On the laws of universality or what Tetris can tell us about coffee stains

The next morning, after a large blizzard sweeping the northeast United States, I was sitting in my car, ready to defy dangerous road conditions to go to a local cafe. My home in New Jersey was outside the main path of the storm, so instead of snow drifts we were greeted by a mixture of sleet and freezing rain. And sitting in my car, I could not help but be fascinated by these strange patterns of ice floes forming on the windshield. Here is what I saw:

When I looked at this miniature world created on the windshield as an alien landscape, I thought about the physics of these patterns. Later, I learned that these ice patterns are associated with a very active area of research in mathematics and physics known as universality . The basic mathematical principles behind which these intricate patterns are hidden apply to some unexpected things, such as coffee rings, the growth pattern of the bacterial colonies, and the movement of the flame on cigarette paper.

Let's start with a simple example. Imagine a game similar to Tetris, but with only one type of blocks - 1 x 1 square. These identical blocks fall at random, like raindrops. Question: which block pattern do you expect to see as a result?

')

You might assume that, since the blocks fall randomly, everything will end in a smooth, uniform pile of blocks, like piles of sand that gather on the beach. But this is not happening. Instead, we get jagged horizons, where tall towers stand next to deep hollows. Creating a high stack of blocks next to a low stack is as likely as creating next to another high stack.

This is not very similar to what I saw on the windshield.

This tetris-like world is an example of what is known as the Poisson process, which I wrote about earlier. The point is that chance does not mean uniformity. Instead, the confusion represents clusters like the jagged horizon of Tetris blocks, which you see above, or like the distribution of the Humming bombs that fell on London during World War II .

This Tetris example may seem a bit abstract, so let me introduce you to a guy who accepts abstract ideas and links them to real-life examples. His name is Peter Juncker , and he is a physicist from Harvard.

Yunker was curious about the causes of the ring stains of coffee. In 1997, a group of physicists figured out why a coffee stain forms a ring. As the coffee evaporates, the liquid rushes from the center to the edge of the drop, trapping the coffee particles along with it. The drop begins to level off. In the end, there remains a thin ring, as the coffee particles all rushed to the edge of the drop. Here is an amazing video captured by the Juncker team, which shows how this process looks.

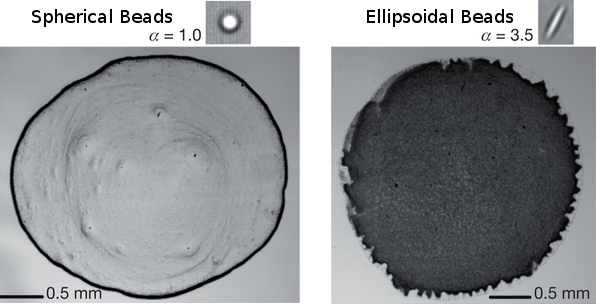

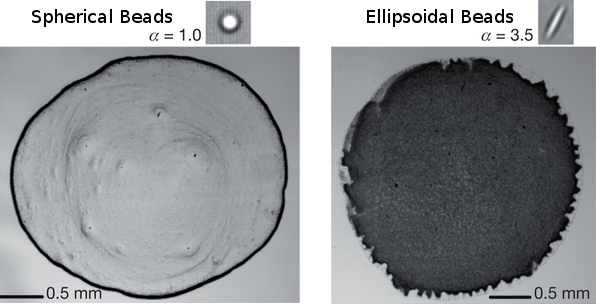

What Junker showed is really very elegant. He discovered that the reason that the coffee drop forms a ring is in the form of a coffee particle. Look at a drop of coffee under the microscope and you will find small, round caffeines. If you take a closer look at the edge of the coffee drop, you will see particles sliding past each other, like blocks in our Tetris . In fact, Juncker showed mathematically that the nature of the accumulations of these coffee particles is exactly the same as our randomly falling Tetris blocks!

But what is surprising! Juncker and his colleagues also found that if we replace the spherical particles with more elongated ones, like ovals, we will get a completely different picture. Instead of a ring, we get a solid spot. The video above shows how this happens.

In one case, we get a ring, and in the other - a continuous spot. So why does the particle shape change the overall growth pattern? To understand why oval particles behave differently, we will set up our Tetris game. Let's call the new version - Gummy Tetris.

