Science under lock and key. First part

From the translator: Anyone who had to search the Internet for articles from scientific journals, probably faced with the fact that for access to a single article the publisher requires about $ 30. Sometimes the necessary article can be found in the public domain, sometimes not. At first glance, this is not surprising - any content is worth the money. However, scientific articles are quite different from movies, books and music.

Most scientific research today is done on state funds, that is, on our money. Most scientists, both those who wrote the article and those who checked and edited it, also receive salaries not from publishers. And, most interestingly, university libraries around the world, which are the main subscribers of the scientific press, also pay a lot of money for subscriptions to journals, which they themselves write. So large that even the Harvard University Library already publishes open letters about its plight.

')

This article contains a detailed analysis of the situation with the scientific press and the organization of scientific work in general. The article is quite voluminous, so I broke the translation into two parts. Here is a link to the second part .

The work of scientists usually follows a fixed pattern. They apply for grants, conduct research, and then publish the results in journals. This scheme is so familiar that it seems the only possible. But what if there is a better way to do science?

It is believed that by publishing an article, the scientist wants to share his results with the world. However, access to most published works is possible only for money. A subscription to scientific journals is worth thousands of dollars that only the richest universities can afford. Over the past couple of decades, the price of subscriptions has grown many times. Critics who oppose publishers believe that this rise in price is a consequence of the concentration of journals in the hands of private companies, which derive unfair profits from their dominant position in the market of scientific knowledge.

Having undertaken our own investigation of these alleged money bags from science, we have seen that for their opponents the struggle against this parasitic enrichment is only part of a more general process of reforming science.

Advocates of open science say that the modern model of scientific research that took shape in the 1600s requires changes that will enable science to fully share the results and collaborate via the Internet. When the entire scientific community will be able to communicate online without restrictions, the teams of scientists will have no reason to become attached to large bureaucratic structures and adjust the time of publication of their work under the timetable for the publication of journals.

Subscriptions limit access to scientific knowledge. And while the path to the heights of scientific career and prestigious positions lies through publications in reputable journals, cooperation with other scientists, crowdsourcing of complex scientific problems and free access to experimental data sets will not interest anyone. Practices established in the 17th century inhibit science in the 21st century.

The emergence of scientific journals

If I saw farther than others, it is because I stood on the shoulders of giants.

Isaac Newton

In the 17th century, scientists often kept their discoveries secret. It is known that Gottfried Leibniz challenged the primacy of Newton in the creation of differential and integral calculus, since he did not publish his discoveries for several decades. Robert Hooke, Leonardo da Vinci and Gallileo. Galileo published only encrypted messages in order to have proof of their priority. The only benefit from the publication was the opportunity to prove their primacy. Therefore, they preferred not to publish their work in clear text, and gave the key to deciphering only after someone else made the same discovery.

It was around this time that public funding and publication of works in scientific journals began. Rich philanthropists and kings jointly created scientific academies such as the Royal Society for the Development of Nature Knowledge or the French Academy of Sciences in London, which allowed scientists to conduct research in more stable and secure conditions. Patrons wanted their money to contribute to the development and dissemination of scientific ideas for the benefit of the whole society.

