Don Jones "Creating a unified IT monitoring system in your environment." Chapter 5. Turning problems into solutions

In this chapter, the author is going to share his vision on how to store and keep up to date the knowledge accumulated as a result of a long walk on a rake. The main difficulty in storing and maintaining an array of knowledge is to find people who would combine the incompatible: they were careful, creative, diligent, had a sharp analytical mind, intuition

Content

Chapter 1. Managing your IT environment: four things you do wrong

Chapter 2. Elimination of management practices for individual sites in IT management

Chapter 3. We combine everything into a single IT management cycle

Chapter 4. Monitoring: a look beyond the data center

Chapter 5: Turning Problems into Solutions

Chapter 6: Unified Case Management

')

Chapter 5: Turning Problems into Solutions

A satirical magazine, The Onion, recently published an economic story. In it, it was described as a special kind of scientist, called a historian , promoted an original idea of looking at the past . “Sometimes,” said one pseudo-historian, “we can look at how people tried to solve problems like the ones we have today. We can study and understand how their solutions worked then, and this can give us an idea of whether this solution will work with us. ” Ha!

Although this applied more to politicians who continue to make the same mistakes over and over again, The Onion barks apply to IT. “Look, if our problem happened three months ago, and we solved it then, perhaps, we will be able to solve it much faster if it suddenly appears now. And what, by the way, did we do last time? Maybe if we do everything the same, then there will be the same result as then? ”.

In other words: Perhaps you have children, or at least you know those who have them. Have you ever told a child not to touch a hot pot standing on the stove? Of course. Did they touch her? Of course. How many times? Usually only one. This is because the training of human beings is primarily based on the mistakes they make. We remembered the mistake, and the fact that we understood how to avoid it or resolve the consequences of what happened, gives us confidence that we can do it quickly in the future. Memory becomes a key factor, and as we get older, we stop reaching out to hot pots and start playing with our computers at work, and here it becomes harder for us to remember. This chapter is devoted to the last aspect of unified management: analyzing a solved problem and turning it into solutions for future use.

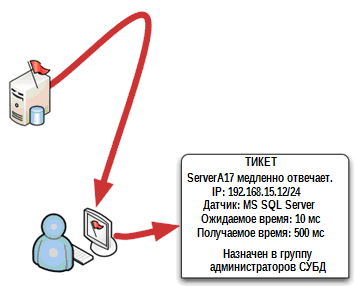

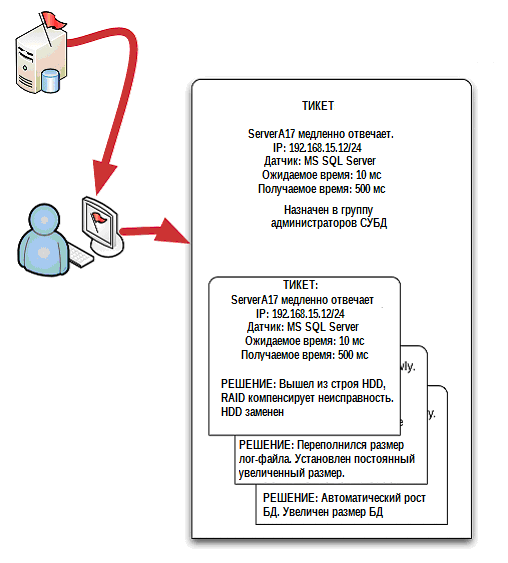

We close the cycle: we connect the service desk with monitoring

Before we dive into such an aspect of problem solving as memory, we must first close the operational cycle in our set of tools for unified monitoring. Earlier in this book, we discussed that one of the aspects of a unified monitoring system is the ability to monitor the status of devices and services, such as, for example, a DBMS server. When a problem state is registered, the monitoring system creates an alarm message, usually displayed on the console, and notifies someone else via e-mail or SMS. A truly unified system can also create a problem ticket ticket tracking system. The ticket allows the management to see the status of the problem and how long it exists, the system also allows the ticket to switch between different employees working on a joint solution to the problem. The ticket can be automatically filled with information related to the problem, helping the employee to solve it faster. In fig. 5.1 shows this first step: An alarm message is displayed on the console, and a ticket is generated from it.

Figure 5.1: Receiving an alarm message and opening a ticket.

