Difficulties of translation or how not to do software localization

The idea of this small article was born when I told the Milfgard habrauser a couple of life stories about my experience in performing both translations and working with translation results. He offered to share them with the community, which I actually do. I hope the information will at least seem interesting and, perhaps, reveal the secrets of the origin of some translations.

When I was a student, I worked as a freelance translator at one of the translation bureaus in Moscow. I mainly dealt with translations on the subject of my education, that is, I translated everything related to the communications and telecommunications industry. They paid little by market standards, but as a student it suited me then.

All the work of the translation agency was to collect as many orders as possible, and then distribute it among several translators. In fact, some kind of crowdsourcing was obtained. The main object of linguistic bullying became documentation for software or hardware. The most vivid examples in my memory were the translation of the Huawei SDH / PDH documentation and the translation of the documentation on the Comverse platform. I truly feel sorry for the employees of the customer companies, and now I will tell you why.

Received a translation bureau, for example, an order to translate 1000 pages from English into Russian documentation for any software or hardware. Further, this amount of work was distributed depending on the workload of specific translators (and depending on their average speed of translation), somewhere among 10–20 people. Then there was a meeting at which a translator of terms was distributed to translators in order to exclude cases of different translations of established terms and / or expressions.

This strategy had a definite plus - the work of the corrector is much easier when 20 people do not translate the same word differently. However, in order for all this to work as it should, it was necessary to fulfill two simplest conditions:

And what happened in practice? In practice, the first condition was immediately violated. The comrades used a glossary from the Russian-language version of the book Cisco Press about the basics of building networks as a glossary of terms. A wonderful book for beginners. Only she had one drawback. I think you already guess what. That's right - she had a terrible translation into Russian. The glossary by the number of erroneous translation by one page exceeded all other books of this publisher, released at that time. Now, when I write the lines, I have a sneaking thought that this book itself was translated by the same crowdsourcing method that I describe. This kind of recursion with deep negative feedback in the context of translation quality.

The second condition was also violated, but in view of the human factor. Translators were divided into those who simply ignored the glossary of terms (without justifying their actions at all), and those who understood the full horror of mistakes in this dictionary and still preferred to make a high-quality translation. I have repeatedly pointed out to my colleagues in the shop about errors in their vocabulary, but the forty-year-old foreheads were not inclined to believe a twenty-year-old student.

As soon as the translation of the parts of the documentation was ready, the editor-corrector collected all this together. He was paid even less (for not for the number of characters, but for time, and all the time they were driven), so the quality of the final text was in most cases terrible. Once I myself worked as a proofreader and committed myself to do more after a day of work, because in half of the cases I had to take the original and translate the text completely anew.

The only faint ray of light in the dark realm of the terrible translation machine was the editor-in-chief of this bureau. He himself did not translate anything on the subject of telecommunications (and this is for the better), however, he always repeated that they needed specialists in a particular industry with knowledge of the language, and not ordinary people who graduated from the translation department. Alas, not all specialists knew equally well not that English, but also Russian. As shown further communication with them, not all experts turned out to be specialists.

')

My further life and professional experience only confirmed this simple truth. A technical translator is not a translator who has a technical vocabulary at hand, he is a technical specialist who is well versed in his technical field and at the same time fluent in English (or some other) language.

Back in 2004, I moved away from technical support for Cisco equipment and solutions built on it, and switched to network monitoring tasks. So I first became acquainted with the Micromuse Netcool software products, which in 2006 became part of the IBM Tivoli software line. My current employer is an active user, so to speak, of the Fault and Perfomance Management systems from IBM, so for almost four years now I have been actively involved in closed beta tests of the software we have.

At a certain point, by releasing a new version of the web portal of the Netcool / Omnibus WebGUI monitoring system, IBM decided that the portal should be localized. About the fact that the language preference of the user, they determine only through the USER_AGENT browser, I will not tell much. This theme is worth a separate song with swear words.

How IBM completed the translation is a very good example of how not to localize. In the process of beta testing, it turned out that employees of the Russian division of IBM were responsible for the translation into Russian. They even had a software project manager with a PhD degree there. True, based on what turned out to be in the final product, the impression was created that the Russian division of IBM used the services of the cheapest translation agency in Moscow, and they in turn hired the most illiterate translators.

