Why balance the balance sheet?

If you know what a balance sheet is , you can finish reading on this. If the balance escaped attention, then, perhaps, you will be interested in its simple, at the same time unusual device.

Now I will briefly and, if possible, explain what the balance sheet is and why should it be balanced.

To begin with, the accounting department registers things used in business.

')

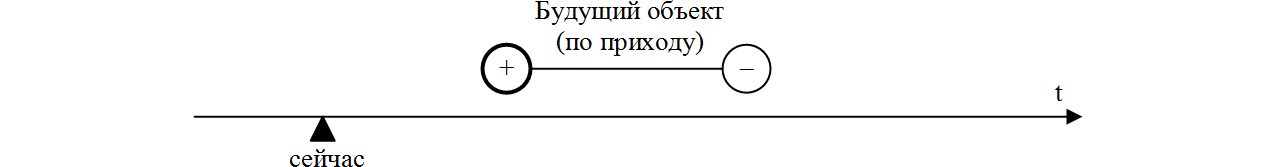

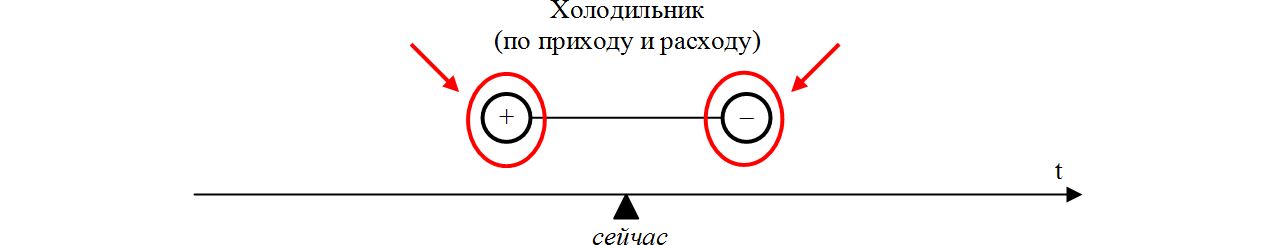

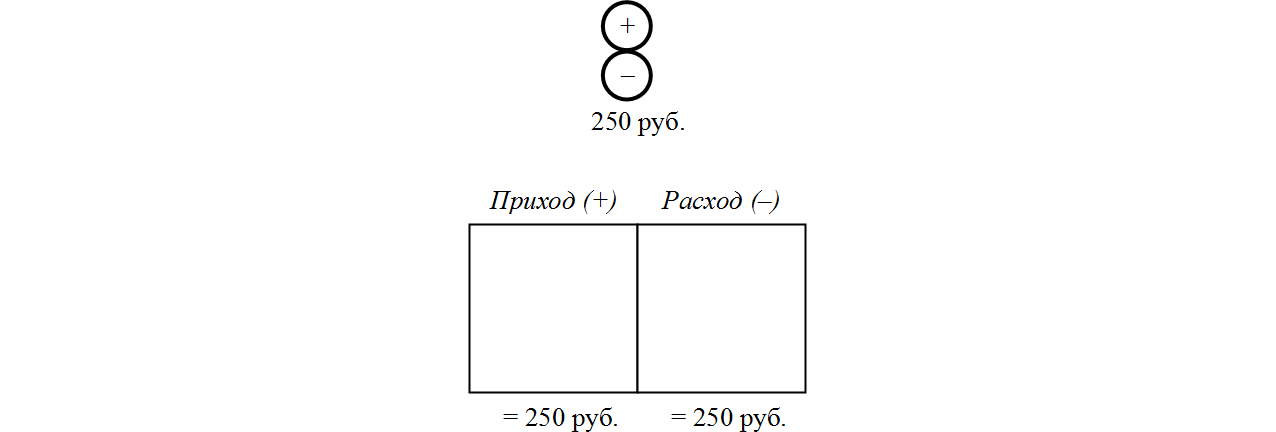

Well, it registers and registers, what does the balance have to do with it? Given that things come to the enterprise and drop out of it, thereby registering things is carried out twice: on arrival and expenditure. Each item registered in the accounting department has a receipt - the moment of arrival at the enterprise (conditional +), and an expense - the moment of departure from the enterprise (conditional -).

In the general case, the arrival of one thing is adjacent to the expense of another. This is due to one of two reasons:

• or by the law of conservation of matter (in relation to accounting, the case when a thing is renamed due to a change in characteristics, while it is considered that one thing has left, and the other has arrived in return),

• or trade exchange, when one thing is exchanged for another de facto.

