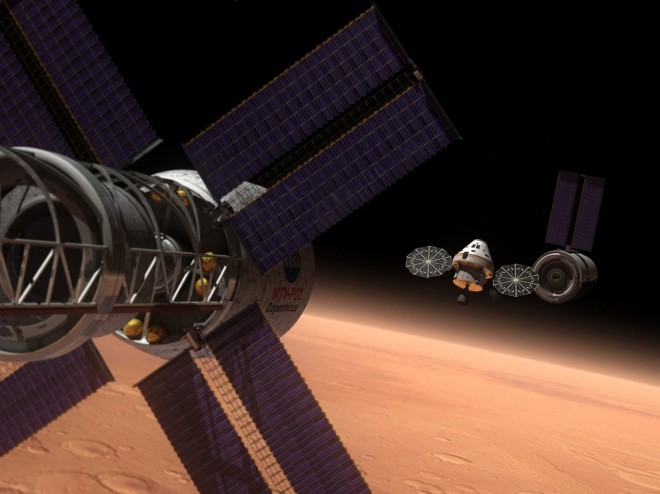

NASA's first study on the possibility of manned flight to Mars on a nuclear-powered ship (1960)

In November 1957, in the very same month, when the Soviet Union launched Laika, a small dog on board the 508-kilogram Satellite 2, about 20 engineers of the Lewis Research Center began researching the use of nuclear, ionic and rocket engines for interplanetary flights. On October 1, 1958, immediately after the formation of NASA, the Lewis Center came under the auspices of the Agency, and in April 1959 its specialists reported on their work to Congress, asking for funding for research on the possibility of flying to Mars. Congress agreed, giving the go-ahead to the first US study related to a manned flight to Mars on a nuclear engine.

In a report dated January 1961, which was supposed to give a brief description of their work, the researchers indicated that the flight was to begin with a near-earth orbit. The spacecraft itself, designed for 7 crew members, could either be launched from Earth assembled, or put into space in parts, assembled in orbit, and then sent on its journey.

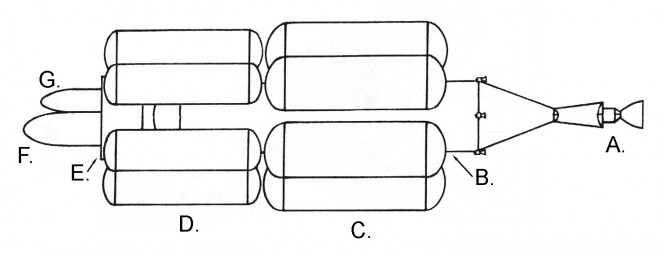

General view of a manned spacecraft. A is a nuclear rocket engine. B - central tank, C, D - clusters of liquid hydrogen tanks, E - crew compartment, F - Martian landing module, G - Earth landing module. NASA image.

')

After arriving at the target, the ship, using engines, had to slow down to the speed at which the gravity of Mars could capture it, turning it into an artificial satellite of the Red Planet for a while. Then, in anticipation of the next launch window, suitable for launching back to Earth, the astronauts were to descend onto the crimson surface of Mars in the cabin of the Martian Landing Module, which uses chemical rocket engines to descend and land. After spending some time exploring the surface of the planet, they then had to take off again to meet with the remaining spacecraft in orbit, which, once again launching the nuclear engine, would deliver the crew home to Earth. After returning to our planet from spacecraft, the Earth Landing Module would separate, which, having carried out a deceleration maneuver in the atmosphere, would deliver the crew to the Earth's surface, while the interplanetary spacecraft would fly further, heading for a safe “trash” orbit around the Sun.

In their report, the researchers focused on studying the influence of three interrelated factors (namely, the duration of the mission, the deceleration maneuver about the atmosphere, and the levels of radiation exposure permissible for the crew) on the final mass of the device at the time of its departure from the Earth's orbit.

