YAF - language reporting forms

Thirteen years ago I invented YAOF, the language of reporting forms, and even included it as a chapter in my accounting textbook.

No, no, I do not intend to make laugh the respected habravchan samples of the "code", the benefit immediately after his birth YAF safely died, no one is interesting and not necessary, even to its inventor. The language passed away, but the problem that he was trying to solve, due to the fact that few people worked on her and were not working on her now, remained unresolved. The solution to this problem may be of some interest not only for accountants, but also for programmers.

')

Now I will try to explain what is the matter.

Who among you has not seen accounting reports - countless and indigestible forms that accountants fill out with financial indicators ?! It was clear to me from the very beginning: since the forms are built on the basis of a database that has a certain structure, there should be some typical algorithms for their construction - not particular ones for each case, but typical ones. The idea was to replace the textual and tabular description of accounting reports, in which each indicator is calculated separately, with a formal mathematical description, in which any report is the result of standard procedures performed with the original base.

I don’t dare to give here the “code” invented by me because of its complete helplessness, but I still have not refused the logic that moved me at that far moment to this day. Perhaps, my reasoning will push one of the IT people to practical thoughts. In short, information for consideration.

Having decided to create a language of reporting forms, I first of all divided the reports into unstructured and structured:

- in unstructured reports, indicators, each of which is calculated in a separate way, are placed in tables or arranged on a sheet in an arbitrary manner, accompanied by textual names and explanations;

- structured reports - on the contrary, reports with a clear structure: in the form of tables obtained from the source database through some of its transformations.

I had to abandon the formalization of unstructured reports, due to their obvious “non-computer” to me.

“Only structured reports, only converted tables,” I immediately set for myself, but the conversion came up against the absence of the original sample.

It is easy to transform something into something when the initial structure is known, and if not? What to do if there are many ways to register credentials and a virtually infinite number of possible structures? I remind you that I was interested in typical methods of transformations, as a result of which it would be possible to get the form of a report not in the form of a form with instructive explanations, but in the form of software - understandable not only to the programmer, but also to the accountant - code. There was only one way out: to take some structure as a model and to make a start from it. In this case, the accounting bases with the standard sample structure could be used when generating reports directly, and the base with a non-standard structure was required initially to be reduced to a base with a standard structure.

I called the base with the standard structure a normalized table . Reduction of any accounting base to a normalized table was possible, since any of the bases I was interested in was accounting: certain objects were registered in it, which required a certain data structure expressed by the list of properties and gauges.

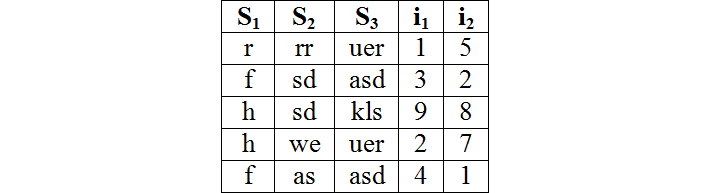

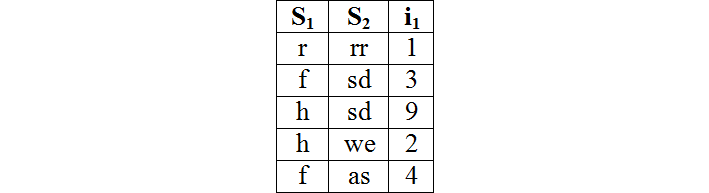

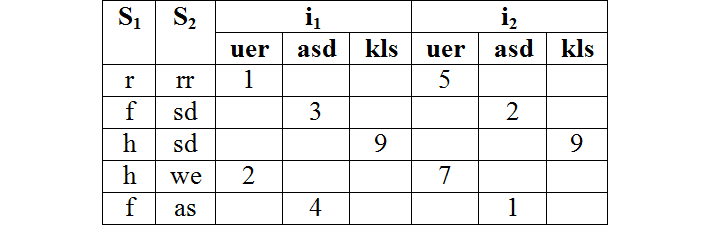

In the following simplest normalized table, each row represents one object, S is the properties of objects, and i are meters:

It is quite obvious that, no matter how sophisticated the structure of the accounting database, in the final (simplest) version it all comes down to registering an object, describing its properties and meters.

