Theory of Relativity in Pictures

In my article I would like to talk about the theory of relativity. This theory is not required in the presentation. Since its creation, it has been shrouded in a halo of mystery, since it completely undermines our usual notions of space and time. We all at school taught the formulas of the theory of relativity, but few really understood them. And this is not surprising, because a person in order to truly understand a theory in all its beauty, completeness and consistency, it is not enough to know the formulas. You need to have some kind of visual reference point, you need a dynamic so that there is something that can be turned in your hands. I decided to fill this gap and wrote a small program in which you can “turn in your hands” space-time. We, as real researchers, will try to find out the main properties of this mysterious matter with the help of small experiments.

There are a lot of pictures under the cut (and not a single formula).

It should immediately be clear that there are two theories of relativity:

- the special theory of relativity (STR) considers the mechanics of motion of bodies in empty (not curved) space-time.

- The General Theory of Relativity (GTR) studies the phenomena of gravity and the curvature of space-time by objects possessing mass.

Everything described below refers to the first one.

Before considering space-time, let's remember what ordinary Euclidean space is.

And so, we have a plane. In this plane there are some geometric shapes: points, segments. We also have two operations: parallel transfer , and rotation . Let's take a closer look at these two operations.

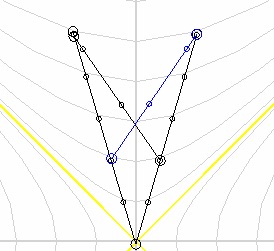

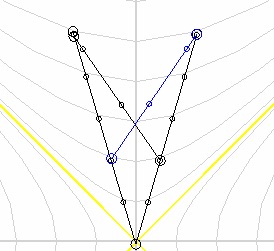

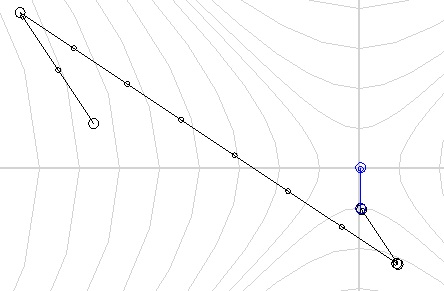

Next, we turn to the consideration of the so-called Minkowski space. In it, we left a parallel transfer, but the rotation operation was replaced by another operation. As you can see, during the "rotation" each point moves along gray curves. As a result, all points are drawn either along one yellow straight line or along the other.

With this “rotation”, the segments retain their shape and turn into segments.

Actually, this is space-time. Let's assume that the horizontal axis is space, and the vertical axis is time. We assume that the time comes from the bottom up. A point in space-time is some event that happened in a certain place at some time. A segment is a process. For example, if an object moves, then we will designate its movement as a segment.

So that you are a little oriented, we will put the first experiment.

')

First, we will consider objects moving at low speeds (much less than the speed of light).

Suppose there is some fixed object, for example a tree. Draw it using a vertical line.

We also have some moving object - a car. We see the car going towards the tree.

Draw another moving object. The result is a picture:

Note that the greater the slope, the greater the speed of the object.

This is our picture from a fixed frame of reference. And what will we see if we sit in the car? To do this, we need to slightly "skew" our plane.

All right The car is now immobile, and the tree and man are moving towards us.

Similarly, we can go to the frame of reference associated with a person. To do this, we need to “skew” the space-time in the other direction. In general, the process of transition from one reference system to another is as follows:

Such a transformation is called the “Galilean transformation”. In addition, each point moves along the horizontal line. This means that time is the same in all reference systems (time is absolute).

Let us now move to a larger scale, “squeezing” our X axis.

In fact, the transition from one frame of reference to another is nothing else but a “turn” in Minkowski space, and the Galilean transformations are just a limiting case for small speeds.

We see that the points are now not moving horizontally. Those. time is not an absolute value, but depends on the chosen reference system .

Suppose there are two observers, one motionless, the other flying in his spacecraft from him with some speed.

The marks on the segment show how time goes on inside the object. We see that the time of a stationary observer moves faster than that of a mobile (one hour for a moving observer comes later than that of a stationary).

