British scientists are dissatisfied with government policies regarding copyright

England is considered one of the most prosperous countries in terms of copyright. Analysts believe that the level of piracy there is minimal.

In 2011, Professor Hargreaves, who led a group of independent researchers, published a report commissioned by the government, which had to answer whether the country was going in the right direction in the direction of intellectual property, and specifically, whether the existing system contributes to progress and economic growth.

')

Already in the preface the professor writes that if the government orders such a report, it means they doubt that everything is going well. It seems that despite numerous reviews made in the last 5 years, the government is not listening to the recommendations made, and continues to pursue a copyright policy under pressure from lobbying, and not on the basis of objective factors.

The authors thought: maybe British politicians simply do not believe British scientists? Then they decided to announce an unprecedented action call to collect opinions (Call For Evidence) on the current state of affairs. Anyone could speak out, both corporations giants and personally any ordinary citizen. It was suggested to answer the question: " Is it necessary to change something (and if so what exactly) in the intellectual property system of Britain so that it promotes innovation and economic growth? "

Then, using these answers, and many other data collected during the study, they compiled their report , where they analyzed in detail the current situation. From this document we find out how things are going with piracy in the United Kingdom.

If you answer in one word: bad. Copyright does not go there, and a number of actions are urgently required, the first of which is to introduce the "Copyright Hub" . It will be not just a register of all works, but a universal worldwide copyright trading system. The first version of the hub should be earned in July 2013.

Call for evidence

But first things first. Back in December 2010, when the document was published , it described in detail what the researchers would like to know. Most of it consisted of questions like " what facts do you have about whether copyright provides the right incentives for authors? ", " What facts do you have about licensing difficulties? ", Etc.

In the allotted time, more than 250 responses were received, not counting those who wished that their opinion was not published. The largest libraries, television and radio companies, associations and unions of authors and copyright holders, such companies as eBay, Google, IBM, Microsoft, representatives of small and medium-sized businesses and individuals responded to the action. Did not fail to speak and the British Pirate Party.

The answers were very different . For example, right holder organizations briefly stated that everything is going fine, it’s just necessary that people begin to respect intellectual property. One student at a law school wrote a whole treatise on the possibilities of electronic commerce in intellectual property. Representatives of e-commerce reported problems:

We believe that the English copyright system prevents people from starting a business in the media field, since it’s hard and you work like a minefield. Some of the best investors leave this area because of the troubles they face.

It is impossible to cover all the diversity of the information received, because only the report itself takes 130 pages, not counting the huge number of accompanying documents, so I will briefly highlight the main points.

The role of intellectual property in economic development

The review begins with a review of what the law should be, and a comparison with reality. I will cite a few quotes:

Intellectual property rights should support economic development by stimulating innovation through a temporary monopoly granted to authors and inventors. Policies must balance economic goals against public as well as the benefits of rights holders against influencing consumers and other interests.

There is no doubt that the point of view of consumers has played a very small role in the definition of British intellectual property policy.

The boundaries between the legal areas of intellectual property laws and the protection of privacy are beginning to blur. In this regard, it is vital that the policy is developed objectively.

Intellectual property rights cannot fulfill their basic economic function (stimulate innovation) if these rights are not respected or their protection costs too much. Ineffective legal regime is worse than no rights at all: they should give confidence and support to business models, but in practice everything went wrong. Widespread disregard for the law destroys confidence, which is supposed to maintain consumer and investor confidence. In the most serious cases, it destroys social solidarity, which allows the law-abiding majority to unite against the criminal minority.

Copyright

In the next chapter, the author proceeds to the consideration of copyright. It is not surprising that most of the data submitted concerned precisely this part of the intellectual property.

It is clear to all that digital technologies are transforming copyright, for the better and for the worse. Violations are ubiquitous; understanding of the law is weak; Millions of works are prohibited for digitization for preservation purposes or are not available at all; The business model of the content industry is under threat, prompting companies to turn to the government, demanding decisive action against consumers and suppliers of “pirated” content.

We have identified certain difficulties in the process of licensing music, both for digital distribution and for alternative uses, such as computer games. Among the respondents who indicated the problems were artists, service providers, and well-known international companies. Complaints include: fragmentation of rights between multiple rights holders, high costs of negotiating conditions, lack of transparency, high advances for access to catalogs, the sad state of the works of artists whose work the publisher decides not to put on the market, closed payment agreements when artists do not know what conditions they will pay.

Examples of the inefficiency of licenses are easy to find. The BBC reported that it took them almost 5 years to settle all the rights needed to launch the popular iPlayer service. Of the group of small technological enterprises that we met at TechHub, half said they had difficulty licensing other people's intellectual property. One such company, which provides online auditions for radio shows and DJ mixes upon request, reported that they had to persuade copyright societies for about 9 months in order to make some progress with licensing. Others said that licensing negotiations are taking place with varying success: some provide access, others refuse without any explanation. Some were even threatened with suing them, instead of discussing business proposals. There were reports that sometimes it is simply impossible to obtain information on what conditions might be, since it is not clear who to contact in order to receive a license.

