point Y should be put aside in the other direction. It turns out that OY is the difference of the XY and OX segments, and the triangle QXY is still isosceles. Since the construction algorithm is the same, what exactly happens is an ellipse or hyperbola depends on the distance between the foci or the length of the segment specifying the sum (difference).

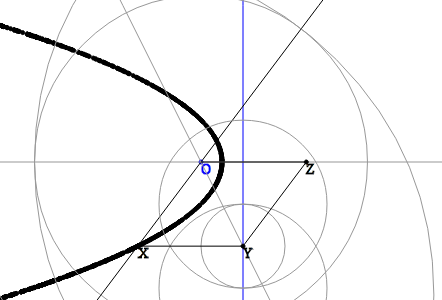

The parabola is a little more complicated. Let O be the focus of a parabola and be given a director. Instead of an isosceles rectangle, here we need to consider the OXYZ Parallelogram, where the straight lines XY and OZ are perpendicular to the director. By the parabola property, XY = XO, therefore, this parallelogram is a rhombus. Having the line OX restore the rhombus and find the point X is already easy - just hold the bisector of the angle XOZ - get the point Y, as the intersection of the bisector and directrix, and then restore the perpendicular from this point to the intersection with the defining line.

The parabola drawing process is captured in the following video:

Well, everyone can independently see the sequence of constructions, move the setting points and watch the fascinating movement of auxiliary circles here . Do not forget to move the points signed as “Drag me”.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/202112/

All Articles