But the second observer sees exactly the same picture.

This is how one frame goes to another

It turns out a strange situation - two observers are looking at each other, and they seem to each other to be "inhibited."

To find out which of them is actually a “brake”, the second observer turns his spaceship around and flies back.

Together, they check their clocks and find out that 5 time units of a stationary observer have passed, and a little more than 4 units of a mobile one. That is, an observer who “made a detour” in space-time spent less of his internal time than a fixed observer.

But the same thing, just exactly the opposite, would have happened if the first observer flew to the second to meet.

Conclusion: for a fixed observer, time always goes faster than for a moving one .

Suppose we have a fixed space station. From her undock some ship.

Let's go to the reference system of this ship. Then another ship undocked from this ship.

Then from the second ship undocked the third.

and so on.

So I tried to portray the acceleration process. Obviously, each next ship will move with greater speed than the previous one. Let's now go back to the first ship and see.

Let me remind you that the slope determines the speed. The yellow line, or rather its slope, shows the speed of light.

The image shows that each ship approaches the speed of light, but cannot exceed it. It is also seen that the internal time with increasing speed slows down more and more. From this we conclude that nothing can move at a speed exceeding the speed of light .

Let every ship now let out a ray of light.

We see that the light in any reference system moves at the speed of light .

Two yellow lines outline a figure called the "light cone." The light cone divides spacetime into two areas, which I have marked in red and green.

If an event is in the red region, then we will say that the event is within the light cone. This means that the light from the origin has time to reach our point.

If the event is in the green area, then we say that the event is outside the light cone, and the light from the origin does not have time to fly to this event.

Consider the following example. There are three simultaneous events.

Let's see what happens if we change the reference system.

We see that in a different frame of reference events are not at all simultaneous. Now events do not just shift in time, they also change their chronological order. An event that occurred before a certain event may occur later in another frame of reference. But how can this be? Is this a violation of cause and effect?

Let me remind you that if an event is outside the light cone, this means that the light cannot reach this event in the allotted time. And since nothing (no object or signal) can move faster than the speed of light, it turns out that an event that occurred at point A cannot affect the event at point B.

The same is true in the opposite direction. The event at point B cannot affect the event at point A.

They say that such events are not related by cause-effect relationships. It turns out that an event that is beyond the limit of the light cone relative to this one is not connected with it by cause-effect relationships .

All space objects: solar systems, galaxies - are at gigantic distances from each other. And even moving at the speed of light, it will take us a very long time to overcome these distances. For example, the nearest star (alpha-Centauri) is at a distance of 4 light years, and the nearest galaxy (Large Magellanic Cloud) is already 160 thousand light years. If before the alpha Centauri we can still fly "there and back", then fly "back and forth" in the neighboring galaxy will not work. More precisely, we will be able to fly away, but when we return, 320 thousand years will pass on the Earth (I remind you that time is almost at a standstill inside an object moving at the speed of light). What to do?

Science-fiction writers in their works very cleverly bypass this restriction. Something they didn’t make up: super-fast engines, hyper-spaces, multiplexes, space-time warping, wormhole jumping, black holes, etc. In fact, the problem is much deeper than it might seem. It lies in the fact that outside the light cone CANNOT exist cause and effect relationships. Otherwise, we will inevitably come to contradictions.

Consider an example. We are sitting on our planet. At one point, our scientists invent a “super teleporter” capable of teleporting us to any distance in the minimum amount of time. Well, we took and teleported to a nearby galaxy. After sitting in another galaxy, we went to further exploration of space.

If we now move to the reference system associated with our ship, we will see the following.

We see that our starting point (planet Earth) has shifted into the future. And since the laws of nature in all reference systems work in the same way, we can again use our “super teleporter” and return to our own past.

It turns out that the movement with super-light speed, is equivalent to moving in time, but it pulls a lot of paradoxes behind it. Thus, the problem of space travel is not that we are not able to bend space-time or build ultra-light engines, but the fact that even the theoretical possibility of such movements undermines all causal relationships.

On this, in general, that's all. The most basic seems to be told. I hope it was clear.