In Lipkom Tetris, the block continues to fall until it touches the other, standing in place of the block, at least on one side. As soon as a falling block comes into contact with a non-falling block, the first one immediately freezes in place.

This is a small change in the rules, but it has quite big consequences. In a regular Tetris, you need a lot of blocks to fill deep gaps; in Lipk Tetris, you can fill a large gap with one block. Very quickly, the height difference between the towers begins to level off. Instead of a rough, jagged horizon in the usual Tetris, the horizon in the sticky version of the world is smoother.

It looks much more like a windshield pattern!

And here is the essence. While spherical particles behave like ordinary Tetris blocks, oval-shaped particles behave the same way as Sticky Tetris blocks . At that moment, when the moving oval coffee particles touch the stills, they stick in place. Instead of jagged horizons, we get this Swiss cheese, a complex structure of sprawling filaments separated by holes and slits.

Thus, we have two essentially different types of growth processes. On the one hand, we have particles that accumulate like ordinary Tetris blocks or like caffeinas in a coffee ring. Here are animations of real data from Juncker's lab showing how it looks.

On the other hand, we have particles that accumulate as sticky blocks or like oval caffeinos. The growth of these particles is as follows (again, this is real data).

Obviously, these are two qualitatively different patterns.

But they are also quantitatively different. Remember that in the world of ordinary Tetris we end up with a jagged horizon, while in the world of Gummy Tetris, the horizon is smoother. By studying how the upper layer of particles (horizon) expands over time, physicists can classify growth processes. In the jargon of the field, processes that grow at different speeds belong to different universality classes .

Let's say you study how ice particles are condensed on your windshield. If the speed with which the horizon expands corresponds to the blue curve on the graph above, then the process of thickening ice is in the same universality class as Tetris. If it coincides with the violet curve, then it falls into the universality class of Sticky Tetris. The key point is that many seemingly different physical systems, with mathematical analysis, show identical growth models. These slightly mysterious tendencies of the same behavior of very different things reflect the essence of universality .

Moreover, there is a rich mathematical theory behind the sticky Tetris universality class, described by an equation known as the Kardar-Parisi-Zhang equation (KPG).

This deep connection between the coffee rings and the CPJ equation took Peter Juncker off guard. According to Juncker: “ Alexey Borodin , a mathematician at MIT, contacted us after we published an article about how the shape of particles affects their deposition in the coffee ring. He watched our experimental videos online and remembered the modeling that he had done before. We would never have begun to study this area if Alexey had not attracted our attention to her. ”

And this class of sticky Tetris universality arises in all sorts of strange places. Such an example is burning paper. During the 1997 physics experiment , the copy paper was set on fire at one end and the front of the flame was fixed while it was burning. Here is a sketch of what happened.

The flame develops in a smooth, wavy pattern as it burns through the paper. And when physicists studied in detail the behavior of this flame front, they found that it exactly coincides with the predictions of the KPW equation. They repeated their experiment using tissue paper and got the same results.

And another very unexpected and elegant example is bacterial colonies. A group of Japanese physicists in 1997 showed that in a certain nutrient medium, the edge of the bacterial colony grows exactly in the manner predicted by the universal class CSF. Here is the animation of this in action. You are looking at enlarged photos of the edge of the bacterial colony as it grows in a Petri dish .

Now, if you think about it, you will discover something deeply mysterious . Colonies of bacteria, traveling flames and particles of coffee are all completely different systems, and there is no reason to expect that they must obey the same mathematical laws of growth. So what is behind this mysterious versatility? Why do such different things play by the same rules?

You may have noticed that all these examples look a bit fractal . It turns out that the phenomenon of universality is inextricably linked with the fact that these systems are self-similar , like fractals. As I zoomed in on the ice particles on the windshield, the overall picture looked the same. The same is true for the flame front, the edge of a bacterial colony, or the Sticky Tetris horizon. Here is an example of a self-similar curve (or scale-invariant , as physicists like to call it).