Strictly speaking, meters are not a mandatory element of the accounting database: a base meter is a meter — a quantity — can be obtained by converting a table as the number of object records after sampling.

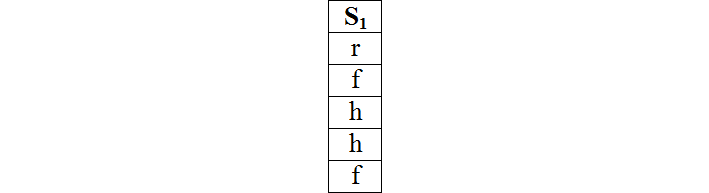

Suppose i1 and i2 denote something different, not the number of objects, but we need to operate on the number of objects according to the S1 property. Throwing away the properties we don't need, we get a table for conversion.

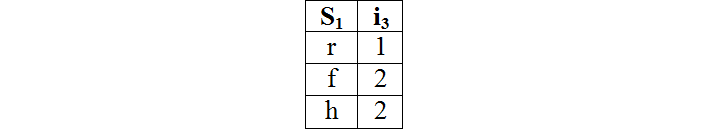

Then we perform the conversion, counting the number of objects (i3) with each value across the field S1.

There is a new meter that was not in the original table.

Similarly, average values can be obtained.

But suppose all the necessary gauges in the source table are in place — one wonders what typical conversions are necessary when generating accounting reports? I asked myself this question and for a long time tried to reduce the diverse accounting reports and statements that I know (fortunately, only structured ones) to model conversions.

Some of the necessary conversions — first of all, permutation of the table columns , transposition , selection and sorting — I immediately omitted because of their obviousness: I was interested in true accounting methods. As a result of long-term reflections of those, only two were found.

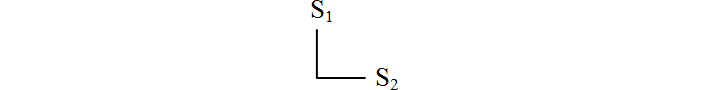

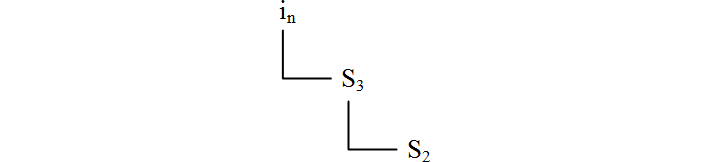

The first one is quite well-known: setting properties according to hierarchy .

We take the initial data (we use only the properties S1 and S2 and the meter i1 - that is, after some sampling):

We set the following hierarchy:

We have as a result of the transformation:

In accounting in such cases it is customary to write: including ...

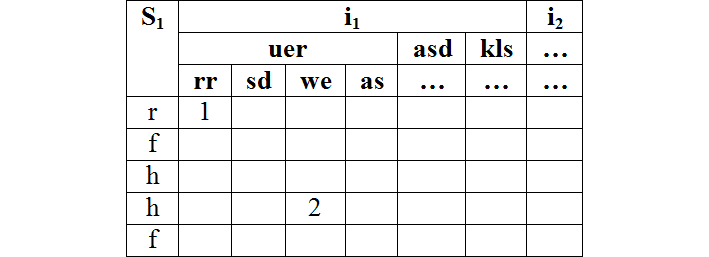

The second way is to put a property in the heading (this method did not have a name in accounting or computer science, I had to invent it myself).

This is about the following.