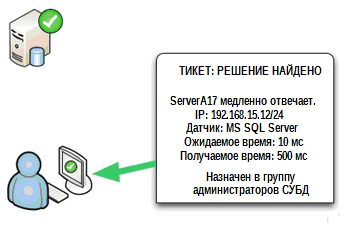

We hope that in the end, the problem will be solved. Usually, by this time, the specialist who has completed work on the ticket closes it and makes a special mark about it.

And what about our alert - alarm message?

Of course, that part of the monitoring system that deals with tracking in real time will understand that the problem no longer exists, but this does not at all mean that the alarm message will disappear.

Usually, you need the alerts to be kept until the problem is resolved, up to its complete correction, which means that when you close the ticket, you need to somehow reset the alarm message.

Such a problem is very often encountered among organizations that do not have a unified monitoring system: close the ticket in one system, then enter the monitoring system and mark that the alert has been processed. However, in a fully unified system, it is usually arranged that the closure of a ticket also resets the original alarm message. Figure 5.2 shows how this cycle closes within a single system.

Figure 5.2: Closing a ticket resets the original alert.

There is a reasonably good reason to separate alerts and tickets between each other.

Ticket is subject to internal use. It contains technical information designed to solve problems and notifications about the process of working on a situation. The alarm message, however, is suitable for use by a wider group of people. Alert can be used in a large number of indicators used in the company. For example, to demonstrate to users that this system is currently not working properly. It is not necessary to reset the Alert, because the monitoring system no longer sees the wrong indicators, but temporary relief from the situation does not at all mean that it has been resolved . You may want the alert to remain in place, as a high-level indicator, such as the fact that “we know that now there is not everything is in order,” but at some point you still need to reset it and return the external signs of the system to “ works fine". If this is done automatically as part of closing a ticket, then this may be a convenient way to notify two different audiences of users.

Preserved knowledge means faster resolution of problems in the future.

After the problem is solved, the information about it has not disappeared anywhere. At least you hope so. As I said at the beginning of this chapter, each problem solved is a potential accelerated resolution of problems in the future - just as if you meet exactly the same, or just the same. In other words, you need to save information about the problem and the method of solving it for future use.

Knowledge base

Probably the oldest way to save information is the knowledge base (BR).

Once, at the very beginning, these were separate databases consisting of articles describing where to look for a way out in a given situation. If you have a problem, you first do a search in the knowledge base, checking if there are any hints at solving the problems.

One of the earliest knowledge bases that became widespread was Microsoft Knowledge Base, delivered on a CD in the early 1990s. Today, it is a large collection of online articles - so large that the knowledge base has a separate article on how to properly query it (shown in Figure 5.3, if you suddenly did not believe me).

Figure 5.3: An article from the Microsoft Knowledge Base.

This shows us one problem with knowledge bases: people need to learn to work with them and we must constantly remember how to do it. Unfortunately, IT professionals do not necessarily belong to the audience, for which in most cases you need to get a manual (or knowledge base) if an incident is somewhere on the horizon.

Most likely, they will immerse themselves in the study of what happened and try to use their own skills to solve the problem. Using the knowledge base, in simple terms, “search for KB,” usually happens after internal knowledge has been exhausted. Part of this situation arises because of internal professional competence, partly because of the poor use of most knowledge bases, and partly because knowledge bases become outdated very quickly.

This indicates another serious problem: the need to keep knowledge bases up to date. Exactly as long as you carefully place the tags on the articles - which product versions the solution belongs to and so on, your articles are useful, otherwise they become a source of misinformation . Consider a version of a business application, for example, version 1.5, which has a specific problem. You document this in the article BZ, then you rely on its content after the problem occurs again. As a result, your developers fix the bug in version 1.6. Has anyone bothered to go back and fix the article in the BR? Not. Even if the article states that it is applicable to version 1.5, there is no more useful information in it. Has the problem been fixed in 1.6? Will the repair procedure work in 1.5? If you are using 1.6. and the problem arises again, should you follow the procedure specified in 1.5 or report it as a new problem - because the developers decided that everything was fixed and was working as it should?

All these assumptions are based on the fact that you understand the main problem of knowledge bases: the timely placement of articles in it. Vendors such as Microsoft spend millions of dollars a year on the salaries of people who are no more than writing documentation and writing articles for knowledge bases. There is a desire to do this kind of investment? I saw a lot of companies that had created knowledge bases that were used with enthusiasm for several months, then work with them began to slip and, in the end, their use was reduced to nothing.

