Don Jones "Creating a unified IT monitoring system in your environment" Chapter 1. Managing your IT environment: four things you do wrong

From translator

From the moment I started monitoring, quite a long time passed, and if at first monitoring was a specific technical task, then over time its meaning, (at least for me personally), moved up a lot of steps and now stands in one of the main tools for doing business, such as, for example, the corporate information system.

Having started to publish in Habré some of my articles and translations on the subject of monitoring IT infrastructure, I again had to deal with a very narrow and technical understanding of this topic, which I once had and therefore I once had the idea to present it systematically. I even began, without haste, to write an article on this topic, but intuitive things didn’t fit the paper very well - there was no forest for the trees. Of course, we all have Google and the opportunity to see what other authors are writing, but it was not there. Countless articles and blog posts were devoted to the technical aspects of hacking up another monitoring system for the next version of the operating system and the associated heroic overcoming of difficulties. There were very few articles on monitoring methodology, principles for choosing metrics, proper building of the process and linking it with the business, and they also described some particular cases of monitoring used to solve a particular problem and nothing more. And then I accidentally fell into the hands of a very small book by Don Jones "Creating a unified IT monitoring system in your environment (ENG)".

This was what was needed - it described the philosophy, outlined a number of concepts and listed some directions, following which one can achieve that the monitoring system works for IT and the organization as a whole, and the general picture finally began to emerge from particulars. I came up with some ideas on my own, but I was glad that I had found a lot of new things, which seemed to me interesting and worthy of discussion among specialists. And what is most surprising is that this book was free.

Why did I decide to translate it? I, of course, have no doubt that in Habré 2/3 inhabitants read and speak English well, but you have to think about those who don’t know how to do it or he doesn’t have enough patience to master so many English letters. I personally prefer to read in Russian, especially when it does not concern terminology with a controversial translation into Russian (hello, PMBOK!), But is connected with life and rather emotional topics. Translation is my personal initiative, I don’t receive any material benefits from it and I see as my only task bringing new knowledge to a wide range of readers, hoping that someone might be able to reflect on their daily problems and see that their solution exists. My only merit is in retelling Russian words of thoughts, expressed by the author. :)

')

In addition, I would really like to discuss the ideas and suggestions contained here. It is no secret that the difference in mentality, way of life, legal base can generate specific problems that differ from those described by the author, and certainly there are already tried ways to deal with them, just a large part of the IT-people are not aware of this.

This book, first of all, will be useful for IT managers - heads of departments and services, IT monitoring project managers, key and leading specialists, system administrators who are going to become managers some day and try to understand what their activities mean for the organization as a whole. .

PS All highlighting in italics in the text is copyright, unless otherwise specified.

Content

Chapter 1. Managing your IT environment: four things you do wrong

Chapter 2. Elimination of management practices for individual sites in IT management

Chapter 3. We combine everything into a single IT management cycle

Chapter 4. Monitoring: a look beyond the data center

Chapter 5: Turning Problems into Solutions

Chapter 6: Unified Case Management

From the author. Introduction to Realtime Publishers

For seven years, Realtime produced dozens of high-quality books destined to be distributed in electronic format; moreover, free for you, readers. We managed to make this publishing model workable through generous support and cooperation with our sponsors, who agreed to take the burden of producing each book for the benefit of our readers.

Although we have always offered our publications to you completely free of charge, but do not hesitate for a minute that quality means less to us than our main goal. The purpose of my work is to be sure that our books are just as good, and in most cases even better than any printed book that will cost you $ 40 or more. Our electronic publishing model has a number of serious advantages over printed books: you get chapters literally right after our authors write them (this is the “real-time” aspect present in our model), and we can make changes to them so that we can reflect new trends in technology. I would also like to emphasize that our books are not advertising and not white papers. We are an independent publishing company, and an important aspect of my work is to provide a platform for our authors, so that they have the opportunity to express their expert opinion without any restrictions or reservations. We maintain complete editorial control over our publications, and I am proud that we have managed to create so many quality books in recent years.

I would like to invite you to visit our site nexus.realtimepublishers.com , especially if you received this book from your friend or colleague. We have a large number of other books on a variety of topics, and, undoubtedly, you will find something that you may be interested in - and this will cost you nothing. We hope that you will continue to visit Realtime for educational purposes in the future.