I don’t make all the translation shoals, I think it makes no sense It is unlikely that it will be interesting to read a dozen pages. I will cite as examples only the brightest moments.

We are all used to the fact that the View menu item translates as “View”. IBM decided otherwise and translated it as “Views”. Because of this, the section of the portal View Membership was translated as "Membership in views". It must be said here that the translation of the last phrase even for those who know the context is rather complicated. On the one hand, the View in the application menu is “View”, on the other hand, the portal section refers to the management of entities called View and determines which components of the page will be elements of this entity. Therefore, the most logical translation would be "Elements of representations." This is one of those cases in a technical translation when a literary translation is better than a literal one.

I even conducted an experiment by showing a section of the portal in Russian to my colleagues working with this software. None of them understood what they were talking about, although with the English version of the portal they work fine to this day.

You can argue for a long time about which language is richer - Russian or English. I am not a philologist or even a linguist, so I don’t know the correct answer to this question. However, I often come across situations where a simple combination of English words each translates into Russian in different ways. There is an applet / application called Active Event List in Netcool / Omnibus. One name causes problems with translation, not only in Russian, but also in German, the knowledge of which allowed me to compare with the German localization.

Not only I, but also German users during the beta test noticed that the interpretation may be twofold. "List of active events" or "active list of events" - both options are, in fact, misleading.

"List of active events" implies that there are inactive events. And where are they, and where is their list? (The correct answer is in another IBM historical product reporting software). An event in its essence ceases to be active (current) only when it is removed from the system, that is, when the problem that caused it has been resolved.

“Active list of events” - it’s hard to understand what can be invested in such a translation option, except for the fact that events in the list can dynamically change. However, they do this in other ideas, which makes such a differentiation incorrect, and again, calling the event list interactive (which is closer to the truth) can only confuse users.

I suggested to my IBM colleagues that I simply rename the Active Event List in the Russian localization to the “Event List”. Alas, this is one of the few changes that they did not end up with, leaving the “List of active events” option.

In general, a small linguistic bomb was originally laid in the software. Since we are talking about a passive monitoring system that receives various informational messages about various conditions and problems from equipment, the system has historically managed to use as many as three words to denote such messages - Event, Alert and Alarm. If Event can be safely translated as an “event,” then Alert / Alarm is already an “accident.” Linguistically, Alert is considered to be an “accident”, perhaps not entirely true, but a more correct version of the “notice” may confuse the Russian-speaking user even more.

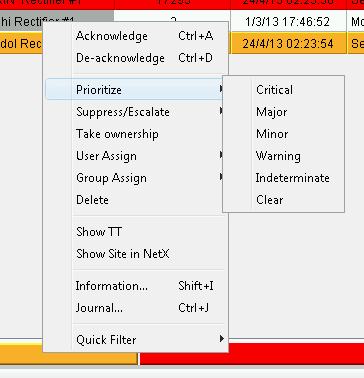

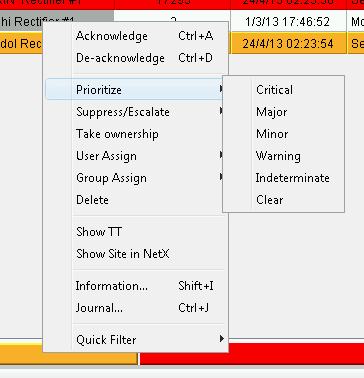

In Netcool / Omnibus, the concept of a “severity level of an accident” (Severity level) with possible values of Clear, Indeterminate, Warning, Minor, Major and Critical. There is actually a section of the context menu, where this degree can be changed manually. Not to be unsubstantiated, I’ll give a screenshot of what it looks like in the English version of the software:

The words are all obvious, but they had to translate everything, so they were also translated. As a result, these six meanings were translated by different parts of speech: somewhere in the noun, somewhere in the adjective, the word Clear in general got the verb. He was translated as “clear” (which is wrong in the concept of software, because it’s not an action, but I never came up with the correct version of the adjective or noun).

