Efficient string concatenation in .NET

For programmers on the .NET platform, one of the first tips to improve the performance of their programs is “Use StringBuilder for string concatenation”. As well as “ Exception use is expensive ”, the statement about concatenation is often misunderstood and turns into dogma. Fortunately, it is not as destructive as the myth of the performance of exceptions, but it is much more common.

It would be nice if you read my previous article about .NET strings before reading this article. And, in the name of readability, I will continue to denote strings in .NET just as strings, and not “string” or “System.String”.

I included this article in the list of articles on the .NET Framework in general, and not in the list of C # -specific articles, since I believe that all the languages on the .NET platform under the hood contain the same string concatenation mechanism.

The problem that they are trying to solve

The problem of concatenating a large array of strings, in which the resulting string grows very quickly and strongly, is very real, and the advice to use StringBuilder for concatenation is very correct. Here is an example:

using System; public class Test { static void Main() { DateTime start = DateTime.Now; string x = ""; for (int i=0; i < 100000; i++) { x += "!"; } DateTime end = DateTime.Now; Console.WriteLine ("Time taken: {0}", end-start); } } On my relatively fast laptop, this program took about 10 seconds to complete. If you double the number of iterations, the execution time will increase to a minute. On .NET 2.0 beta 2, the results are slightly better, but not so much. The problem with poor performance is that rows are immutable (immutable), and therefore, when using the “

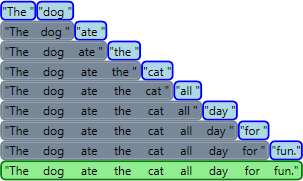

+= ” operator, the line is not added to the end of the first iteration at the next iteration. Actually, the expression x += "!"; is absolutely equivalent to the expression x = x+"!"; . Here concatenation is the creation of a completely new line for which the required amount of memory is allocated, into which the contents of the existing value of x are copied, and then the contents of the concatenated string ( "!" ) Are copied. As the resulting row grows, the amount of data that is copied back and forth all the time increases, and that is why when I doubled the number of iterations, the time grew more than doubled.')

This concatenation algorithm is definitely inefficient. After all, if someone asks you to add something to the shopping list, you will not copy the entire list before adding, right? This is how we approach StringBuilder.

Use StringBuilder

And here is the equivalent (equivalent in the sense of the identical final value

x ) of the above program, which is much, much faster: using System; using System.Text; public class Test { static void Main() { DateTime start = DateTime.Now; StringBuilder builder = new StringBuilder(); for (int i=0; i < 100000; i++) { builder.Append("!"); } string x = builder.ToString(); DateTime end = DateTime.Now; Console.WriteLine ("Time taken: {0}", end-start); } } On my laptop, this code runs so fast that the time metering mechanism that I use is inefficient and does not give satisfactory results. With an increase in the number of iterations to one million (i.e., 10 times more than the initial number, at which the first version of the program was executed in 10 seconds), the execution time increases to 30-40 million seconds. Moreover, the execution time grows approximately linearly with the number of iterations (i.e., having doubled the number of iterations, the execution time will also double). Such a jump in performance is achieved by eliminating the unnecessary copy operation — only the data that is attached to the result string is copied. StringBuilder contains and maintains its internal buffer and, when a string is added, copies its contents to the buffer. When new join lines do not fit into the buffer, it is copied with all its contents, but with a larger size. In essence, the internal StringBuilder buffer is the same regular string; strings are immutable only in terms of their public interfaces, but are modifiable by the

mscorlib assembly. It would be possible to make this code even more efficient by specifying the final size (length) of the string (after all, in this case we can calculate the size of the string before the beginning of the concatenation) in the StringBuilder constructor , so that the internal StringBuilder buffer would be created with exactly the resulting string is in size, and during the concatenation process it would not be able to grow through copying. In this situation, you can determine the length of the resulting string before concatenation, but even if you cannot, it does not matter - when filling the buffer and copying it, StringBuilder doubles the size of the new copy, so there will not be too many fillings and copies of the buffer.So with concatenation, should I always use StringBuilder?

In short - no. All of the above explains why the statement “Use StringBuilder for string concatenation” is correct in some situations. At the same time, some people take this statement for dogma, without understanding the basics, and as a result, they begin to alter such code:

string name = firstName + " " + lastName; Person person = new Person (name); Here in this:

// Bad code! Do not use! StringBuilder builder = new StringBuilder(); builder.Append (firstName); builder.Append (" "); builder.Append (lastName); string name = builder.ToString(); Person person = new Person (name); And all this in the name of performance. If you look at the problem in general, even if the second version would be faster than the first version, then obviously it would not be much faster , because there are only a few concatenations. The meaning of using the second version can be only if this piece of code is called a very, very large number of times. The deterioration of the readability of the code (and I think you will all agree that the second version is much less readable than the first) for the sake of a microscopic increase in performance is a very bad idea.