Obviously, a shorter flight to Mars will require, in general, a larger amount of fuel (according to the plan of the researchers, it must be liquid hydrogen) than a longer one (for example, using the gravity of other celestial bodies to accelerate,) . On the other hand, in the case of a slow flight, one would have to take with him a greater amount of cargo — air, water and food — necessary for the crew. Ultimately, the researchers settled on a mission of 420 days, including a 40-day “waiting period” in Mars orbit. For purely analytical purposes, they even chose the start date - 1971 - but stressed that "this does not mean that any real flights will be scheduled for this time." A 480 km orbit around the Earth was chosen as the starting point.

The optimal launch date was chosen May 19, 1971 — when the delta V required for a flight from Earth to Mars would be 19.78 kilometers per second — given that acceleration and deceleration would be entirely due to the thrust of the nuclear engine. [1] In this scenario, the required Delta-V value would be achieved by heating the engine working fluid from the reactor, and throwing it out of the rocket nozzle. It is obvious, therefore, that the larger the delta V needed to be obtained, the larger the necessary amount of working fluid (liquid hydrogen) was. For comparison, for a 300-day mission, the required delta-V value would be 26.55 kilometers per second, and for a 950-day flight, only 12.39 kilometers per second.

[1] [Delta-V is understood as the difference in speed that is necessary to achieve in order to successfully conduct a maneuver. At the same time, the direction of the velocity vector is not taken into account, that is, if the spacecraft needs to accelerate from 0 to 1 km / s and then slow down again to 0, then the delta V will be 2 km / s, approx. Per.]

The authors showed that to reduce the flight speed of the apparatus, a maneuver for braking against the atmosphere is perfectly suitable, which will help reduce the mass of the ship [by the amount of working body mass that would otherwise be required for engine braking]. In theory, if the braking about the atmosphere was would be applied both on approaching Mars, and when returning to Earth, the delta V value that would have to be obtained with the help of an engine could be halved.

However, these figures are true only if we assume that the thermal shield, which was supposed to protect the crew from heating the ship when passing through the atmosphere, would not have mass. In practice, the deceleration maneuver was also hampered by the fact that in addition to the mass of the ship itself, it would be necessary to slow down the mass of the hydrogen in its tanks, which is necessary for returning to Earth. In this case, liquid hydrogen has a very low density, so large tanks would be needed to store it. Considering this, the calculated weight of the thermal board, which could protect the crew compartment and fuel tanks, was so large that a braking maneuver about the atmosphere of Mars would save 25% of the mass, and only about 3%.

Because of these difficulties, the researchers came to the conclusion that it would be more expedient to apply a drag on the atmosphere only when returning to Earth. Their 15-ton, 7-meter Earth Descent Module had to have a thermal shield that would burn on entering the atmosphere, thus taking away excess heat (this shield design was used on the ships Vostok, Voskhod, Gemini and Apollo, and continues to be used until now on the Unions and Shenzhou). At the same time, during braking, the shield would lose up to 10% of its own mass, and the crew would experience overloads up to 8g. Calculations showed that the weight of the thermal board in this case would be 6 times less than the weight of the working fluid necessary for similar braking with the help of the engine.

Turning to the issue of radiation, the researchers warned that “existing [at that time] knowledge in the field of the harmful effects of radiation cannot be considered exhaustive” [to put it mildly, expert opinion] . They listed the following factors, the influence of which should be considered: Van Allen belts around the Earth and Mars (in fact, Mars does not have radiation belts, but then did not know about it), cosmic radiation, solar flares and the ship’s own radioactivity.

The hydrogen exhaust should not only push the 67-meter ship toward Mars, but also serve as a kind of radiation shield. After the launch of a nuclear engine in Earth orbit, it will begin to take liquid hydrogen from the tanks of the ship. As planned by the researchers, two clusters of 6 tanks each were to be grouped around one central tank through which liquid hydrogen should flow into the engine. At the same time, as the central tank became empty, it had to be replenished with hydrogen from one of the clusters. This scheme ensures that there will always be a large amount of hydrogen between the engine and the crew compartment. After leaving the orbit of the Earth, half of the tanks in the cluster will be disconnected. The second half will fill the central tank during the departure from Mars, and will also be disconnected just before leaving the Red Planet.