Unfortunately, in Russian, words have a gender, and adjectives tend towards gender. I don’t know why, in the first version of the localization of this software, the menu item was called “Increase Priority” (although the menu allows it to be reduced), but the values of this priority in those places where adjectives were used turned out to be feminine. Neither the word “priority” nor the word “event” belong to the female gender. Only the word “accident” belongs to it, but here's the bad luck - the word “accident” was not used anywhere in the system interface.

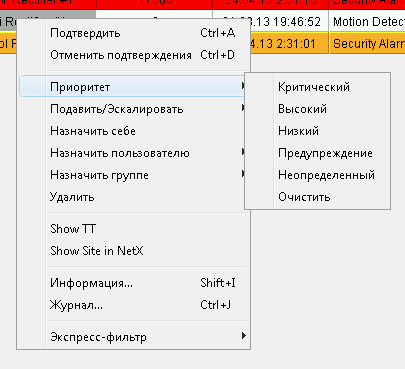

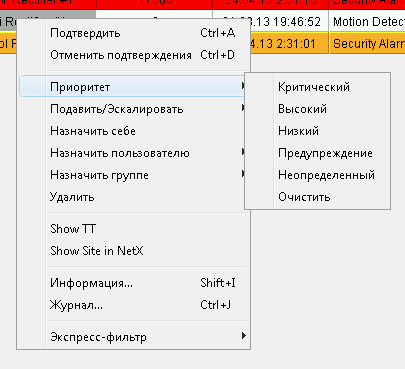

During the beta test, we had to write back to IBMers a translation from Russian to English with detailed linguistic comments. They were a bit crazy about this “quality”, but in the end they sent my comments to the Russian division, where I was redirected to the same comrade with a degree who was responsible for localization. He did not particularly want to admit mistakes, but he very thoroughly asked me for the right translation options. I was not sorry, and I provided it, after which, in fact, I was sent almost to FIG. I even did not say "thank you". However, my efforts were not in vain, and now the menu looks like this:

By the way, in the first version of localization, the Suppress / Escalate item was somehow translated as “Suppress / Expand”. My colleagues and I laughed for a long time what they propose to expand, and why the word Suppress was not translated as “Narrow”. So at least it became symmetrically wrong.

Or rather, even two.

Software localization cannot be trusted to people who do not understand how this software works and what it does. Even if the translation is done by professional translators (which sometimes is no longer good), there must always be technical specialists who are ready to correct all the shortcomings.

After this story, I stopped writing to my Russian comrades at IBM, and as part of each new beta of software, I immediately send my American and English colleagues a collection of translation jambs. Small efforts from year to year localization is getting better.

Experience shows that it is much easier for people to memorize English terms once and introduce, say, Russianized variants into use, than to understand what the translators have done there. In the context of the above-mentioned software, everyone understands something like “clear-crash”, “conjure”, “poklit”, etc. Recently, I read for colleagues from the CIS training in Armenia. Only at the end of the fifth day of the training I was told that “clear” in Armenian is, forgive, the most indecent version of the designation of the male sexual organ.

PS: I would love to add a topic to the hub "Translations", but alas, there is not enough of what is impossible to say here.

UPD: Thank you! Already enough, added to the hub "Transfers."

A bit of background

When I was a student, I worked as a freelance translator at one of the translation bureaus in Moscow. I mainly dealt with translations on the subject of my education, that is, I translated everything related to the communications and telecommunications industry. They paid little by market standards, but as a student it suited me then.

All the work of the translation agency was to collect as many orders as possible, and then distribute it among several translators. In fact, some kind of crowdsourcing was obtained. The main object of linguistic bullying became documentation for software or hardware. The most vivid examples in my memory were the translation of the Huawei SDH / PDH documentation and the translation of the documentation on the Comverse platform. I truly feel sorry for the employees of the customer companies, and now I will tell you why.

Received a translation bureau, for example, an order to translate 1000 pages from English into Russian documentation for any software or hardware. Further, this amount of work was distributed depending on the workload of specific translators (and depending on their average speed of translation), somewhere among 10–20 people. Then there was a meeting at which a translator of terms was distributed to translators in order to exclude cases of different translations of established terms and / or expressions.