Surprisingly, this self-similarity means that many tiny details, such as bacteria or caffeines, do not change the overall picture. According to Peter: “The fractal nature of these growth processes is important for their universality. In order to be universal, the system cannot depend on microscopic details, such as particle size or scale of interactions (this does not apply to form - approx. Transl.). Thus, the universal system must be scale-invariant. ”

Which brings me back to the ice particles on the windshield. They stick together in these wonderful fractal patterns, which, in my opinion, are very similar to Gummy Tetris. I wanted to find out if there is a connection between these particles of ice and the classes of universality of the CSW, and asked Peter Juncker.

He replied: “These videos are fantastic. I agree with you that the main process taking place here is very similar to the PCM process. This can be an excellent example of why it is difficult to determine the processes of QPL in real experiments. Changes in these structures have a strong influence on the overall development of the system. But it is likely that this system has the same growth rates as the HRC processes. ”

The part of physics that makes these pieces short-lived makes them difficult to study. And so, let me finish a short video on growth and longevity;)

When I looked at this miniature world created on the windshield as an alien landscape, I thought about the physics of these patterns. Later, I learned that these ice patterns are associated with a very active area of research in mathematics and physics known as universality . The basic mathematical principles behind which these intricate patterns are hidden apply to some unexpected things, such as coffee rings, the growth pattern of the bacterial colonies, and the movement of the flame on cigarette paper.

Let's start with a simple example. Imagine a game similar to Tetris, but with only one type of blocks - 1 x 1 square. These identical blocks fall at random, like raindrops. Question: which block pattern do you expect to see as a result?

')

You might assume that, since the blocks fall randomly, everything will end in a smooth, uniform pile of blocks, like piles of sand that gather on the beach. But this is not happening. Instead, we get jagged horizons, where tall towers stand next to deep hollows. Creating a high stack of blocks next to a low stack is as likely as creating next to another high stack.

This is not very similar to what I saw on the windshield.

This tetris-like world is an example of what is known as the Poisson process, which I wrote about earlier. The point is that chance does not mean uniformity. Instead, the confusion represents clusters like the jagged horizon of Tetris blocks, which you see above, or like the distribution of the Humming bombs that fell on London during World War II .

This Tetris example may seem a bit abstract, so let me introduce you to a guy who accepts abstract ideas and links them to real-life examples. His name is Peter Juncker , and he is a physicist from Harvard.

Yunker was curious about the causes of the ring stains of coffee. In 1997, a group of physicists figured out why a coffee stain forms a ring. As the coffee evaporates, the liquid rushes from the center to the edge of the drop, trapping the coffee particles along with it. The drop begins to level off. In the end, there remains a thin ring, as the coffee particles all rushed to the edge of the drop. Here is an amazing video captured by the Juncker team, which shows how this process looks.

What Junker showed is really very elegant. He discovered that the reason that the coffee drop forms a ring is in the form of a coffee particle. Look at a drop of coffee under the microscope and you will find small, round caffeines. If you take a closer look at the edge of the coffee drop, you will see particles sliding past each other, like blocks in our Tetris . In fact, Juncker showed mathematically that the nature of the accumulations of these coffee particles is exactly the same as our randomly falling Tetris blocks!

But what is surprising! Juncker and his colleagues also found that if we replace the spherical particles with more elongated ones, like ovals, we will get a completely different picture. Instead of a ring, we get a solid spot. The video above shows how this happens.

In one case, we get a ring, and in the other - a continuous spot. So why does the particle shape change the overall growth pattern? To understand why oval particles behave differently, we will set up our Tetris game. Let's call the new version - Gummy Tetris.

In Lipkom Tetris, the block continues to fall until it touches the other, standing in place of the block, at least on one side. As soon as a falling block comes into contact with a non-falling block, the first one immediately freezes in place.

This is a small change in the rules, but it has quite big consequences. In a regular Tetris, you need a lot of blocks to fill deep gaps; in Lipk Tetris, you can fill a large gap with one block. Very quickly, the height difference between the towers begins to level off. Instead of a rough, jagged horizon in the usual Tetris, the horizon in the sticky version of the world is smoother.

It looks much more like a windshield pattern!

And here is the essence. While spherical particles behave like ordinary Tetris blocks, oval-shaped particles behave the same way as Sticky Tetris blocks . At that moment, when the moving oval coffee particles touch the stills, they stick in place. Instead of jagged horizons, we get this Swiss cheese, a complex structure of sprawling filaments separated by holes and slits.