Tickets as knowledge base articles

The first solution to many problems inherent in knowledge bases is to stop using a separate KB for these tasks and use closed tickets as a knowledge repository. Basically, all modern ticket tracking systems today have this feature. This approach solves the global problem of BZ: the initial filling of content, since tickets are already content. A good ticket handling system will also help answer the “what’s what” question, because your tickets are usually distributed over specific products or services. And if you are reading an old ticket, then at least you know what product or version it is associated with - although you may not know at all if the information contained in it is applicable to a specific product or device?

The use of helpdesk tickets as a BZ does not solve the problem of involving people in searching for answers using it. In fact, the mass of tickets from the help desk can make the solution of the problem even worse . Imagine: every time a problem occurs, a new ticket is created, and when you do a search on a knowledge base (for example, on some old ticket), using a keyword, or simply choosing a product or device, you are given much more search results, where every ticket that matches your criteria appears.

Tickets collected on the help desk do not always represent a source of documentation for self-help. Not all IT employees are the best writers in the world, and in the tickets themselves there is something related to their method of collection ... let's call it an “informal” language that you most likely do not want to pull to the surface and demonstrate to your end users. For example, a user who has entered your knowledge base is trying to solve the problem himself, instead of asking for this help desk, he may not like it if he finds something like “Restart a stupid user computer”. Technicians may not provide any details. For example, often as a decision on the ticket is written "corrected" - that is, nothing useful for the decision. However, the use of helpdesk tickets as a source for the knowledge base is not so far from the real situation correction.

Unification of the knowledge base

There are two things with which you can try to turn tickets from the help desk into useful articles of the BR. First, some automation is required. When a new ticket is created, the system, where it is done, should automatically review the last tickets and present them as candidates for a solution to the technical expert who is going to work on the problem.

A great example of how this can be done if you ask a question is StackOverflow.com; by itself it already represents a combination of tickets / knowledge bases. It automatically searches for the latest questions and presents them visually in a separate way: they are inserted below your question, but above the field where you enter the details of your request, as shown in Figure 5.4. This forces you to forcibly view assumptions from the knowledge base, so that you can quickly see that perhaps your question already has an answer.

Figure 5.4: Expected answers to a question.

As you begin typing the details of the question, irrelevant assumptions begin to disappear from the main field, again helping you use the database of past answers, instead of requiring you to explicitly search at each additional step.

The unified system also helps to make this additional step (Fig. 5.5), either by including potentially relevant tickets to the search results, or by tying them to a newly created document. Thus, the system can give the technician an advantage: he starts to solve the problem, having an understanding of similar situations in the past, and how, at the same time, their solutions look.

Figure 5.5: Using old tickets to solve new problems.

In fact, for automatically generated tickets, the system can potentially do a very good job of looking for old tickets that are relevant to the problem. Since the system does not forget to take additional steps, it can include additional search criteria, such as for example the source of the problem, the affected devices or services, and so on. A technician may not guess to include all the details, because they will produce a very large number of results, which often pushes off the use of search in the first step. Obtaining a narrow result from which to start, the system automatically linking the tickets will make it more likely to have relevant information on hand. Such a system can be made even better if the system for working with the help desk included the ability to set pairs of check marks (check boxes) on their tickets. When closing the ticket, the technician should be able to independently write down:

- Does this ticket contain a good faith solution? For example, sometimes a technician can solve a problem by looking at the contents of the old ticket. This means that the current ticket does not contain enough information about how the problem was solved. But if the expert has solved the current problem, and filled in the ticket with a detailed description of the solution, compared to what was done before, then the current ticket can be labeled as a “solution” that will make it appear in the top lines of the search results.

- Does this ticket contain a solution suitable for the end user and which can be used later on as a self-service material? Most ticket tracking systems today contain “private” and “public” fields, which helps to ensure that end users will not see information that users might perceive inadequately, although it is assumed that administrators can sometimes write something on the ticket. At the same time, having on hand the unequivocal indications that this ticket is suitable for use outside the IT service and contains solutions suitable for independent use by the end user, it is possible to build a really working self-service knowledge base.