This strategy had a definite plus - the work of the corrector is much easier when 20 people do not translate the same word differently. However, in order for all this to work as it should, it was necessary to fulfill two simplest conditions:

- The glossary must contain correct translations of these same terms;

- translators should use it.

And what happened in practice? In practice, the first condition was immediately violated. The comrades used a glossary from the Russian-language version of the book Cisco Press about the basics of building networks as a glossary of terms. A wonderful book for beginners. Only she had one drawback. I think you already guess what. That's right - she had a terrible translation into Russian. The glossary by the number of erroneous translation by one page exceeded all other books of this publisher, released at that time. Now, when I write the lines, I have a sneaking thought that this book itself was translated by the same crowdsourcing method that I describe. This kind of recursion with deep negative feedback in the context of translation quality.

The second condition was also violated, but in view of the human factor. Translators were divided into those who simply ignored the glossary of terms (without justifying their actions at all), and those who understood the full horror of mistakes in this dictionary and still preferred to make a high-quality translation. I have repeatedly pointed out to my colleagues in the shop about errors in their vocabulary, but the forty-year-old foreheads were not inclined to believe a twenty-year-old student.

As soon as the translation of the parts of the documentation was ready, the editor-corrector collected all this together. He was paid even less (for not for the number of characters, but for time, and all the time they were driven), so the quality of the final text was in most cases terrible. Once I myself worked as a proofreader and committed myself to do more after a day of work, because in half of the cases I had to take the original and translate the text completely anew.

The only faint ray of light in the dark realm of the terrible translation machine was the editor-in-chief of this bureau. He himself did not translate anything on the subject of telecommunications (and this is for the better), however, he always repeated that they needed specialists in a particular industry with knowledge of the language, and not ordinary people who graduated from the translation department. Alas, not all specialists knew equally well not that English, but also Russian. As shown further communication with them, not all experts turned out to be specialists.

')

My further life and professional experience only confirmed this simple truth. A technical translator is not a translator who has a technical vocabulary at hand, he is a technical specialist who is well versed in his technical field and at the same time fluent in English (or some other) language.

IBM is great and terrible

Back in 2004, I moved away from technical support for Cisco equipment and solutions built on it, and switched to network monitoring tasks. So I first became acquainted with the Micromuse Netcool software products, which in 2006 became part of the IBM Tivoli software line. My current employer is an active user, so to speak, of the Fault and Perfomance Management systems from IBM, so for almost four years now I have been actively involved in closed beta tests of the software we have.

At a certain point, by releasing a new version of the web portal of the Netcool / Omnibus WebGUI monitoring system, IBM decided that the portal should be localized. About the fact that the language preference of the user, they determine only through the USER_AGENT browser, I will not tell much. This theme is worth a separate song with swear words.

How IBM completed the translation is a very good example of how not to localize. In the process of beta testing, it turned out that employees of the Russian division of IBM were responsible for the translation into Russian. They even had a software project manager with a PhD degree there. True, based on what turned out to be in the final product, the impression was created that the Russian division of IBM used the services of the cheapest translation agency in Moscow, and they in turn hired the most illiterate translators.

I don’t make all the translation shoals, I think it makes no sense It is unlikely that it will be interesting to read a dozen pages. I will cite as examples only the brightest moments.

Types and Memberships

We are all used to the fact that the View menu item translates as “View”. IBM decided otherwise and translated it as “Views”. Because of this, the section of the portal View Membership was translated as "Membership in views". It must be said here that the translation of the last phrase even for those who know the context is rather complicated. On the one hand, the View in the application menu is “View”, on the other hand, the portal section refers to the management of entities called View and determines which components of the page will be elements of this entity. Therefore, the most logical translation would be "Elements of representations." This is one of those cases in a technical translation when a literary translation is better than a literal one.

I even conducted an experiment by showing a section of the portal in Russian to my colleagues working with this software. None of them understood what they were talking about, although with the English version of the portal they work fine to this day.

Language richness

You can argue for a long time about which language is richer - Russian or English. I am not a philologist or even a linguist, so I don’t know the correct answer to this question. However, I often come across situations where a simple combination of English words each translates into Russian in different ways. There is an applet / application called Active Event List in Netcool / Omnibus. One name causes problems with translation, not only in Russian, but also in German, the knowledge of which allowed me to compare with the German localization.