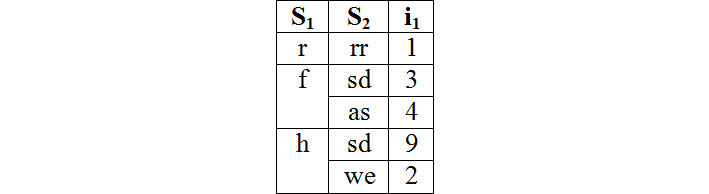

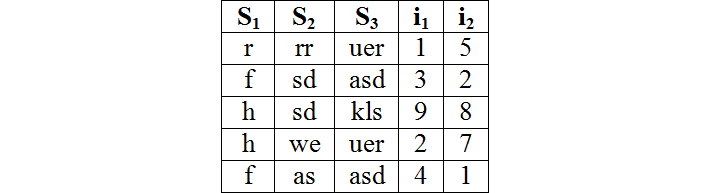

Take our original normalized table:

Then one of the properties of the object — say, S3 — is put into the header, into the area of the meters, with the following result:

The data are identical, but the table view is completely different. Why not, if the reporting user wants so much - to whom the reporting data are intended for?

Obviously, according to the hierarchy, it is possible to make a header according to the hierarchy - to set such a hierarchy, for example:

In this case, the following table view will appear (the fragment for the first branch is given):

As far as I understand, the same thing could be obtained by transposing the table and setting its hierarchy: it means that the heading is the final result of the transformations performed in a certain sequence.

The remaining possible transformations of the normalized table — for example, the result rows — are more designer.

In the considered examples, the simplest source data is used: in real practice, the database is complicated by the date and income-expense (in the distorted accounting version by debit and credit), and the income and expense of one object are not recorded simultaneously. Thus, the object is registered twice: once on arrival, the second time on consumption. Meters, calculated by the incoming, but not retired objects form a balance (and colloquially, balances). However, this meter does not add anything fundamentally new to the table conversion capabilities.

Structured reports can be reduced to named elementary transformations.

It seems to me that if the need arises for a language of reporting forms, such a language could be written fairly quickly, and not an absolute amateur in programming like me, but quite a qualified companion. If this is ever implemented, the accounting report forms will take the form of program codes, which is welcome in the light of computerization. A completely different question is how much it is necessary for people making decisions in the field of accounting. Some very modest movements in the direction of computerization of accounting standards are made, but they can hardly be called sufficient and adequate.

PS Having finished the article, I tried to figure out which of the accountants or programmers solved (at least could solve) the same problem.

Two accountants come to mind, well-known people in accounting.

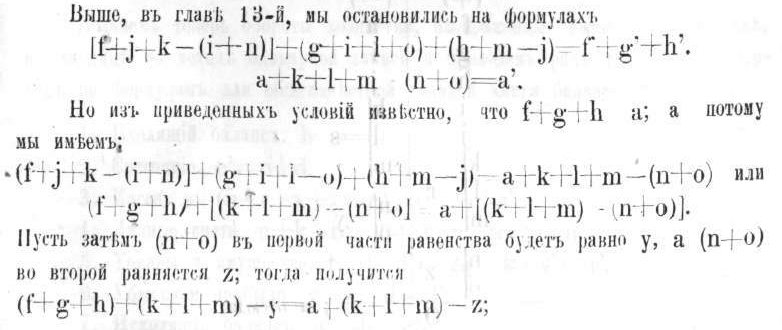

The first is Nikolai Ustinovich Popov (1843 -?). Although he lived for a long time and solved the problem of not formalizing the reporting forms, but the mathematical substantiation of individual accounting systems. In those days, programming was difficult, but there is no doubt, if Nikolai Ustinovich were our contemporary, his mathematical abilities would have found application.