Figure 5.6. shows how the system can implement this - in this case, it is not a check box; the system uses the drop-down menu of the “visibility” item to change the status of the ticket from the state “on hold” to “published”

Figure 5.6: Visibility Ticket Management

The mere presence of these checkboxes (or other indicators) can serve as a reminder to technicians that documented solutions are a necessity. From the point of view of management, organizations can set certain quotas: at least 75% of closed tickets must contain a detailed solution, or refer to a ticket describing a detailed procedure for resolving the problem. Such metrics are tracked through internal reports in the ticketing system, and can be an additional way of verifying that closed tickets are really the basis for preserving knowledge.

Turning the ticket into an asset

The general idea is that you need to stop thinking that tickets are only suitable for tracking problems and work on creating a full cycle of them to solve problems. To benefit from this, ticket-as-solution must overcome a number of common human prejudices and implementation problems that have prevented them in the past:

- Technical specialists do not always use the search in the ticket base, as far as possible this should be done automatically, and tickets should be offered as a potential solution.

- The ability to use the search of technical specialists is not always perfect - so the unified system should, to a certain extent, automate this activity, and, using the available information, make the first attempt to search for relevant tickets.

- The ability to put their thoughts coherently on paper for technicians is not always a well-developed skill, so the system should, as far as possible, emphasize the need for complete solutions, and management should take this as a metric. Technicians, in turn, should be able to offer versions of the solution, both “internal” and suitable for “external use”, if such a need arises.

With the right system — especially one that can be integrated with the monitoring system — a truly unified environment is created — turning the solution into a problem can be done at the level of a single mouse click.

Past performance is an indicator of future results.

Another way to form the correct expectations from the level of service is to use historical data. I deliberately avoid the term “service level agreement ” because the SLA is a formal document, often incorporating elements of an organization’s policy. However, service level expectations are a level of service based on past performance and performance indicators that you quite realistically want to receive in the future. Ideally, the SLA should be based on these expectations of the real world, but only if you are able to meet them.

There is one problem that is contained in the SLA of many organizations - they are divorced from reality. Someone sets an ambitious goal to “look good”, promising availability at 99.999% and then vigorously asserts that they just “try to meet this figure,” someone chooses an overly cautious approach when setting conditions, forcing the organization to accept a lower level of service it could actually be.

Well, in case of failure - we can not forget about the tools we use. Everything comes back to the first chapter of the book when I wrote about management technologies for individual sections or "towers" with which IT is so inclined to work, as well as various specialized tools that we use to find solutions and fix problems. We have to use the same specialized tools for measuring performance levels. Due to the fact that each set of tools uses its own "conceptual language" and a set of metrics, it is rather difficult to bring everything into a single picture and use a single set of control values. Of course, it’s quite difficult to understand what levels of service we really have.

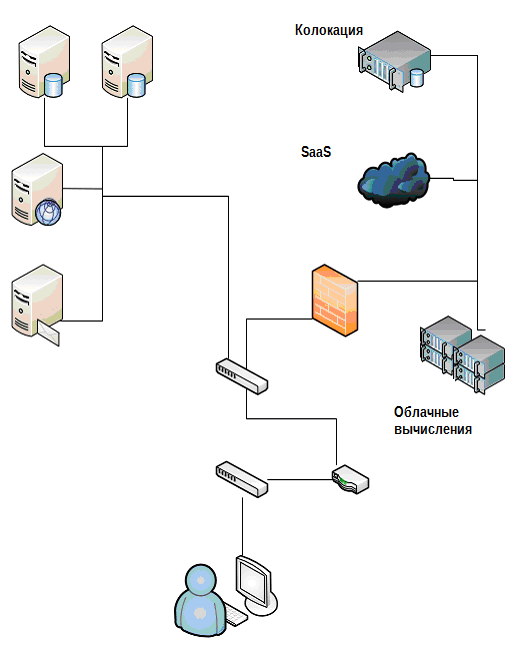

In summary: you have some existing environment. All political and internal problems are set aside, your existing infrastructure is able to provide you with a certain level of technically measurable performance and efficiency. You only need to understand and define it by writing in the form of understandable and easily explainable sets of metrics based on the current capacity of your infrastructure. This is difficult to do if you have a jumble of specialized tools, and even more so it is difficult to do if there are elements for outsourcing in your infrastructure. Start putting together cloud computing platforms, coallocated servers, SaaS platforms and so on, and you will see that your specialized toolkit is not able to provide you with enough information to solve. The question arises: how in this case can you establish a good level of expectations from the service?

