The open source community is leaning toward more liberal licenses.

30 years ago, when the production of computers and software for them has long ceased to be the prerogative of scientists only and turned into a serious business, in an academic environment they were surprised to find that they can no longer use computer programs as easily as they used to. Increasingly, scientists, students and enthusiasts have stumbled upon copyrights and proprietary licenses that prevented them from studying and modifying an increasing amount of software. It was at this time that one of the staff of the MIT artificial intelligence laboratory, Richard Stallman, formulated the basic principles of the free software movement. A few years later, in 1988, the GNU GPL license was written - the most radical free license, which obliged to open all software created on the basis of or using code licensed under the GPL.

At that time, it served as a kind of “ramming” that broke free software and did not allow to blur and mix free software with non-free software. But times have changed. Today, free software has proven its competitiveness and is widely used by governments and large commercial corporations around the world. Studies of open source statistics suggest that now more and more programmers are choosing the most liberal licenses, like the MIT license, which are allowed to do almost anything with the program. So, on Gitkhab, 85% of the repositories do not contain any indication of the license at all, and among the rest 15%, the MIT license is leading by a large margin.

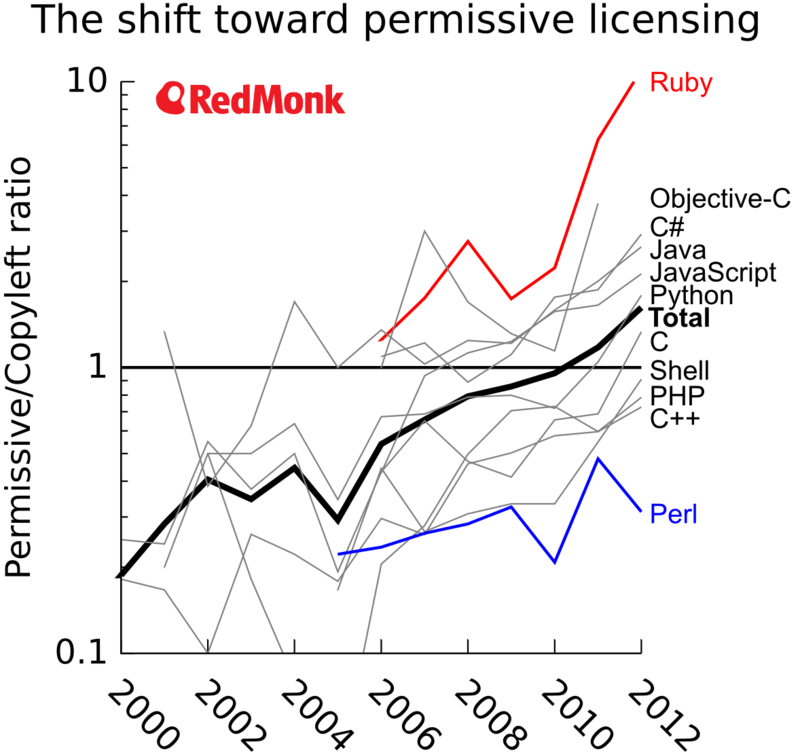

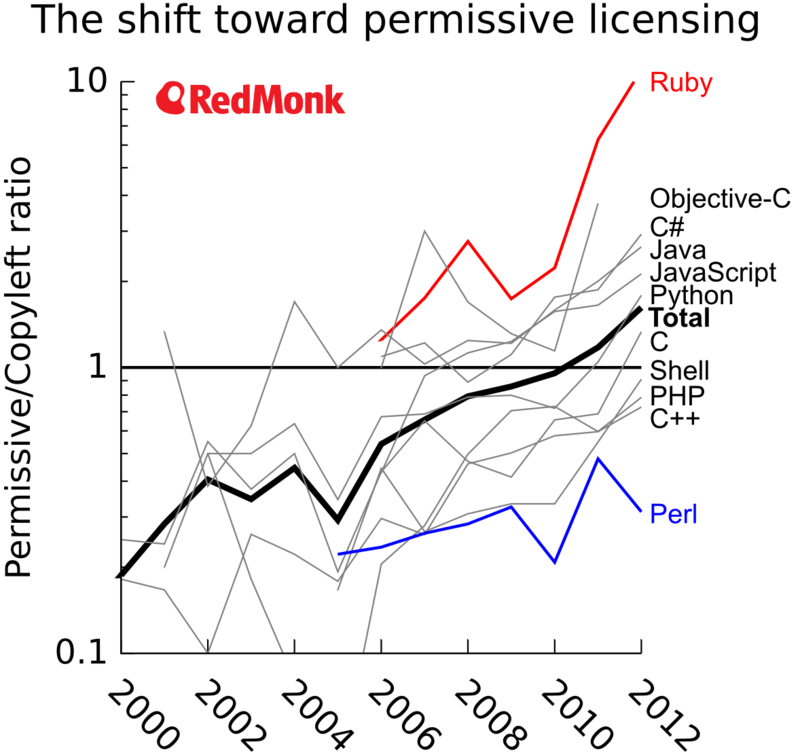

An analysis of 57,930 active Ohloh open-source wiki-catalog projects conducted in July 2012 showed that the trend towards more liberal licenses has been very stable for more than a decade. The type of license was determined in 17,549 projects. Licenses were divided into three groups - liberal (BSD, Apache) copyleft (GPL, AGPL) and limited (LGPL, MPL, EPL). The latter group was very small, so it was excluded from the results. Graphs of changes in the ratio of the number of projects with liberal licenses to the number of projects with copyleft licenses were compiled for eleven of the most popular languages:

')

The vertical scale shows this relationship on a logarithmic scale. Values greater than one correspond to the predominance of liberal licenses, less - copyleft. Almost all languages are quite a dense group, and the total number of liberal licenses exceeded the number of copyleft licenses after 2010. Two languages stand out strongly: Perl, which surprisingly steadfastly adheres to copyleft ideals, and Ruby, the projects for which are licensed almost exclusively under liberal licenses.

If earlier the creation of free software was primarily under the banner of GNU / Linux, and the majority either had to use copyleft or licensed software in a generally accepted manner at that time, the last decade has become the era of web development, and programmers, not having such an authoritative sample for imitation, like Linux, they simply chose the shortest and simplest license options. Perhaps the shift in licensing strategy is precisely this. Or maybe some programmers think that there is no longer any need to protect free software as aggressively as the GPL does.

