Imagination like that of esmeralda

(From the translator: this text appeared in the blog of one of the developers of the Go language on New Year's Eve 2012. The text did not lose its relevance in the past two years; moreover, instead of Go, any other non-mainstream language could well be in the text. Actually, that’s text and narrates.)

One of my friend's actress — let's call her Esmeralda — once said, “I always knew that I would become an actress. I can’t even imagine that I was somebody else! ”Someone retorted:“ What kind of actress is you then? ”

I remembered this conversation after reading a review about the Go language: “I can't even imagine how to program in a language without generics!” I just wanted to parry: “Which programmer are you from?”

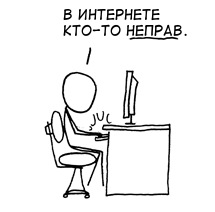

This note is not about generics - I have nothing against them: maybe one day they will appear in Go, and maybe not. This note is about imagination , or at least what programmers usually think of as imagination: claims. A friend of mine said that the most common way to spend free time today is to shake the air of the Network with its complaints. For complainers, this is soothing relief; but the addressees of the inexhaustible flow of complaints are very depressing. They complained so much about me that now I myself have become in need of relaxation. What am I doing for this? right, I write a perturbed post to my blog.

')

Not so long ago, the programmer was considered the one who wrote the program. Now the programmer is least willing to spend time on programming. A programmer today is one who sits and is indignant, if for his task there is no ready-made solution that fits into one line of code. (From the point of view of a language developer, the success criterion for a language is so that any program can be reduced to a single line of code. The example of APL did not teach anyone anything.)

A broader definition of a modern programmer: this is the one who tries to solve any task in the same way, and if he fails, he is outraged by the imperfection of his tools.

When a programmer is forced to program, or even at least turn on his head at the time of writing the code, then he shares his indignation with the subscribers of his blog, twitter, and with his neighbors in the office. The walls of the text, imbued with sincere indignation at the fact that to solve the problem X in a certain language is required to print an extra ten characters. How do they not notice the absurdity in the fact that they spend thousands of extra characters on their indignant posts? If the same time they spent on solving problem X, it would have been solved ten times already. But unless they will begin to spend the precious time for programming ?!

Two years ago, Go came out, this year - Dart. These languages have different groups of developers, and they set themselves different goals: there’s hardly anything in common between Go and Dart, except that both are released by Google. But I was struck by how many first reviews about Dart almost literally repeated the first reviews that we received after the release of Go - only with the replacement of the name “Go” by “Dart”. It is not necessary to try to write something on Go or Dart before publishing your claims to a new language; on the contrary, it is important not to try to program - then your review will be "unbiased"!

In both cases, there were a lot of loud and impressively written reviews, but they all do not express anything about the language about which they were written. This is the usual reaction of a modern programmer to something new and unfamiliar. Void quibbles that serve only to satisfy the author’s desire to complain about anything. For this, you don’t have to worry too much: the same nagging approaches an infinite number of languages (“I can’t even imagine how to program in a language without XXX!”) And, unlike the code, quibbles are not checked by the compiler for no errors .

Some time after the release of Go, the tone of the reviews changed a bit: some people still tried to program it. Now the problem was that they — like that commentator who started this post about the story — lacked imagination. Go is a language for programming on Go, not a new syntax for Java, for Haskell, or for other existing languages. To write a good program on Go, you need to think differently than when programming in Java. Instead, modern programmers shorten the path: take the finished code, and rewrite it on Go. The code on Go at the same time, indeed, sometimes goes awkward. But it's not about Go: if the same program were written on Go from the very beginning , using other approaches - more natural for Go and less applicable in the same Java - then the code would be more vivid and vibrant. But to learn to think differently , you need to spend time and energy - more than Go critics can afford. How astute about Go would you expect from a person with ten years of Java experience and ten minutes of Go experience? Nevertheless, such reviews are published and enthusiastically discussed by programmers. No wonder: what can fascinate modern programmers more than online complaints?

Of course, I exaggerate. For two years, enough programmers took the time to learn how to use Go correctly , and many of them were satisfied with the results they achieved. A growing community of Go programmers has created a bunch of great programs, and the hope that I still have real programmers in the world has returned to me. Programmers who are clear: to learn how to properly use any programming language, you need time, you need imagination, and you need programming practice in that language; all these costs will pay off with the results achieved.

But the vacuous criticism of Go on the Internet is still abundant. Therefore, I want to start the new 2012 with such a statement: “In any complaint, I will see first of all a testimony about the nature of the complainant, and not about the subject of the complaint. To earn credibility among programmers, we need not complaints, but experience and insight, and for this we need imagination. A little programming practice doesn't hurt either. ”

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/197398/

All Articles