Thus, we have two essentially different types of growth processes. On the one hand, we have particles that accumulate like ordinary Tetris blocks or like caffeinas in a coffee ring. Here are animations of real data from Juncker's lab showing how it looks.

On the other hand, we have particles that accumulate as sticky blocks or like oval caffeinos. The growth of these particles is as follows (again, this is real data).

Obviously, these are two qualitatively different patterns.

But they are also quantitatively different. Remember that in the world of ordinary Tetris we end up with a jagged horizon, while in the world of Gummy Tetris, the horizon is smoother. By studying how the upper layer of particles (horizon) expands over time, physicists can classify growth processes. In the jargon of the field, processes that grow at different speeds belong to different universality classes .

Let's say you study how ice particles are condensed on your windshield. If the speed with which the horizon expands corresponds to the blue curve on the graph above, then the process of thickening ice is in the same universality class as Tetris. If it coincides with the violet curve, then it falls into the universality class of Sticky Tetris. The key point is that many seemingly different physical systems, with mathematical analysis, show identical growth models. These slightly mysterious tendencies of the same behavior of very different things reflect the essence of universality .

Moreover, there is a rich mathematical theory behind the sticky Tetris universality class, described by an equation known as the Kardar-Parisi-Zhang equation (KPG).

This deep connection between the coffee rings and the CPJ equation took Peter Juncker off guard. According to Juncker: “ Alexey Borodin , a mathematician at MIT, contacted us after we published an article about how the shape of particles affects their deposition in the coffee ring. He watched our experimental videos online and remembered the modeling that he had done before. We would never have begun to study this area if Alexey had not attracted our attention to her. ”

And this class of sticky Tetris universality arises in all sorts of strange places. Such an example is burning paper. During the 1997 physics experiment , the copy paper was set on fire at one end and the front of the flame was fixed while it was burning. Here is a sketch of what happened.

The flame develops in a smooth, wavy pattern as it burns through the paper. And when physicists studied in detail the behavior of this flame front, they found that it exactly coincides with the predictions of the KPW equation. They repeated their experiment using tissue paper and got the same results.

And another very unexpected and elegant example is bacterial colonies. A group of Japanese physicists in 1997 showed that in a certain nutrient medium, the edge of the bacterial colony grows exactly in the manner predicted by the universal class CSF. Here is the animation of this in action. You are looking at enlarged photos of the edge of the bacterial colony as it grows in a Petri dish .

Now, if you think about it, you will discover something deeply mysterious . Colonies of bacteria, traveling flames and particles of coffee are all completely different systems, and there is no reason to expect that they must obey the same mathematical laws of growth. So what is behind this mysterious versatility? Why do such different things play by the same rules?

You may have noticed that all these examples look a bit fractal . It turns out that the phenomenon of universality is inextricably linked with the fact that these systems are self-similar , like fractals. As I zoomed in on the ice particles on the windshield, the overall picture looked the same. The same is true for the flame front, the edge of a bacterial colony, or the Sticky Tetris horizon. Here is an example of a self-similar curve (or scale-invariant , as physicists like to call it).

Surprisingly, this self-similarity means that many tiny details, such as bacteria or caffeines, do not change the overall picture. According to Peter: “The fractal nature of these growth processes is important for their universality. In order to be universal, the system cannot depend on microscopic details, such as particle size or scale of interactions (this does not apply to form - approx. Transl.). Thus, the universal system must be scale-invariant. ”

Which brings me back to the ice particles on the windshield. They stick together in these wonderful fractal patterns, which, in my opinion, are very similar to Gummy Tetris. I wanted to find out if there is a connection between these particles of ice and the classes of universality of the CSW, and asked Peter Juncker.

He replied: “These videos are fantastic. I agree with you that the main process taking place here is very similar to the PCM process. This can be an excellent example of why it is difficult to determine the processes of QPL in real experiments. Changes in these structures have a strong influence on the overall development of the system. But it is likely that this system has the same growth rates as the HRC processes. ”

The part of physics that makes these pieces short-lived makes them difficult to study. And so, let me finish a short video on growth and longevity;)

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/173905/

All Articles