In any case, any license is better than no complete license. After all, without an explicitly specified license, your project actually stops being open. When publishing a code that at least theoretically could be useful to others, do not forget to specify a license - this will relieve your colleagues from many troubles.

At that time, it served as a kind of “ramming” that broke free software and did not allow to blur and mix free software with non-free software. But times have changed. Today, free software has proven its competitiveness and is widely used by governments and large commercial corporations around the world. Studies of open source statistics suggest that now more and more programmers are choosing the most liberal licenses, like the MIT license, which are allowed to do almost anything with the program. So, on Gitkhab, 85% of the repositories do not contain any indication of the license at all, and among the rest 15%, the MIT license is leading by a large margin.

An analysis of 57,930 active Ohloh open-source wiki-catalog projects conducted in July 2012 showed that the trend towards more liberal licenses has been very stable for more than a decade. The type of license was determined in 17,549 projects. Licenses were divided into three groups - liberal (BSD, Apache) copyleft (GPL, AGPL) and limited (LGPL, MPL, EPL). The latter group was very small, so it was excluded from the results. Graphs of changes in the ratio of the number of projects with liberal licenses to the number of projects with copyleft licenses were compiled for eleven of the most popular languages:

')

The vertical scale shows this relationship on a logarithmic scale. Values greater than one correspond to the predominance of liberal licenses, less - copyleft. Almost all languages are quite a dense group, and the total number of liberal licenses exceeded the number of copyleft licenses after 2010. Two languages stand out strongly: Perl, which surprisingly steadfastly adheres to copyleft ideals, and Ruby, the projects for which are licensed almost exclusively under liberal licenses.

If earlier the creation of free software was primarily under the banner of GNU / Linux, and the majority either had to use copyleft or licensed software in a generally accepted manner at that time, the last decade has become the era of web development, and programmers, not having such an authoritative sample for imitation, like Linux, they simply chose the shortest and simplest license options. Perhaps the shift in licensing strategy is precisely this. Or maybe some programmers think that there is no longer any need to protect free software as aggressively as the GPL does.

In any case, any license is better than no complete license. After all, without an explicitly specified license, your project actually stops being open. When publishing a code that at least theoretically could be useful to others, do not forget to specify a license - this will relieve your colleagues from many troubles.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/183496/

All Articles