With pleasure,

Don Jones, editor of the series.

Chapter 1. Managing your IT environment: Four things you do wrong

At the very beginning of the IT industry, the concept of “monitoring” meant a person who was wandering in search of blown electronic tubes among the cabinets where the mainframe was located. Of course, this was not quite the right way to identify faulty vacuum devices that worked in slightly more difficult conditions than they were intended for. Thus, monitoring, at that time, was an exceptionally reactive way of responding to problems.

At the same time, the “help desk” was the same guy who answered the phone calls, when one or two of the top ten “computer people” needed help in pushing cards into the reader, in tracking down burned-out lamps, and so on. The concepts of tickets, knowledge bases, service level agreements (SLAs) have not yet been invented. IT management has improved significantly since that time, but unfortunately, not to the level it could or should have been. Definitely, our work tools have become significantly more complex and mature, but the way we use these tools — our IT management processes, in some ways, still remains at the level of reactive ways to replace radio tubes.

Some of the concepts on which IT management practices in many organizations are based actually harm them, although according to the logic of things, IT should support their work. The discussion in this chapter will focus on a few major topics that will smoothly move into the next chapters of the book. The goal is to change your thinking about how IT management should work, and in particular, monitoring; what value should IT bring to the organization, and how should you turn towards better management of your IT environment.

IT management: how we got here, and why we have what we have

At the beginning of IT, we dealt with relatively simple systems, even simplified, if we consider them through the prism of today's standards. The team of IT specialists often consisted of people who were able to solve any of the problems that had arisen, if only because the systems did not have such a large number of “moving parts” if we represent IT in the form of a car. The car was complicated in its own way and was able to do various things, but at the same time it was completely understood by a single person.

As the IT car began to turn into a spacecraft, we gradually needed specialization. Personal systems have become so complex that we need experts with specific knowledge who are able to monitor, maintain and manage each system.

Messaging systems. Database. Infrastructure components. Directory Services.

The vendors creating these systems, together with third-party manufacturers, developed a toolkit that helps our experts monitor and manage each system. And it was there that everything went wrong, although at some point in time everything looked great, and, in fact, perhaps there was no other way to perform these tasks, but this is what led to the formation of their own domain (specific-domain silos) - each with its own individual tools, procedures and expertise - what has become a problem of “individual towers” within many IT services.

And now let's move quickly to the present, when our systems have become significantly more complex, with a huge number of connections and, at the same time, they are increasingly located outside our own data center. When a user encounters a problem, it is quite obvious that they cannot tell us which of our complex systems have a problem. They simply tell us what they see and how, in their opinion, this problem manifests itself, which may be the cumulative result of the interaction of several systems and their interdependencies. Our users see a holistic environment - “IT” in general, which is somewhat different from what we see from our back-end: databases, servers, directories, files, networks, and much more. As a result, we often spend a lot of time tracking down the true cause of the problem, and, worse, we often don’t even see the impending incident, because the problem is present only when you look at the end result of the whole environment, and not some of its individual parts. Users feel completely detached from the process, and besides, they are still separated from IT by “help desk”, which is sometimes useful and sometimes not. IT management, at the same time, is experiencing difficult times, completely immersed in problems of performance, availability, and so on, because they have to use metrics that are specific to each system in the network, instead of considering the environment as a whole.

The way in which we built our IT services led us to very specific problems at the business level, and they became common concerns and sources of complaints around the world:

- IT has difficulty determining and matching the business level SLA. “The mail server will work 99% of the time” - this is not a business SLA, this is a technical agreement. “E-mail will be freely transferred between external and internal users of the mail system 99% of the time” is a business-level SLA, but it is rather difficult to measure, because this statement involves significantly more systems in its execution than a simple mail server (Actually, It is extremely imprudent to subscribe under the responsibility for systems that are outside the limits of the responsibility of the local IT service. Let's hope that the author did not mean anything else - av . perev) .

- IT has difficulty in proactively predicting complex situations based on the overall health of IT systems, so IT services, for the most part, remain reactive in solving problems.

- When a problem happens, IT often spends too much time for a detailed explanation of its cause.

- The concepts of productivity and “system health” used in IT are based on systems — database servers, directory services, network devices, and so on — and not on how users and the organization generally perceive the services provided by these systems.