To solve these difficulties, British scientists propose to introduce the " Digital Copyright Exchange " (Digital Copyright Exchange), first in their own country, and then distribute it to the whole world. This is a database of all materials protected by copyright, plus a mechanism for selling and buying rights. Such a system, according to scientists, will be beneficial to all: the authors, copyright holders and consumers alike. The professor has devoted a considerable part of the work to this question, and considers in detail all the advantages of such an exchange, and the stages of its construction.

Copyright exceptions

An important problem that we have witnessed in recent years is the growing discrepancy between what makes it possible to make exceptions from copyright and reasonable assumptions and the behavior of most people. Digital technologies have made it possible for individuals to use this content as normal, such as sharing music tracks with family members or copying tracks from a CD to play in the car. It’s hard for a person to understand why you can give a friend a book to read, and a digital music file is impossible. The picture is further complicated by the fact that digital content is now sometimes sold with permission to change the format (tracks on iTunes) or “lend” files (Amazon ebooks) at no additional cost.

This causes confusion and creates a disrepute for the law. This discourages consumers and puts the state in a position where it has to “choose” between rightholders and citizens. Effective law enforcement in such circumstances may become impossible.

The copyright law was never thought of as a tool to regulate the development of consumer technology. But that is what it becomes when it starts to prohibit or allow the development or application of such technologies. England can not afford to put unnecessary barriers to innovation.

An example is the message of Martin Brennan, a young British entrepreneur who developed the music player Brennan J7, which stores music CDs on his hard drive, making listening more convenient. The British Advertising Standards Committee ruled (in strict accordance with the law) that the advertisement of this Brennan player must contain a warning that its use leads to copyright infringement.

Martin Brennan writes:

outdated legislation and bureaucracy can sabotage my development. Without exaggerating, I will say that this business costs me more sleepless nights and wasted time than any other in the history of my company. In addition to a legal headache, I still have to persuade buyers that record companies will not sue them. This is not serious, because American companies such as Apple and Microsoft have been selling format-changing products for a dozen years.

Another example is the parody of the song “Empire State of Mind” by Alicia Keys called “Newport State of Mind” (containing a clear allusion to the British intellectual property office, which has its headquarters in Newport). It spawned further parodies, one of which was done by the BBC Comic Relief team. The parody itself is based on the very specific local characteristics of life in Newport, so I do not advise you to look at it, but apparently this is really funny, let's believe the experts and the conclusion that they did:

Legally sound structure would not be mocked by law-abiding in all (except copyright) citizens and organizations of the BBC level.

Piracy and rights protection

I remind you that all the data given in this article relate to the inhabitants of England, and collected by British independent researchers.

A survey published by Consumer Focus in February 2010 showed that 73% of consumers do not know what they are allowed to copy or write. Harris Interactive, an online survey commissioned by BPI, found that 44% of all users of peer-to-peer networks believed that they did not break the law by their actions. The Strategic Advisory Board for Intellectual Property Policy (SABIP) concluded that: “there are good reasons to believe that many people do not perceive software piracy as an ethical problem.”

No wonder consumers are confused. The very concepts of "ownership" and "purchase" are changing. Online music providers (and other publishers) operate on a variety of business models, including: free downloads, paid advertising; free download for small volumes, with payment for more involved or advanced users (the so-called “freemium” model) and various subscription services, including storage, where consumers can compile “their” libraries. It is not always obvious to a casual observer whether the music service is legal - unless of course they decide to raise a flag with a skull and bones on their ships, as Pirate Bay did.

The author of the report indicates that in response to the call to provide the facts, they certainly received many reports of losses. As an example, he cites in particular:

This site “stole” my photos entirely, along with the copyright marks, and used them in high resolution, allowing other “bloggers” to follow the example. Since I took these photos in 2009, I tried to contact several websites and asked them to be removed. With varied success. Some even accused me of violating freedom of expression and threatened to sue. As a result of these violations, I lost the income and trust of my clients.

Given the importance of the problem, one might think that we should have a completely clear picture of the volumes and dynamics of online piracy, but this is not so. There is no doubt that the magnitude of the phenomenon is large, but reliable data are amazingly small. There are no shortages in the claims about the size of violations, but for 4 months of data collection for this review we could not find a single British report whose data would be statistically reliable.

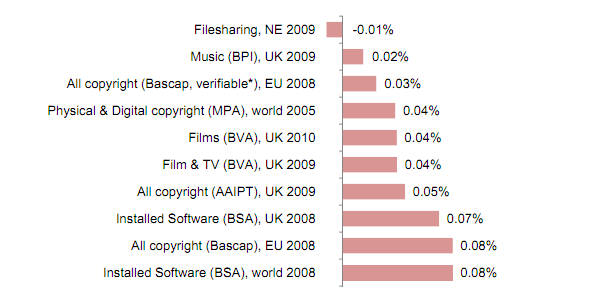

The results of 20 (mostly British) studies of the piracy of music, films, games and software are presented.