This brings us back to the previous chapters in this book. For example, you have an excellent set of services and applications - who does not have it now? Figure 5.7 shows the infrastructure offering many different elements, some inside the datacenter, some outside.

Figure 5.7: The modern environment includes many components.

You start your measurements at one, the most important place: the end user. You place several sensors, agents, synthetic transactions, and anything else you need to understand what is happening - what users actually see, at a single moment , in terms of performance. It is necessary to monitor their work for several days, reflecting the real and work load, and you should not choose a weekend for monitoring, where the load values are noticeably lower and unrepresentative. Now you know what your infrastructure is really able to provide. It should be taken for granted that you can hardly expect something better, but also you should not expect something completely bad. If the service waiting level is not as good as your SLA - well, in general, everything is great. You can start looking for areas for improvement, pulling them up to the levels prescribed in the SLA.

You may need to collect information on the individual performance of each component - in this place a number of difficulties may arise. It is important that at this level of monitoring, you collect everything on one console, use one language (for describing processes) and use a single set of metrics. You need to find a range of performance values for each component operating under normal workday workload.

After making sure that each component works within the limits of the observed values, you should understand and appreciate the sensations of the end users associated with these measurements. These values are the basis for your monitoring values: everything that is outside of them should be notified in a timely manner.

Once we have set the expected levels of service, you can begin to measure the various levels of workload.See how things are going on heavily laden days and how they look on low-load days (for example, a day off). Then you will begin to feel how the feelings of users change, during periods of various loads, and how your infrastructure perceives the load, along with its elements.

Of course, it is imperative to make sure that all outsourcing elements are also included here. As I pointed out in previous chapters, monitoring all of this is a little different from monitoring things in your data center. You will need either a unified monitoring solution that has the capability for hybrid monitoring, or you will need a special set of tools to collect performance information from these parts of the infrastructure that are outside the geographical limits of your company.

Note that there are two sets of metrics for monitoring: performance and workload. Too often, I come across SLA, in which the load is not taken into account. "We will provide a response time within 100 ms", - Okay, but under what specific load? Perhaps I can provide you with a hundred millisecond response time under load, which I understand as normal, but if you start adding users and additional tasks, it is obvious that the response time will start to subside. Again, monitoring solutions can help us with this, not only measuring the performance of such things as the processor, memory, disks, and so on, but also the workload expressed, for example, in the number of processed transactions, the number of routed network packets, and so on. . It is important that yourPerformance expectations also included the concept of workload — this is needed to form service level agreements in the future.

This is a performance database .

All the data on the health need not only somewhere to collect, but also somewhere else to store . This is the same functionality that many monitoring systems miss: they monitor in real time and report problems, but they do not always save the information passing through them. Let's expand our example with a database on performance (

Fig. 5.8 ). Figure 5.8: Add a database with performance information to the environment.

The meaning of this illustration is that you need to collect information from each component - even from those that are outsourced to this database. What for? There are two reasons:

- , , . , , SLA.

- , . , – . , : «, , 1%, 0,75%? , SLA 6 .»

And to be honest, a good monitoring solution should not show you the standard “trend line” of your performance in the first step. A simple indicator with an arrow will suffice: “You are in line with your SLA, and based on current prospects, this will continue to be observed in your foreseeable future.” Or, “You meet the conditions of your SLA, but, honestly, based on current data, you will not be able to comply with the SLA after one or two months.”

And from now on , you can begin to understand the charts and graphs that provide you with detailed information, so that you can find a component or components that are a bottleneck in the system, and begin to plan ahead for an increase in the capacity of your resources, before an SLA mismatch occurs.

Results

Embrace the past, and your future will be better - this is what we talked about in this chapter. Do you collect information from tickets in order to solve problems faster and better in the future, or collect information on system performance: for reasonable agreements on service expectations and the correct calculation of resource capacity, all this concerns the preservation and management of historical data on my feet in the future.

In the next chapter ...

In the last chapter of this book, we are going to go through this path once more from the very beginning, and look at unified management from the point of view of studying cases. I will use my practical and consulting skills to create a composite case, outlining the elements of unified management together to show you what a modern, truly united environment can look like. I will show you the specific problems in each environment and explain how joint management helps to solve these problems better and more efficiently.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/175039/

All Articles