Moreover, in fact, the second version, with StringBuilder, is less productive than the first version, although not by much. And if the second version were more easily perceived than the first, then after the argument from the previous paragraph, I would say - use it; but when the version with StringBuilder is less readable and less productive, then using it is just nonsense.

If we assume that firstName and lastName are “real” variables, not constants (this will be discussed later), then the first version will be compiled into a call to String.Concat , something like this:

string name = String.Concat (firstName, " ", lastName); Person person = new Person (name); The String.Concat method takes as input a set of strings (or objects) and “sticks together” them into one new line, simply and clearly. String.Concat has different overloads - some accept several strings, some - several variables of type

Object (which are converted to strings during concatenation), and some accept arrays of strings or Object arrays. All overloads do the same thing. Before the actual concatenation process begins, String.Concat reads the lengths of all the strings passed to it (at least if you passed strings to it - if you passed variables of type Object , then String.Concat will create a new temporary (intermediate) string for each such variable and concatenate already her). Thanks to this, at the time of the concatenation, String.Concat accurately "knows" the length of the resulting string, thereby allocating for it an exactly suitable buffer size, and therefore there are no unnecessary copy operations, etc.Compare this algorithm with the second StringBuilder version. At the time of its creation, StringBuilder does not know the size of the resulting string (and we didn’t “say” this size; and if they did, it would have made the code even less understandable), which means that, most likely, the size of the start buffer will be exceeded , and StringBuilder will have to increase it by creating a new one and copying the contents. Moreover, as we remember, StringBuilder doubles the buffer, which means that, in the end, the buffer will be much larger than the resulting string requires. In addition, we should not forget about the overhead associated with the creation of an additional object that is not in the first version (this object is StringBuilder). So why is the second version better?

An important difference between the example from this section and the example from the beginning of the article is that in this we immediately have all the strings that need to be concatenated, and therefore we can transfer all of them to String.Concat, which, in turn, will produce the result effectively, without any intermediate lines. In the earlier example, we do not have access to all strings at once, and therefore we need a temporary storage of intermediate results, the role of which is best suited for StringBuilder. That is, summarizing, StringBuilder is effective as a container with an intermediate result, as it allows to get rid of the internal copying of strings; if all strings are available immediately and there are no intermediate results, then StringBuilder will have no benefit.

Constants

The situation gets even worse when it comes to constants (I'm talking about string literals declared as

const string ). What do you think, what expression will be compiled string x = "hello" + " " + "there"; ? It is logical to assume that the call to String.Concat will be made, but it is not. In fact, this expression will be compiled into this: string x = "hello there"; . The compiler knows that all components of the string x are compile-time constants, and therefore all of them will be concatenated at the time of compiling the program, and the string x with the value "hello there" will be stored in the compiled code. Translation of such code under StringBuilder is inefficient both in terms of memory consumption and in terms of CPU resources, not to mention readability.Empirical rules of concatenation

So, when to use StringBuilder, and when is a “simple” concatenation?

- Definitely use StringBuilder when you are concatenating strings in a non-trivial loop, and especially when you do not know (at the time of compilation) how many iterations will be performed. For example, reading the contents of a text file by reading one character at a time in one iteration in a loop, and concatenating this character through the

+=operator presumably “kills” your application in terms of performance. - Definitely use the

+=operator if you can specify all the necessary string concatenation in a single statement. If you need to concatenate an array of strings, use an explicit call to String.Concat, and if you need a separator between these strings, use String.Join . - Do not be afraid to break literals into several parts in code and link them through

+- the result will be the same. If you have a long literal string in your code, then breaking it up into several substrings will improve the readability of the code. - If the intermediate results of the concatenation are needed by you somewhere else , besides actually being intermediate results (ie, serve as a temporary storage of strings, changing at each iteration), then StringBuilder will not help you. For example, if you create a full name by concatenating a name and a surname, and then add a third element (for example, login) to the end of a string, then StringBuilder will be useful only if you do not need to use the string (first name + last name) by itself, without a login, somewhere else (as we did in the example, creating an instance of

Personbased on the name and surname). - If you need to concatenate multiple substrings, and you cannot concatenate them in one statement via String.Concat, then the choice of “classical” - or StringBuilder concatenation will not play a special role. Here, the speed will depend on the number of strings involved in the concatenation, on their length, and on the order in which the strings will be concatenated. If you believe that concatenation is a “bottleneck” of performance and you definitely want to use the fastest method, measure the performance of both methods and only then select the fastest one.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/166701/

All Articles