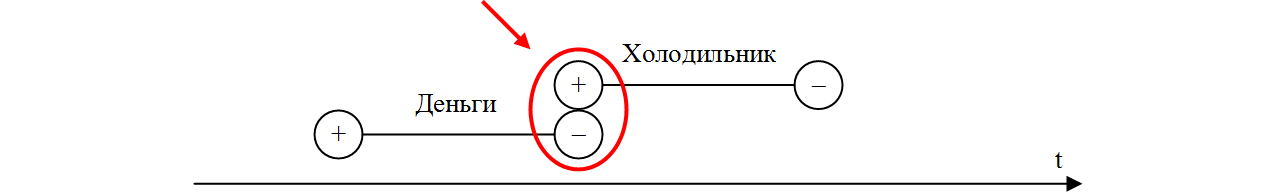

Take for example the second point: suppose we bought a refrigerator. This means: the money has dropped out, the fridge has arrived, all within the framework of a single business transaction.

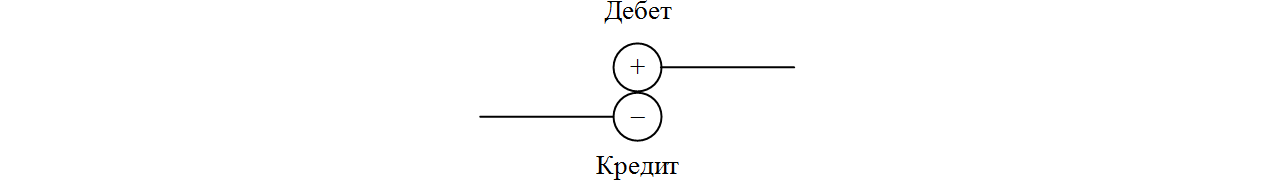

The arrival of one thing and the simultaneous consumption of another is, in aggregate, an accounting entry, or an accounting entry with their famous debit and credit .

In such a simultaneous registration of one thing for the arrival (debit) and the second for the expense (credit) is the essence of the so-called. double entry - but this is by the way.

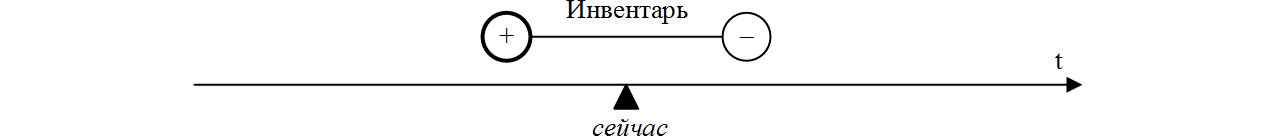

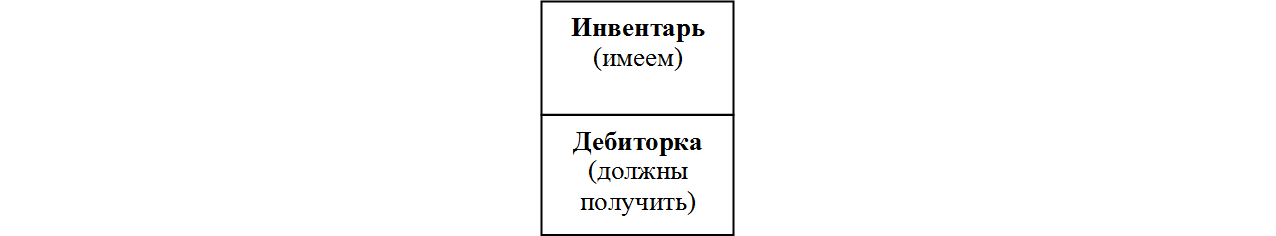

And what about the balance sheet? It shows the objects that appear on the enterprise at the moment. Such objects are called inventory. That is, inventory is things registered by arrival (those that have already arrived at the enterprise) and not registered by expense (those that have not yet left the enterprise).