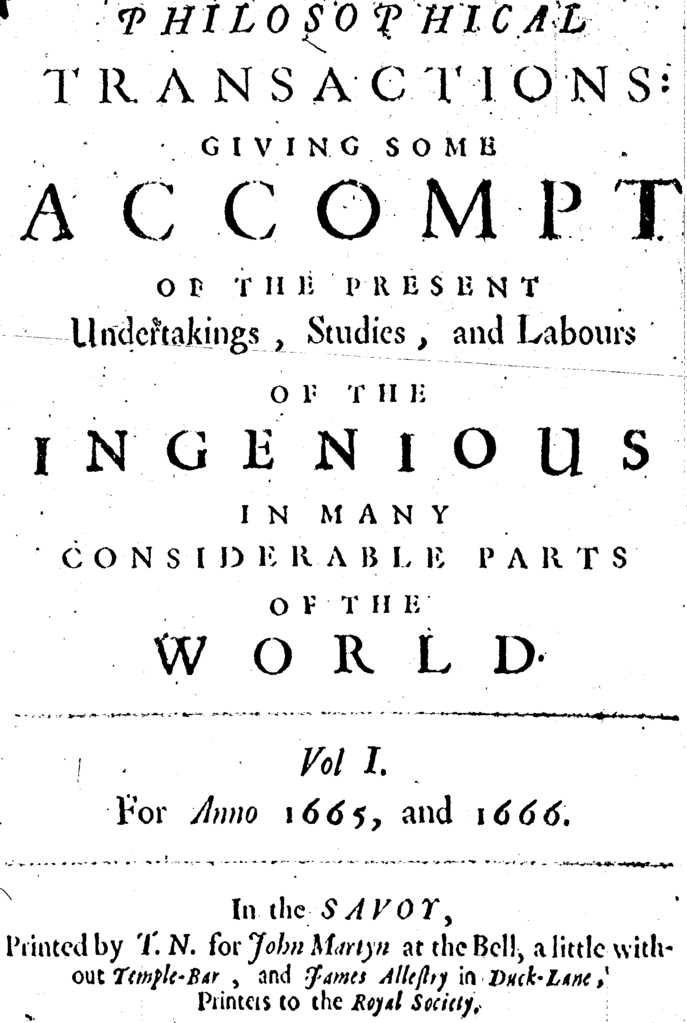

Scientific journals appeared in the 1660s at the academies, as an effective means of disseminating their discoveries. The first one was released by Henry Oldenburg, secretary of the Royal Society, for his own money. In those days, the market for scientific publications was very small, and printing a magazine cost a lot of money. Scientists provided their articles for free, as the publisher did a very important and complex matter, often working at a loss. From the beginning of the formation of the market of scientific publications and almost until the middle of the XX century, almost all scientific publishing houses were non-profit organizations, often in academies and institutes. Their revenue was low, and private publishing houses remained rare.

Now universities, not academies, have become the dominant academic institutions. Due to the increase in the cost of research (for which now it is necessary to build particle accelerators and the like), the main sponsors of science now are not private philanthropists, but the state, through a system of grants. And magazines have turned from a means of disseminating knowledge into an indicator of prestige. Today, the most important part of a scientist’s resume is his publication history.

Many scientists work in the private sector, where the main incentive for doing science is the profit from intellectual property created by scientists.

But, if we exclude applied research that gives a fast commercial result, the system that appeared in the 1600s remains almost unchanged. Michael Nielsen, a physicist and writer, notes that this system gave rise to "scientific culture, which to this day has encouraged the publication of discoveries in exchange for prestigious jobs and authority ... Over the past 300 years, it has changed surprisingly little."

Monopolization of science

In April 2012, the Harvard University Library published a letter in which the situation with subscriptions to scientific journals was called "financially unbearable." Librarians stated that due to a 145% increase in prices over the past six years, they will soon be forced to abandon part of their subscriptions.

The Harvard Library called those who are primarily responsible for the emergence of financial problems: “The situation is aggravated by the constant attempts of some publishers to buy, combine and raise prices for scientific journals.”

The most famous of these publishers is Elsevier . This is a real giant. Each year, Elsevier publishes 250,000 articles in 2,000 journals. In 2012, its revenue reached $ 2.7 billion. His profit of more than a billion dollars was 45% of the total profit of the Reed Elsevier Group - his parent corporation, which is 495th in the world in market capitalization.

Companies like Elsevier appeared in the 1960s and 70s. They bought scientific journals from non-profit scientific organizations and turned them into a successful business, making a bet that it would be possible to greatly increase prices without losing subscribers who have nowhere to go. Today, only three publishers — Elsevier, Springer, and Wiley publish about 42% of the articles on the 19 billion market for science, technology, and medicine magazines. 80% of their subscribers are university libraries. Since each article is published in only one journal, and scientists need access to any significant article in their industry, libraries are forced to buy subscriptions without looking at the price. Only from 1984 to 2002, prices for scientific journals increased by 600% . And according to some estimates, the prices of Elsevier-owned magazines are 642% higher than the market average.