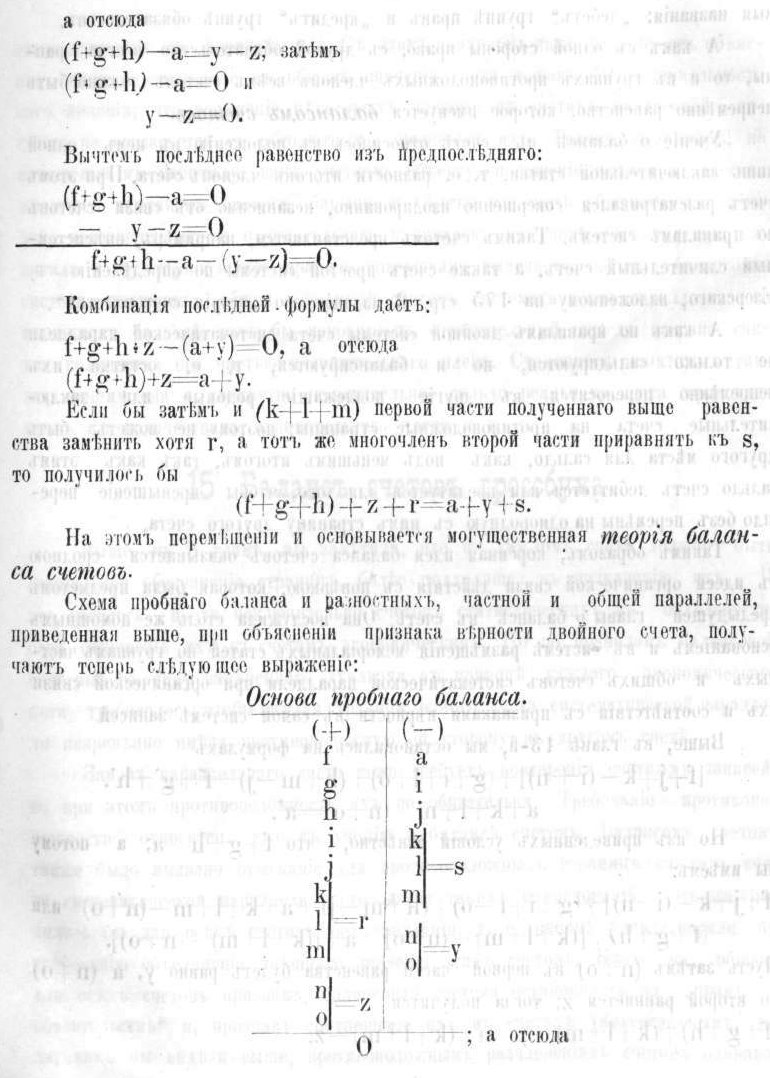

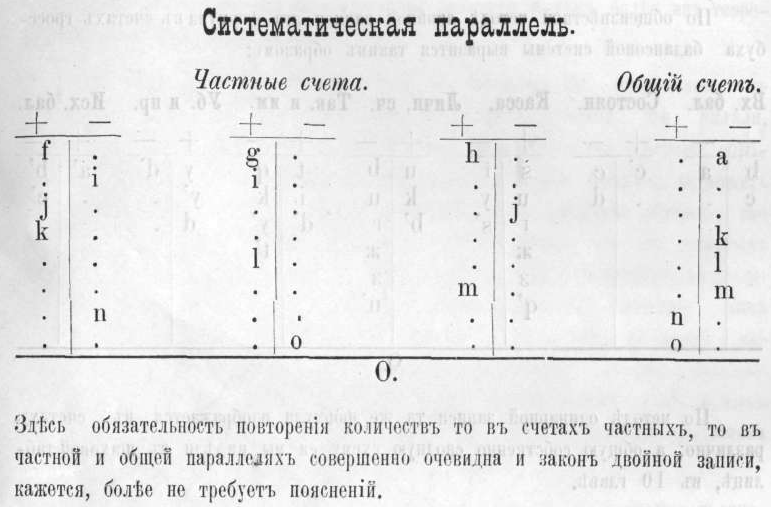

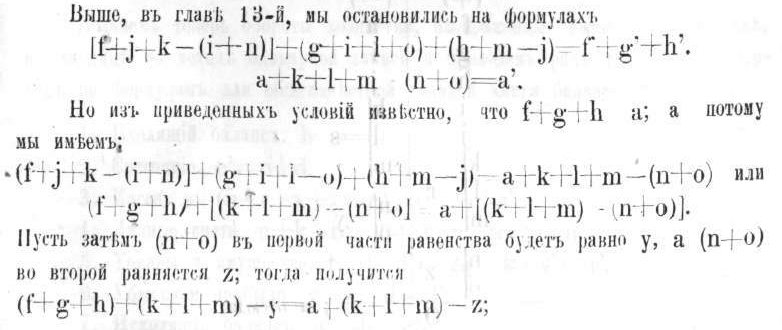

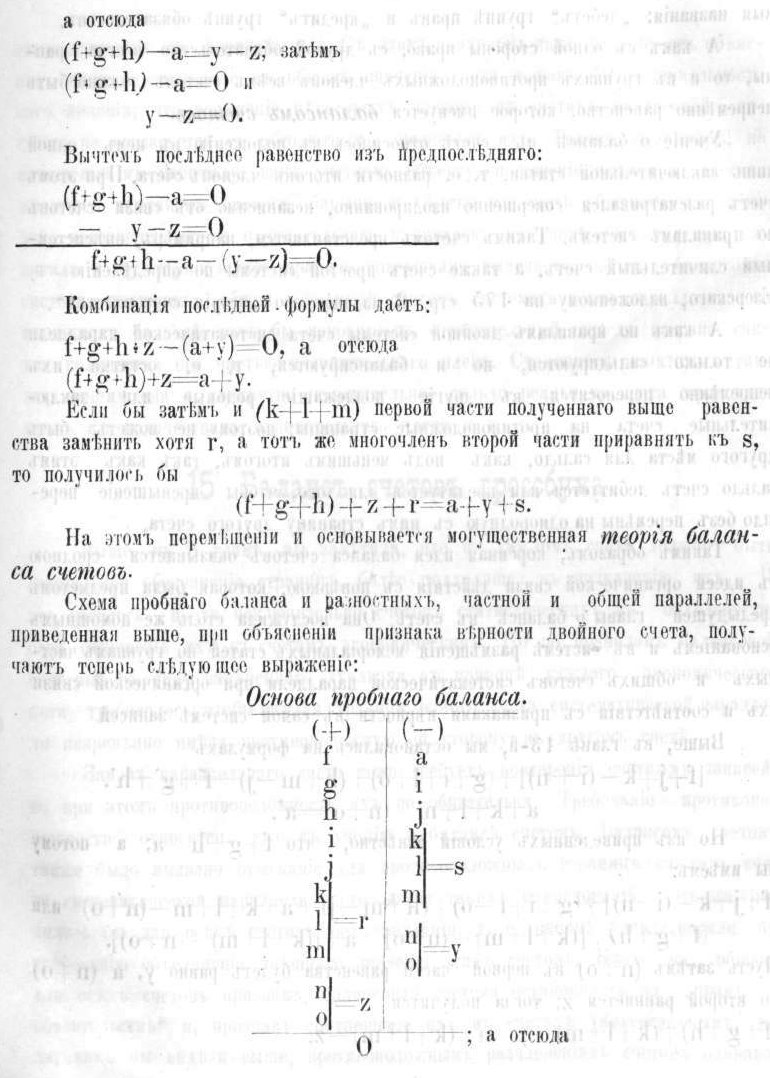

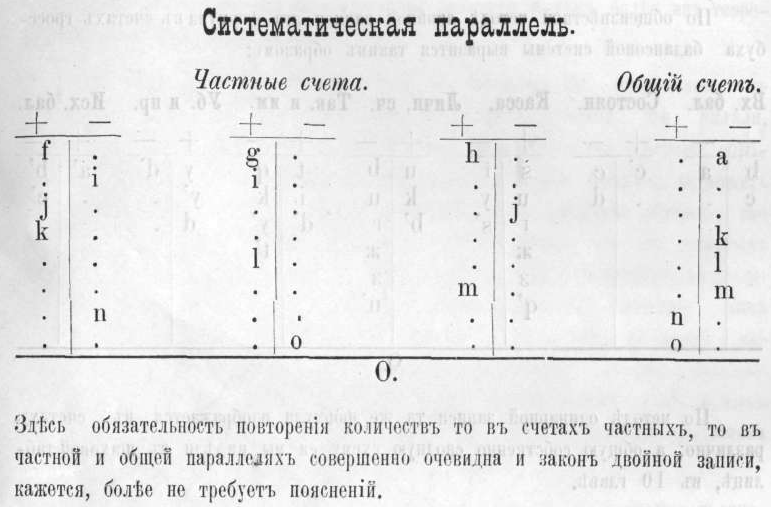

Under the spoiler a couple of pages from the book N.U. Popov's "The Mathematical Method of Accounting" (1906), so that habravchane could assess what categories this person thought.