- IT service is working hard to adapt new technologies that can benefit business. It sounds weird, but the fact remains that IT is often the most change-resisting part of an organization, because change is usually the trigger for many troubles. Defective systems do not help anyone, but the inability to quickly introduce changes to the company’s structure can also be a threat to the organization’s competence and flexibility in the near future.

- The IT service is working very hard, adapting new technologies that significantly go beyond the experience and competence of the team or are beyond physical accessibility, especially if it concerns the mass of outsourced offers, usually combined under the concept of "cloud computing." These technologies and approaches are so different from what they were before that IT does not feel confident in monitoring and managing new systems. Therefore, they resist the implementation of such decisions, fearing that their implementation will harm the organization.

- Even with modern self-help systems that are in the service of the help desk, users feel incredibly helpless and divorced from the situation when it comes to IT.

All of these business stumbling blocks are a direct result of how we manage IT. Our monitoring and IT management processes typically have four major problems. Of course, not every organization has them all at once, the majority, at least, have heard of them and are working hard to counter them. However, companies need to clearly understand that they have an idea of all four problems, and if this is done, then almost immediately you can begin to address the business issues that we mentioned earlier.

Problem 1: You manage IT by individual sites ("towers").

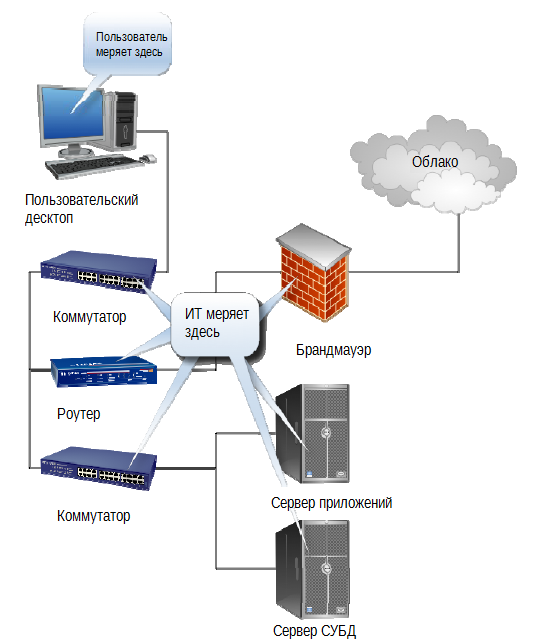

Figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3 illustrate one of the fundamental problems in IT monitoring and management today.

Figure 1.1: Measuring Windows OS performance in Windows Performance Monitor.

Figure 1.2: Measuring the performance of a database server in SQL Server Performance.

Figure 1.3: Measuring CPU usage on a router

The numbers represent the performance / load status of the various components of the IT system. Each of these images is created by a tool that is more or less specialized to track the results of a specific task. Software that is used to monitor the performance of a router, for example, is not able to reproduce a similar picture for a database server or even for a router that is located on another network.

This is such a common and fundamental problem that most IT experts do not even want to admit that this is a problem. Using these separate, strictly specific tools is such an ingrained and natural practice in IT that most of us simply cannot think about anything else. Nevertheless, we need to leave in the past the use of these specialized tools as a first line of defense when it comes to monitoring and troubleshooting.

Why?

One of the main reasons is that these tools do not allow us to stay on the “one page”. When specific tools are involved, the IT experts cannot get a logical and multi-disciplinary discussion. “I look at the DBMS server and its performance is more than 200 transactions per minute,” says one expert. "Well, this can be a problem, because the router processes more than 10,000 packets per minute." Two specialists do not have a common language in which it would be possible to talk productively about productivity, because each of them is locked in his own "tower" - deep technical aspects of the technologies with which they mostly work.

A field-specific toolkit also encourages the worst practices in all IT services, namely, considering systems in isolation. The DBA administrator has no idea how the routers work, what is the good or bad performance of the mail server, or what you need to look at to make sure that the directory service infrastructure works as expected. Therefore, the DBMS administrator puts horse blinders on himself and looks only at the database servers, but his servers do not work in a vacuum; Their work is influenced by other systems, as well as they themselves affect the rest of the infrastructure. Everything works together , but we cannot see it , because we use too specialized tools. Basically, this means that we need new tools that will allow specialized tools designed to access individual “towers” to work in a single team, moving the information needed by everyone into a common context. Without a doubt, specialized tools will always be in demand, but they will not be our first line of access to information.