Publishers also bundle magazines. Their opponents argue that this forces libraries to buy subscriptions to less prestigious journals, as they go to a load that is really necessary. Moreover, there are no fixed prices for these packages - the publishers form them individually for each university, depending on the history of past subscriptions.

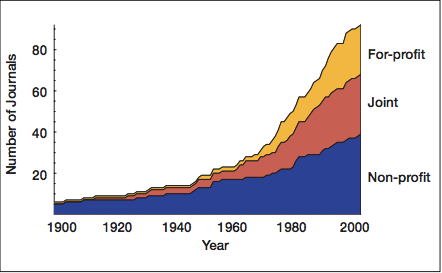

Growth in the number of commercial journals in the field of ecology

over the past hundred years according to ISI

Such tactics turn Elsevier and their ilk into an evil empire in the eyes of critics — professors, librarians, students, independent researchers, scientific companies, and simply curious people whose attempts to gain access to scientific knowledge run across money fences erected by publishers. They cite two main objections to price increases.

The first is that prices are rising at the time, as the Internet has made the dissemination of any information easier and cheaper than ever.

Secondly, universities are forced to pay for the results of research that they themselves produce. Universities establish grants and pay salaries to scholars writing articles. Even the review and verification of the value and correctness of the articles, which Elsevier refers to, as the main source of the added value of their journals, is usually carried out on a voluntary basis by scientists who are paid at universities.

Elsevier actively opposes attempts to question the legitimacy of his strategy, refuting the arguments of critics and insisting that they "work in partnership with the community of scientists, making a stable and meaningful contribution to science." In an investment analysis report on Reed Elsevier, Deutsche Bank summarizes their arguments :

Justifying a high rate of profit, publishers point to highly qualified personnel who preliminarily review articles before submitting them for review; support that they provide to reviewers, including small fees, complicated layout, printing and distribution, including the cost of publishing on the Internet and hosting. In total, Reed Elsevier employs about 7,000 people. In addition, a high rate of return reflects the company's performance and economies of scale.

How fair are these arguments?

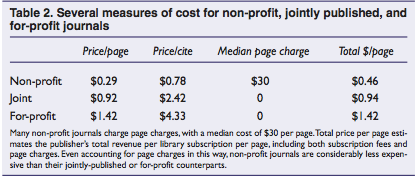

One way to check is to compare the real value of commercial magazines with non-commercial ones. For example, in the field of ecology, the price per page of a commercial magazine is three times higher than the price of a non-commercial one. And if we compare such an indicator as the ratio of price to the number of citations (this is an indicator of the quality and significance of the article), then non-profit journals are five times better.

One way to check is to compare the real value of commercial magazines with non-commercial ones. For example, in the field of ecology, the price per page of a commercial magazine is three times higher than the price of a non-commercial one. And if we compare such an indicator as the ratio of price to the number of citations (this is an indicator of the quality and significance of the article), then non-profit journals are five times better.Another way is to look at margin. 36% of Elsevier is much higher than the average for business of periodicals 4% - 5%. It is hard to imagine that in an industry that has existed for more than a hundred years, no one is able to work with lower margins. In the aforementioned report of Deutsche Bank, similar conclusions were made:

We are confident that Elsevier makes a relatively small contribution to the publishing process. We do not want to downplay the importance of the work that 7,000 of its employees do, but if their work really was so complicated, expensive and necessary, as publishers claim, they would not be able to get 40% of the profits .

Libraries and before faced with the problem of the high cost of subscriptions to scientific journals. So, back in 1998, The Economist wrote about this . But now even the richest universities cannot afford access to the entire body of scientific knowledge. And this is despite the fact that they themselves produce this knowledge by the forces of their own employees.

The second part of the translation .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/189944/

All Articles