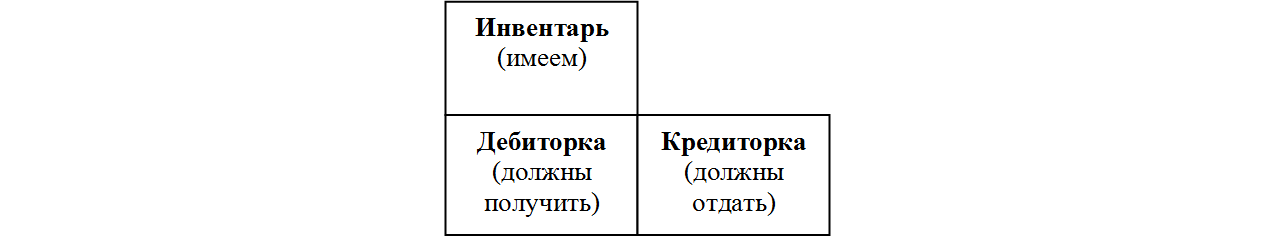

Let's designate the list of such things graphically, as a list.

What is here - in a simple list of things that satisfy certain conditions - maybe a balance? No, of course.

But wait.

In economic activities, not only cash items, that is, inventory, but also future items, which are expected to be received, are taken into account, for example, in connection with the contract. The formal difference from the inventory: registration is not the current receipt, but the future - the cash item (inventory) has already arrived, and the future thing is only expected to arrive, but it is still registered.

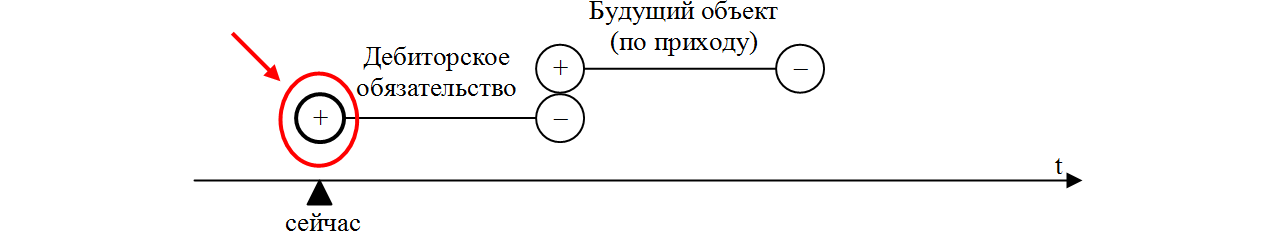

True, there is one subtlety, and substantial. Accounting does not know how to register objects with a future date: within one accounting entry-posting there must be one date — the current one. Therefore, instead of the future arrival of the object, the current obligation is recorded.

Inventory is what the enterprise has, and the receivables, or simply accounts receivable, are what the enterprise should receive. There is no such object as a receivable in nature, however, it means quite an existing thing, which, in accordance with legal norms, must be received by the enterprise (in the future).

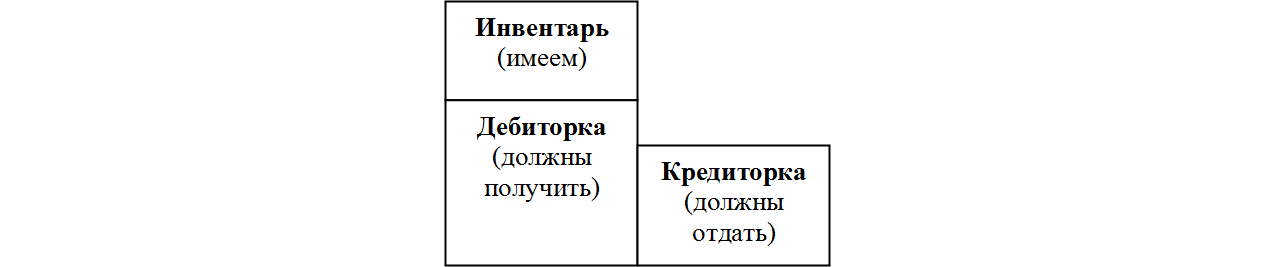

Understandably, one must be separated from the other.

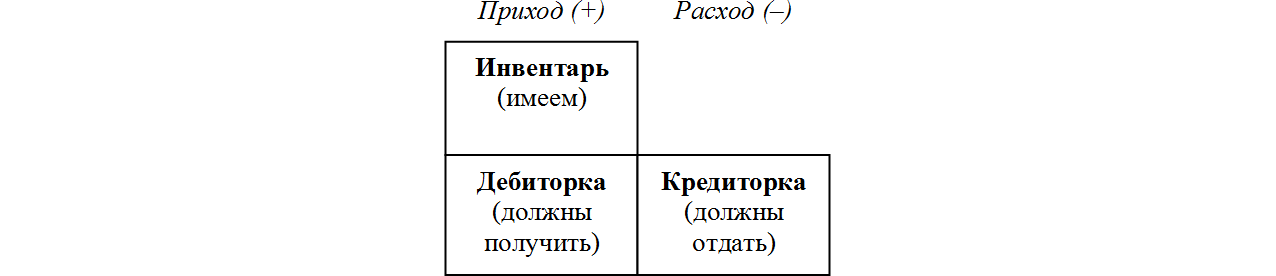

Why accounts receivable, and not just obligations? Because, in addition to the receivables, there is also a payable - accounts payable: that which the company must pay in accordance with legal norms.