Jerry works in a typical IT department in a medium-sized company. His specialty is the administration of Windows servers. His team has specialists in web applications, MS SQL Server and Oracle, VMware vShpere, and network infrastructure. Some corporate applications are outsourced: CRM (customer relationship management) and mail.

An incident recently occurred that stopped sending emails to customers containing an electronic order confirmation. To solve the problem, Jerry was initially attracted, on the assumption that the reason could have been in the postal service that was outsourced. However, Jerry found out that the mail passes normally. He referred the problem to the web solutions specialist, who confirmed that the website itself is working fine, but the mail that it sends is wrapped somewhere. Jerry filled out a ticket at a mail hosting company, to which she replied that their systems were working fine and that it would be nice to check the passwords that the client’s web servers use.

It took more than a day of correspondence with the hosting company and various experts, and the problem finally went down to the corporate firewall. Not so long ago, an update was made to the new version, and it blocked outgoing mail traffic from the perimeter of the corporate network, just where the company's web servers were located. They called a network specialist, he reconfigured the firewall and the problem was solved.

This story accurately illustrates the essence of the problem: if we manage our teams of IT specialists as fiefdoms, we significantly hamper their ability to work together to solve problems. The fact that they need specialized tools to do the work should not be an obstacle to the destruction of the borders of individual possessions and more effective joint work. This becomes especially important when some parts of the infrastructure are being outsourced; hosting companies are sovereign “states” because they are not responsible for any other systems except those that they provide. However, the dependence of our systems and processes on their systems means that our own team must be able to monitor and know what to do with them in the event of a problem, as if these systems were right in our data center

Problem 2: There is no connection between your users, the service desk and the IT management.

Communication is a key component that makes any team work; and in this case is not an exception “team”, which is your organization. In the case of IT, we usually use systems for helpdesk organizations, implying that this is a reasonable way to communicate, but this is not always enough. Helpdesk systems, as a rule, are built on the concept of reacting to a problem and the subsequent management of the reaction, and by definition, they are practically not proactive .

For example, how will you inform your users that this system will have reduced performance or will be disabled for a certain period of time? Perhaps by email, which creates a couple more problems:

- An important message tends to get lost in the influx of emails that a user receives every day.

- Users who do not understand or have not received the message have a habit of going through the help desk, which has no way to intervene in thought processes and explain in a contactless way to them what the event was planned for, which users consider to be a “problem”.

Most IT teams have a great idea of what is needed for successful communications throughout the organization, for example:

- Service Level Agreements (SLA)

- The current status of the SLA - how they are performed.

- Planned outages and performance degradations

- Average response time of individual services

- Current problems that are in the works.

The challenge for most IT teams is to share information on these topics throughout the entire organization. Some companies rely on e-mail, which, as I indicated earlier, may be insufficient and not quite effective. Some offices use an internal website, such as the SharePoint portal where notes are published, but these sites do not have direct integration with the help desk, so an extra step is needed to synchronize information in both systems, and users are required remember that the portal must be periodically entered.

Tom works as a sales manager for a medium-sized manufacturing company. Recently, an application that Tom used to track prospective customers and create new accounts began to respond very slowly and, by the end of the day, completely stopped. Tom’s initial response was to call the help desk of the IT services company. Helpdesk technical specialist said to Tom in a tired voice: “We are in the know, we are working on it,” and hung up. Tom has no information about when the system will work again and he was afraid to call back to the help desk and find out the state of affairs in more detail.

At the end of the day, help desk registered calls from almost every seller, each of whom called on his own initiative, wanting to understand what was going on. In the end, the help desk stopped registering calls, telling each caller that the "ticket is already open" and hanging up. Finally, one of the IT managers finally sent out an e-mail explaining that the server had failed and the application would not work until the next morning. Tom would very much like to know this before; After all, he was going to call clients all day, but if this information that the application would not be available for such a long time, arrived in a timely manner, he would have done something else, or even took time off.

Managerial communications are just as important as they are complex. Ensuring honest numbers in service levels, response times, lack of services, and so on is all very important if management needs to make well-developed IT solutions, but it is often not easy to get reliable information.

Problem 3: You measure wrongly and not there.

This problem, perhaps, is in the heart of any IT service - inaction in adapting technology to the needs of the business. The following example demonstrates just such a scenario.