Watch

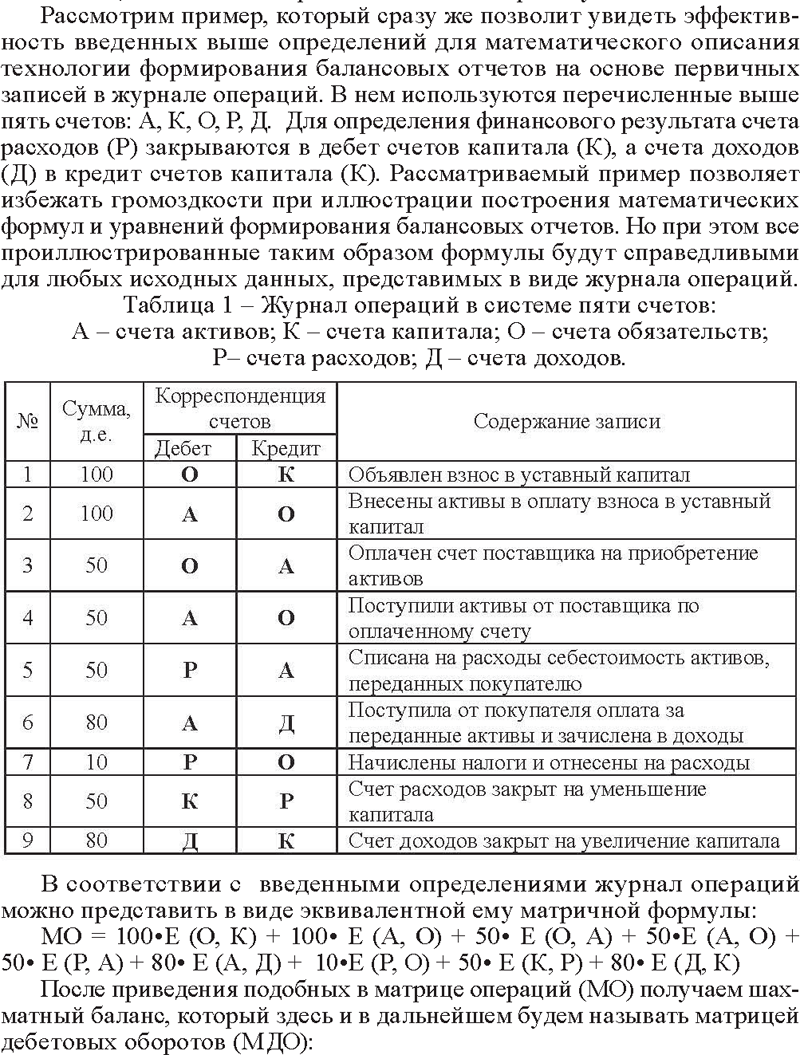

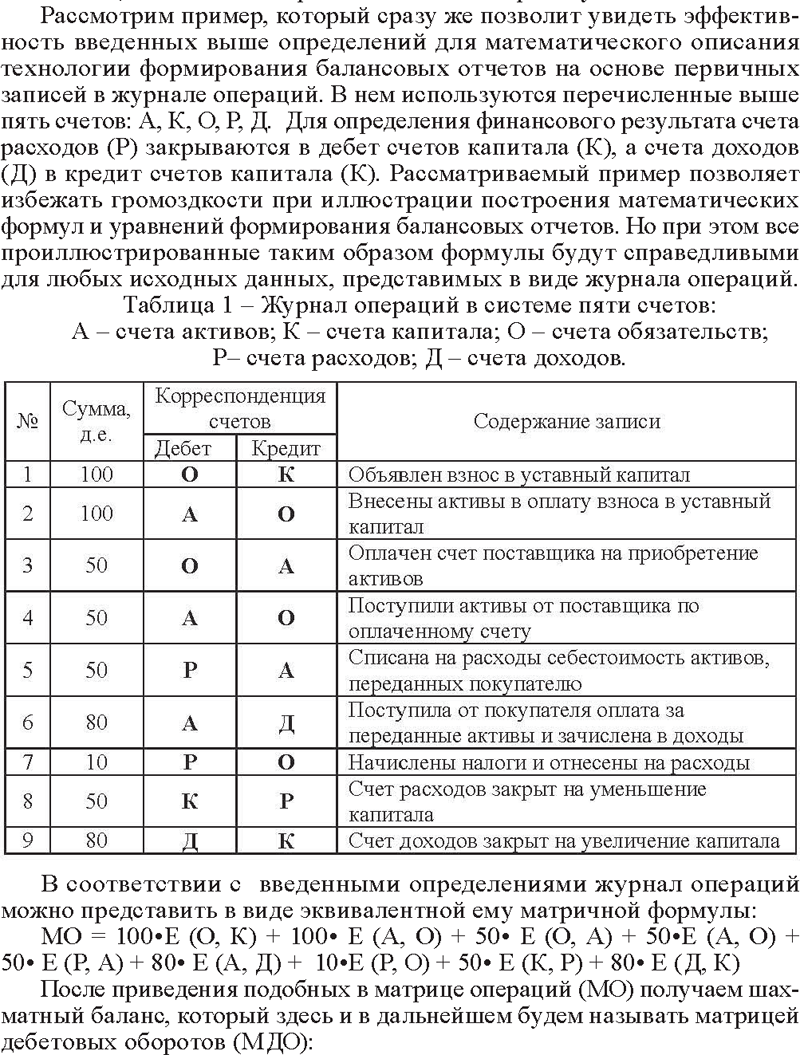

The second accountant who solved (and successfully solved!) The problem of formalizing accounting reports is our contemporary, Professor Oleg Ivanovich Kolvakh (born 1946). According to his concept, accounting reports (initial data, too) are formalized within the framework of matrix algebra, hence the name of the system - matrix accounting .

Under the spoiler, two pages from O.I. Kolvaha "Matrix model of accounting and the formation of balance sheets."

Watch

Matrix Accounting O.I. Kolvaha was created before my accounting textbook, I was not familiar with it then, otherwise I would refrain from inventing YAF. Unfortunately, matrix accounting, with all my own, as far as I can judge of mathematics, mathematical rigor has not received practical application.

In accounting practice, languages associated with accounting software are used, primarily with “1C: Enterprise”. As far as these languages are suitable for use as a universal language of reporting forms, I do not know because of the weak acquaintance with them. Attempts by professional programmers to write such a language — not at the request of employers, but on their own initiative — are unknown to me.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/188262/

All Articles