In essence, this is the future expense of the object.

But due to the circumstances mentioned above, it is not the future expenditure of the object that is recorded, but the obligation - this time a creditor.

See what happens: normal things are always first recorded first by arrival, then by expense, and payable - first by expense, then by arrival. All the impossibility of registering two objects of the same accounting transaction by different dates, as a result of which it is not the future expense of the real object that is recorded, but some non-existent obligation. Here are the uncommon consequences of errors in the accounting methodology!

Since the credit card is opposite to the inventory and receivables by the sign (not a plus, but a minus), it is placed in a separate column in the graphic display.

Answer, is there a balance here (equality between two columns - positive and negative)? Not present and can not be present.

Within the framework of a separate enterprise, the three types of objects considered are not correlated at all. The ratio can be any - such, for example (favorable):

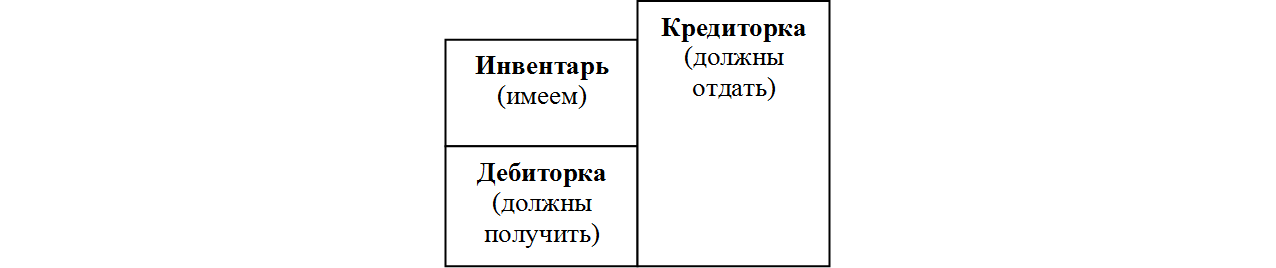

Or so (less favorable):

Or even so (which means: the company is actually bankrupt, since even having sold off all the property and having received it in full from the debtors, it will not be able to pay the creditors):

If the equality of positive and negative columns takes place, then this is pure coincidence, not a pattern in any way.

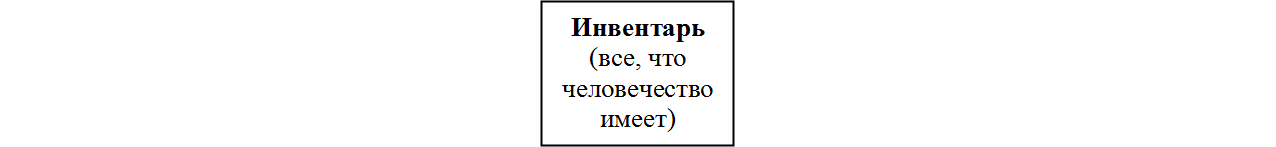

No balance, in short. But of course, only within one enterprise. If all the balance sheets of all enterprises and individuals are combined in one balance (as they say in accounting, consolidated), then it turns out ... what do you think? Balance in which there is one inventory.

Receivables and accounts payable are equal and opposite in sign: if someone has to give, then someone should get, and exactly the same. This means that with the consolidation of the balance sheets of all participants in economic activities, the accounts receivable and the payable will be credited to oneself, with the result that the inventory will remain - all the property involved in the economic activity of humanity. What was initially supposed to be, when we undertook to draw up a balance, one for all those involved in economic activities.

Here is another curious, purely accounting feature.

Imagine that a company has inventory — say, a refrigerator. Has - means, the refrigerator is registered on arrival. Suppose now that the enterprise has undertaken (under the contract, under the contract) to transfer this refrigerator and even receive money in advance for it, that is, there is an ordinary sale and purchase with a deferred transfer of the item. Essentially, the future consumption of the refrigerator must be recorded.