. , , . - IT, . , : « . - , , , ».

. , - . , . , .

, -. , .

, , . -, , , , , , .

This kind of situation, unfortunately, often happens in many organizations. This example accurately illustrates what happens when several problems happen at the same time: IT does not work as a team, but as a group of disparate specialists, and each of these groups has its own understanding of the word “slow”. The main reason was that everyone was not measuring it . Figure 1.4 shows how an ordinary IT service sees a multi-component, distributed application:

Figure 1.4 IT Service's view of a distributed application.

They see the component parts. Experts on each component measure their performance using technical metrics such as processor utilization, response time, etc. When one of the components is out of acceptable values, one of the engineers starts checking it. Figure 1.5 shows how the user sees the same application.

Figure 1.5 A user's view of a distributed application.

The user does not see (very often - can not see) the internal structure. There is an application for it, and either it responds as expected or not. The user is absolutely indifferent whether a particular component works with an "acceptable level of processor utilization" - he does not know thatit means. He cares if the application works; which creates a large gap between the perceptions of the user and the IT engineer, as shown in Fig. 1.6.

Fig. 1.6. Performance measurement by user and IT engineer.

Users and IT services measure different things. In IT-oriented SLA, a specific response time for requests sent to the DBMS server can be specified, but this is of little use if the application is “slow” from the user's point of view. Worse, if we start migrating services and components to the cloud, we lose most of our ability to determine the performance of our components in the way we used to do this in our data center. Result? None of the parties will be satisfied with the provisions of such an SLA.

All this needs to be changed. We need to learn to measure things from the user's point of view. The performance of individual components is important, but only to the extent that it affects the overall performance felt in a particular workplace. We need to register such SLAs, in which both the user and the IT service are “on the same page”, then manage the implementation of these SLAs in the ways and tools that allow us to do this successfully. Some organizations report that they are moving, or have already moved to IT work based on the provision of services - this, in a broad sense, means that the company is looking for a way to implement the work of the IT service as a set of services for various departments of the organization and their users. However, in many cases,these “service-oriented” organizations are still focused on components and devices, which, generally speaking, is not at all a service-oriented approach. When your telephone exchange crashes, you don’t call the telephone company (perhaps from your mobile) and don’t start asking questions about switches and trunks — you ask when the usual buzzer will appear again in your handset. The internal structure for the user does not matter. The credit of your expectation is not based on how long the office of a single telephone company will be inoperable, you ask yourself how long you can afford to have a non-performing telephone connection. It is to such a model that information technology services should move.When your telephone exchange crashes, you don’t call the telephone company (perhaps from your mobile) and don’t start asking questions about switches and trunks — you ask when the usual buzzer will appear again in your handset. The internal structure for the user does not matter. The credit of your expectation is not based on how long the office of a single telephone company will be inoperable, you ask yourself how long you can afford to have a non-performing telephone connection. It is to such a model that information technology services should move.When your telephone exchange crashes, you don’t call the telephone company (perhaps from your mobile) and don’t start asking questions about switches and trunks — you ask when the usual buzzer will appear again in your handset. The internal structure for the user does not matter. The credit of your expectation is not based on how long the office of a single telephone company will be inoperable, you ask yourself how long you can afford to have a non-performing telephone connection. It is to such a model that information technology services should move.The internal structure for the user does not matter. The credit of your expectation is not based on how long the office of a single telephone company will be inoperable, you ask yourself how long you can afford to lack a proper telephone connection. It is to such a model that information technology services should move.The internal structure for the user does not matter. The credit of your expectation is not based on how long the office of a single telephone company will be inoperable, you ask yourself how long you can afford to lack a proper telephone connection. It is to such a model that information technology services should move.

Problem 4: You lose knowledge

The last problematic practice that we will consider is the loss of initial knowledge. Purely human weakness, and frankly, it is difficult to specifically address anywhere. To understand this, let's consider the usual case:

. . , - :

« Oracle», - , — « , - ».

« Oracle», — , « Oracle ».

«, . ».

« , !».

«, - … , ».

Unfortunately, too much knowledge accumulates in the minds of individuals. In fact, an even sadder truth is the way many companies “cope” with this problem - by refusing some IT professionals to take full vacations, not allowing them to engage in any other activity that takes them out of sight and reach - such as like learning outside the company, traveling to conferences, just everything that continues their education and allows them to acquire new skills.