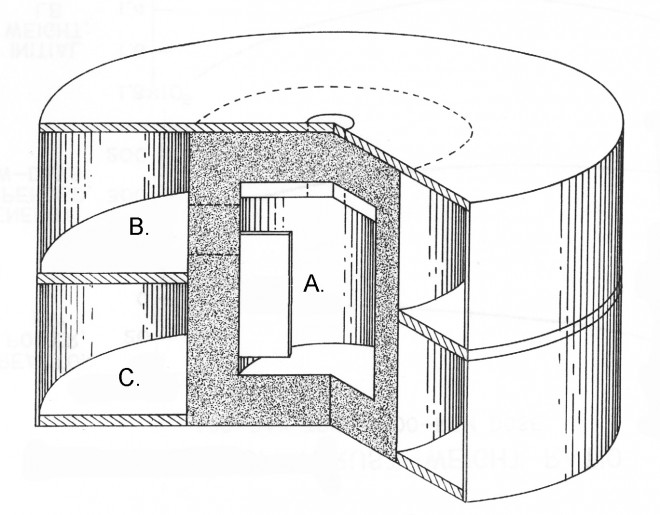

Image of the crew compartment. A - highly protected from radiation room, B - residential compartment, C - cargo compartment. NASA image.

The crew compartment is a light-protected double-deck “drum” with a total volume of 118 cubic meters, which was supposed to provide about 4,645 square meters of space for each crew member (“Something between the area that the officers have and the submarine officers have,” the report says ). In the center of the compartment is a highly secure "safe" with a volume of about 17 cubic meters. With the exception of this protected room, the entire crew compartment (5 meters high, 10 meters in diameter [the figures do not converge, but we leave it on the conscience of the authors of the original, approx. Per.] ) Will weigh only about 15 tons. The crew members will be located in the central protected compartment during the passage of the Van Allen belts, operations with a nuclear engine, as well as large solar flares. Sleeping crew will also be there to reduce the impact of cosmic radiation as much as possible. The researchers also took into account that 15 tons of supplies, placed around the central compartment, will serve as additional protection [apparently they thought that food should not be protected, —per. Per.] .

Obviously, of course, that the total mass of the “shield” necessary for the central compartment, strongly depends on what is the maximum amount of radiation allowed for the crew. Under the condition of avoiding large solar flares and an acceptable level of radiation of 100 Rem, a shield weighing 23.5 tons should have been enough. With a maximum allowable radiation dose of 50 Rems and the admissibility of one large solar flare, the shield mass would have already reached 140 tons. “These data,” the report says, “emphasize the importance of studying the effects and risks of cosmic radiation on humans.”

[It should be noted that in this issue, the researchers were quite optimistic. The English Wikipedia says that 100 Rems received in a fairly short period of time (though not specifying what it means to be “fairly small”) will lead to acute radiation sickness and death within a few weeks. According to the Russian Wikipedia, the liquidators of the Chernobyl accident received radiation doses of about 100 millisievert (despite the fact that “residents of certain regions of the Earth with an increased natural background receive radiation doses equal to about 100–200 mSv in 20 years”). 1 sievert (10 times more) is equal to 100 BeR. Of course, in the 1960s, the effects of human radiation were practically unexplored. If anyone has more accurate information on this topic, please write in the comments - comment. Per.]

Ultimately, the researchers concluded that “short flights would be more expedient (in terms of weight) than long-term missions”, even though such flights would require more fuel, since longer flights would require even more radiation protection the crew.

The researchers calculated that the mass of the ship for a 420-day flight, taking into account a radiation dose of 100 Rem, will be about 675 tons at the time of its intended launch from Earth's orbit in 1971.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/191570/

All Articles