How a programmer became a product manager

Jim Gochee, New Relic Inc.

September 11, 2012

translation of A Developer Becomes a Product Manager

In the good old days, I earned my living by programming. It was one of the best and carefree stages in my working life. In addition to writing code, I had few other responsibilities. I had no idea where the company took the money for my salary and could not imagine where customers would learn about our product. I did not think about why my boss asks me to program the X / Y / Z features — I just wrote code. My time was occupied with solving interesting technical problems and, in general, my life revolved around programming.

')

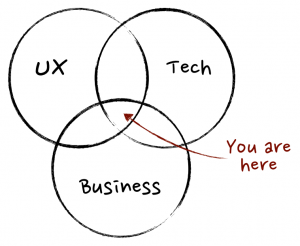

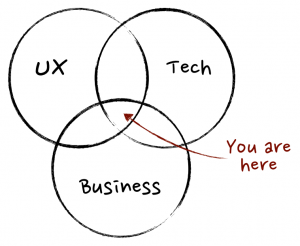

Time passed and I began to notice that outside of my engineering team there is a whole other world - the world of “business”, or as I call it now - the “real” world. In this world, investments are attracted, products are advertised and sold, customers are served, and salaries are reduced. All the time that product managers

spend not with engineering teams, they spend in this real world. In technology startups, the role of product manager is often played by the CEO. In large companies, product managers are mini-CEOs. (If you want to know more about the impact of product managers, read the article on Marissa Meyer , which discusses the role of product managers in Google.)

The task of the product manager is to ensure that the work of the engineering team goes in the direction coinciding with the business goals of the company. One of the obvious goals is to create a product that the sales department can sell, in which the marketing department can interest potential customers and which the technical support department can support. Less obvious goals include leveling competitive threats, strategic product positioning, satisfying investors' wishes, and creating long-term benefits for shareholders. And although these are fairly vague concepts, they help define the context for daily decision making by the product manager.

If I wanted to describe the daily life of a product manager in one word, it would be the word "NO." Once the product is launched, the number of ideas on how to improve it (aka “new features”) will significantly exceed the capabilities of your team in their implementation. At NewRelic, we've been tracking improvement requests for two years. When their number reached 1000, we stopped, scratched our heads and removed them all. We stopped tracking new requests individually and just began to count them. In such a situation, the product manager can focus on a small number of cases that will bring the greatest return in the business, and say no to all other requests. (One simple way to achieve this is to keep a prioritized list of future work.) And when those unavoidable two or three requests come in a day, they can be compared with the list of top-10 and they will either fall into this list (and force out something else) either will not fall.

Business objectives may differ in different companies, but it is usually common for all projects that they have to create a product for “someone” who does “something”. This someone is called the fashion term "Person". Sometimes there is only one person in the product, sometimes a couple. And it is very important to understand who these people are. How can you build something for someone if you don’t even understand them? Programmers often step on this rake and believe that they create a product for someone like themselves. (Well, after all, our users also use computers, right?). Take for example Salesforce - these guys understand exactly who the Persons are for their product: sales representatives, sales managers and top management.

“Something” is important because your product is most likely designed to solve a certain number of “problems” or “pain points”. For example, if your product is a Performance Monitoring Solution, it is important that your customers solve your application's performance problems with your product. The second most frequently used expression (after “NO”) by me is “what problems does it solve?”. Here is an example of a real situation that you may have to face. Designers do not like the layout of the web page and they insist on changing it. This change will make the product better, so there shouldn't be any problems, right? But the danger may lie in two places: a) users do not experience problems with the existing layout b) users experience other design problems - and as a result, the solution of these problems will be delayed.

If you ask yourself - which of the problems in my product are the most acute and direct the team to solve exactly these problems, then this will be the correct prioritization of backlog. And the last remark about “problems” - sometimes they are disguised as other things, such as “opportunities”. For example, users will not tell you that installing an application takes too much time. There is no obvious problem here. However, as a smart person, you will be able to recognize that speeding up the installation process will increase the number of sales. Long application installation time is a problem because users have a short attention span. Another example is the Apple iPod. The iPod did not bring new functionality to the market, but it was simple and stylish - a fashionable product. The fashion factor at first glance does not solve any problem, people just want to be fashionable. But by offering a fashionable product on the market, one can satisfy the desire (to solve the problem) of a large group of people.