When writing an article, a program was used (Link to github )

There are a lot of pictures under the cut (and not a single formula).

It should immediately be clear that there are two theories of relativity:

- the special theory of relativity (STR) considers the mechanics of motion of bodies in empty (not curved) space-time.

- The General Theory of Relativity (GTR) studies the phenomena of gravity and the curvature of space-time by objects possessing mass.

Everything described below refers to the first one.

Euclidean space and Minkowski space

Before considering space-time, let's remember what ordinary Euclidean space is.

And so, we have a plane. In this plane there are some geometric shapes: points, segments. We also have two operations: parallel transfer , and rotation . Let's take a closer look at these two operations.

Next, we turn to the consideration of the so-called Minkowski space. In it, we left a parallel transfer, but the rotation operation was replaced by another operation. As you can see, during the "rotation" each point moves along gray curves. As a result, all points are drawn either along one yellow straight line or along the other.

With this “rotation”, the segments retain their shape and turn into segments.

Actually, this is space-time. Let's assume that the horizontal axis is space, and the vertical axis is time. We assume that the time comes from the bottom up. A point in space-time is some event that happened in a certain place at some time. A segment is a process. For example, if an object moves, then we will designate its movement as a segment.

So that you are a little oriented, we will put the first experiment.

')

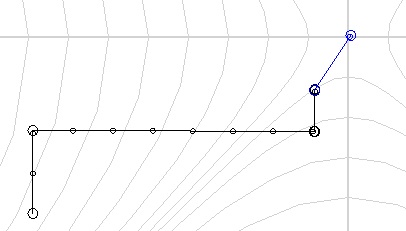

Experiment 1. Newtonian mechanics.

First, we will consider objects moving at low speeds (much less than the speed of light).

Suppose there is some fixed object, for example a tree. Draw it using a vertical line.

We also have some moving object - a car. We see the car going towards the tree.

Draw another moving object. The result is a picture:

Note that the greater the slope, the greater the speed of the object.

This is our picture from a fixed frame of reference. And what will we see if we sit in the car? To do this, we need to slightly "skew" our plane.

All right The car is now immobile, and the tree and man are moving towards us.

Similarly, we can go to the frame of reference associated with a person. To do this, we need to “skew” the space-time in the other direction. In general, the process of transition from one reference system to another is as follows:

Such a transformation is called the “Galilean transformation”. In addition, each point moves along the horizontal line. This means that time is the same in all reference systems (time is absolute).

Let us now move to a larger scale, “squeezing” our X axis.

In fact, the transition from one frame of reference to another is nothing else but a “turn” in Minkowski space, and the Galilean transformations are just a limiting case for small speeds.

We see that the points are now not moving horizontally. Those. time is not an absolute value, but depends on the chosen reference system .

Experiment 2. Slowing down time.

Suppose there are two observers, one motionless, the other flying in his spacecraft from him with some speed.

The marks on the segment show how time goes on inside the object. We see that the time of a stationary observer moves faster than that of a mobile (one hour for a moving observer comes later than that of a stationary).

But the second observer sees exactly the same picture.

This is how one frame goes to another

It turns out a strange situation - two observers are looking at each other, and they seem to each other to be "inhibited."

To find out which of them is actually a “brake”, the second observer turns his spaceship around and flies back.

Together, they check their clocks and find out that 5 time units of a stationary observer have passed, and a little more than 4 units of a mobile one. That is, an observer who “made a detour” in space-time spent less of his internal time than a fixed observer.

But the same thing, just exactly the opposite, would have happened if the first observer flew to the second to meet.

Conclusion: for a fixed observer, time always goes faster than for a moving one .

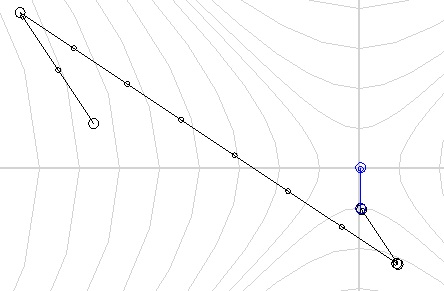

Experiment 3. The speed of light.

