Usability Testing. Perfect Moderator - Sophisticated Innocence

The most informative, time-consuming and interesting type of research that is conducted to study the usability of the interface - is testing "on", or better to say "with" users. Its main task is to provide an opportunity for all interested parties to see how a person uses the product and what difficulties it faces when interacting with it.

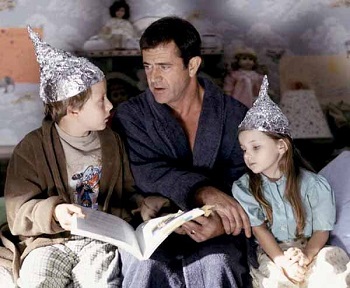

The most informative, time-consuming and interesting type of research that is conducted to study the usability of the interface - is testing "on", or better to say "with" users. Its main task is to provide an opportunity for all interested parties to see how a person uses the product and what difficulties it faces when interacting with it.After that, some unprepared viewers begin to look at their offspring in a new way and stop wondering why no one wants to use them (however, this effect is not always lasting for a long time, so it is recommended to take this “pill” regularly). Another thing moderator - the sophisticated viewer of user drama.

In the classical sense, a moderator is a person who exclusively conducts sessions. Its main task is to create such testing conditions so that a person feels comfortable, forgot that he is sitting in a stranger room with a stranger, and interacting with the interface in the way he used to do it in real life. Monitoring the respondent and fixing the difficulties that arise during his work with the product are handled by the observer (in the foreign manner, “laptop”). In the ideal case, the moderator has a minimal understanding of the design of the study and the specifics of the product, which allows it to be as unbiased as possible.

')

In actual practice, everything is different. A moderator is often a “full cycle” researcher involved in all stages of usability testing.

The first and, perhaps, the most important of these stages is the preparatory one. Before conducting a study, we try to carefully examine the product to identify all kinds of pitfalls that we may encounter in the process of testing with users. We talk with the customer and actively “test” the product from different sides.

From the very beginning of my work as an analyst, I wondered how well, as a moderator, I need to know the interface that we are going to test on users. It seems obvious that in order to prepare test scripts and compile a list of questions for respondents, we must be well versed in the interface. In addition, it seems that we must be ready to anticipate all the difficulties that the user may encounter during testing, so that in case of an insurmountable obstacle, take him to the right path, which we have planned.

I hope you caught a touch of doubt in my words? So, I propose to call into question the obvious thing: "The moderator must thoroughly know the interface, the testing of which he conducts ."

Usability is not a user's attorney

Being a usability consulting company, most often we are not the creators of products that we test (we would be happy to help not only with words, but with deeds, and the customer is not always ready to provide such an “access to the body” of his project). For this reason, we obviously know the product worse than our customers, who are either owners of a business whose goals are served by the interface, or contractors involved in the development or promotion of the interface.

And this is one of the reasons why people contact us. We can look at the product from the side - through the eyes of the user, and at the same time we either imitate user behavior ourselves (peer review), or monitor actual users (usability testing). Our view is not yet clear. We did not spend days and nights for endless redrawing the interface; we will never receive money from advertising banners placed in it; we did not spend hours in meetings at which unsuccessful attempts were made to reconcile the multidirectional parties, always present within the company. We have not suffered yet. We have no emotional attachment to the product as a whole, or to individual solutions in its interface.

In this regard, before the start of the project, we are neither on the side of developers, since we are not related to product development, or on the side of users, because we are not the “users” of the interface under test. The question is, on whose side should we stand as researchers. And the answer is very simple: no matter what, or if you like, stay on your own.

Motivation determines experience

As a rule, any interface or product is tested on two “global” user groups: experienced and inexperienced. Experienced users are those who have already encountered this or a similar product when solving their problems. Beginners are, as a rule, users who have not yet had experience interacting with the interface, but are potentially interested in this. For example, they are currently performing similar actions offline, but this is a dreary and uninteresting task for them that can be simplified with the participation of technology.

In preparation for testing, we gain experience with the application, as if approaching in this regard to the group of “experienced” respondents.

It seems intuitively that this is so, but let us also question it. As I mentioned, more often than not, we are not users of the product that we are testing. In simple words, we have no real motivation to use it, our motivation, if you like, is conducting research — by studying a product before conducting research, we consciously or unconsciously look for flaws in it (and find). This differs from the behavior of the “average” user who would like to ignore problems.

When an elephant is actually a fly

What is the danger here? The moderator is also a person, which means that he has unconscious and unconscious impulses with which he is not always able to cope. For example, knowing that the application does not correspond to the generally accepted heuristics and, expecting that this will lead to problems in working with it, it can unwittingly during the testing session push the user to recognize this fact. This will result in a hypertrophic view of the problem, which is of critical importance only in the moderator's mind, but not a real obstacle to the work of users.

I emphasize that this is not a far-fetched problem, but a real one. Simply, each problem has its own degree of criticality - that is, it blocks the work of users, are they ready to stop using the application or will be quite successful in continuing to work with it no matter what.

The simplest example that lies on the surface is social networks. Some may disagree, but I dare to say: the interface of the social networking site Facebook is far from what we would call “intuitive”. The “entry” stage is not easy for a beginner, so for a long time he uses only the most basic functions. But all this does not matter. Nothing can prevent a user from using a social network if his friends are there (as it is sung in the well-known children's song: “I have snow, I feel hot, and it is pouring rain when my friends are with me!”). Ultimately, users become accustomed to the logic proposed by them, and the so-called interface “improvements” can, on the contrary, be perceived negatively.

God forbid someone thinks that this way it is possible to “bypass” usability by making any service successful only by incorporating the social aspect. This is not about this or not about this. Every usabilityist is familiar with the phrase (it’s also the name of the book) “Don't make me think.” I have one more sentence: “Do not think for users!”. It seems that now no one will think, but no. If we slightly modify the phrase of Steve Krug, then it will become almost synonymous with my version: “Do not make users think like you.”

Knowledge - strength or weakness?

I don’t want to say to all of them that studying the interface moderator before testing is a useless and even harmful exercise. The collection of data on the product being tested and the development of the research design is a very important step, on which the relevance of the results obtained depends.

Concluding the article, I would like to mention those moments that researchers should pay attention to before usability testing:

- Studying the product for subsequent testing on users it is important for us to find out how people use it, and not to seek and find confirmation of their own convictions.

- Formulate tasks for testing in the freest way possible - do not restrain users, let them freely work with the interface, let them forget about your presence. Better yet, let them formulate the tasks themselves. Pre-test interview often gives such an opportunity.

- Different products require a different degree of immersion moderator in the subject: if we test a mass product - the moderator does not necessarily have their own opinion about the product, if you have it - better keep it with you.

- For each rule there are exceptions, each interface requires its own approach. For example, when testing a game interface, it is very desirable that the moderator has a clear idea about him and himself was a player, otherwise it will be very difficult for him to understand what is happening on the test and turn on empathy.

- Two heads are always better than one - do not forget to let your colleague read your script, it always gives more guarantees of impartiality.

That's all for today. Thanks for attention!

Author: Ekaterina Kaminska, UIDG analyst.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/182384/

All Articles