And although I sometimes miss programming, I'm not ready to exchange product management for it. I like to play a key role in the success of NewRelic, and I like how successful NewRelic is!

September 11, 2012

translation of A Developer Becomes a Product Manager

In the good old days, I earned my living by programming. It was one of the best and carefree stages in my working life. In addition to writing code, I had few other responsibilities. I had no idea where the company took the money for my salary and could not imagine where customers would learn about our product. I did not think about why my boss asks me to program the X / Y / Z features — I just wrote code. My time was occupied with solving interesting technical problems and, in general, my life revolved around programming.

Real world

')

Time passed and I began to notice that outside of my engineering team there is a whole other world - the world of “business”, or as I call it now - the “real” world. In this world, investments are attracted, products are advertised and sold, customers are served, and salaries are reduced. All the time that product managers

spend not with engineering teams, they spend in this real world. In technology startups, the role of product manager is often played by the CEO. In large companies, product managers are mini-CEOs. (If you want to know more about the impact of product managers, read the article on Marissa Meyer , which discusses the role of product managers in Google.)

The task of the product manager is to ensure that the work of the engineering team goes in the direction coinciding with the business goals of the company. One of the obvious goals is to create a product that the sales department can sell, in which the marketing department can interest potential customers and which the technical support department can support. Less obvious goals include leveling competitive threats, strategic product positioning, satisfying investors' wishes, and creating long-term benefits for shareholders. And although these are fairly vague concepts, they help define the context for daily decision making by the product manager.

If I wanted to describe the daily life of a product manager in one word, it would be the word "NO." Once the product is launched, the number of ideas on how to improve it (aka “new features”) will significantly exceed the capabilities of your team in their implementation. At NewRelic, we've been tracking improvement requests for two years. When their number reached 1000, we stopped, scratched our heads and removed them all. We stopped tracking new requests individually and just began to count them. In such a situation, the product manager can focus on a small number of cases that will bring the greatest return in the business, and say no to all other requests. (One simple way to achieve this is to keep a prioritized list of future work.) And when those unavoidable two or three requests come in a day, they can be compared with the list of top-10 and they will either fall into this list (and force out something else) either will not fall.

Defining goals

Business objectives may differ in different companies, but it is usually common for all projects that they have to create a product for “someone” who does “something”. This someone is called the fashion term "Person". Sometimes there is only one person in the product, sometimes a couple. And it is very important to understand who these people are. How can you build something for someone if you don’t even understand them? Programmers often step on this rake and believe that they create a product for someone like themselves. (Well, after all, our users also use computers, right?). Take for example Salesforce - these guys understand exactly who the Persons are for their product: sales representatives, sales managers and top management.

“Something” is important because your product is most likely designed to solve a certain number of “problems” or “pain points”. For example, if your product is a Performance Monitoring Solution, it is important that your customers solve your application's performance problems with your product. The second most frequently used expression (after “NO”) by me is “what problems does it solve?”. Here is an example of a real situation that you may have to face. Designers do not like the layout of the web page and they insist on changing it. This change will make the product better, so there shouldn't be any problems, right? But the danger may lie in two places: a) users do not experience problems with the existing layout b) users experience other design problems - and as a result, the solution of these problems will be delayed.

If you ask yourself - which of the problems in my product are the most acute and direct the team to solve exactly these problems, then this will be the correct prioritization of backlog. And the last remark about “problems” - sometimes they are disguised as other things, such as “opportunities”. For example, users will not tell you that installing an application takes too much time. There is no obvious problem here. However, as a smart person, you will be able to recognize that speeding up the installation process will increase the number of sales. Long application installation time is a problem because users have a short attention span. Another example is the Apple iPod. The iPod did not bring new functionality to the market, but it was simple and stylish - a fashionable product. The fashion factor at first glance does not solve any problem, people just want to be fashionable. But by offering a fashionable product on the market, one can satisfy the desire (to solve the problem) of a large group of people.

And although I sometimes miss programming, I'm not ready to exchange product management for it. I like to play a key role in the success of NewRelic, and I like how successful NewRelic is!

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/161421/

All Articles