Don't you notice anything strange? The arrival of the refrigerator has been registered (in the past) and its future consumption must be registered for this refrigerator itself.

However, in accounting, due to its perverted methodology, there are two objects that seem to have no relation to each other: a cash object (a refrigerator) and a creditor’s obligation (to transfer the refrigerator to the buyer).

In both: the refrigerator is one, but two objects are registered, one positive (on arrival), the second negative (on consumption)!

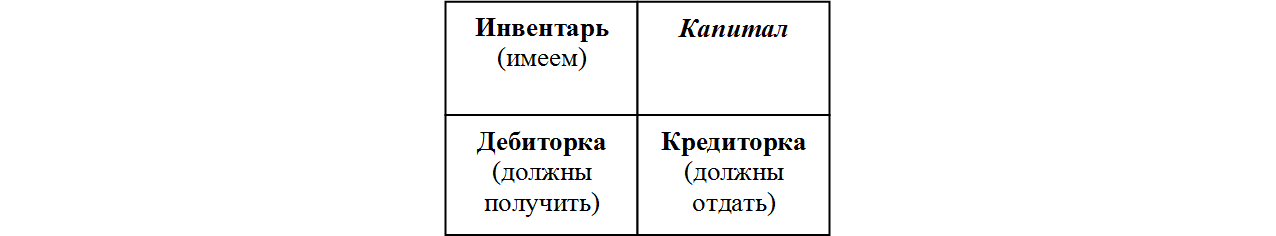

But enough about the poetic, back to the balance sheet, which is not clear how to get. As it was said, there is no balance and is not foreseen - there are two opposite signs, but categorically refusing to equalize columns:

Where does the balance come from?

You will not believe: it is created artificially. The missing part, under the name of capital , is placed in a smaller column - and the thing is in the bag.

This is achieved by registering capital as an object of accounting (although it was quite possible to calculate capital by calculation), as follows.

In general, changes in objects are interdependent and opposite in sign. Why - it was said: because of the trade exchange and the law of conservation of matter. However, there are business transactions in which one object should be involved instead of two: it is not possible not to perform such operations or not to notice them.

Suppose a thing is spoiled, I had to throw it away. There is, on the one hand, a decrease in inventory, and on the other hand ... whatever one may say, the second thing is missing.

The second thing is absent in nature and economic practice, but not in the accounting department, in which a fake object is registered under the name of capital: fake - because it simply replaces the absent object, that's all. Since the amounts of income and expense (debit and credit) of the accounting entries are always equal, there is a balance of positive and negative columns, from the very first accounting entry, whatever it may be. Suppose with this:

No subsequent changes can not shake this balance, since the effect on the balance columns is always equivalent:

or reduce and simultaneously increase one of the columns (such changes are called permutations );

or equivalently reduce or increase both columns simultaneously (such balance changes are called modifications ).

As you understand, equality is maintained due to the fact that the balance columns have different signs.

And now I repeat once again: the balance sheet is an artificial entity that has nothing to do with economic realities. In a real enterprise, there is no balance; it is achieved through artificial, for methodological purposes, filling in the missing difference by registering a non-existent object - capital.

Only one quote, known at the beginning of the last century, G.A. Bakhchisaraytseva:

“There is a striking lack of any common sense. Even more surprisingly, by “breaking up” the turnover according to the double-entry law, these accountants get equal results on Debit and Credit accounts and admire, saying: “This is another basic accounting law! The total of the left sides is equal to the total of the right sides ”(accounts). And this “independent” (!), From their point of view, of course, they call the law “the Law of Balance” or the “Law of the Balance of Accounts”. Could anything be naive! Add to two equal values equally, to get as a result equally and ... shout: “the main law of bookkeeping is the Law of Balance, as a result (?!) Of the law of double entry”! Lord mathematics calls these truths simply "axioms", and you are in vain and are carried away (and carry away others) with your short tails. "

In fairness it should be noted that there are dozens of so-called. counting theories , trying to justify the existence of the balance sheet as an objective phenomenon. It makes no sense to discuss them with non-specialists, since the "objectivity" of the balance sheet is obvious. Does anyone doubt that, in the event of a formal abolition of the balance sheet, entrepreneurs will stop using it?

In an amicable way, the balance sheet can be reduced to the simplest list of things — real, in their physical incarnation — indicating which of the things are present in the enterprise at the moment, which are to be received, and which are recoverable.

Such is the form of an objective, not an artificial balance. But of course, to call this reporting form a balance would be impossible.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/190376/

All Articles