The professor notes that measuring any kind of illegal activity presents certain difficulties. But in the case of online copyright infringements there are additional problems. He cites 6 reasons why piracy is more difficult to measure than “ordinary” crimes (of course, it means non-commercial, when users do not receive any money). But among them in the first place is undoubtedly the main reason, I quote:

- violation does not leave physical traces

And the truth is, well, what can you do if a person has criminally downloaded and watched dozens, or even hundreds of films, then erased them, and when they asked him on the street whether he was doing file sharing, he said he did not know what it was.

Most of the experts with whom the reviewers spoke, and the literature they studied, indicate that, despite considerable efforts, it is difficult, if not impossible, to measure the total impact (gain and loss) of piracy on the economy as a whole.

Nevertheless, even if you count the losses from copyright infringement under the worst scenario (according to the media industry itself), they account for less than 0.1% of all economic activity both in the United Kingdom and in Europe and the world as a whole.

There are other questions that we would like to find answers to: how bad is the situation in England compared to other countries? What is the trend? Is online piracy growing or decreasing? We simply could not give an answer with any accuracy.

Further, the author proceeds to the analysis of methods to combat piracy. As such measures, as well as all over the world, toughening of punishments and propaganda campaigns are used. He notes that despite the very large number of these campaigns (the researchers counted 333), few people analyzed their results. Nevertheless, it seems that the level of piracy, especially in developing economies, has remained just as high, and that consumer attitudes towards piracy have remained ambivalent.

Available evidence indicates that it is not laws and propaganda that are more successful in the fight against piracy, but the emergence of new business models. The results of the Harris Interactive survey, which was conducted in 2010 for BPI Digital Music Nation, are interesting. The respondents were asked why they stopped using peer-to-peer networks.

- 29% - more convenient paid service appeared

- 24% - it was dishonest in relation to performers and authors

- 23% - began to use free online services

- 21% - now listen to music in social networks

- 16% use forums or blogs

- 13% - that they have already downloaded almost everything they wanted

- 12% - began to fear that they will be caught

- 12% - realized that using illegal sources is not good

The professor summarizes the chapter on piracy as follows:

Some rightholders say that “it’s impossible to compete with free”. If (and research shows that most likely it will be so) even more stringent measures will be powerless to have a significant impact on piracy, competition with free will become an integral feature of the digital business.

Other topics

Separate chapters of the review are devoted respectively to the effect of intellectual property laws in the international context, areas of patent law and design. I will not review these chapters here. I will dwell only on one last point.

The professor notes that legal disputes in the field of intellectual property were of such scope that the fees of lawyers involved in this became available only to giant corporations.

Judicial costs can be overwhelming, especially for small firms. In a simple case involving patent infringement, a company can expect costs of around £ 750,000, which largely depends on who is acting on the other side.

A claim for copyright infringement of just £ 2,000 can result in legal costs of about 20-30 thousand, which is why people refuse to protect their intellectual property.

Conclusion

In the last chapter, the author concludes that we must definitely change course. He describes and justifies all his recommendations in the most detailed way, but I only have to list them very briefly:

- introduce “Digital Copyright Exchange”;

- to work out exceptions from copyright;

- change the patent system so that it does not slow down innovation;

- protect the rights of small businesses;

- reform management structures.

Despite the fact that the professor was trying very hard to withstand the entire document in the official style, in the final chapter there are obvious notes of irritation:

History shows that making changes to the English intellectual property system is at best like patching holes. In the 70s, The Banks Review complained about the lack of evidence that underpins politics. Thirty years later, the 2006 Gowers Review pointed to the same thing. Our departmental system seems incapable of effectively pursuing a policy based on facts. With the increasing pressure of technology on the copyright system, this inability to adapt organically resulted in a tumultuous stream of reviews: the Creative Economy Program in 2007, the Digital Britain Review in 2008-09, and the Government's Copyright Strategy in 2009. And now this review. Despite all this activity, many, if not most of the recommendations for change, remain gathering dust in a box marked “too difficult.”

It is impossible to avoid the conclusion that the policy of England in relation to intellectual property over the past few years remains deeply wrong. All of the above makes sense only after the situation in this area is improved. The fact is that in this field there are strong divergent interests and one of the most skillful and influential lobbyists on the British political scene. The most striking example of a lobbying problem is the continuous extension of copyright terms.

Reaction to the report

What did the English government do? In September 2011, 4 months after the Hargreaves report lay down on the table, they began to force an increase in the term at the European Council of Ministers, and secured its adoption.

But it is not all that bad. It turned out that they also listen to the opinion of British scientists! The first recommendation on the list was the creation of a digital copyright exchange. In November 2012, the government was appointed responsible for exploring the possibility of developing such a system. In July 2012, he published a report recommending the creation of a British copyright hub. In March 2013, the government allocated £ 150,000 to finance it.

Preliminary information and frequently asked questions can now be read on the website of the hub . The first valid version is due in July and will include:

- register of works, rights and licenses;

- a digital exchange that allows you to sell and buy licenses online;

- search the database to determine the work - orphans;

- copyright information portal.

It is assumed that participation in the hub will first be voluntary (12 organizations have already been announced). Then steps will be taken to force all other English rightholders to join. And then the expansion of the system to the whole world is planned.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/182902/

All Articles