It can be counted on the fingers of a company that made half-hearted attempts to build “knowledge bases”, in the hope that basic skills can be transferred to electronic documents, preserved and made more accessible. The problem is that many IT professionals are not necessarily good writers, so the process of filling the knowledge base for them will be very difficult. In addition, it takes time, which the organization is extremely reluctant to allocate for this purpose, especially in the face of daily urgent tasks and requirements.

As I said, this is difficult to fix. The IT service understands the situation and, as a rule, agrees that something needs to be done - but they are not technographers, and often have extremely limited capabilities for this. You can usually create some management requirements that will reflect that problems and their solutions must be registered in the form of tickets on the help desk, but searching in such a system can often be difficult or time consuming - just as it happens. when searching online; with all the wrong results that an immense mass fall out on the screen during the standard query procedure.

But we must find a way to solve this problem. Knowledge of the infrastructure of the company - and how to solve problems shouldbe accumulated and saved. This requirement will not only help resolve emerging issues in the future, but will also help prevent their occurrence, allowing you to make more informed IT decisions.

How accurate is unified management to correct problems?

This book is devoted to how to correct these four annoying moments, and the methods I propose for this can be put together under the umbrella of the consolidated concept of "unified management." At its core, unified management boils down to bringing everything together in one place.

We will break down the boundaries of “specific principalities” between individual IT disciplines, put everything we need on one console, make each specialist work on one common data set and force everyone to work together on the problem. We will do this in a way that will unite users, IT and managers into a single window of IT services and performance. We will give more transparency to such things as service levels, allowing users to seewhat happens in their environment and be more informed.

We will provide our users with information that they will understand, instead of using the obscure, purely technical metrics that we use in our back-end. We will rebuild the entire SLA concept into something that makes sense primarily for users and their management, which will allow us to withstand the transition to “hybrid IT”, where inevitably complications arise when outsourcing some IT services to the “cloud”.

As a result, we will find a way to collect information about our environment, including ways to resolve incidents, which will allow us to save time in the future if we have similar questions again. In addition to this, this information will allow management to make better decisions regarding the choice of future technologies and investments.

We will try to do this in such a way as not to force the organization to sell part of its employees to the authorities, and also does not require half of its life for implementation. Of course, this will require some creativity, including the search for outsourcing solutions. The idea of outsourced monitoring for internal systems is relatively new, and we will see how it applies.

I have to emphasize that most of what we look at will help to cope with the support of those managerial frameworks that many organizations are implementing today, including ITIL, which has become popular in recent years. You do not need to be an ITIL expert to take advantage of the new processes and techniques that I propose — you don’t even have to think about implementing ITIL (or any other framework) at all, unless your organization already does this. But if you already use a set of organizational procedures, you will be pleased to know that everything that is offered in this book will fit perfectly into them.

Conclusion

This chapter lists the four main topics that the remaining chapters of this book will cover. And their basis is that many experts consider the most serious and fundamental problems that IT has to face today, and also contain a number of things, on ways to correct which, we will concentrate in the rest. We will pay attention to changing the management philosophy and practices used, not only through the selection of new tools, although new tools may be the very basis you choose to implement these new solutions.

Chapter 2 will be devoted to the first problem practice, which is to manage the IT infrastructure for individual sites. We will look at the technological reasons why organizations are more or less forced to follow this path, and explore the directions from which you can begin to change the current practice.

In Chapter 3, we will discuss related people: IT managers, your users, your service desk, and so on. Only the general involvement of all employees in the process can allow IT to better adapt to the needs of the organization.

Our third problematic practice will be the subject of discussion for Chapter 4, where we dive into the search for externaldata center for monitoring. The final goal will be to solve the problems that we will discuss in this chapter, focusing further on the value created by IT for its organization.

Chapter 5 will look at ways to turn problems into solutions. Although modern organizations are fully aware of the need to track information passing through the helpdesk and build a knowledge system, the ways in which these processes are managed, being part of the overall IT management system, can represent a big difference compared to the originally planned value added.

The final conclusions will be made in Chapter 6, where we will attempt to visualize the IT environment that uses new, unified management practices. I will also give a number of stories that will help you see how these updated practices work in real life.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/173537/

All Articles