Not only I, but also German users during the beta test noticed that the interpretation may be twofold. "List of active events" or "active list of events" - both options are, in fact, misleading.

"List of active events" implies that there are inactive events. And where are they, and where is their list? (The correct answer is in another IBM historical product reporting software). An event in its essence ceases to be active (current) only when it is removed from the system, that is, when the problem that caused it has been resolved.

“Active list of events” - it’s hard to understand what can be invested in such a translation option, except for the fact that events in the list can dynamically change. However, they do this in other ideas, which makes such a differentiation incorrect, and again, calling the event list interactive (which is closer to the truth) can only confuse users.

I suggested to my IBM colleagues that I simply rename the Active Event List in the Russian localization to the “Event List”. Alas, this is one of the few changes that they did not end up with, leaving the “List of active events” option.

In general, a small linguistic bomb was originally laid in the software. Since we are talking about a passive monitoring system that receives various informational messages about various conditions and problems from equipment, the system has historically managed to use as many as three words to denote such messages - Event, Alert and Alarm. If Event can be safely translated as an “event,” then Alert / Alarm is already an “accident.” Linguistically, Alert is considered to be an “accident”, perhaps not entirely true, but a more correct version of the “notice” may confuse the Russian-speaking user even more.

Degree of criticality

In Netcool / Omnibus, the concept of a “severity level of an accident” (Severity level) with possible values of Clear, Indeterminate, Warning, Minor, Major and Critical. There is actually a section of the context menu, where this degree can be changed manually. Not to be unsubstantiated, I’ll give a screenshot of what it looks like in the English version of the software:

The words are all obvious, but they had to translate everything, so they were also translated. As a result, these six meanings were translated by different parts of speech: somewhere in the noun, somewhere in the adjective, the word Clear in general got the verb. He was translated as “clear” (which is wrong in the concept of software, because it’s not an action, but I never came up with the correct version of the adjective or noun).

Unfortunately, in Russian, words have a gender, and adjectives tend towards gender. I don’t know why, in the first version of the localization of this software, the menu item was called “Increase Priority” (although the menu allows it to be reduced), but the values of this priority in those places where adjectives were used turned out to be feminine. Neither the word “priority” nor the word “event” belong to the female gender. Only the word “accident” belongs to it, but here's the bad luck - the word “accident” was not used anywhere in the system interface.

During the beta test, we had to write back to IBMers a translation from Russian to English with detailed linguistic comments. They were a bit crazy about this “quality”, but in the end they sent my comments to the Russian division, where I was redirected to the same comrade with a degree who was responsible for localization. He did not particularly want to admit mistakes, but he very thoroughly asked me for the right translation options. I was not sorry, and I provided it, after which, in fact, I was sent almost to FIG. I even did not say "thank you". However, my efforts were not in vain, and now the menu looks like this:

By the way, in the first version of localization, the Suppress / Escalate item was somehow translated as “Suppress / Expand”. My colleagues and I laughed for a long time what they propose to expand, and why the word Suppress was not translated as “Narrow”. So at least it became symmetrically wrong.

Little such morality

Or rather, even two.

Software localization cannot be trusted to people who do not understand how this software works and what it does. Even if the translation is done by professional translators (which sometimes is no longer good), there must always be technical specialists who are ready to correct all the shortcomings.

After this story, I stopped writing to my Russian comrades at IBM, and as part of each new beta of software, I immediately send my American and English colleagues a collection of translation jambs. Small efforts from year to year localization is getting better.

Curiosities of using English words

Experience shows that it is much easier for people to memorize English terms once and introduce, say, Russianized variants into use, than to understand what the translators have done there. In the context of the above-mentioned software, everyone understands something like “clear-crash”, “conjure”, “poklit”, etc. Recently, I read for colleagues from the CIS training in Armenia. Only at the end of the fifth day of the training I was told that “clear” in Armenian is, forgive, the most indecent version of the designation of the male sexual organ.

UPD: Thank you! Already enough, added to the hub "Transfers."

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/177741/

All Articles