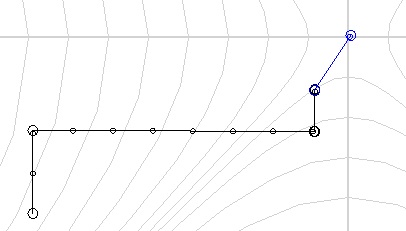

Suppose we have a fixed space station. From her undock some ship.

Let's go to the reference system of this ship. Then another ship undocked from this ship.

Then from the second ship undocked the third.

and so on.

So I tried to portray the acceleration process. Obviously, each next ship will move with greater speed than the previous one. Let's now go back to the first ship and see.

Let me remind you that the slope determines the speed. The yellow line, or rather its slope, shows the speed of light.

The image shows that each ship approaches the speed of light, but cannot exceed it. It is also seen that the internal time with increasing speed slows down more and more. From this we conclude that nothing can move at a speed exceeding the speed of light .

Let every ship now let out a ray of light.

We see that the light in any reference system moves at the speed of light .

Experiment 4. Light cone.

Two yellow lines outline a figure called the "light cone." The light cone divides spacetime into two areas, which I have marked in red and green.

If an event is in the red region, then we will say that the event is within the light cone. This means that the light from the origin has time to reach our point.

If the event is in the green area, then we say that the event is outside the light cone, and the light from the origin does not have time to fly to this event.

Consider the following example. There are three simultaneous events.

Let's see what happens if we change the reference system.

We see that in a different frame of reference events are not at all simultaneous. Now events do not just shift in time, they also change their chronological order. An event that occurred before a certain event may occur later in another frame of reference. But how can this be? Is this a violation of cause and effect?

Let me remind you that if an event is outside the light cone, this means that the light cannot reach this event in the allotted time. And since nothing (no object or signal) can move faster than the speed of light, it turns out that an event that occurred at point A cannot affect the event at point B.

The same is true in the opposite direction. The event at point B cannot affect the event at point A.

They say that such events are not related by cause-effect relationships. It turns out that an event that is beyond the limit of the light cone relative to this one is not connected with it by cause-effect relationships .

Experiment 5. Movement with super-light speed.

All space objects: solar systems, galaxies - are at gigantic distances from each other. And even moving at the speed of light, it will take us a very long time to overcome these distances. For example, the nearest star (alpha-Centauri) is at a distance of 4 light years, and the nearest galaxy (Large Magellanic Cloud) is already 160 thousand light years. If before the alpha Centauri we can still fly "there and back", then fly "back and forth" in the neighboring galaxy will not work. More precisely, we will be able to fly away, but when we return, 320 thousand years will pass on the Earth (I remind you that time is almost at a standstill inside an object moving at the speed of light). What to do?

Science-fiction writers in their works very cleverly bypass this restriction. Something they didn’t make up: super-fast engines, hyper-spaces, multiplexes, space-time warping, wormhole jumping, black holes, etc. In fact, the problem is much deeper than it might seem. It lies in the fact that outside the light cone CANNOT exist cause and effect relationships. Otherwise, we will inevitably come to contradictions.

Consider an example. We are sitting on our planet. At one point, our scientists invent a “super teleporter” capable of teleporting us to any distance in the minimum amount of time. Well, we took and teleported to a nearby galaxy. After sitting in another galaxy, we went to further exploration of space.

If we now move to the reference system associated with our ship, we will see the following.

We see that our starting point (planet Earth) has shifted into the future. And since the laws of nature in all reference systems work in the same way, we can again use our “super teleporter” and return to our own past.

It turns out that the movement with super-light speed, is equivalent to moving in time, but it pulls a lot of paradoxes behind it. Thus, the problem of space travel is not that we are not able to bend space-time or build ultra-light engines, but the fact that even the theoretical possibility of such movements undermines all causal relationships.

Conclusion

On this, in general, that's all. The most basic seems to be told. I hope it was clear.

When writing an article, a program was used (Link to github )

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/169347/

All Articles